Search Results for Tag: Greenland

Arctic plastic “garbage patches”

There are a lot of things you might want to discover on a research cruise in the Arctic. Chunks of plastic floating around are not amongst them. But that is just what biologist Melanie Bergmann and her colleagues from the Alfred-Wegener-Institute and the Belgian Laboratory for Polar Ecology repeatedly did find while they were cruising through the Fram Strait, between Greenland and Svalbard.

They have just published a study documenting that plastic garbage has even reached the far north of the planet. In the online portal of the magazine Polar Biology, they describe how they found plastic waste floating on the surface of the ocean.

Plastic pollution – a fact of life?

In 2012, Bergmann and her colleagues took the opportunity of joining a cruise on the German research ship Polarstern to the Fram Strait to measure the extent of plastic pollution there. They monitored the ocean surface from the boat and a helicopter. Over 5,600 kilometres they found 31 pieces of plastic rubbish. But that will only be the tip of the “garbage-berg”.

“Since we were counting from the bridge of the ship, which is 18 metres above the sea surface, or from the helicopter, we primarily found large pieces of flotsam”, Bergmann told journalists. “So our figures very probably under-estimate the actual amount of garbage”, she added.

Too beautiful to “waste”? The team even found plastic waste in Greenland’s Ice Fjord (Pic: I. Quaile, Ilulissat)

Plastic waste tends to disintegrate into small pieces, just one or two centimeters in size, if they float in the sea for any length of time.

Somehow, the results of this study did not really surprise me. That, I think, is a very sad state of affairs. There have been so many reports of plastic particles being found in animals and birds and so in our human food chain that there is a danger we take this serious form of pollution for granted. The ngo Ocean Care estimates that around nine million tons of plastic waste finds its way into the oceans every year.

The seabed as a waste dump?

The AWI scientists say this is actually the first study to show that plastic waste is floating around on the surface of Arctic waters. For an earlier study, the German biologist searched for plastic, glass and other waste on photos taken of the Arctic seabed. She found that even in deep sea areas, the amount of garbage has increased in recent years. The concentration is 10 to 100 times higher than on the surface. The experts deduce from this that garbage ultimately sinks to the bottom and collects there.

Plastic bag at the HAUSGARTEN, the deepsea observatory of the Alfred Wegener Institute in the Fram Strait. This image was taken by the OFOS camera system in a depth of 2500 m. Photo: Alfred-Wegener-Institut/Melanie Bergmann/OFOS

The question is: how does this waste get up into the Arctic? It could, it seems be part of what, is described as a “garbage patch”, created when plastic waste gets caught up in ocean currents and concentrated into a kind of whirlpool.

Scientists have already identified five of these patches around the globe. The waste in the Arctic appears to be part of a new, sixth “patch” developing in the Barents Sea. What a depressing development! Scientist Melanie Bergman thinks it probably contains waste from the densely populated coastal regions of northern Europe.

“It is thinkable, that some of this garbage drifts north and northwest, as far as the Fram Strait”, she says. Another theory, she says, it that the garbage being found in the Arctic is caused by the retreat of sea ice.

“More and more fish trawlers are following cod further north. Presumably, rubbish from the ships ends up in Arctic waters, either deliberately or by accident. We are assuming that this trend will continue”, says Bergmann.

Climate change and pollution threat

So while here in Bonn, just across the road from my office, the UN climate secretariat is struggling to come up with a draft text for the Paris COP21 summit, which will be acceptable to all parties (and so subject to so many compromises and loopholes?), we have yet another sign of a climate change impact on the no-longer-pristine Arctic. And at the same time, it indicates the effects our unsustainable lifestyles are having on the environment of the planet. I have been witness to many arguments over whether governments should put more effort into combating climate change or environmental degradation and pollution. Ultimately, once more I come to the conclusion that it is virtually impossible to separate the two.

Last week I interviewed two experts on different aspects of ocean protection for a Living Planet special: Oceans under Pressure. They expressed similar views on the intrinsic connections between climate change, humans’ maltreatment of the environment and the health of the oceans on which we rely for survival. Not only are we causing climate change. The other pressures we put on the oceans make it less able to cope.

Tony Long is in charge of work against illegal fishing with Pew Charitable Trusts:

“I think climate change, over-fishing and illegal fishing are all linked in one way or another. The bad practices that occur from illegal fishing can damage the ecosystem, whether it be trawling and ripping up corals, or fishing the wrong species at the wrong time. It all has an effect on the broader ecosystem. And with ocean acidification and the changes that are taking place now scientifically proven, that’s going to reduce the amount of fish people can catch, if we don’t start to look after it. So actually it should all be seen as one”. (Read the interview here).

Ove Hoegh-Guldberg is Director of the Global Change Institute at the University of Queensland, Australian, and chief scientist with the XL Catlin Seaview Survey, which has been monitoring the state of the world’s coral reefs, including the current global bleaching event:

“On our current track where we’re polluting local water, we’re overfishing coral reefs and now we’re rapidly changing the temperature and acidity of the ocean, we won’t have coral reefs and it will be a very long time before they come back – probably well after our exit from the climate. We are the first generation to see these types of impact and we are going to be the last that has the chance to do something. We must get to very low CO2 emission rates as soon as possible, hopefully over the next 20 to 30 years. Because if we don’t – it won’t just be coral reefs. It will be a large number of other ecosystems that go, and humanity will be in trouble.” (Read the interview here.)

I rest my case.

Can we still avert irreversible ice sheet melt?

Earlier this week, I was able to follow up my last talk with Professor Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), after he returned from the Paris climate science forum. After the publication of the study he was involved in on paleoclimatic data linking global temperature with sea level rise, and having heard his views on the science consensus ahead of the December UN summit in Paris, I wanted to know how he views the prospects for the polar ice sheets.

A question I return to often is whether anything we do to reduce emissions from now onwards – given that huge damage has already been done by our fossil fuel emissions and that the CO2 will remain in the atmosphere for a very long time to come – can prevent the ice sheets in the Antarctic and Greenland from reaching a “tipping point”.

Professor Rahmstorf gives this definition of a “tipping point” – which can mean different things to different people in different contexts:

“Climate tipping points are points of no return, where you cannot stop a process that has been set in motion. It’s a bit analogous to the situation where you are sitting in a rowing boat and you lean over a bit to one aside and not much happens. Then you lean a bit more and a tipping point comes where the boat simply tips over. One of these points of no return is with our continental ice sheets, where their further melt-down becomes inevitable and unstoppable. And we have to realize that we have enough continental ice on this planet to raise global sea level by more than 60 metres. That means we cannot afford to lose even a very small fraction of that ice without drowning coastal cities and small island nations.”

Is the boat still afloat?

But, of course, we are already losing ice at a worrying rate. Rahmstorf cites recent research showing that at least a part of the West Antarctic ice sheet has already been destabilized.

“We probably have already crossed the tipping point for a part of West Antarctica. That is probably going to already commit us to about three metres of sea level rise.”

Of course this is not likely to happen in the very near future. But the problem with the tipping points is, of course, that there is no going back, as Rahmstorf explains:

“Sea level has already risen 20 centimetres globally since the late 19th century, due to modern global warming, which is very basic physics. It’s melting continental ice sheets. And also the oceans are being heated up, which expands the ocean water, because warm water takes up more space. And by the year 2100, with unmitigated emissions, we are looking at one meter of sea level rise, which already, for vulnerable coastal areas like delta regions, like Bangladesh for example, will dramatically increase the storm surge risk. But sea level rise will not stop in the year 2100, because the ice sheets are actually quite slow to melt, and within the next decades, we will be causing a long-term sea level rise commitment by several metres for every degree of global warming that we cause.”

Greenland – and Miami, St. Petersburg, Bangladesh…

Record melting appears to be happening on Greenland at the moment. I asked Rahmstorf how safe the world’s biggest island and the largest area of freshwater ice in the northern hemisphere (See also the Ice Island in Pictures) is from reaching a point of no return. He wasn’t able to give a reassuring answer:

“We don’t know exactly where the tipping point is for the Greenland ice shield is. The IPPC estimates anywhere between one and four degrees of global warming. We are already at one degree warming, so we may well cross that tipping point in the next decades.

In the review of the relation between global temperature and sea level rise from polar ice disintegration I discussed in the last blog post, Rahmstorf and his colleagues found that just a slight further rise in temperature might equate to a rise in global sea level of up to six metres. I asked him what that would mean for the world right now:

“There would be quite a number of large coastal cities I cannot imagine could still be defended. Think of New York city for example. Or Miami would be one of the first cities to go. St. Petersburg, Alexandria, Manila – you name them. Once you are talking about metres of sea-level rise, the consequences would be quite catastrophic. Especially as it is to be feared that people will not react proactively by move away from the danger zone, but will probably stay in their cities until a major storm surge hits. Like Hurricane Katrina hitting New Orleans, which also was a case where experts had warned for a long time that the city was in danger, once the next hurricane strikes, but people still didn’t act according to the precautionary principle. As they should have, and as we must do to prevent a climatic disaster in future.”

Can we keep the ice chilled?

So what would we have to do to keep sea level in check?

“Emissions would have to be close to zero by mid-century, so we are not talking about small cosmetic adjustments, but a transformation of our energy system, decarbonization, that is getting out of the carbon-based energy system. The good news is that the technologies to do that are available. It’s all about mustering the political will. And, of course, fighting the particular interests which are opposing this transformation.”

Stefen Rahmstorf is not one of those scientists who prefer to sit on the fence and leave the interpretation of his research and their implications up to the politicians. He is convinced only rapid action to stop emissions can prevent catastrophic climate change – including the melt of the polar ice.

I have interviewed him on previous occasions in the last few years. This time, I was surprised by his optimistic stance on whether the international community can still do anything in time to stop global warming from reaching the dangerous level of two degrees (or even one point five, as Rahmstorf and others say would be far preferable):

“There’s still a good chance that a strong agreement coming out of the Paris summit in December could mean we could avoid the Greenland tipping point. I am cautiously optimistic that Paris will reach a meaningful agreement, not necessarily one that guarantees that we will stay below two degrees global warming, but one that will be seen in hindsight as a real turning point, from where emissions started to fall soon after. The key point is – the sooner we stop global warming, the better the chances are that we avoid future critical tipping points.”

All we need, says Rahmstorf, is the political will to make use of the technologies available, take on the fossil fuels lobby, and clean up our energy system.

Listen to my interview with Stefan Rahmstorf on DW’s Living Planet this week.

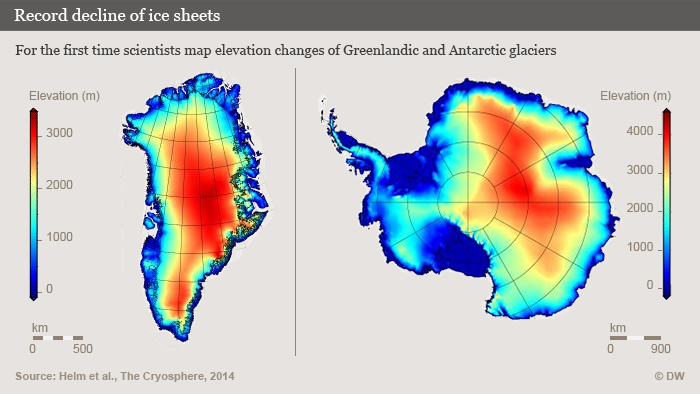

Polar melt confirmed from space

I am disappointed that there was so little mainstream media coverage (please correct me if I am wrong) of a report from a team of scientists from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) in Bremerhaven who have analysed just over two years of data from the CryoSat-2 satellite. Their conclusion that the Greenland ice sheet and Antarctica’s glaciers are melting at record pace, dumping some 500 cubic kilometers of ice into the oceans every year, twice as much in the case of Greenland and three times as much in the case of Antarctica, by comparison with 2009 – yes, you read right, we are talking about a very short period for such a dramatic increase in ice loss – should have made more news headlines and not just the science pages.

To understand the scale of that, the researchers say it would be the equivalent of an ice sheet that’s 600 meters thick and covers an area as big as the German city of Hamburg – or, my colleagues here at DW calculate, as big as Singapore.

The research team headed by Veit Helm used around two years’ worth of data from the ESA CryoSat-2 satellite to create digital elevation models of Greenland and Antarctica. The results were published in the online magazine of the European Geoscience Union (EGU) The Cryosphere.

“The new elevation maps are snapshots of the current state of the ice sheets,” Helm says. “The elevations are very accurate, to just a few meters in height, and cover close to 16 million square kilometers of the area of the ice sheets.” He says this includes an additional 500,000 square kilometers that weren’t covered in previous elevation models from altimetry.

Space technology shows declining ice mass

Helm and his team analyzed all data from the CryoSat-2 radar altimeter SIRAL in order to come up with the detailed maps. The satellite with this new radar equipment was launched in 2010. Satellite altimeters measure the height of an ice sheet by sending radar or laser pulses which are then reflected by the surface of the glaciers or surrounding areas of water and recorded by the satellite.

The researchers used other satellite data as well to document how elevation has changed between 2011 and 2014.

Rapid ice loss over a short period of time

The team used more than 200 million SIRAL data points for Antarctica and some 14 million data points for Greenland to create the elevation maps. The results show that Greenland alone is losing around 375 cubic kilometers of ice per year.

Compared to data which was collected in 2009, the loss of mass from the Greenland ice sheet has doubled. The rate of ice discharge from the West Antarctic ice sheet tripled during the same period.

I think this is definitely worth talking about. We know the huge implications of polar ice melt for global sea levels. Other research from this year also tells us that, at least in the case of parts of Antarctica, the ice melt is probably irreversible.

We cannot afford to ignore what is happening to the ice sheets. The extent of ice loss in Greenland is particularly dramatic. I am losing patience with those people who respond to studies like this and our reporting on it by saying “but the East Antarctic is gaining volume” and “the Antarctic sea ice has grown”. It is so easy to take things out of context and mix different factors up when trying to understand a very complex system.

I will give the last word here to AWI glaciologist Angelika Humbert, who co-authored the study: “If you combine the two ice sheets (Greenland and Antarctic), they are thinning at a rate of 500 cubic kilometers per year. That is the highest rate observed since altimetry satellite records began about 20 years ago.” It seems to me there is no arguing with that.

Related stories:

Antarctic melt could raise sea levels faster

West Antarctic ice sheet collapse unstoppable

Climate change risk to icy East Antarctica

Antarctic Glacier’s retreat unstoppable

Human action speeds glacial melting

It might sound like stating the obvious, but in fact it is not easy to find clear evidence that human behavior is behind the retreat of glaciers being monitored in different parts of the world. Hence my interest in a study just published in the journal Science.

The main problem is that it usually takes decades or even centuries for glaciers to adjust to climate change, says climate researcher Ben Marzeion from the Institute of Meteorology and Geophysics of the University of Innsbruck. He and his team of researchers have just published the results of a study for which they simulated glacier changes during the period from 1851 to 2010 in a model of glacier evolution. They used the recently established “Randolph Glacier Inventory” (RGI) of almost all glaciers worldwide to run the model, which included all glaciers outside Antarctica.

“Melting glaciers are an icon of anthropogenic climate change”, the authors say. However, they stress that the present-day glacier retreat is a mixed response to past and current natural climate variability and “current anthropogenic forcing”. Their modeling shows though that whereas only 25% of global glacier mass loss between 1851 and 2010 can be attributed to human-related causes, the fraction increases to around 69% looking at the period between 1991 and 2010. So human contribution to glacier mass loss is on the increase, the experts write.

Marzeion says the global retreat of glaciers observed today started around the middle of the 19th century at the end of the Little Ice Age, responding both to naturally caused climate change of past centuries (like solar variability), and to human-induced changes. Until now, the real extent of human contribution was unclear. The authors say their latest piece of work provides clear evidence of the human contribution.

Once more I am happy to refer to the Climate News Network, in this case to Tim Radford, for an easy-to-read summary of the main research results and the background. There is no doubt that glaciers are losing mass, retreating uphill and melting at a faster rate, says Radford. He refers to some Andes glaciers and the the Jakobshavn glacier in Greenland, or Sermeq Kujualleq as I prefer to call it, using the indigenous name. Ice Blog followers may remember my own trip to Greenland and that particular glacier. I have also written on the speeding of the melt there on the Ice Blog and on the DW website.

Alpine glacier like these in Saas-Fee, Switzerland, have declined dramatically in recent decades. (I.Quaile)

Radford also refers to ascertaining the melting of alpine glaciers by comparing historic paintings and other documentation with the current ice mass. That decline is something I have observed at first hand in Valais in Switzerland during regular visits over the past 30 years. Look out for a comparative photo gallery of my own pics, when I get time to put it together. Since most of the shots are from the pre-digital era, that will be a time-consuming task.

I also remember a trip to the Visitor Centre of the Begich Boggs glacier in Alaska in 2008. The glacier has already retreated so far you can’t see it at all from the Centre built specially for the purpose of viewing it.

The question until now was how much of all this was caused by natural developments and how much to changes in land use and the emission of greenhouse gases? The latest study supported, among others, by the Austrian Science Fund (FWF) and the research area Scientific Computing at the University of Innsbruck, has come up with some answers. Since the climate researchers were able to include different factors contributing to climate change in their model, they can differentiate between natural and anthropogenic influences on glacier mass loss

“While we keep factors such as solar variability and volcanic eruptions unchanged, we are able to modify land use changes and greenhouse gas emissions in our models,” says Ben Marzeion, who sums up the study: “In our data we find unambiguous evidence of anthropogenic contribution to glacier mass loss.”

As always, there is still need for further research – and a lot more monitoring. The scientists say the current observation data is insufficient in general to derive any clear results for specific regions, even though anthropogenic influence is detectable in a few regions such as North America and the Alps, where glaciers changes are particularly well documented.

With global glacier retreat contributing to rising sea-levels, changing seasonal water availability and increasing geo-hazards, the study’s conclusions should help put a little more pressure on the world’s decision-makers to get serious about emissions reductions.

Arctic birds breeding earlier

Migratory birds that breed in the Arctic are starting to nest earlier in spring because the snow melt is occurring earlier in the season. This is confirmed by a new collaborative study,”Phenological advancement in arctic bird species: relative importance of snow melt and ecological factors” published in the current online edition of the journal Polar Biology. The scientists, including Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) biologists, looked at the nests of four shorebird species and one songbird in Alaska, recording when the first eggs were laid in the nests. The work was undertaken across four sites ranging from the oilfields of Prudhoe bay to the remote National Petroleum Reserve of western Arctic Alaska.

The scientists looked at nesting plots at different intervals in the early spring. Other variables, like the abundance of nest predators (which is thought to affect the timing of breeding) and satellite measurements of “greenup” (the seasonal flush of the new growth of vegetation) in the tundra were also assessed as potential drivers, but were found to be less important than snow melt.

Lead author Joe Liebezeit from the Audubon Society of Portland says “it seems clear that the timing of the snow melt in Arctic Alaska is the most important mechanism driving the earlier and earlier breeding dates we observed in the Arctic. The rates of advancement in earlier breeding are higher in Arctic birds than in other temperate bird species, and this accords with the fact that the Arctic climate is changing at twice the rate.”

Over nine years, the birds advanced their nesting by an average of 4-7 days. The researcher says this fits with the general observation of 0.5 days per year observed in other studies of nest initiation in the Arctic, of which, they say, there are not very many. The rates of change are much higher than those of observed in studies of temperate birds south of the Arctic.

Co-author Steve Zack from WCS says “Migratory birds are nesting earlier in the changing Arctic, presumably to track the earlier springs and abundance of insect prey. Many of these birds winter in the tropics and might be compromising their complicated calendar of movements to accommodate this change. We’re concerned that there will be a threshold where they will no longer be able to track the emergence of these earlier springs which may impact breeding success or even population viability”.

WCS Beringia Program Coordinator Martin Robards says “Everything is a moving target in the Arctic because of the changing climate. Studies like these are valuable in helping us understand how wildlife is responding to the dramatic changes in the Arctic ecosystem. The Arctic is so dramatically shaped by ice, and it is impressive how these long-distance migrants are breeding in response to the changes in the timing of melting ice.”

In connection with Migratory Bird Day some time ago, I talked to Ferdinand Spina, head of Science at Italy’s National Institute for Wildlife Protection and Research ISPRA, in Bologna, Italy. He is also in charge of the Italian bird ringing centre, and Chair of the Scientific Council of the UN Convention on Migratory Species, CMS. In the interview, he stressed that climate change is becoming one of the greatest threats to birds that breed in the Arctic.

“Birds are a very important component of wildlife in the Arctic. There are different species breeding in the Arctic. The Arctic is subject to huge risks due to global warming. It is crucially important that we conserve such a unique ecosystem in the world. Birds have adapted to living in the Arctic over millions of years of evolution, and it’s a unique physiological and feeding adaptation. And it is our duty to conserve the Arctic as one of the few if not the only ecosystems which is still relatively intact in the world. This is a major duty we have from all possible perspectives, including an ethical and moral duty, ” he says. We talked about the seasonal mismatch, when birds arrive too early or too late to find the insects they expect to encounter and need to feed their young.

This reminds me of a visit to Zackenberg station in eastern Greenland in 2009. At that time, Lars Holst Hansen, the deputy station leader, told me the long-tailed skuas were not breeding because they rely on lemmings as prey. The lemmings were scarce because of changes in the snow cover.

Jeroen Reneerkens is another regular visitor to Zackenberg, as he tracks the migration of sanderlings between Africa and Greenland. A great project and an informative website!

Morten Rasch from the Arctic Environment Dept of Aarhus University in Denmark is the coordinator of one of the most ambitious ecological monitoring programmes in the Arctic. The Greenland Environment Monitoring Programme includes 2 stations, Zackenberg, which is in the High Arctic region and Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, in the “Lower” Arctic. Hansen and other members of Rasch’s teams monitor 3,500 different parameters in a cross-disciplinary project, combining biology, geology, glaciology, all aspects of research into the fragile eco-systems of the Arctic. At that time, he told me during an interview, ten years of monitoring had already come up with worrying results:

“We have experienced that temperature is increasing, we have experienced an increasing amount of extreme flooding events in the river, we have experienced that phenology of different species at the start-up of their growing season or the appearance of different insects for instance now comes at least 14 days earlier than when we started. And for some species, even one month earlier. And that’s a lot. You have to realise the entire growing season in these areas is only 3 months. When we start up at Zackenberg in late May, or the beginning of June, the ecosystem is completely covered in snow and more or less frozen, and when we leave, in normal years – or BEFORE climate change took over – then we left around 1st September and the ecosystem actually started to freeze up. So the entire biological ecosystem only has 3 months to reproduce and so on. And in relation to that, a movement in the start of the system between 14 days and one month – that’s a lot.”

Listen to my radio feature: Changing Arctic, Changing World

I can’t write about birds and climate change in the Arctic without finishing off with a mention of George Divoky, an ornithologist whose bird-monitoring has actually turned into climate-change monitoring on Cooper Island, off the coast of Barrow, Alaska. George looks after a colony of Black Guillemots and spends his summer on the island. In recent years, he has taken to putting up bear-proof nest boxes for the birds, because polar bears increasingly come to visit, as the melting of the sea ice has reduced their hunting options. He has also observed the presence of new types of birds which die not previously come this far north.

Feedback