Survivors of domestic violence are portrayed by a powerful collection (I)

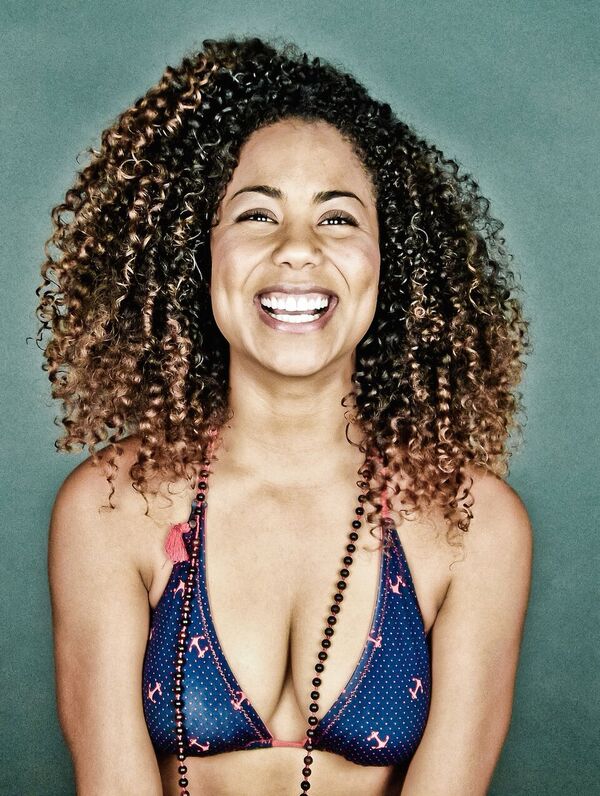

Rebekah Trachsel, Credit: Unconventional Apology Project

Chantal Barlow is the initiator of Unconventional Apology Project. It’s about the powerful women who speak out against domestic violence. Read our interview with Chantal and find out what moved her to set up her unusual project.

When did you decide to create this collection of portraits?

I started the Unconventional Apology Project after I inherited my grandfather’s cherished camera when he passed away in 2013. As an artist, I always focus on challenging myself and swimming upstream, taking the time to look at the familiar in an unfamiliar way and taking what I can from this experience. I knew I had to do something powerful with my grandfather’s camera.

He was a man of minimal means and was known for taking pictures of the family as we grew older. I found out about him murdering my grandmother when I was 16 – until then I had only known him as a loving grandfather. I started the project as a way to not only honor my grandmother and bring her to the forefront, but also to provide a safe space and a platform for healing and compassion through storytelling. I honor my grandmother through the number of portraits (36 in honor of her age when she was killed) and by using her favorite color – blue. That’s why all the participants wear blue. I wanted to show that survivors can still live a life full of light and hope and I felt examples of triumphant survivors were missing from the global discussion on domestic violence. I intentionally created the project to be survivor-centric, involving survivors and putting them first.

How did you find the women?

Initially, the project featured a couple of people I knew personally, but when I shared my own story, people I didn’t know contacted me via my website and social media. What began as a local project for Los Angeles (all the photo shoots are done here since the project is mostly self-funded) expanded to include participants from around the country who were willing to travel to LA to tell their stories. It is powerful for people to see or hear about the project and be moved to want to share their own stories. The pure intentions are evident, which comes across in the interviews. It’s really been a humbling experience and confirms that this platform was desperately needed.

In honor of her mother, Inga Coffee, Ashley Jones. Credit: Unconventional Apology Project

Why are these women willing to tell their history? Do you think that the project can help them?

I think it is always impactful to experience being listened to, respected and supported. They are boldly coming forward to educate others, share their own stories, and impact others’ lives. I’ve learned so much about these amazing people and the interviews serve as an example of what can happen when you are able to release something painful in a safe environment. Healing and hope are possible. It takes nothing to offer those moments to others in your own lives.

Some participants have told us that the project fills a void in terms of presenting survivors in a positive light and allowing them to speak on their own terms, without condensing their statements into sound bites. I took great care of developing the interview questions themselves to allow the participants to share their whole selves, and not just how they were abused. They are more than that experience. I believe that the light you see in their portraits comes from being free from abuse, and having a platform to release the burden of shame, guilt and embarrassment. My focus was to show them as beacons of hope that there is life after abuse. Moving through and past abuse is not about no longer being emotional, it is about understanding what a healthy relationship is, having self-confidence and self-worth, and holding others accountable for how they treat you – knowing you deserve better and changing your circumstance when a relationship does not reflect the value you hold for yourself. I felt that was one of the most important messages I could convey with this project. Again, this project being survivor-centric is key.

I think the way in which each participant is presented shows that they are joining a community of survivors; strong human beings who have been through so much, but have found their own ways to triumph. Some participants shared that they feel honored to be among the group of women who have come forward to date and want to contribute to the story-telling of the realities of domestic violence, and the realities of leading a life worth living after being free from abuse. We also hear that they have a lot of trust in us to take care of their voices. We take that very seriously, which is why we allow each participant to respond to each question until they’ve said all they want to say about their experience: who they are, how they love and how they’ve grown. We do our best to honor who we meet in that room so that they are proud of their contribution and continue to feel like they did what was best for them and their healing in that moment in time.

Chantal Barlow. Credit: Unconventional Apology Project

Why do you think there is so much violence against women?

There is an unfortunate tendency to seek control of easy targets when you can’t control other parts of your life. Many traditions (cultural, religious, gender-based, power-based, etc.) include dominance over women as formal tenets, so reducing the occurrences of violence against women has to include undercutting the rhetoric that supports it. As with anything that needs to be confronted and uncomfortable in order to shift, it has to be a conscious effort to face what has been communicated explicitly and implicitly throughout a lifetime and through multiple generations.

Do you think that violence within relationships is still a taboo?

I do believe it is still taboo to speak about violence in relationships publicly because of the stigma and judgment people receive when they share that they’ve experienced domestic violence. Part of why I am proud of the diversity of the participants is that it shows the breadth of the impact of domestic violence. Whether or not you know them, they feel familiar. Their faces, smiles, manner of speech and personality in the interviews makes it more difficult to put their faces and experiences aside. They look like your neighbors, friends, relatives, colleagues and any other people you interact with in your daily life. We want to make it hard to look away and dismiss the experience as happening to people who are unfamiliar and who are somehow solely responsible for being mistreated by an intimate partner.

Interview: Delia Friess

Editor: Marjory Linardy

_____

Need a license to rape? Just get married in India!

It’s official! Under Indian law, marital rape cannot be classified as a crime. A 31-member committee including two female members took the Anti-Rape bill to Parliament. (From June 6, 2015)

The Silent Screams…

Today, I’m in peace but there was once when my sealed lips and tear-filled eyes pleaded for mercy. My silence questioned my worth, ‘Am I a piece of land sought to be used for purpose?’ My questions remained unrequited and I deceased to peace. You know, who am I? I am the one with sparkling eyes and babyish look, an eight-year-old girl who perished in urine rupture and internal bleeding on being married to a 40-year-old man. I am a victim of child bride. (From January 8, 2015)

Violence against women in Pakistan often met with ‘state inaction’

Eight years into Pakistan’s democratic transition, violence against women is still endemic, a new ICG report found. The group’s Samina Ahmed talks about why biased attitudes towards women lie at the heart of the problem. (From April 9, 2015)