Living with an identity crisis

‘The Underground Girls of Kabul’ sheds light on the various facets, effects and outcomes of the practice Bacha Posh in Afghanistan, where girls are brought up as boys in families that have no male members. (Credit: ArmyAmber, Pixabay)

Sex is, by definition, illegal in Afghanistan: The marriage contract is what finally turns it into a permissible act between husband and wife. Many a time, Afghan women joke about the unfortunate “chore” of being in bed with their husbands. But this “chore” becomes unbearable for women who have spent their entire childhood thinking they were boys. Bacha posh, or girls raised and presented to the world as boys, is a ‘hidden’ Afghan custom. In this excerpt from ‘The Underground Girls of Kabul’, published by Hachette India, writer Jenny Nordberg takes a look at the profound effects of the practice on the marital life of these women.

It was the most painful moment Shukria can recall. It was also the moment when she felt love for the first time. She knew then, at least to some degree, that she was a woman.

Giving birth made her certain there was something female in her, a confirmation that she did indeed have the body, and hopefully something more, of a woman. It came as a relief that she had perhaps not destroyed it altogether by being a man.

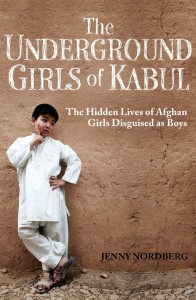

Book Cover: The Underground Girls of Kabul By Jenny Nordberg; Published by Hachette India; Pages 350; Pp: Rs 399

With all that she had tried to learn and observe – how to dress, how to behave, and how to speak – she finally would not have to worry that the other women would catch her slipping up.

She had the proof now: She was a mother. One of them. In all, she would have two sons and one daughter.

As for how children were created, it was not discussed much among her friends. No one wants to be known for knowing too much or seeming too willing to discuss anything to do with “the secret parts,” which is only one of the many ways Afghan women refer to their reproductive organs.

Sex is, by definition, illegal in Afghanistan: The marriage contract is what finally turns it into a permissible act between husband and wife. At times Shukria’s female friends joked about the unfortunate “chore” of being in bed with their husbands. About how everyone knows “what men are like.” Some husbands wanted to do it more often; others insisted only on Afghanistan’s Thursday-night conjugal tradition, when the workweek is over and both men and women take extra care to wash and groom in advance of Friday prayers. But Shukria did not dare ask any of her friends about what was normal and how anything related to the secret parts was supposed to feel or function. None of her friends ever mentioned enjoying sex, either, though they had all been told there were women who did: whores, with unnatural and obscene desires. And of course foreign women – more or less the same category.

Shukria’s own particular issue always seemed much too strange to bring up as well. None of her women friends grew up as boys, and she could not exactly ask her old male friends, either, why it is that sex makes her feel like “a nothing.” She laughs nervously when she tries to describe it: “I cannot give my husband love as a woman. I tried, but I think I got a very low score in this. When he touches me, I don’t feel comfortable. I just don’t feel anything. I want to ignore him. When he gets excited, I cannot respond. My whole body reacts negatively.”

What actually makes her cringe is not the physical contact, but shame: It is not right for her to be in bed with a man, even though she is his wife. “I don’t have those feelings other women have for men. I don’t know how to explain this to you….”

She looks at us and hesitates: “Sometimes it is very hard for me to be in bed with my husband because he is a man. I think I am also a man. I feel like a man myself, on the inside. And then I feel it is wrong, for two men to be together.”

So perhaps she is gay?

Shukria is not the least bit offended or embarrassed when after dancing around it for a while I finally just ask the question. She is almost sad to admit she feels no attraction to women, either. Avoiding them and cultivating a deep belief that they are the weaker sex brought no romantic allure for her. Being intimate with a woman would be wrong, too.

She is actually quite sure she prefers men over women in general: “Men are strong, strict. Women are very sensitive. I understand men. I feel them very easily.”

My question of whether Shukria, or other bacha posh, may automatically develop homosexual preferences by living as boys turns out to have been entirely misguided.

First of all, as Dr. Robert Garofalo, the expert in Chicago on development of gender, explains, growing up as a gender different from one’s birth sex does not by default translate to homosexuality in adult age. But perhaps most important, whether bacha posh become homosexual presupposes that women who live in Afghanistan have an opportunity to embrace, develop, or practice sexuality of any kind.

They do not.

In Afghanistan, sex is a means to an end, of adding sons to the family. But nowhere in that equation is a sexual orientation or preference a factor for women. Having sex with a husband in a forced marriage is an obligation – one fulfilled in order to have children. But when, or how, to have it is not a question of lust, willingness, or even conscious choice. To identify as either heterosexual or homosexual, and define what that means can be very difficult for an Afghan woman, who is not even supposed to be at all sexual.

(Excerpts from The Underground Girls of Kabul By Jenny Nordberg; Published by Hachette India; Pages 350; Pp: Rs 399)

Author: Jenny Nordberg

Editor: Marjory Linardy

This is an article from Women’s Feature Service

WTO RECOMMENDS

The face-off between tradition and modernity in India

Indian culture has incorporated a colorful variety of traditions and customs for hundreds of years. Even now, the values and norms of Indian culture play a significant role in Indian society. Especially for women there are more stringent rules, because they symbolize the honor of their families.

Paridhi Singh wanted to figure out how it would feel to meet a ‘phenomenal’ author like Maya Angelou. So she created this mock interview with the renowned women’s rights activist and poet, who passed away recently at the ripe old age of 86.

Maiden names: do they matter?

A new study conducted through Facebook by researchers from the University of York says more women now prefer to retain their maiden names after marriage. However many women still feel compelled by society to change their surnames as a mark of respect towards the new family as well as her husband.