Oswald Oelz: “Mountaineers are unteachable”

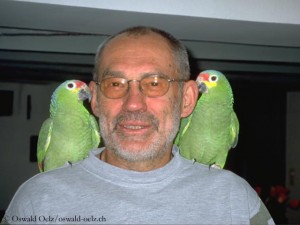

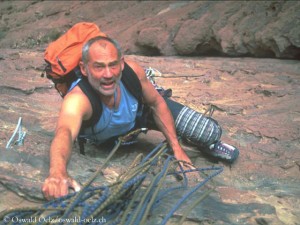

“I will climb until I am dead,” says Oswald Oelz, sitting opposite me recently at the International Mountain Summit in Bressanone. The 73-year-old native of Austria lives as a retiree in an old farmhouse in the Zurich Oberland region in Switzerland. “I have a farm with sheep, parrots, ducks, geese, chickens. I write, read a lot, climb. And I travel around the world.” Oswald called “Bulle” Oelz scaled Mount Everest in 1978, on the same expedition, during which Reinhold Messner and Peter Habeler climbed the highest mountain on earth for the first time without bottled oxygen. Oelz succeeded first ascents in the Alps, in Alaska, Jordan and Oman. Until 2006 he worked as chief physician at the “Triemli hospital” in Zurich. The professor also researched in the field of high altitude medicine.

Oswald Oelz, you are a mountaineer and a doctor, you have got to know both worlds. Time and again, there are fatalities in the high mountains due to high altitude cerebral or pulmonary edema. Has the climbing community learned nothing over the past decades?

The climbing community has learned nothing insofar as they still climb up to altitudes where a human being doesn’t really belong. Above 5,300 meters, man is not able to survive in the long run. Nevertheless, he goes up there. This is a charm, a thrill. If he is sufficiently acclimatized, he can stay up there for a shorter or longer time. The problem is that, on the one hand, people are willing to ascent who are less fit for high altitude and, on the other hand, they climb too fast too high. The typical example is Kilimanjaro, where you climb up to almost 6,000 meters within five days or even less. There is a very high death rate. Per year about twenty so-called climbers die. That is kept strictly under lock by the government.

On Everest, reportedly two-thirds of the summit aspirants are prescribed performance enhancing drugs to increase their chances of summit success. Who is responsible for doping on the mountain, the climbers themselves or rather the doctors who hand over these drugs to them?

I have no idea to what extend climbers are doped on Everest. But I have no doubt that there are quite a lot using the “three D”: Diamox, Dexamethasone and Dexedrine. The mountaineers take Diamox for a long time, then Dexamethasone, a cortisone preparation, during the ascent and finally, to mobilize the last resources, Dextroamphetamine – a poison which was given to the Stuka pilots in the Second World War to make them more aggressive. In the history of alpinism, many climbers have died as a consequence of taking these amphetamines on Nanga Parbat and other mountains because they pushed themselves beyond their limits. Obviously this medication is prescribed by doctors. On the other hand, these drugs are also available illegally. Today you can get everything you want provided that you pay for it.

Actually, Diamox and Dexamethasone is emergency medicine.

This is certainly also a cause of the problem. I think Diamox is the most harmless of these. If someone makes this brutal ascent of Kilimanjaro within five days up and down, he is almost certainly a candidate for high altitude sickness. This can be avoided to a great extent by taking Diamox. It has few side effects. The beer tastes horrible, which is the worst side effect. You have to drink a little more water because it has a diuretic effect. But otherwise I personally recommend Diamox, if someone who wants to climb Kilimanjaro and has problems with high altitude asks me.

You were on top of Mount Everest in 1978, along with Reinhard Karl (Karl was the first German on Everest, he died in an ice avalanche on Cho Oyu in 1982). Four years later you suffered from a high altitude cerebral edema at Cho Oyu almost killing you. How can this be explained? You really had to assume that you can handle high altitude well.

I was not able to bear high altitude as good as, for example, Reinhold Messner but quite properly, when I had acclimatized. But I always had this time pressure. I was working in the hospital. I wanted to get as high as I could as quickly as I could in the few days I had left for mountaineering. In 1982, I had a severe high altitude cerebral edema. In 1985, on Makalu, we moved within nine days from Zurich up to 7,000 meters. There I had a life-threatening high altitude pulmonary edema. I would have died if I had not tried for the first time a therapy which then worked. I took the heart medication Nifedipine, which lowers the increased blood pressure in the pulmonary circulation, which is especially crucial in the case of a high altitude pulmonary edema. That saved my life. Afterwards I have made the appropriate studies, and we were able to prove that this drug can be used as a prophylaxis for people who are predisposed to high altitude pulmonary edema. In my opinion this isn’t doping. Furthermore we could show that in case someone is already suffering from a high altitude pulmonary edama, it can improve the situation significantly. Meanwhile, it has been found that the same effect can be achieved by Viagra. It widens the vessels also in the lungs, not just below. Thus the increased pressure in the pulmonary circulation decreases, and the people are doing better. This is, of course, more fun than taking a heart medication.

You referred to prophylaxis. Is it really practiced?

I know people who do it. In 1989, we published a work in the “New England Journal of Medicine”, the leading journal in the medical scene, in which we showed that people with a predisposition to high altitude pulmonary edema can be protected to a certain extent by prophylaxis with this cardiac medication. People who e.g. suffered from a high altitude pulmonary edema even in the Alps at an altitude of 3,000 to 3,500 meters should be recommended such a prophylaxis. Of course, it would be wiser to tell them: “Stop this stupid mountaineering, instead swim, run or whatever!” But these people are not teachable. They want some medicine.

You had the privilege of traveling in the Himalayas at a time, when it was still a deserted mountain region without any tourism. How do you think about what is going on there today?

I follow what’s happening today in the Himalayas with fascination. It is unbelievable what the young really good climbers do in the difficult walls of the seven-thousanders. What I am following with great sadness is what takes place on Everest and on the other commercialized eight-thousanders. These endless queues of clients who are pulled up by their Sherpas – I think that’s an embarrassing spectacle.