How to become a woman, without being cut

Many FGM traditions are rooted in a transition to womanhood. Maasai girls in Kenya are continuing rich, coming-of-age rituals – without genital mutilation – and learning about their bodies instead.

Many FGM traditions are rooted in a transition to womanhood. Maasai girls in Kenya are continuing rich, coming-of-age rituals – without genital mutilation – and learning about their bodies instead.

On the way to becoming a woman

The transformation to womanhood for these Maasai girls in Kajiado, Kenya, used to happen in a three day ritual, during which girls were also cut. Today, that ceremony still exists: all the rites and celebrations, songs and dances still take place – without the cutting.

Instead of silence, education

With cutting, women endured a horrific rite of passage and suffered in silence. Now, the three-day ritual is about open communication and education. They get training on sexual and and reproductive rights while their mothers cook and care for them.

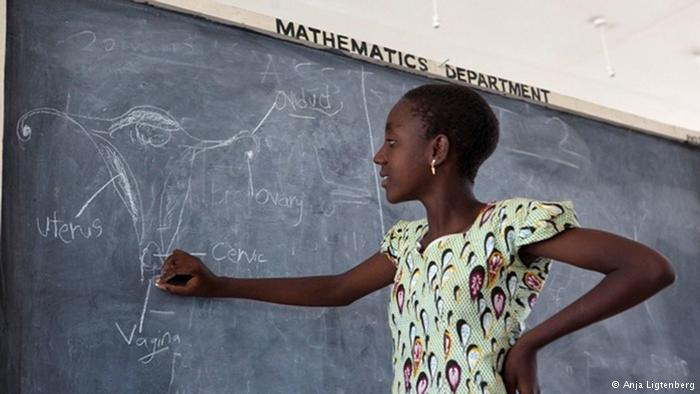

Learning about bodies

This new rite of passage involves teaching girls about how the female body looks and works. This basic information – including conversations about FGM – is key in fighting against the continuation of the practice. The workshops are sponsored by NGOs like Amref Health Africa.

A girl’s get-together

Beyond the educational part, girls prepare performances for their community. In the night before the actual rite of passage, the girls gather in a so-called “candle night”, where they perform their dances and songs the first time.

The role of men

The young Maasai men who might become the community leaders – known as Morans – gather before the cultural events start. The men play a crucial role accepting the alternative rite of passage.

The freedom to choose

Nice Lengete was the first one not being cut. Instead, Nice learned in a workshop about sexual health rights and today, she educates the women in her village. To do so, she sought support from village elders. “And amazingly they listened. To me – Nice!” she said. “I helped [them] understand the need for using condoms, going for treatment for sexually transmitted infections and taking HIV tests.”

Different colors, different meanings

For the rite of passage, the girls dress up for the celebrations: they wear special necklaces and clothes. Depending on the Maasai community, the colors have symbolism behind them, from bravery to sustenance to fertility.

Protecting girls from bad omens

Each community has special rites that form the cultural part of the three-day retreat. Women may shave their heads or have their faces painted. The paintings are meant to protect the girls from bad omens.

Creating individual rituals

Preserving long-held cultural rituals in the new alternative rite of passage is crucial to acceptance by village elders. In one community, a ritual that involves pouring a mix of milk and water over the girl’s head was maintained. Each community creates their own customs, gives them meaning and adapts it to new circumstances if necessary.

The final day

On the final day, there are speeches and dance performances. It’s all part of blessing the girls and moving from one part of life to another. As part of that, the women walk underneath sticks that other community members hold over their heads.

Mission accomplished

The alternative rite of passage ends with each girl being blessed and receiving a certificate of completion in the educational workshop. Since the introduction of the alternative rite of passage in 2009, more than 7,000 Maasai girls have taken part and been saved from cutting.

WTO RECOMMENDS

FGM: a tradition that remains alive despite international condemnation

Female genital mutilation is still practised in many African countries, despite being officially banned. Girl members of the semi nomadic Pokot ethnic group in Kenya have to undergo the painful ritual. (From February 24, 2015)

Spare the blade

The one-million-strong Bohra community in India is a small group of a muslim sect called the Ismaili Shias who are believed to have originated in Egypt. In India, they have settled in the western states of Gujarat, Maharashtra and Rajasthan. This group practices female genital mutilation (FGM). (From February 7, 2013)

Challenging tradition in Iraqi Kurdistan

A number of female journalists in Iraqi Kurdistan are shaking up a male-dominated domain with a magazine that aims to highlight the problems and abuse many women still face. (From April 9, 2015)