Bonington: “The joy of climbing in the Himalayas is exploration”

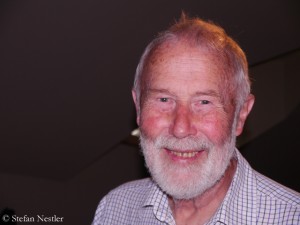

He was knighted to Sir Chris Bonington but he kept his feet on the ground. The 80-year-old Briton, a true living legend in mountaineering, is still a friendly man who is always speaking frankly. I was able to verify this at first hand when I met him last week in Chamonix where he was awarded the Piolet d’Or for his life achievements in the mountains.

Chris, what does the “Career Piolet d’Or” mean to you?

It means a huge amount, because this is an award for my peer group. And in it I’m joining some of the finest and best climbers in the world [Walter Bonatti (awarded in 2010), Reinhold Messner (2011), Doug Scott (2011), Robert Paragot (2012), KurtDiemberger (2013), John Roskelley (2014)], many of whom of course are good friends as well. So it means as much as any award I ever had.

You are 80 years old and you are still climbing, most recently in Catalonia in Spain some weeks ago. Please tell me your secret?

I am climbing very modestly. And I think it’s because I always kept climbing. I think, this is the secret, for everyone. You actually see now more and more grey hairs climbing walls in the mountains and hills. My standard steadily drops, but that doesn’t matter. I still love climbing and being out in the outdoors. And I love the companionship with my friends.

Does it become more and more difficult to bring in line your body and mind?

(Laughs) Without a shadow of doubt! The greatest joy of climbing is when you are at the absolute height of your powers and you got all the kind of thrill that a good athlete has, so you got complete command of your body and you are drifting up climbs. As you get older, you creak up them. So that isn’t that kind of physical euphoria. But what there is, is still the love of the mountains. There is the enjoyment of actually being there. And I think you start savoring your friendships even more.

Bonington: Still the love to the mountains

You have done so many extraordinary climbs. What was the most important for you personally?

There is no doubt about it: Annapurna II which was the first Himalayan peak I ever climbed [in 1960], and it’s only a hair’s breath below 8,000 meters [7937 meters]. And in fact it’s a very fine peak, about ten miles as a crow flies from Annapurna I. Inevitably your first ever expedition to the Himalayas is very special. But when it’s such a fine peak and to be able to climb a peak that is only just under 8,000 meters on your very first expedition, that really is something.

Then leading the expedition to the South Face of Annapurna [in 1970] and then to Everest Southwest Face [in 1975], it was a huge organizational role. Certainly the Everest Southwest Face was the greatest intellectual as well as physical challenge that I faced. You are the organizer, the planner, the leader. I do it so because maybe I have a chance to go to the top but that was very low on my priority list.

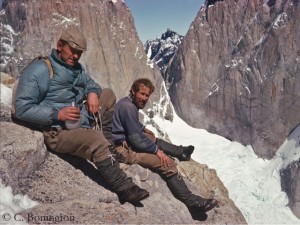

And then just for sheer joy and fun it was a much smaller peak, a mountain called Shivling [in 1983]. I made the first ascent of the West Summit with a great mate of mine, Jim Fotheringham. This was a totally spontaneous ascent. We grabbed the opportunity through getting a free flight to Delhi to take part at a tourism conference and then we went to climb it. It was five days up in Alpine style, one day down, very committing, a beautiful sharp pointed peak. And that to me is what climbing is all about. I was very glad having led my bigger expeditions. In the last 35, 40 years I have really been going for much smaller expeditions, smaller peaks and the whole variety of wonderful adventures.

This year we’ll celebrate the 40th anniversary of the first climb through the Southwest Face of Everest by Doug Scott and Dougal Haston. Back then, in 1975, was it difficult for you not being able to climb because you were the expedition leader?

No, because in a way the expedition was my baby. It was my vision and concept. Then I got together the group of superb climbers to actually complete it. And therefore I had always seen very clearly in my mind that my first priority was the success of the expedition and not just the success of getting to the top of the mountain, but also the success of doing so harmoniously. And from that point of view it was a wonderful expedition. And the only very serious cloud of course was the fact that in the second attempt we lost Mick Burke.

Bonington: The Everest Southwest Face Expedition was my baby

Till now there are only a few other routes through the Southwest Face of Everest – maybe because it’s too difficult?

It’s interesting actually. I think in addition to our route there is only the Russian one and one or two smaller variations. But I mean, the obviously challenge that nobody has done is a direttissima. That is to go straight up the middle of the rock band and thus straight up to the summit. The way we did was a bit like the way the North wall of the Eiger was first climbed. We found the easiest way, a kind of “serpentining” our way up the mountain. But still now I think there have been only four ascents even of our route.

Many things have changed on Everest. What do you think about nowadays climbing on Everest?

I mean, thank goodness, I got up it when I did. And also thank goodness that in 1985 when I finally did reach the summit of Everest with a Norwegian team, that was the last year that the Nepalese government only allowed one expedition on a route at a time. That meant, in 1985 we had the Western Cwm to ourselves. It was wonderful. I think now it is an inevitable development. I think you could compare it with the history of Mont Blanc. It seemed as inaccessible in the late 18th century as Everest did to Tenzing Norgay and Edmund Hillary in 1953. Then the natural development is: A first ascent is made. Then other ascents are made. Then there is a commercial opportunity and guides start guiding people up. And very quickly on Mont Blanc you got the situation that the ordinary route was being climbed regularly. And it was inevitable that exactly the same thing would happen on Everest. Whether just how you manage it, is the big problem. At the moment it’s a kind of anarchic situation where these hundreds of people are going for it every year and where is a certain amount of conflict, a lot of perhaps unnecessary deaths. But that, you know, will be sorted out in the fullness of time.

Bonington about nowadays climbing on Everest

If you should give a tip to young climbers, would you say: Don’t go to Everest?

I’d say definitely: Avoid it! I’d say to young climbers: The joy of climbing in the Himalayas is exploration. And of course there are literally thousands of unclimbed peaks in the Himalayas. You are not going to get famous climbing them. The problem is, they haven’t got even names, and they are just spot heights. But you get all the joy of exploration by actually going up the valley where people haven’t climbed before and just find your way up and climb a peak.

You have lost so many friends in the mountains. Are climbers in a way forced to handle death more than other people?

It’s a very dangerous sport. If you have the adrenaline junkies which we are and if you want to take that to the extreme and go out to the outer limits inevitably there is going to be a high casualty rate. And there is a high casualty rate amongst extreme climbers at altitude as there are amongst for instance base jumpers, wingsuit fliers and so on. I think it’s not people who have got a death wish. It’s something that people are turned on by the huge excitement, euphoria of taking your body and yourself to the absolute limit to achieve an objective. I think that is the prize you’ve got to be prepared to pay. We may be selfish, we may be unrealistic, but I think you do need adventurers in the world.

Bonington: You need adventurers

Are you now thinking of your own death more often than in earlier days?

No, I don’t. I think I’m essentially an optimist. I’ve got to be one because there were at least ten times where I shouldn’t have come out of it. I’m not afraid of death, but I love life.