In German politics, women still have a long way to go

Yes, Angela Merkel has been in charge for 13 years, and Germany was a relatively early pioneer for women’s suffrage. But there’s still plenty of work to do to increase women’s representation in politics.

At a recent conference of Germany’s Christian Democrat (CDU) youth wing, Chancellor Angela Merkellooked out across the group’s leadership and had a laconic observation to share: “Very male,” she said.

“But 50 percent of the population is missing,” she continued, addressing the group of which just 5 of 16 state-level boards are led by women. “Women enrich life, not only private life but also political life. You don’t know what you’re missing.”

To the rest of the world, Germany may seem like a beacon for women’s political representation: For the last 13 years, the country has been led by Merkel, the world’s most powerful female politician. And it’s not just her: the leader of the center-left Social Democrats (SPD), Andrea Nahles, is also a woman; in the race to replace Merkel as head of the center-right Christian Democrats (CDU), one top candidate is her close ally and the party’s secretary-general, Annegret Kramp-Karrenbauer.

A century of small steps

As Germany celebrates the 100th anniversary of women’s suffrage on November 12th, however, it’s clear that the presence of women at the top levels of politics has not necessarily translated into similar success for other female leaders.

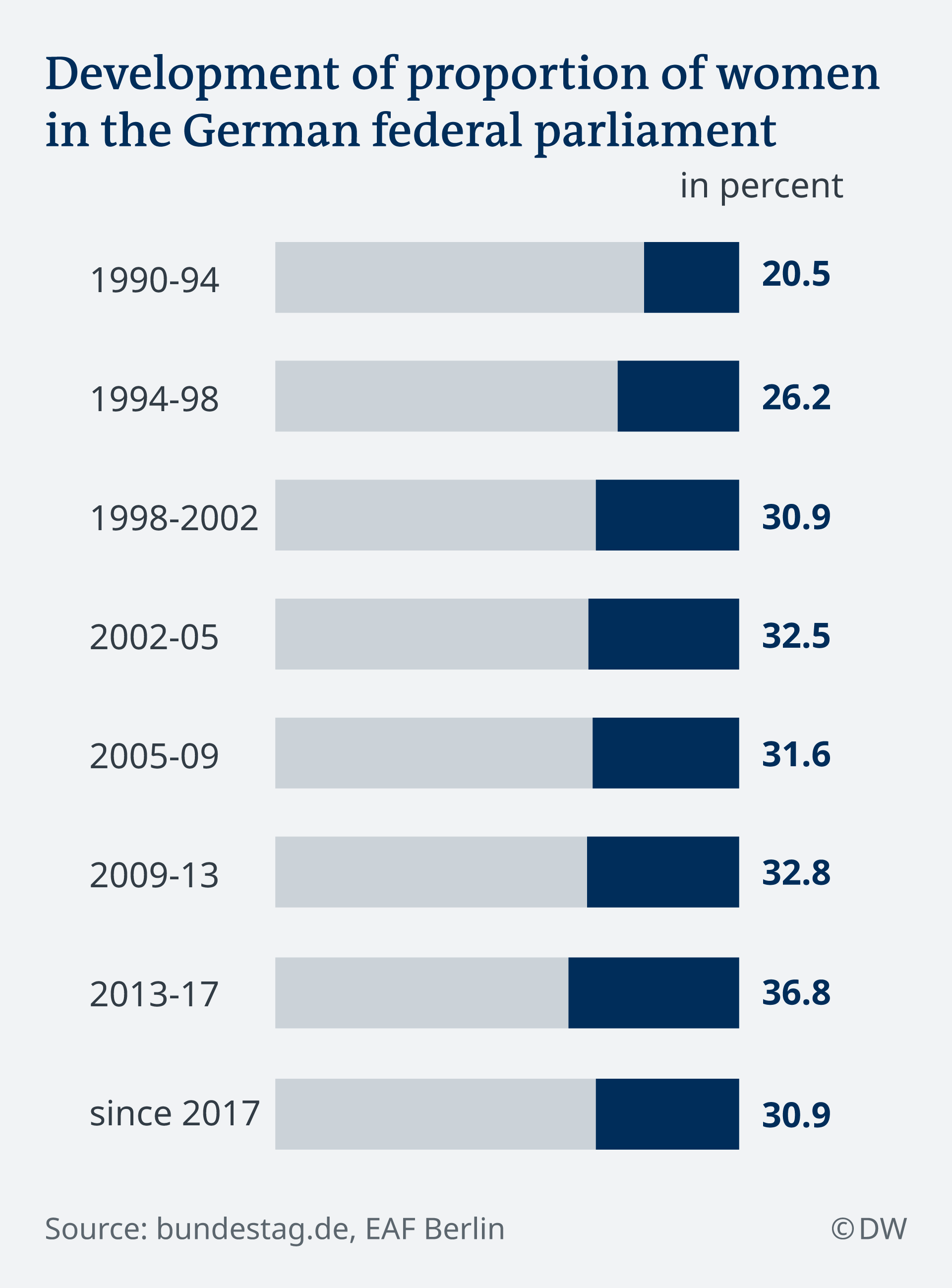

Though the country’s early efforts to promote gender equality made it one of the world’s most pioneering when it came to promoting women’s political participation, Germany has today fallen behind in this effort. Compared with other countries, Germany’s share of women in politics is only middling, and the percentage of women in the German Bundestag has reached a 20-year low.

That lack of strong women’s representation in German politics a is indicative of the broader problems of gender equality in the country, too. In other industries and across public life, German women are hindered in reaching high-profile leadership positions.

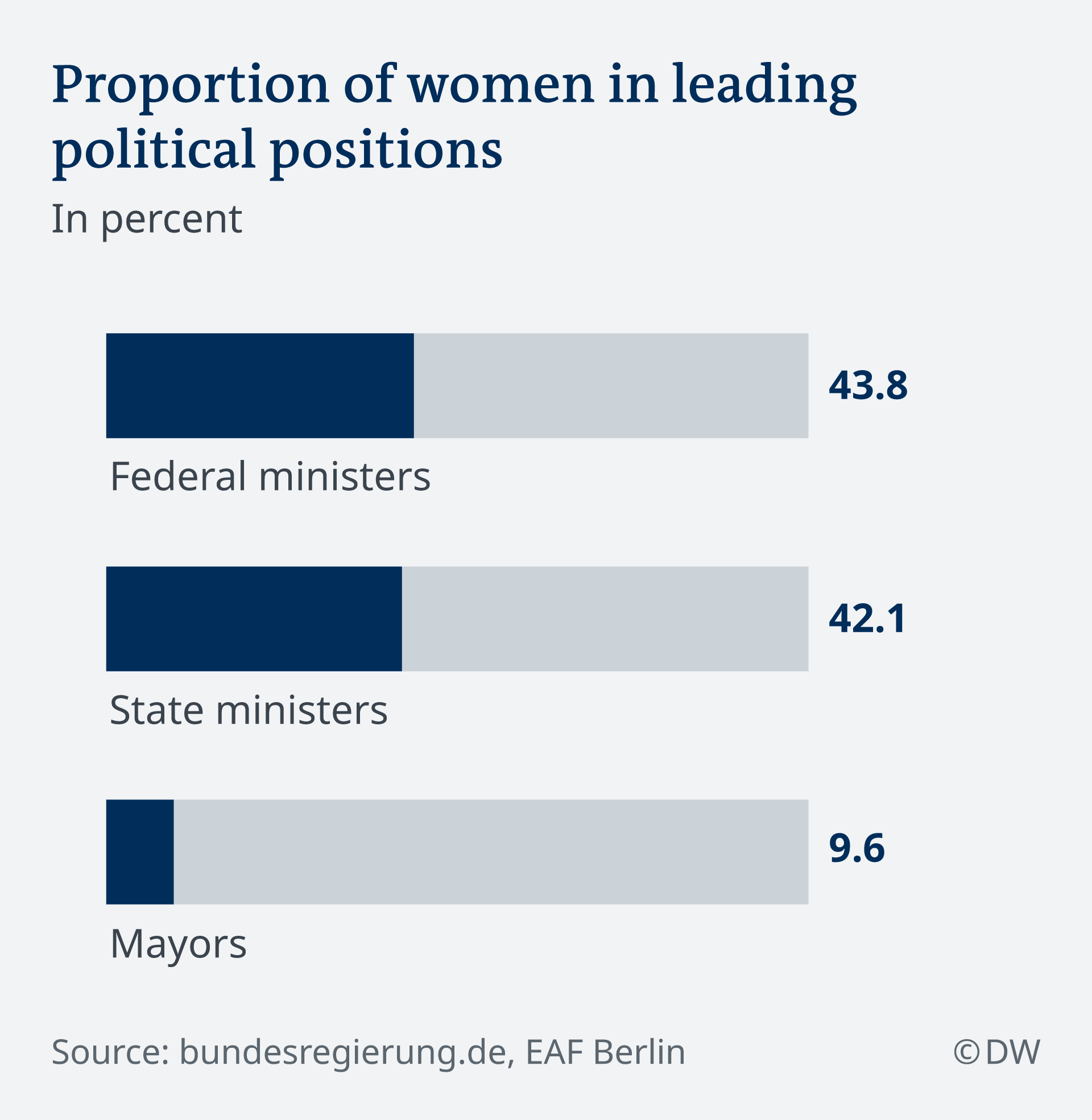

The numbers

In Germany’s lower house of parliament, the Bundestag, the percentage of women actually dropped after the 2017 federal elections: Just 218 of the 709 elected parliamentarians, or 31 percent, are women. This puts Germany in 46th place in the world ranking of female representation (out of 193 countries), trailing 11 other European Union member states, according to statistics from the Inter-Parliamentary Union. The previous German Bundestag, by contrast, included nearly 37 percent female parliamentarians.

Rwanda leads the global ranking with 61.3 percent women in its lower house of parliament. Back in Europe, Sweden, for example, has a parliament comprised of 46 percent women; Finland, Norway, and France all have around or just over 40 percent women.

The drop that occurred in the 2017 elections comes in large part from the two political parties that entered or reentered the Bundestag this time around: the far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD), which gained parliamentary seats for the first time, and the liberal Free Democrats (FDP), which returned after four years out of parliament. Of the AfD’s 92 members, just 11 percent are women; among the FDP’s parliamentary group, 24 percent are women.

Double standards and ingrained thinking

Politics has always been a male-dominated arena, but there are some systemic reasons this remains the case. Women are often asked to explain how they will balance family life and a career in politics — a question that is rarely, if ever, asked of their male counterparts. In addition, fewer women tend to run for political office to begin with. And some female politicians say the large proportion of men in the industry in some ways reinforces itself: They seek out colleagues and potential successors based on who they feel comfortable with or relate to, which often means fellow men.

Katja Dörner, the deputy leader of the Greens’ parliamentary group, said the reasons for such discrepancies are myriad: some of it has to do with ingrained cultural ideas. “And then there’s simply the compatibility of work and public office with family, which is often still difficult on the grassroots level,” she told DW. “But there are also male cliques, cultural influences and the demands made on people in politics.”

Concrete measures

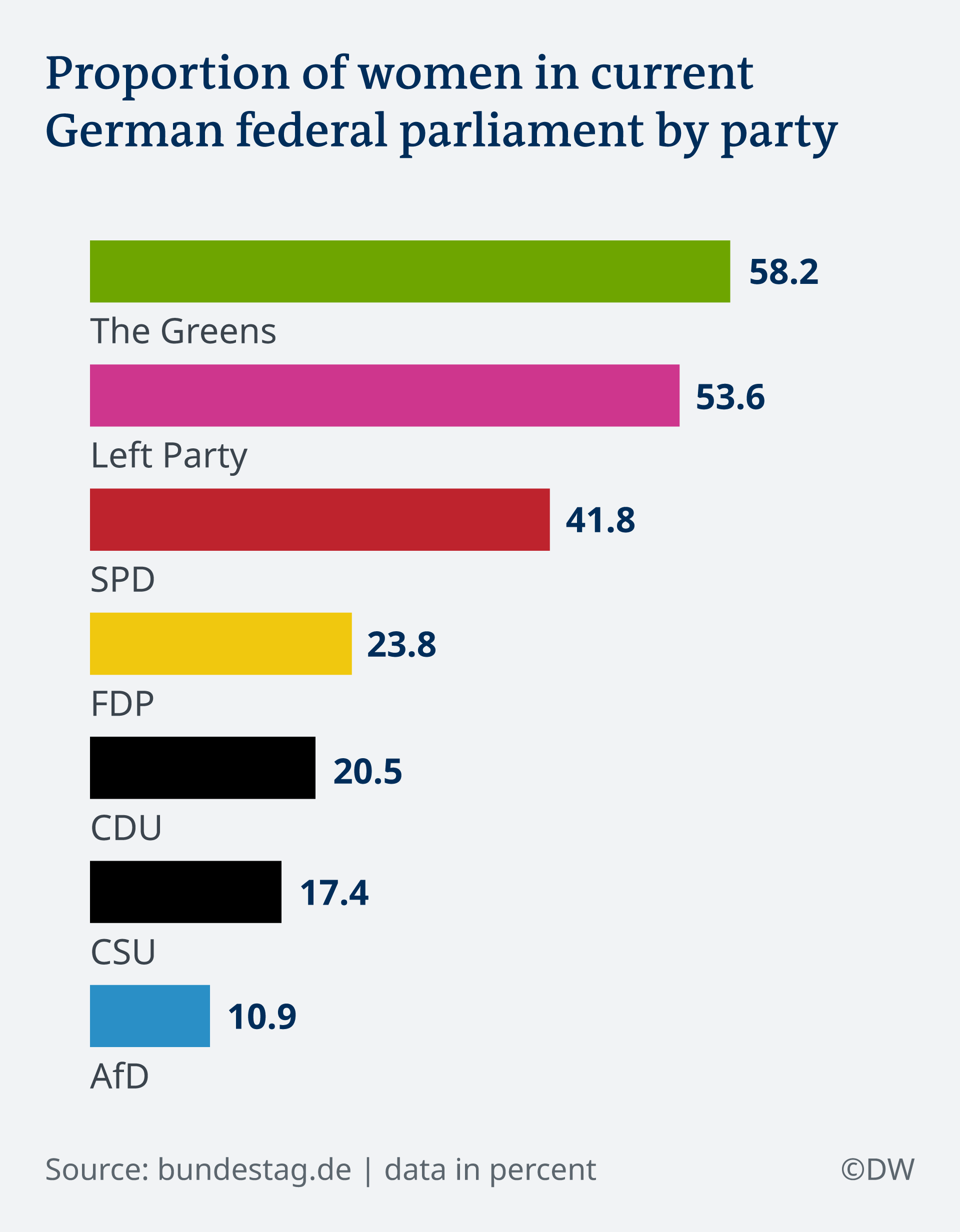

So what can Germany do to involve more women in politics? The parties with the greatest success at electing women, the Greens and the Left party, have one major characteristic in common: They have instituted internal gender quotas for candidates and politicians.

The Greens and the Left party require that 50 percent of all candidates and ministers be women. In the current Bundestag, 58 percent of Greens parliamentarians and 54 percent of Left parliamentarians are women.

The SPD, by contrast, requires 40 percent of candidates and ministers to be women; their parliamentary group currently consists of 42 percent women.

“A quota isn’t a wish or some nice thing, it’s a means to an end,” Dörner said. “And if you don’t reach an important goal, and it’s obvious you won’t reach it, then you need a new, effective tool.”

Quotas still controversial

Other parties have considered quota systems but ultimately not implemented them. Earlier this year, the FDP’s Nicola Beer floated implementing one within her own party; the CDU has a so-called women’s quorum, aiming for 30 percent representation, but it is nonbinding and the party often fails to reach that threshold. According to polls, the German electorate is split on whether such measures should be implemented.

With Germany set to celebrate the centennial of women’s voting rights here, it’s clear the country still has a long way to go when it comes to ensuring that women’s voices are appropriately represented in politics. As Merkel’s time as chancellor comes to a close, this issue — and how exactly to do something about it — is on the minds of many of the country’s advocates for equality.

Author: Emily Schultheis

–