The tale of a living deity

Her hair is tied up in a top knot. Thick kohl lines her eyes up to the temples. Her forehead is painted in red, with a silver agni chakchuu – the third eye, which is known as the fire eye – staring out from the center. She sits playfully on her mother’s lap while one by one people kneel down to offer her flowers, donations or simply to touch her feet. She appears shy to me, as if not used to receiving strangers. Despite the shyness, her eyes sparkle with curiosity.

Trishna Shakya is barely three years old. She is a Kumari – a living, breathing deity. She is worshipped by both Hindus and Buddhists in Nepal, who believe her to be the reincarnation of goddess Durga. ‘Kumari’, which comes from the Sanskrit word ‘Kaumarya’ or ‘virgin’, is the tradition of worshipping pre-pubescent girls as manifestations of divine female energy. Largely unknown to the outside world, this tradition that dates back to the 17th century continues to make Nepal unique. The power of Kumari is perceived to be so strong that even a glimpse of her will bring great fortune. Crowds of people wait below the window of her residence, hoping that she will glance down at them.

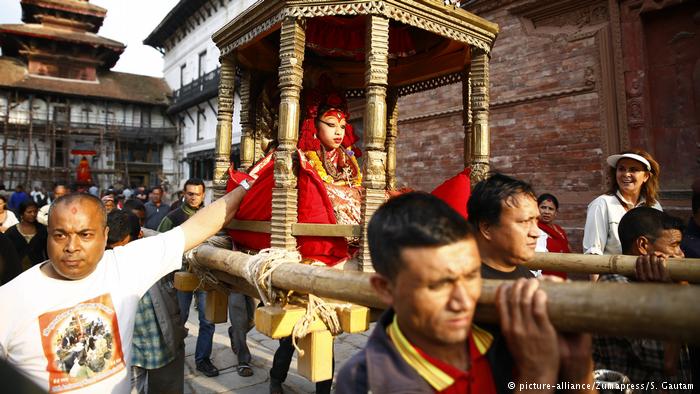

Living Goddess Kumari is carried in a palanquin by devotees along the streets during the Seto Machindranath chariot festival at Hanuman Dhoka Durbar Square in Kathmandu, Nepal on Tuesday, April 04, 2017

The selection of Kumari is an elaborate affair. To be chosen as a Kumari, a young girl must meet specific standards: She must be aged between three and seven and belong to the Shakya community. Moreover, she must possess 32 very specific physical attributes, known as the battis lakshanas, such as an “unblemished body”, a “chest like a lion” and “thighs like a deer”. She must also be “fearless” and “serene”.

Once chosen, the Kumari has various ceremonial duties to perform. She has to lead a very careful life for it is believed that any amount of bad luck could turn her into mortal. A minor cut or bleeding could render her invalid for worship, for instance. Her feet are never supposed to touch the ground so she is always carried. A Kumari is allowed to leave her residence only on special holy occasions. Her family is allowed to visit her only rarely and only in a formal capacity.

While there are several Kumaris in Nepal, the best known is the Royal Kumari of Kathmandu, who lives in the Kumari ghar, a palace in the center of the Nepalese capital.

A Kumari’s godhood comes to an end with her first menstruation, as the goddess is believed to have vacated her body. Thus, the search for a new Kumari begins. Along with the challenge of having to return to the normal life after their reign, another hurdle former Kumaris face is an old Nepali superstition that says men who marry ex-Kumaris will die a premature death.

A devotee offers prayers to Nepal’s newly appointed Living Goddess Kumari, Trishna Shakya, at her home before she formally takes her Kumari House in Kathmandu, Nepal, Sept. 28, 2017.

Some activists have criticized the Kumari tradition as child labor. But in 2008, Nepal’s Supreme Court overruled a petition to end the practice, citing its cultural value.

The main Kumari puja festival takes place during September or October and the living goddess in all her bejeweled splendor is borne in a palanquin and paraded across the city. The Ghode Jatra festival, the Sweta Machhendranath festival, the Rato Machhendranath festival and the Indra Jatra festival are other grand carnivals where devotees can witness the chariot procession of the Kumari and seek her blessings.

The extraordinary childhood of a Kumari can appear to be surreal and strange, but according to those who have lived to tell the tale, it is a privilege and many former Kumaris consider it a sacred duty and honor to perpetuate the ancient tradition and protect the culture.

Author: Preeti Shakya

Editor: Anne Thomas

___

WTO RECOMMENDS

Devadasi – Servants of God, used and discarded afterwards

It is an ancient religious practice that still traps young girls in India in a life of sexual exploitation. In India, devadasi means “servant of god.” Young girls are “married” to an idol, deity, or temple. These girls are often from the lowest castes in India—their parents have given them to temples as human offerings in order to appease the gods.

“The biggest case of social injustice till today is one that is faced by widows”

DURGA, a photography project by Sharmistha Dutta that addresses the apathy and gender inequality that exists against women, especially widows in India. WTO Reporter Roma Rajpal Weiß spoke to her on the plight of widows in India and the inspiration behind her project.

The Monthly Exiles

Five days ago, Sita Karki, 14, was forced into isolation in a filthy, dark and sweltering cattle shed about 10 minutes away from her home. The reason is that she is menstruating. Sita is one of thousands of girls and women in rural Nepal who every month are banished from their homes for five to eight days as part of a customary practice known as ‘Chhaupadi pratha‘. (Chhaupadi combines the words ‘chhau’ which translates as “untouchable” and ‘padi’ which means “being”.) The custom comes from a superstitious belief that during menstruation women are “impure” and “untouchable” and that her family with be visited by death and destruction if the taboo is broken because the gods will be angered.