Not secure in the ‘land of pure’

The mullah culture is a constant threat to new and secular feminism in Pakistan, writes feminist writer Ayesha Hasan.

It was 2009. The scorching summer sun pierced through the windows of one of the rooms in my grandmother’s house in Bannu, a small city bordering the Federally Administered Tribal Areas in the Pakistan’s northwestern Khyber-Pakhtunkwa province. The high ceiling fan made a soothing noise as the warm air dried the wet floor that had been freshly mopped. The phone rang. My cousin and I were too heat-stricken to pick it up, so we decided to let it ring; but the bell was unusually long that day, and louder than usual. It just didn’t sound OK.

I picked up. The voice on the other end uttered four cold words before hanging up. The sound of the fan, the heat of the sun and coolness of the semi-wet floor vanished for a few seconds.

“Ibrahim*, uncle has killed Sadia*.”

Sadia, a cousin, was set to marry another cousin the next day after her father had resisted the proposal for a year. But the father then shot her dead less than 24 hours before the big day because it was just too much for his “honor” to digest. He was taking her to “meet her physically handicapped aunt and to seek for her blessings”, but got her out on the roadside and shot her in the head instead and left her body on the roadside before he returned home to continue with the wedding preparations. Shortly before Sadia left with her father, she told her sister, “I know baba (father) is going to kill me,” but she liked to believe he wouldn’t.

Ibrahim still enjoys the same reputation in the business circle that he did before July 2009; and continues to live with the rest of his children and second wife in his house – a house he had built two decades ago after he divorced his first wife, a British Christian – Sadia’s mother.

A lack of evidence and cowardly witnesses saved him, but he is not alone. In Pakistan, 70 per cent of the perpetrators of honor crimes and violence against women never get reported, let alone charged – thanks to the pseudo protection laws that have more loopholes than articles and clauses. After 1979, the first time the controversial Hudood Ordinance was amended was in 2006 when the National Assembly passed the Women Protection Bill.

In Punjab alone, at least 5,800 cases of violence against women were reported in 2013. In 2011 and then in 2014 again, Thompson Reuters Foundation and World Report, respectively, termed Pakistan as the third most dangerous country in the world for women, with 1,000 ‘honor’ killings every year and 90 per cent of women facing some kind of domestic violence, most of which is cultural- and religion-triggered. Yet, there are major sections in Pakistani society that are not in favor of solidly legitimate law protecting women.

Mullahs against ‘un-Islamic’ Women Protection Bill 2016

On 24 February 2016, the Punjab government passed the Women Protection Bill, designed to protect women against crime and violence, including acid attacks, rape and domestic violence (Punjab accounts for 70 per cent of these cases reported across the country). Less than a week later, the first case was lodged by a woman who alleged that her husband had been violent towards her for over a year. The accused was arrested and investigations began. It all seemed unbelievably right for the first time, until a few days ago the Council of Islamic Ideology – a religious body that advises lawmakers whether or not legislation is compatible with Islam – and later more religious groups and clerics, termed the law ‘un-Islamic’ and demanded its nullification; the same clerics and religious groups who remain in a state of denial having said on record that “there were less than 1 per cent cases of violence against women in Pakistan”. Well, yes if we take this number for the percentage of cases reported.

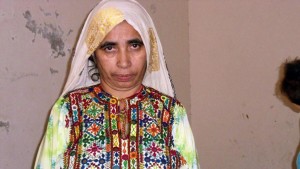

A woman who was ordered to be killed by her family in the name of honor. A women irrespective of her age is declared a ‘kari’ by the Jirga or the family council. She is killed either by her father or her brother. But few of them still manage to escape. © DW

Religious groups and leaders in Pakistan have now given the government until March 27 to abrogate the Act, while they continue with their psittacism against the law and empowerment of women.

Towards the end of feminism?

Feminism truly kissed Pakistan’s roads after 12 February 1983, when members of the Women’s Action Forum and Pakistan Women Lawyers’ Association were baton-charged at a rally. Today, Pakistan has more women lawyers, activists, social workers and journalists, who don’t miss a single chance to raise their voices for the protection of women and other rights. The number of women researchers is increasing likewise and there has certainly been a significant turn in the discourse of feminist politics in the Islamic Republic of Pakistan. However, this new and secular feminism that aims at empowering women constantly faces the risk of elimination due to extremist religious groups, discriminatory [religious] laws, gender stratification, social fragmentation and general resistance to steps which, if not guaranteed, at least give women a direction to follow for the realization of their rights and protection.

Despite a history of inconsistent political strategies regarding safeguarding women, the Pakistani government did take some very brave decisions in the last few weeks, including charging two brothers found guilty of ‘honor’ killing, and thus should not give up before a bunch of powerless clerics. Any debate around religion in Pakistan inevitably becomes dangerously poisoned with extremism and machismo; and these clerics need to be silenced once and for all if we don’t want another Saudi Arabia in the make and, more importantly, do not want to risk losing even one more Sadia.

*Identities have been changed.

Author: Ayesha Hasan

Editor: Marjory Linardy

Ayesha Hasan is a DW-FES Fellow of Journalism and is currently pursuing a PhD in women reporters and peace journalism at the University of Wollongong, Australia.

_____

WTO RECOMMENDS

Slain in the name of honor

I was begging and trying to hide myself behind my mother who was also begging for my life. She was asking my cousins to pardon me for bringing shame to the family. We kept pleading, but they shot me. I was dying, as the words “family honour” kept flashing across my mind. (From July 4, 2013)

The missing voices

This year’s bisextus for Pakistan was not just an intercalary day. It became a historical day that will be remembered for generations to come because of two news events: One was a film about horrendous practice of honor killings in Pakistan, the work of female documentary filmmaker Sharmeen Obaid-Chinoy, was recognized at the biggest award ceremony in the entertainment industry, the Oscars. (From March 8, 2016)

Muniba Mazari: Empowering Women and Girls in Pakistan

Muniba Mazari represents the modern woman in Pakistan. In a conservative country like Pakistan, she has broken the stereotypes. She is a writer, artist, singer, activist and a motivational speaker . The beautiful and attractive young female is also a paraplegic, having lost control of both legs after sustaining injuries in a car accident. Recently, UN Women, the United Nations entity for gender equality and the empowerment of women, named Muniba Mazari as Pakistan’s first female goodwill ambassador to advance gender equality and the empowerment of women and girls. (From February 5, 2016)