When women ruled the Muslim world

Were it not for the timely intervention of women down the centuries, many an Islamic dynasty would have torn itself apart.

The ancient East knew many female leaders who were successful rulers of kingdoms, yet authority in the Islamic world was the exclusive preserve of men. Sons, brothers and grandsons were the only ones with a recognised right to inherit power. Nevertheless, Islamic history is riddled with severe crises that threatened to destroy a number of dynasties had it not been for the intervention of women, who assumed guardianship of the young caliphs and kings as a way of protecting the caliphate and realising their own ambitions of power.

So how were these women able to scale the ladder – commanding armies, running states and kingdoms – in the face of cruelty, tyranny and violence?

Al-Khayzuran: the power to defy history

None of the women of the Abbasid caliphate have gone down in history quite like Al-Khayzuran bint Atta, wife to Caliph Al-Mahdi and mother to the caliphs Al-Hadi and Harun al-Rashid.

Originally, Al-Khayzuran – of Yemeni descent – was brought to Baghdad as a slave. She captured the heart of the Caliph Al-Mahdi, who broke all conventions of the Abbasid dynasty by freeing her and making her his wife.

She was known for the visible role she played in various aspects of running the caliphate. Supported by her husband′s high regard for her, she was consistently involved in politics and decision-making.

In his book History of the Prophets and Kings, Al-Tabari describes her as a woman who controlled her son, pushing him along the same path as “his father… the tyrant who ruled with order and strength.” Historians view her relationship with her son as problematic. It is said that Al-Hadi asked her to stop interfering and spend the rest of her life praying.

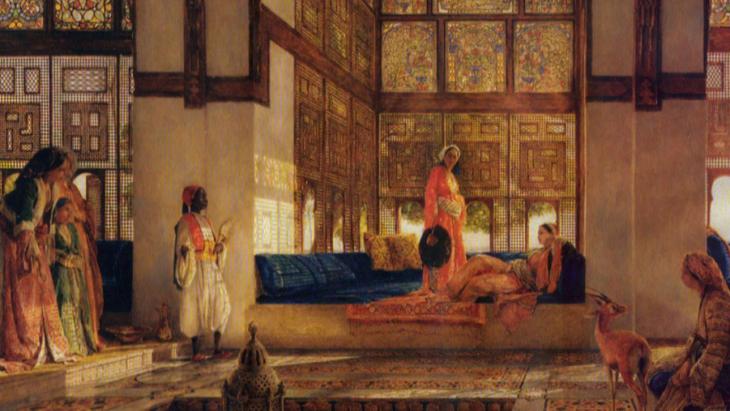

Beloved of the Caliph: the silver casket illustrated above was the ruler’s gift to Subh on the birth of their first son in 966. She was destined to play an active role in affairs of state and on the death of her husband, became one of three guardians entrusted with holding the throne for his son and heir, Hisham II.

Stories tell of her attachment to power; it was rumoured that she was the one to plot the assassination of her son when he fell ill. Al-Tabari records that Al-Hadi′s death was his mother′s fault; she it was who ordered one of her slave-girls to suffocate him in his bed.

Once the caliphate had sworn allegiance to her younger son Harun al-Rashid, the position of Al-Khayzuran was strengthened yet again and her rule continued until her death in 789 AD, two years after the death of her son Al-Hadi.

Subh of Cordoba: The Basque who ruled Cordoba

In Cordoba, capital of Andalusia under the Umayyad Caliphate, a girl from the Basque region, north of the Iberian Peninsula, ascended to the highest circles of influence. She was called Aurora, but in Cordoba, she was known as Subh the Basque.

Subh was brought from northern Spain to Andalusia as a slave and was sold more than once before she came to the attention of Crown Prince Al-Mustansir al-Hakam, one of the strongest rulers in tenth century Europe.

Al-Hakam was impressed by Subh, so he bought her and she became the closest person to his heart, especially after giving birth to his son, Hisham II Al-Mu′ayed.

After the death of ′Abd al-Raḥman III and the succession of his son Al-Mustansir to the throne of the Caliphate in 961 AD, Subh entered the corridors of power and she played an active role in affairs of state, not to mention a number of political disputes.

However, it was to be her husband′s death that catapulted Subh to power. Al-Hakam had thought to appoint a tripartite guardianship over his son and heir, Hisham II, who was only a toddler when al-Hakam′s died.

The three regents were First Minister Jafar al-Mushafi, Chamberlain Al-Mansur Ibn Abi Aamir and Subh. It was only a matter of time before rivalries and alliances began to arise between the three regents. Yet, Al-Hakam′s choice of Subh as the guardian of their son attests to the Caliph′s confidence in her and her political acumen.

Subh sought an alliance with Abi Aamir. Having managed to eliminate any influence exercised by the first minister, they ruled Andalusia together for a few years, until renewed disputes arose, which led to her exclusion as regent. Abi Aamir subsequently deposed Hisham II and confined him with Subh at their palace in the city of Azahra.

Despite this, Subh continued plotting and working on ways to restore her son to the throne until her death.

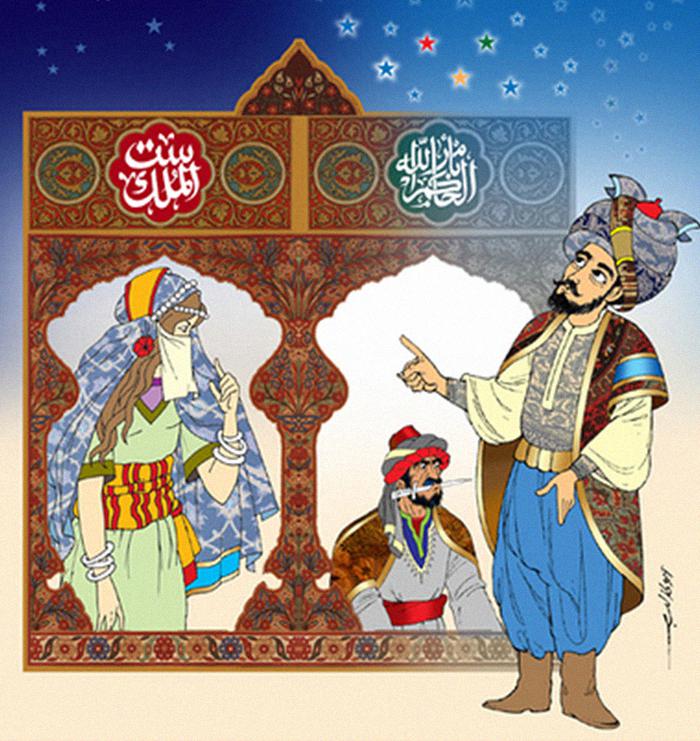

A consummate survivor: Sitt al-Mulk, who was encouraged by her father, Fatimid caliph Nizar al-Aziz Billah, to become involved with politics, was to see off a number of power-hungry opponents, including her brother, who disappeared in mysterious circumstances. She retained control of the Fatimid empire until her death in 1023.

Sitt al-Mulk: an iron fist

The Fatimid dynasty witnessed the emergence of a number of women who spearheaded political action and exercised power.

One of the most prominent and most successful among them was Princess Sitt al-Mulk, born in 970 AD, who was the daughter of the fifth Fatimid Caliph Nizar al-Aziz Billah.

Her involvement in politics began during her father′s reign when he recognised her intelligence and wisdom. He brought her closer to the upper echelons of his government and was always keen to consult with her on matters of state.

After the death of her father and the succession of her younger brother, Al-Hakim bi-Amr Allah, Sitt al-Mulk took over the reigns of government and had the upper hand when it came to decision-making. She shared power with Minister Barjuwan, who at the time was the caliphate′s de facto ruler.

Historians recount that Sitt al-Mulk was not on friendly terms with her brother, who effectively excluded her, limiting her involvement in politics. Most historians, however, indicate that she was able to regain control of state affairs again by 1021 AD.

A number of historians, including Taqi al-Din al-Maqrizi, in his book Ette′aaz al-honafa be Akhbaar al-A′emma Al Fatemeyyeen Al Kholafaa, also mention that Sitt al-Mulk plotted with some of her allies to kill her brother and spread rumours among his followers that he had disappeared.

After the disappearance of Al-Hakim, the caliphate swore allegiance to his son, Az-Zahir li A′zaz li Din-illah, who was still only 16 years old. Because of his tender age, Sitt al-Mulk yet again assumed the responsibility of ruling the caliphate and her decisions were the final word. She managed all state affairs firmly and remained on the throne until her death in 1023 AD.

The mother of Al-Mustansir Billah

If Sitt al-Mulk was a model for a successful Fatimid woman in the political field, the mother of the Caliph Al-Mustansir was her antithesis; a woman who – faced with harsh circumstances that almost led to the destruction of the caliphate – has become synonymous with failure.

In 1035 AD, the Fatimid Caliph Az-Zahir li A′zaz li Din-illah died and his son, Abu Tamim Ma′ad al-Mustansir Billah, was instated as caliph. Since Al-Mustansir was not even seven years old, his mother was his guardian until he reached adulthood.

It is odd that despite all the power and influence that she exercised, we hardly find her name mentioned in the historical texts of the Fatimid era; all of the sources refer to her solely as the mother of Al-Mustansir, without a name or a distinctive title.

“The hard years of al-Mustansir”: in-fighting between different national factions coupled with seven years of drought and famine brought the powerful Fatimid dynasty to its knees.

In the early period of her rule, the Fatimid state extended its sphere of influence to include numerous countries and regions. The empire included Egypt, South of the Levant, North Africa, Sicily, the Red Sea and the countries of Hejaz and Yemen.

As the years went by, however, the tide began to turn.

According to Ibn al-Athir′s Al-Kamil fi al-tarikh (The Complete History), the mother of Al-Mustansir was of Sudanese origin. She sought to raise the status of Sudanese soldiers who were an integral part of the Fatimid army ranks in Egypt. In doing so, she aimed to protect her rule and to create a counterbalance that would limit the power of the Moroccan and Turkish soldiers, who represented the main and fundamental force in the caliphate.

This triggered civil war between the different sections of the Fatimid army and the state deteriorated as a result. The conflict took place as a seven year period of famine and drought laid waste to the empire. The economic consequences in Egypt were dire – and are described by historians as “Al-Shidda al-Mustansiriya” (the hard years of al-Mustansir).

As for the mother of Al-Mustansir, some historians like Ibn Taghribirdi and Al-Maqrizi mention that she had left for Baghdad with her daughters during the famine years. She left her son, the young caliph, behind, hoping he would salvage his rule in Cairo.

Terken Khatun: the Empress

Empress Terken Khatun was one of the few women who to play an active role in politics during the Seljuk era. Most notoriously, her name is associated with the assassination of Vizier Nizam al-Mulk.

In 1092 AD, a young Sufi assassinated the great Seljuk vizier. Although the assassination of the minister is known to have been orchestrated by Hassan-i-Sabbah, the leader of the notorious Hashshashin (Assassins) group, a number of historians such as Ibn al-Jawzi and Al-Dhahabi are clear in attributing responsibility for the assassination to the Empress.

It is known that Terken Khatun was deeply involved in the political affairs of the state. When her husband, Sultan Malik Shah I, passed away, she competed with the vizier for influence over the throne.

At the time Terken Khatun was working to ensure the succession of her own younger son, Mahmud, while Nizam al-Mulk backed Barkiyaruq, the eldest son of Malik Shah – dispute between the Empress and the vizier was inevitable.

An agent or “fida’i” of the Ismailis (“Order of Assassins”), on the left wearing a white turban, fatally stabs Nizam al-Mulk, the Seljuk vizier, in 1092. But why are female guardians portrayed as being directly responsible for the assassination of their rivals? Was this too part of the power struggle? Or was it a pattern of narrative that chroniclers resorted to in order to frame power in the hands of women as something unearned or unacceptable?

With the death of Nizam al-Mulk, the path was cleared for the empress and after the death of her husband, their young son Mahmud, who was only four years old, assumed the throne. As her son′s guardian, Terken Khatun attempted to assert her authority over the state as regent.

Her reign was to be short-lived: the eldest son Barkiyaruq quickly rebelled, reclaiming the Seljuk throne for himself, ousting his younger brother and putting an end to the empress′s ambitions for power.

Female guardians in the historical sources

Since most accounts of the caliphate were documented from the viewpoint of chroniclers, it is necessary to comment on their accounts of women rulers in Islamic history.

Firstly, we often find female guardians portrayed as being directly responsible for the assassination of their rivals.

This begs the question: was this too part of the power struggle? Or was it a pattern of narrative that chroniclers resorted to in order to frame power in the hands of women as something unearned or unacceptable?

The latter tendency can be seen in the terminology used to discuss the validity of the guardians′ rule, as they often describe women′s roles in politics to be “interference” or “seizure”, despite the fact that these guardians also had experience and political acumen, not to mention strong personalities – all qualities necessary for successful governance and state leadership.

And finally, even when the achievements of these women brought power and prosperity to the caliphate, the historical sources rarely credit them with such.

Author: Mohamed Yosri