Pushed to the margins

Imagine a society where some members are not allowed to speak to others, except from a distance of 100 meters, where generations of these ‘untouchables’ are banished to the village’s outskirts because they clean out the garbage and who are physically beaten up if they do not follow their community’s norms. If you took a trip to Tumkur in southern India about 30 years ago, you would have seen this happening with your very eyes.

The Dalits have been suppressed because of their low status within India’s caste system. There are four main castes among the Hindus in India; the Brahmins (scholars and priests) are the topmost caste, followed by the Kshatriyas (the warriors), the Vaishyas (merchants and landowners) and the Shudras (manual labourers). A further, fifth group is used to describe those who collect garbage, clean toilets and everything else that is considered dirty. The Dalits fall into this category and have been forcibly kept far away from mainstream society because of the “impure” nature of their work.

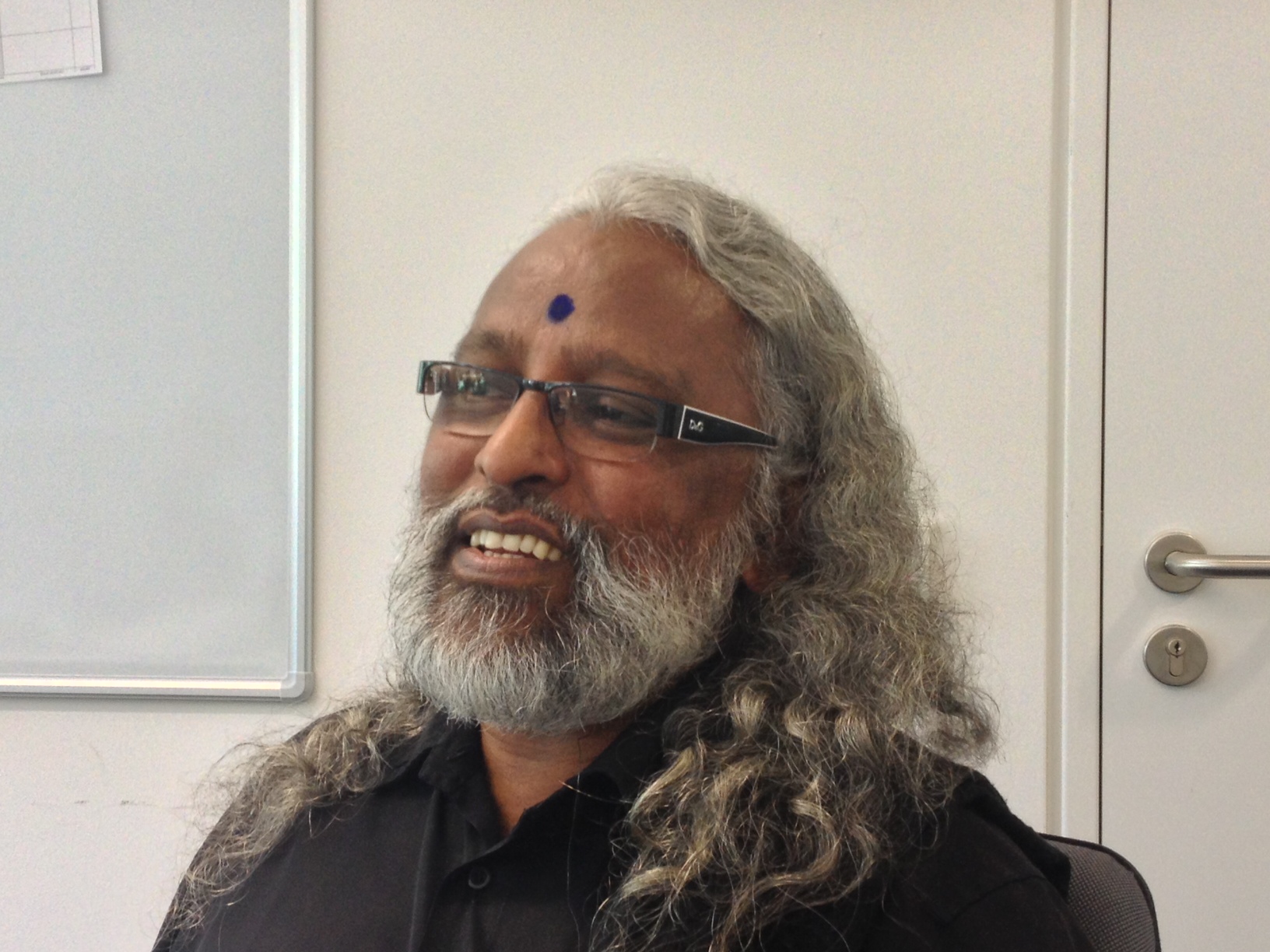

Manickam Casimir Raj, one of the pioneers in the campaign against untouchability in India, spoke to Women Talk Online about his movement for the Dalits (which literally means, “the crushed”) in Tumkur and how his organization envisions a holistic and inclusive approach towards lessening discrimination. He has been working in this area since the 1980s. He also speaks about the special role of Dalit women.

Manasi Gopalakrishnan: What are the kinds of discrimination that the Dalits in Tumkur had to face?

M.C. Raj: Common untouchability practices, like having two separate sets of glasses for untouchables and normal people in restaurants, a lack of access to public places like community halls or the local dairy. We even had some incidents where Dalits were not allowed to draw water from government wells.

We also have a very obnoxious festival called the Marama in which the Dalits are expected to do everything free of charge. They have to sweep the streets, clean the drains, if someone dies in the village, they have to beat the drums free of charge, the have to dig the graves of the dead free of charge and they get a bottle of brandy or liquor in return.

Have these practices now come to an end?

We have completely removed these practices from Tumkur district and have begun projects in 10 other districts. But our main focus has been on the history and culture of the Dalit people, so we are not crying foul at the other castes all the time.

Now we are in a peace-building process because the Dalit people have found their strength.

What do you mean by this “culture?”

When we speak of culture, we mean the primacy of women. This is a part of Dalit culture. Indigenous peoples all over the world celebrate women. The major focus in this culture is worshipping the earth as our mother. This culture is body-centric, women centric and cosmic-centric. It emphasizes that we are not here to dominate nature, that we should be in harmony with the changes in nature and not destroy ecology.

How does this “primacy of women” manifest itself in the Dalit culture?

If you look at Dalits today, it is the woman who holds the family together. Our men have been hopeless in the past and present. We have lost our land because of our men; we have lost our dignity and education because of men. Men have brought the Dalit community to where we are today.

Whatever we have left today, of our culture, is because of the women. If a man earns money and gives part of it to the woman, she ensures the maintenance of the family in a judicious way. When there is a conflict in the village, the Dalit women make peace.

Has India’s liberalization helped the Dalits come up in society?

We cannot say that. Let me give you the example of my daughter. When my daughter was filling out forms for jobs and further studies, she was asked what her caste was and she wrote, “Dalit” and when she was asked about her religion, she said, “Dalit.” She went on to study law and when she applied for internship, she was denied a position by every firm.

Do you think the “Dalit” label was a problem?

Yes, in the industry it is the same. They speak a flowery language of being inclusive and giving space to everyone who has the ability, but this Dalit label sticks. It is very difficult for the outside observer to identify.

I am not against modernization, but most Dalits are being pushed to the periphery. They have to travel into the city to earn their livelihood. This is difficult, because they have to pay for transportation. Under the pretext of beautifying the city, those who actually help make the city beautiful are pushed out of it.

Interview: Manasi Gopalakrishnan

Editor: Grahame Lucas