Free love and women: The sexual revolution 50 years on

In West Germany in the late 1960s, young people were demanding change – social, cultural and sexual change. What sparked the sexual revolution and what does it mean for women today?

The “sexual morals” of postwar West Germany were characterized by taboos and ominous warnings. Masturbating could lead to a degenerative disease, so they said; an erection was an abnormal swelling; the female orgasm was harmful.

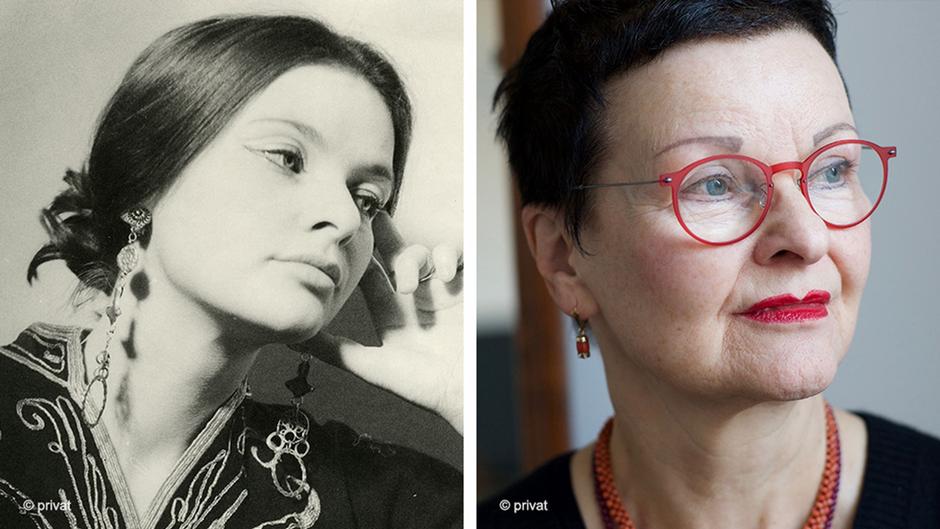

Sexuality was simply not talked about. It was something to be ashamed of, something from which children and young people should be protected. That’s how author and journalist Ulrike Heider remembers it.

She took part in the student protests that swept across West Germany in 1968 and were mirrored by similar protests elsewhere in Europe. In an interview with DW she says she will always be grateful to a student from the Socialist German Student Union who gave her her first “thorough sexual education.”

Ulrike Heider then and now – in books such as Vögeln ist schön (Screwing is Wonderful) and Keine Ruhe nach dem Sturm (No Lull After the Storm), she addressed issues of the student protest generation

‘My mother called me a whore’

The social and sexual conservatism of the 1950s was no coincidence: Clearly defined gender roles and romanticized domestic ideals were an attempt to get life back on track after the turmoil of the Second World War. Going against the grain was not the done thing.

“My mother expected that by the end of my twenties, at the very latest, I would marry a wealthy doctor or lawyer, have children and build a house,” Heider recalls. “When she found out that I had had sex with my first boyfriend – when I was 21 years old – she called me a whore.”

Along with the arrival of the contraceptive pill – which was introduced in the United States on August 18, 1960 and one year later in Germany – came a relaxation in the strict moral standards of the prude Adenauer era. This change paved the way for the 1968 movement to set out its demands for greater sexual freedom. Better and more accessible contraception meant people could have sex without worrying about the consequences. It gave women more control over their own bodies – now they could focus on education and academic studies instead of having babies.

In the 1950s, a stable family life trumped sexual satisfaction

Shaking off the shackles

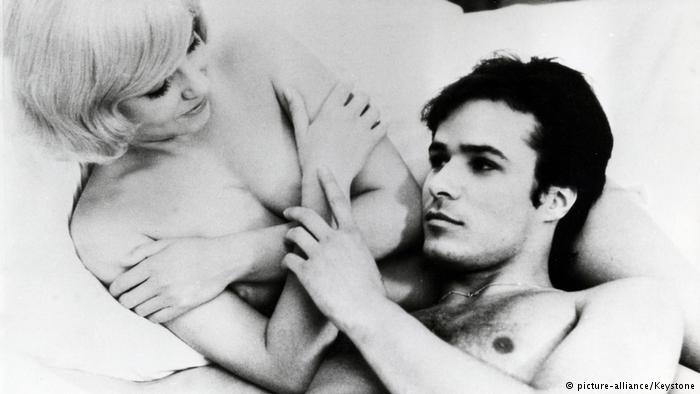

From the mid-1960s, the sexual wave flooded into the media, too. More female skin was on show than ever before – in ad campaigns, newspapers and, of course, in pornography. Sexual reformers in Germany, most notably Oswalt Kolle, began to use film as a tool for sex education.

But young revolutionaries in schools and universities went one step further. Heider explains that their goal was to connect the social revolution, which was already in motion in Germany, with a cultural and sexual revolution.

“Their Utopia was an egalitarian society… in which love and sexuality were freed from the moral chains of the church and state,” the author explains. “Traditional marriage and family life should be replaced by new, more personal relationships, expressions of love and sexual encounters.”

A scene from Oswalt Kolle’s “Wonder of Love” (1967)

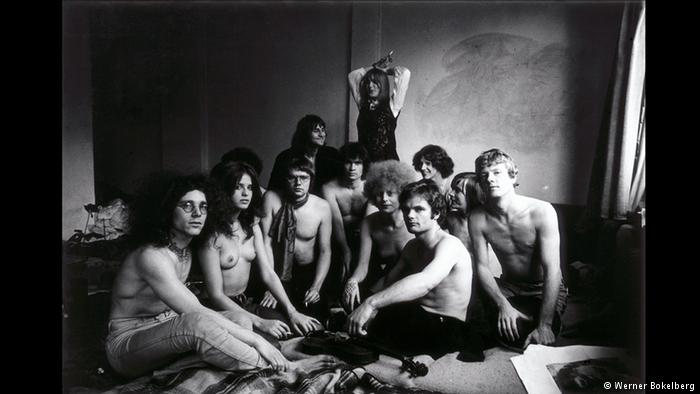

Free love and communal living

Communes brought singles together in shared accommodation. This new set-up, which allowed people to freely experiment with promiscuity, provided an alternative to the accepted model of love and family life. Seminars and study groups were founded to discuss sexual practices and problems. “And if someone got pregnant by accident, they could have an abortion without a guilty conscience,” says Heider. The sex taboo had been broken. Now it was all about pleasure, not procreation.

Feminist author Margarete Stokowski wrote in her 2016 book “Untenrum frei” (Free down below”): “This was a generation trying to show that it was different from all those who had been a part of the biggest crime in the history of mankind,” she wrote, referring to the Nazi era that overshadowed the generation before. She added that phrases like “Make love, not war” were used to make it clear that sex could in fact liberate you and allow you to take on the bad guys.

But for women, along with this sexual freedom came new pressures. Failing to live up to the sexually liberated image could mean you were branded sexually inhibited or a prude.

Margarete Stokowski was born in Poland and grew up in Germany

Within the revolution itself, women were still largely kept in the background at meetings. As Stokowski put it, they “should type leaflets rather than speak up.” One of the biggest problems was that sexuality was being revolutionized while gender roles remained unchallenged. This would finally change during the “second wave” of feminism, which in Germany was triggered by one woman, Sigrid Rüger, hurling a tomato at the head of the Socialist German Student Union in 1968 when the meeting refused to discuss demands made by female members.

50 years later…

And what about today, 50 years after the sexual revolution – can we finally talk of sexual self-determination? Take E. L. James’s “Fifty Shades of Grey” – erotic literature which brought BDSM (bondage, discipline, sadism and masochism) fantasies into the mainstream – for example. The series was welcomed by some as a groundbreaking depiction of female sexual emancipation. But viewed more critically, it could simply be seen as reinforcing the cliché of a shy girl who can only reach fulfilment with the help of a rich and sexually experienced man.

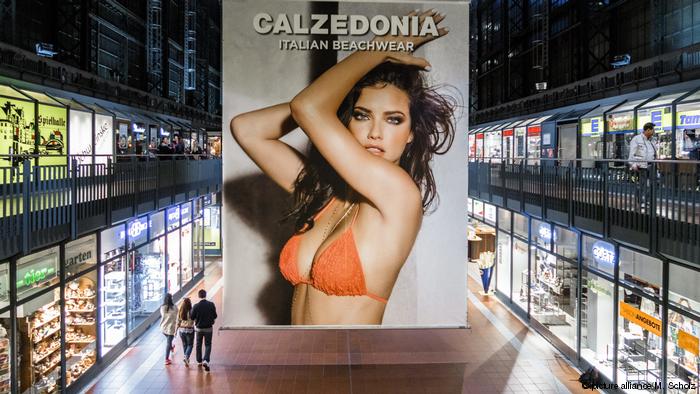

Sex sells: a subtle marketing campaign in Hamburg’s main station

Similarly, we are no longer shocked by the sight of female flesh in public. Half-naked women are everywhere – in film, advertisements, lifestyle magazines and in pop culture. Porn is easily available – for free – online. But does this represent sexual freedom or rather the successful commercial exploitation of sexuality?

For Heider, those who have cashed in on the latter are the real winners here. Stokowski points out that even today, half a century after the sexual revolution, the image of the sexually active woman is still so often connected to shame. The legacy of the ’68 revolutionaries is that sexual freedom made it onto the agenda – even if there is still a long way to go.

Author: Bettina Baumann (rls)