Search Results for Tag: poverty

Inventor’s deposit ring puts change in a bottle

Germany is known for its strong social system. Still, it’s not uncommon to see people in need of some extra cash rummaging through public trash cans for old bottles that carry a deposit.

Beer bottles are worth just 8 cents, but most plastic bottles can be redeemed for 25 cents. For some people, it’s not worth the trouble of taking them back to the store to get their deposit. But for others, a bag full of bottles can mean one more warm meal.

Paul Ketz in Cologne was bothered by all the deposit bottles he saw being thrown away, knowing that they were valuable to the less fortunate – not to mention the damage excess waste causes the environment.

So the 25-year-old came up with a brilliant idea that’s been catching on, not only in Cologne, but across Germany. Watch the video by Carl Nasman for a glimpse into Paul Ketz’s workshop:

Listen to Carl Nasman’s full report from Cologne for the whole story:

Cologne was the first city in Germany to order the rings (Copyright: 2013 Pawn Ring by Paul Ketz / Photo: Markus Diefenbacher)

Most plastic bottles are worth 25 cents, glass are worth only 8 cents (Copyright: 2013 Pawn Ring by Paul Ketz / Photo: Markus Diefenbacher)

The rings are starting to catch on across Germany (Copyright: 2013 Pawn Ring by Paul Ketz / Photo: Markus Diefenbacher)

First published on April 29, 2014

Schooling meets soccer in Mumbai’s slums

India is a country of cricket-lovers, so can soccer catch on?

Ashok Rathod is convinced that soccer is the best way to give kids growing up in the slums a second lease on life. Teamwork, leadership, respect and communication come out of the game for 22 players.

Having grown up in a Mumbai slum himself, Ashok knows exactly which problem the kids there face. Many start drinking and gambling as young as 10, he says, then get married early and drop out of school.

Committed to make a difference, Ashok founded the Oscar Foundation in 2006. The team organizes soccer practices and matches for young people – but also provides an education program aimed at giving school drop-outs basic literacy skills.

Listen to the report by Sanjay Fernandes in Mumbai:

Suraj (right) is Oscar’s associate director and Kumar (left) participated in the Oscar program and now works as a coach (Photo: S. Fernandes)

The Oscar Foundation focuses not only on soccer – but also on education programs (Photo: S. Fernandes)

First published on February 26, 2014.

Inventor’s deposit ring puts change in a bottle

Germany is known for its strong social system. Still, it’s not uncommon to see people in need of some extra cash rummaging through public trash cans for old bottles that carry a deposit.

Beer bottles are worth just 8 cents, but most plastic bottles can be redeemed for 25 cents. For some people, it’s not worth the trouble of taking them back to the store to get their deposit. But for others, a bag full of bottles can mean one more warm meal.

Paul Ketz in Cologne was bothered by all the deposit bottles he saw being thrown away, knowing that they were valuable to the less fortunate – not to mention the damage excess waste causes the environment.

So the 25-year-old came up with a brilliant idea that’s been catching on, not only in Cologne, but across Germany. Watch the video by Carl Nasman for a glimpse into Paul Ketz’s workshop:

Listen to Carl Nasman’s full report from Cologne for the whole story:

Cologne was the first city in Germany to order the rings (Copyright: 2013 Pawn Ring by Paul Ketz / Photo: Markus Diefenbacher)

Giving the homeless a voice

Homeless people are perhaps the most marginalized group in society. Those who sleep rough on the street are often ignored by the wider public, but Paris local Martin Besson has more empathy than most.

Despite having a home to go to, the 18-year-old chose to spend a night on the street to see what it was like to be homeless. The experience was confronting, and spurred the high school student into action. Last year he launched Sans A, an organization that aims to draw attention to the plight of homeless people – by giving them a voice on social media.

Martin spends his free time getting to know the less fortunate in Paris, and uploading their stories for the public to read. The idea, he says, is to break down the barriers between homeless people and the rest of society.

Listen to the report by Fabien Jannic-Cherbonnel in Paris.

Feeding forward in California

Every day, 263 million pounds of consumable food is thrown away in the United States – enough to fill a football stadium to the brim. At the same time, nearly one in six adults doesn’t know where their next meal will come from.

As president of Feeding Forward, a non-profit organization that fights food waste and hunger in the local San Francisco Bay Area, Chloe Tsang is working to change that.

The 20-year old student at UC Berkeley spends her spare time overseeing the website and app Feeding Forward created to make private food donations quick and easy.

Listen to the report by Anne-Sophie Brändlin in Berkeley, California:

Anyone who has more than 10 pounds of leftover food can snap a picture of it and post it to the website or the app. Feeding Forward then takes care of the rest. (Photo: Feeding Forward)

Chloe Tsang convinced Samuel Hernandez, the supervisor of Golden Bear Café at the UC Berkeley campus, to donate leftover food through Feeding Forward’s website (Photo: Anne-Sophie Brändlin)

A heart for the homeless

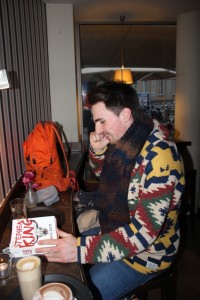

Kevin Hofmann, 22, spends a lot of time in cafes, where he likes to read books. When he noticed how much food his regular cafe was throwing away after closing time, he felt he had to take action. Now he regularly collects the unsold sandwiches and cookies and passes them out to the homeless people in his city, Bonn.

Germany has plenty of soup kitchens and shelters. But Kevin says why leave the work to other people? Instead, he’s taking responsibility himself – and breaking out of the apathetic stereotype of his generation.

Listen to the report by Nuradin Abdi in Bonn:

It’s taken a while for Kevin to gain the trust of the homeless people he distributes food too, but now Alexandra (left) is one of the people he meets regularly in downtown Bonn. (Photo: N. Abdi)

Hope for Chile’s poorest

Emil Schneider, a 19-year-old from Germany, was shocked to see with his own eyes that the poorest of the poor in Chile are not having their basic needs met. That’s why he signed up as a volunteer with TECHO, an organization that works with at-risks family in the slums.

Tamara Ramos, a coordinator for TECHO says the group’s aim is to empower those living in extreme poverty to find jobs so that they can reach long-term financial stability.

Listen to the report by Francisco Tapia in Vina Del Mar, Chile:

Emil says he was shocked to see basic human needs not being met on the streets in Chile’s slums (Photo: Emil Schneider)

Energy for Argentina’s poor

Getting access to enough energy for heating and electricity is a struggle for people living in Argentina’s poorer communities.

Diego Musolino, 31, has designed a solar water heater which he hopes will provide a cheap, renewable solution, while at the same time reducing his country’s carbon footprint. He co-founded the non-profit Energizar Foundation, which works to help solve social problems by using alternative energy.

Listen to the report by Eilís O’Neill in Buenos Aires, Argentina:

Diego Musolino (left) explains to Pablo Uviedo how to fill the solar water heater. (Photo: E. O’Neill)

Mabel Uviedo laughs as she prepares Argentina’s traditional mate tea for the Energizar Foundation’s employees and volunteers. (Photo: E. O’Neill)

Diego (center) and two volunteers assemble the solar water heater in the Uviedos’ backyard. (Photo: E. O’Neill)

The solar water heater, constructed entirely from materials made in Argentina, can heat water to about 50°C (122 degrees Fahrenheit). (Photo: E. O’Neill)

Woman climbs Mount Everest to end poverty

Maria da Conceição became the first Portuguese woman to climb Mount Everest. She did it to raise money so that more Bangladeshis living in poverty would have the chance to find a job and feed their families.

In her job as flight attendant with Emirates Airlines, Maria da Conceição lived in a world of luxury – first class flights and five stars hotels. But that changed eight years ago during a stopover in Dhaka, where she was faced with a different reality.

In Bangladesh, she witnessed impoverished children living on the street, with little access to food and clothes, let alone education.

“I couldn’t ignore the poverty that I saw with my own eyes. It was impossible for me to go back to my daily routine as a flight attendant and ignore what I saw there,” she told DW.

As a result, Maria da Conceição launched the Dhaka Project, helping almost 600 children, by giving them access to education, health care, food, clothes and community aid.

For the former flight attendant, it was “unbelievable” that these children “didn’t have any kind of rights.” Maria said that they were “forgotten” and “ignored” in Dhaka’s streets. “It took a foreigner to come and help them. Now they have some rights,” she said.

The Dhaka Project was a non-profit organization, so Maria had to fight for donations. The majority of funding came from Dubai, in the United Arab Emirates, while there has also been some help from Portugal, Maria’s home country.

The Dhaka Project recognized with the European Union Women Innovators Prize and the Emirates Woman of The Year Award.

Resistance and crisis

Maria criticizes the government of Bangladesh for hindering her work. “I am not welcome in their country. They didn’t give me a visa,” said Maria. And, last year, they even accused her of human trafficking.

“Those were rough times. I fought against that accusation and I said that it wasn’t true and instead of accusing me they should accuse their own country. That put an end to it,” she remembered.

The global economic crisis has also affected the work of The Dhaka Project. Since money was tight, Maria da Conceição decided to restructure the project. Now, it’s known as the Maria Cristina Foundation, named after Maria da Conceição’s foster mother.

“Now, the main focus is on parents. But, whenever a child up to 18 years of age has the opportunity to gain a scholarship, we provide support for the process,” she said.

She also says that she made an agreement with the British Council that enables parents to learn English. That, in turn, makes it possible for them to work in Dubai. Maria helps out with her connections to her last employer, Emirates Airlines. She left that job when a British family decided to take on the costs of the foundation for a two-year period.

“When these people arrive in Dubai they don’t have anything. We help them to buy everything that they need. We take them to the hairdresser, to the dentist and we give them pocket money for food,” she said. “When they start working, the first month goes unpaid, so the foundation helps them to live comfortably during that period of time. Once they receive their first salary, we do what families do when their children have their first job: You have your own salary, so now you don’t need our help anymore.”

Hardly finished with her first major goal, Maria has already set another (Photo: Maria da Conceição)

Climbing to great heights

Before the global economic crisis, Maria was able to help almost 600 children, but now, because of her tight budget, she can only help one family at a time. Because of that, she was forced to think outside the box. Climbing Mount Everest was a way to get media attention again and raise enough money to continue her work.

She started to prepare for the expedition to Mount Everest a year ago. The training was hard, but she is determined to succeed. “It was a very intense month. I had to go to school in India to learn how to climb a mountain. In Dubai I did conditioning, I did cycling; I had to climb stairs wearing a suit weighing 29 kilograms for at least four hours a day. The training was designed to break me in, physically and mentally,” she said.

And she made it. Maria da Conceição became the first Portuguese woman to climb Mount Everest and now she expects to have the funding she needs to follow up on what she started eight years ago – and help break the chain of poverty in Bangladesh.

But Maria wants to do even more. In November, she will start the 7-7-7 challenge: seven marathons in seven continents in seven days, in order to finance her project. After all, as she told DW, the children and the parents are her family now and her way of life. And after Mount Everest, she’s in great shape.

Go to the Maria Cristina Foundation’s website.

Author: Daniel Pinto Lopes

Editor: Kate Müser

Project runway in Buenos Aires

Many young women in the shantytowns of Buenos Aires struggle with drug abuse or unwanted pregnancy. Learning to walk with self-confidence can change that, says Guido Fuentes. So he opened a modeling school.

Listen to the report by Eilis O’Neill in Buenos Aires:

Feedback