‘Red Rosa’ Luxemburg and the making of a revolutionary icon

Revolutionary socialists Rosa Luxemburg and Karl Liebknecht were executed 100 years ago in Berlin. In the ensuing century, Luxemburg has become a cult figure for the left — and for feminists, artists and pacifists.

On Sunday morning, some 10,000 people braved the rain and cold to march through eastern Berlin and place red carnations at the graves of Rosa Luxemburg and her comrade, Karl Liebknecht.

The march was commemorating 100 years since the brutal execution of the two revolutionary socialists on January 15, 1919.

In the ensuing century, this diminutive Polish-born Jewish intellectual with a limp has become a cult icon for the revolutionary left. Yet she has also had a broader appeal, admired by feminists, socialists and pacifists.

She has become part of Germany’s cultural memory, immortalized in art, poetry, an award-winning biopic, a musical and a graphic novel. And in her own words too: as well as being a brilliant Marxist theorist, Luxemburg was a prolific writer of letters, and her emotive, lyrical writing has seen her emerge as a literary figure in her own right.

‘Those who do not move, do not notice their chains’

Luxemburg, who as a teenager fled Russian-occupied Poland due to her socialist activities, first attained her doctorate in Zurich before arriving in Berlin in 1898. She quickly rose through the ranks of the Social Democratic Party, the biggest labor movement in Europe at the time. Yet she broke with the SPD due to its support for World War I in 1914, helped form the breakaway Spartacist League in 1916 and spent most of the war in prison.

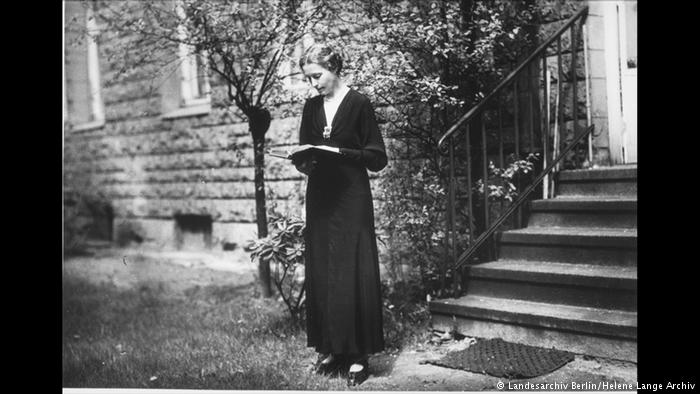

Luxemburg and Liebknecht are commemorated every year on the second Sunday of January

In November 1918, a revolt by sailors and soldiers led to the overthrow of the Hohenzollern monarchy and the end of the war. In December, the Spartacist League renamed itself the German Communist Party (KPD) and Luxemburg asserted that they would not try to seize power without the support of the majority of Germans. Yet when a second revolt broke out on January 5, 1919, she and Liebknecht gave the movement their full support. The uprising quickly faltered and the SPD leadership ordered the army and right-wing paramilitaries, the Freikorps, to crush it.

On the night of January 15, Luxemburg and Liebknecht were abducted, tortured in the luxury Hotel Eden, and then driven separately to the nearby Tiergarten Park and murdered. Liebknecht was delivered to the city morgue while Luxemburg was dumped into a canal.

Her body was only recovered five months later after the winter ice had thawed. She was buried next to Liebknecht in the Friedrichsfelde Cemetery.

Creation of a myth

Much of Luxemburg’s subsequent fame derives from this brutal murder, argues Mark Jones, a historian and writer of Founding Weimar. Violence and the German Revolution of 1918-1919.

“The destruction of the female body, the intense violence against it and the absence of any traditional kind of mourning leaves this trauma which impregnates German cultural thought about Rosa Luxemburg for the next 100 years,” he said.

The murder deeply divided the political left, something that undoubtedly contributed to the end of the Weimar Republic and the rise of the Nazis. As a result, after World War II, there was speculation about whether the Third Reich and the Holocaust could have been avoided had Luxemburg survived. She became a hugely popular figure for the radical student movement of 1968 and her opposition to World War I also resonated with the peace movement of the 1980s.

After the January 1988 march, several critics of the GDR regime were arrested for showing a banner with Luxemburg’s famous quote

Meanwhile, the murder of “Rosa and Karl” was one of the key foundation myths of the East German state, said Jones.

However, though East Germany celebrated her as a martyr, it did not embrace Luxemburg’s political thought, particularly her criticism of Lenin and the Russian Bolsheviks’ putschist strategy and terror.

And as dissent in the later years of the GDR grew, some marchers in January 1988 carried her words “Freedom is always the freedom of those who think differently” aloft, a deliberate rebuke of the totalitarian regime.

Yet Jones argues that some of the hagiography surrounding Luxemburg often omits the fact that she did end up supporting political violence in January 1919. “People forget that before she was killed, when the violence of the second uprising was ongoing, she was publishing articles and a newspaper which called on workers to join in the armed struggle and to overthrow the state,” he said, adding that she rejected the option of a negotiated surrender even though the uprising was clearly failing and many civilians were being killed.

Artistic representations of a ‘badass revolutionary’

Nonetheless, Luxemburg’s brutal killing ended up having a great cultural impact. Soon after her murder in 1919, artist Max Beckmann produced a series of lithographs, Die Hölle (Hell), which graphically depicted her murder, while a drawing by left-wing artist George Grosz showed justice as a ghost trailing a bloodstained robe across the open coffins of the two victims. In 1929, Bertolt Brecht wrote a commemorative poem, “Epitaph,” to mark the 10th anniversary of her death.

Architect Ludwig Mies van der Rohe designed a monument to Liebknecht and Luxemburg, which was built in the Friedrichsfelde Cemetery in 1926. But the Nazis reviled Luxemburg, and the monument was razed to the ground in 1935.

Kate Evans revisits Luxemburg’s life in her graphic novel

Following World War II, Luxemburg’s death continued to resonate. A 1960 painting by American artist R.B. Kitaj, The Murder of Rosa Luxemburg, the 1978 play Germania: Tod in Berlin by Heiner Müller, and works by artists and writers connected with the women’s movement, such as Americans May Stevens, Jane Cooper and Donna Blue Lachman, all grappled with her life and murder.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder was planning a film about her when he died in 1982. A few years later, Rosa Luxemburg, directed by Margarethe von Trotta, won Barbara Sukowa the best actress prize at Cannes in 1986. The film was regarded as a feminist retelling of her story as a liberated woman, though Luxemburg herself had little interest in organized feminism.

More recently, the musical Rosa premiered at Berlin’s Grips Theater in late 2008, and in 2015 the British graphic novelist and activist Kate Evans depicted her story and political thought in her biography Red Rosa.

For Evans, it was important to go back to the political writings to counteract the “sentimentalization” of Luxemburg as a “sensitive, poetic flower.” In fact, said Evans, “she is a badass revolutionary, who is quite bristly and extremely forthright and dedicated in her views, an incredibly towering intellect.”

“Concentrating on her poetry or concentrating on her death, you are not giving true credence to her life,” she said. For Evans, it’s natural that so many people read different things into Luxemburg. “It’s the mark of someone who has left an interesting and complete body of work.”

Author: Siobhán Dowling

–