Combating Acid Violence: The Bangladesh model

© Prothom Alo Trust

Acid violence is prevalent in Bangladesh with perpetrators throwing acid at the faces and/or bodies of victims. Although these latter are predominantly young women, there have been acid attacks on older women, hildren and even men in recent years. These attacks frequently are the result of disputes involving money, land and dowries. They are often revenge for romantic rejection.

I have been reading about the recent acid attacks in Britain with great shock and surprise. I was always under the impression that acid violence occured only in developing countries , but this is apparently not the case. Some of the recent attacks in the UK are being treated as hate crimes. The victims have been both male and female. This is a different situation than what is usually the case in Bangladesh.

As the Chief Operations Officer of the Prothom Alo Trust, this is an issue I care very deeply about. For the past nine years, I have been working to rehabilitate victims of acid violence in Bangladesh. I have seen the burnt bodies of victims, their relatives waiting by their hospital beds, the ensuing lifelong struggles and bouts of depression. Some victims of acid attacks have the courage to fight back and get on with their lives; others never manage.

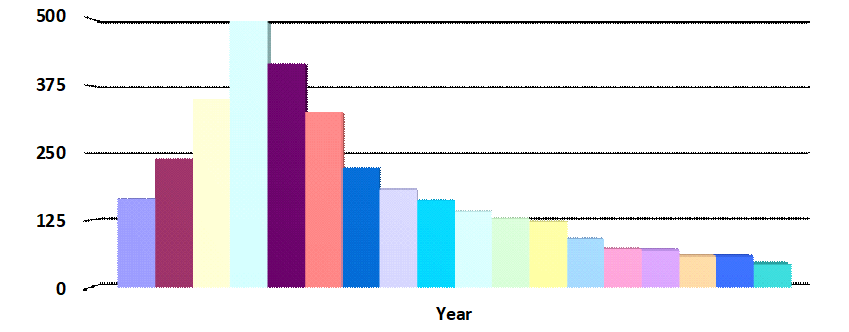

In 2002 , the number of acid attacks in Bangladesh reached a record high: 487. Last year, it had fallen to 44 after awareness-raising campaigns organized by the government and NGOs and highlighted in the media.

Before 2002, there was absolutely no provision in the legal framework to prevent acid violence or to justly punish the perpetrators. Acid violence related offenses were mainly dealt under the ‘Prevention of Oppression against Women and Children Act 2000’. Prothom Alo Trust, Acid Survivors Foundation, and other strategic partners in this campaign relentlessly presented their petition to the government to persuade them to initiate and implement new laws specifically crafted for acid offense. On March 17, 2002, The Acid Control Act of 2002 and The Acid Crime Control Act of 2002 were introduced by the government.

Acid Offense Control Act

The Acid Offense Prevention Act of 2002 is intended to control acid violence by penalty ranging between three and fifteen years; and depending on the severity of the case, life imprisonment to a maximum death sentence. The variations of punishment depend on the parts of the body affected.

The law clearly states that punishment for killing of a person by acid or injuring a person resulting in loss of vision, loss of hearing or disfigurement of the face, breasts or sexual organs can result in capital punishment, or rigorous imprisonment for life. Damage or disfigurement of body will result in fourteen years of imprisonment but not less than seven years of rigorous imprisonment. Punishment for attempt to throw acid causing no damage or injury may extend to seven years but not less than three years of rigorous imprisonment and also with a fine not exceeding fifty thousand taka. Also, if someone assists to commit the crime of acid throwing, he/she will receive the same punishment as the perpetrator.

© Prothom Alo Trust

The Acid Control Act of 2002 has been introduced to control “the import, production, transportation, hoarding, sale and use of acid, and to provide treatment to victims of acid violence, rehabilitate them, and provide legal assistance”. The act punishes the unlicensed production, import, transport, storage, sale and use of acid by a jail term of three to ten years and a fine of up to taka 50,000. It establishes the central government’s authority over import licenses and the deputy commissioner as the authority for transport, storage, seller and user licenses. The act also requires license holders to keep informational records relating to all acid use. The National Acid Control Council (NACC) and District Acid Control Committees (DACC) were established under this act.

National Acid Control Council (NACC) is mandated to develop policies and monitoring systems for the production, trade and deposit of acid and to develop medical, rehabilitation and legal support services for the victims of acid violence. Accordingly District Acid Control Committees (DACC) work to implement the decisions of NACC.

On July 17th this year, The Guardian reported: “On 13 July, five acid attacks occurred across north London in the space of ninety minutes, causing ‘life-changing’ injuries in at least one case, with others severely injured. Two of the alleged attackers have been arrested, yet little is known about them. This follows several incidents of acid violence in London, including an attack last month against Resham Khan and Jameel Muhktar.” This is highly alarming and demands immediate action from the UK government, which should The sale and distribution of acid on the UK market needs to be regulated more strictly as is now the case in Bangladesh. Bangladeshi law has become so effective that Pakistan and Cambodia have emulated it.

On July 17th, the BBC explained that perpetrators of acid attacks can already face life sentences. ” Home Secretary Amber Rudd told the Sunday Times she wanted them to ‘feel the full force of the law’. There are calls to tighten laws for the sale and possession of acid after five attacks on one night in London.” Bangladesh was able to reduce numbers by tightening the law.

The media can also play a vital role in awareness campaigns. The daily Prothom Alo (Bangladesh’s highest-circulated daily) makes a deliberate effort to highlight cases throughout the country. The Prothom Alo Trust Fund was established on April 19, 2000 with the slogan:“Let no more face burn in acid”. It runs awareness and rehabilitation campaigns and also publishes investigative reports into the supply chain of acid, follow-up news about victims and information as to what to do in the event of an acid attack. In 2005, the editorof Prothom Alo, Matiur Rahman, who is also the managing trustee of the trust board, won the prestigious Ramon Magseysey Award for Prothom Alo’s work combating acid violence.

Prothom Alo Trust has rehabilitated 456 women and girls across the country. We have given them shelter, shops, trawlers, rickshaws, sewing machines and farm animals to enable them to be financially independent. We have organized various discussion forums, seminars and human chains in areas where acid violence is particularly prevalent.

The Prothom Alo Trust also organizes seminars, rallies and round table discussions with other NGOs such as the Acid Survivors Foundation.

It is their efforts that compelled the government to act and the business community to get involved and finance initiatives. Journalists, celebrities, writers, sportsmen and women are all fighting this war together. Our aim is to eliminate acid violence from Bangladesh.

Author: Aziza Ahmed

Editor: Anne Thomas

_____

WTO RECOMMEND

Acid Attack – A Cowardly Move by Male Chauvinists

Women are victims of 80% of the roughly 1,500 acid attacks reported globally each year, says London-based charity Acid Survivors Trust International. These cowardly moves are meant to maim, disfigure or blind the victims. It is an atrocious act to cause shame, pain and suffering for other people. (From June 12, 2015)

Acid attacks: when love turns into hate

Acid attacks in several Asian countries like India, Pakistan, Bangladesh and Afghanistan have been plaguing women for a very long time. In fact, even men have sometimes fallen prey to obsessed lovers who use this method to take revenge. Here is a repost of an older Women Talk Online report in which an acid attack survivor, Sonali Mukherjee, spoke to Samrah Fatima about her experiences.That one night turned my life upside down! My body got seventy percent burnt. I could neither see nor hear nor talk. All that could mark me alive was my breath. I kept wondering why I not die that night, and today I have the answer. (From October 13, 2014)

Acid attacks: a tool to threaten women

Women in Pakistan’s troubled province Baluchistan are fearful after a spate of attacks that targeted women going out without male family members. A couple of days before Eid (the Islamic festival marking the end of Ramadan), two men on a motorcycle sprayed acid-filled syringes on two teenage girls who were returning from the market in Mastung, a district in Pakistan’s troubled province Baluchistan. The day before, four women aged between 18 and 50 also suffered the same fate in Quetta city when they were in the market area. Fortunately, these women were only partially burned. (From August 20, 2014)