An archaeology of erotica

The monstrous feminine: a vessel for male pleasures, her “promiscuity” often cited as a symptom of feminine malaise and corruption. This hypersexualisation of the Oriental female was used as a rhetorical strategy to heighten the nature of her angelic nature of her Occidental counterpart.

Nowadays credited to a fifteenth-century Egyptian polymath called Jalal adʹDin al-Suyuti, “The Book of Exposition” is an exploration of promiscuity under the societal constraints of the Arab-Islamic world, using bawdy and salacious scenarios to stimulate and evoke fantasies in the readerʹs mind.

A decade or so after famed Orientalist Richard Burton translated Muhammad ibn Muhammad al-Nafzawiʹs The Perfumed Garden of Sensual Delight (1886), an anonymous translator became the first to critically assess and introduce for Anglophone audiences another Middle Eastern controversial and enigmatic text – Kitab al-Izah Fiʹilm al-Nikah b-it-Tamam w-al-Kamal, orThe Book of Exposition – a collection of fifteenth-century erotica.

Despite there being much dispute over the authorship of the work, from both Western and Middle Eastern scholars over the centuries, The Book of Exposition is nowadays credited to a fifteenth-century Egyptian polymath called Jalal adʹDin al-Suyuti (1445-1505). Although perhaps best known for his co-authorship of Tafsir al-Jalalayn (Tafsir of the Two Jalals), a classical Sunni exegesis of the Koran, al-Suyuti was also a prolific erotologist, writing at least twenty-three treatises on various aspects of the sexual arts.

The two dozen stories he presents in The Book of Exposition are an exploration of promiscuity under the societal constraints of the Arab-Islamic world, using bawdy and salacious scenarios to stimulate and evoke fantasies in the readerʹs mind. Explicit and vulgar in parts, stories like “The Strange Transformation that Befell a Certain Believerʹs Prickle” explore the sexual taboos of Islamic culture.

In this tale, a man prays to Allah to cure his erectile dysfunction, a wish he is granted. But when his wife is confronted with his new prowess on the “Night of Power” (Lalyat al-Qadr), she instantly tells him that “if thy weapon so continueth, you must pronounce against me the words of the divorce, and let me go free,” due to his penis now being “as straight as a column which would neither display suppleness, nor show itself capable of the power of elasticity and movement, nor of rest.” Needless to say, the man failed to profit on the Night of Power.

Fifteenth century “sexploitation”

Other stories like “The Pious Woman & What Happened to Her From Behind” are rather unambiguous in their content. The offerings vary in length, from a few sentences to a few pages, but all clearly stem from a sexually liberated mind. Set within largely prosaic domestic and social settings, the stories are akin to the British sexploitation movies of the 1960s and 70s, which allowed the public to visualise everyday sexual encounters; only here the amorous milkman and window cleaner are replaced by the olive oil seller, prostitute and peasant.

In a run of just three hundred copies, the translator – known only as “An English Bohemian” – sought to critically assess and place the work in its historical and literary context. In addition to an extensive foreword, the edition also includes an expansive section entitled “Excurses”, which offers up appendices of other short erotica, notes and observations, including an essay by Richard Burton on pederasty (featured also in his 1885 translation of Arabian Nights).

This edition of The Book of Exposition was first published in the midst of the Belle Epoque; a period wedged between the end of the Franco-Prussian War (1871) and the beginning of World War I (1914). France, and Western Europe more broadly, was brimming with optimism, and pan-European ideals were sweeping over the continent. Attitudes towards sex, however, remained relatively conservative.

Sexuality was curbed and ridden with guilt – masturbation was believed to harm oneʹs physical and mental wellbeing and intercourse was generally spoken of as a clinical act that should never stray down any peculiar paths. A prominent idea was that male ejaculation outside of marital sex was caused by “spermatorrhea”; those who were diagnosed were forced to be circumcised, castrated, or wear a chastity belt, a sort of deranged piece of armour for the penis only.

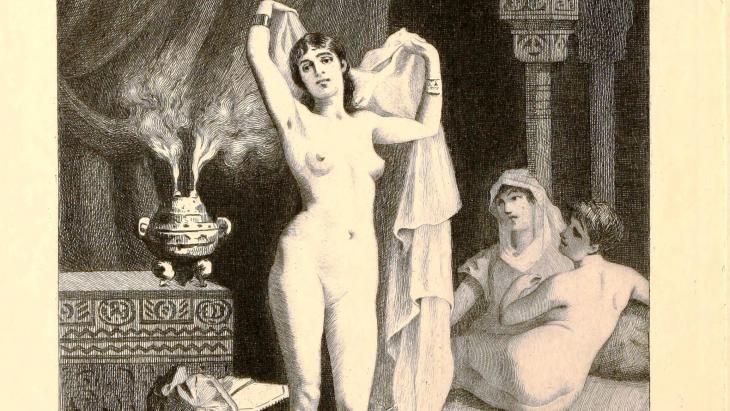

Polarisation of female sexuality

Female sexuality tended to be polarised: either angelic or monstrous. The frailty and purity of the Victorian woman was sanctified in the cliche of “The Angel of the House”, an image popularised in Coventry Patmoreʹs 1854 narrative poem of the same title. The domestic feminine was placed on a pedestal and her sexuality was pragmatic.

The monstrous feminine, on the other hand, was a vessel for male pleasures, her “promiscuity” often cited as a symptom of feminine malaise and corruption. This hypersexualisation of the Oriental female was used as a rhetorical strategy to heighten the nature of her angelic nature of her Occidental counterpart.

In his seminal book Orientalism (1979), Edward Said repudiates the aforementioned authors for establishing the foundations of the damaging East/West cultural binary.

Europe, according to Said, was suffering from “increasingembourgeoisement“, referring to the institutionalisation of sex; the Orient, on the other hand, had apparently become a place where one could seek out libertine sexual experiences denied in Europe.

In his opening essay and commentary, An English Bohemian sets up “Oriental Sexuology” as a mystical alternative for aspiring libertines/hedonists. In the process, he makes some incredibly bold claims; so bold, in fact, as to cast some doubt on their validity.

The sexual mores of the Belle Epoque: “Europe, according to Said, was suffering from “increasing embourgeoisement”, referring to the institutionalisation of sex; the Orient, on the other hand, had apparently become a place where one could seek out libertine sexual experiences denied in Europe,” writes Dhaimish

He compares – or rather polarises – the East and Westʹs attitudes to sex and marriage, including polygamy: “So far from the harem being a prison to the wives, it is a place of liberty, where the husband himself is treated as an interloper”, concluding that it empowers and liberates women and is not the “extinguisher of love” that it is perceived to be in the West, nor should it be associated with a regressive mindset.

Personal cultural rebellion

However, it is hard to tell whether he truly believes his own assertions, which, at times, in their elevation of Orient over the Occident, appear to be motivated more by a desire to rebel against the prevailing establishment of his own culture, than to offer a nuanced picture of a foreign culture.

An English Bohemian doesnʹt just limit himself to the Orient in his examination of sexuality. He offers an insight into the sexual customs of other lands he claims to have travelled and researched extensively as a former practitioner of medicine: from Loango to the Aztecs, Paraguay to Samoa, Europe to Arabia, he describes the diversity of meanings attached to a womanʹs loss of virginity. The mixed methodology applied to obtaining such data may appear outdated today, but his conclusion is strikingly contemporary:

If only in the choice of their lifeʹs companion men laid more stress on virginity of heart and purity of soul, instead of looking with so much ill-applied curiosity for the blood-stain on sheets or underclothing, how much fewer disillusions they would find in marriage, and much more true happiness!

An English Bohemian was drawn to the Orient from the alluring texts that he was so fond of, which inevitably resulted in him translating The Book of Exposition, despite it being little more than a collection of risque stories. Irrespective of its introduction, copious footnotes or the collectionʹs own independent value to the critic, The Book of Exposition remains one of the finest literary examples of the absurdity behind what was once a burgeoning, yet very problematic field of study.

Author: Sherif Dhaimish

Qantara.de 2018