Alex Megos: “Climbing is my way to live my dream”

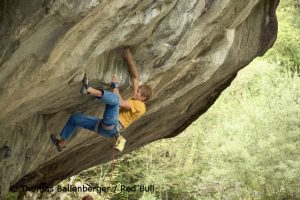

There are people who seem to be able to override the law of gravity. Alex Megos is one of them. The 25-year-old German from the city of Erlangen is one of the best sports climbers in the world. At the age of 19, he was the first in the world to master onsight a route in the Spanish climbing area of Siurana in French grade 9a, which corresponds to eleventh grade according to the classic UIAA difficulty scale. For comparison: Reinhold Messner climbed the seventh degree in his best days. Onsight means that Alex simply climbed straight on without having got any information about the route beforehand. This coup opened the door to professional climbing for him. This spring, Megos added another highlight: He managed the first ascent of the route “Perfecto Mundo” in the climbing area Margalef in the northeast of Spain (see video below showing one of his failed attempts), his first 9b+ (according to UIAA scale a climb in the lower twelfth degree). A single route worldwide is currently considered even more difficult.

I met Alex Megos during the 10th International Mountain Summit (IMS) in Brixen, South Tyrol, where the big names of the mountain scene have been passing the mike to each other for years.

Alex, you are one of only three climbers in the world who have climbed a route with difficulty level 9b+. So you’re right at the front of the pack. How does that feel?

Of course it doesn’t feel so bad. But actually I don’t do it to become famous, but simply because climbing is good for me and because I want to know how difficult I can climb, how far I can push my own limit.

Please explain to a layman what a 9b+ route is like.

It means many, many difficult climbing moves one behind the other in a very steep, partly overhanging rock wall. For example, if someone has a normal door frame of two centimeters, then I can hang on it with one arm. That’s not very difficult. But 9b+ is difficult. (laughs)

What kind of training are you doing?

I actually train every day. About five days a week I go to the climbing wall, the rest of the time I do balance training and other strengthening exercises on the rings, the pull-up bar, the fingerboard, etc.

The Czech Adam Ondra, who has climbed probably the most difficult route worldwide with a 9c, employs his own physiotherapist who shows him new movements that he can integrate into his climbing moves. Do you also have such consultants?

I don’t have my own physio, but I have two trainers, Patrick Matros and Dicki (Ludwig) Korb, with whom I have been working together for twelve years. We analyze together where I can get even better, work on training, invent new exercises. Compared to running or cycling, climbing is still a very young sport, but I think it is much more complex. You have very varied movements, never the same ones. That’s why there are so many different world-class climbers. One is perhaps 1.50 meters tall and weighs 50 kilograms, the other measures 1.85 meters and weighs 80 kilograms. Both are world class, but in different climbing styles. That’s why climbing is so special for me. You just have to find out for yourself where your strengths and weaknesses lie and then work on improving yourself holistically as a climber.

When you climb spectacular routes, the same names always appear in your surroundings: Chris Sharma, Stefano Ghisolfi, Adam Ondra. Is this a small clique in high-end climbing?

Absolutely. We know each other both in rock climbing and in competition climbing. After the two days here at the IMS I will go to Arco to visit Stefano and climb with him. You know each other, you visit each other, you climb together. It is really a small clique.

The mentioned 9b+ route, which you were the first to master, had actually been drilled by Chris Sharma years ago, but he didn’t manage it himself. Does that bother him?

I think he’s out of his age. (laughs) He drilled the route nine or ten years ago, tried it for a few years and failed again and again. Then he turned to another project, the “Dura Dura” route, which four years ago became the world’s first 9b+. He then also climbed it. He was already 33 years old. He became a father, opened a climbing hall and simply had less time. When Stefano (Ghisolfi) and I tried the route in Margalef, it naturally motivated him mega, and he tried it again himself.

You are now 25 years old. Do you already feel at the zenith of your performance?

I definitely don’t see myself at my limit yet. I have found so many weaknesses that I can work on so that I can climb even more difficult things.

There is a 9c route called “Silence” in the cave “Hanshallaren” near Flatanger in Norway, which was first climbed by Adam Ondra in 2017. Doesn’t this extremely overhanging route excite you?

I don’t think this route is ideal for my climbing style. It’s a climb that doesn’t suit me very well. My strengths lie in other climbing fields. If I really want to climb at my limit, then I have to find something that serves my strengths. Only then will I be able to make it.

Whereby Adam Ondra said: If someone can do it, it’s you.

But for that you would have to invest a lot of time. There aren’t that many people who have a) the level to climb something like that and b) also the will to invest so much time. I would rather invest time in something that suits me better.

You originally came from competition climbing.

As a teenager I did many, many competitions, about until I was 18 years old. Then I stopped completely for six years. At the end of 2017, I came back again with some competitions and won again my first World Cup competition in Briancon in France. I would like to get more involved in competition climbing again.

With the long-term goal of Olympia 2020 in Tokyo, where climbing will become an Olympic sport for the first time?

Of course that’s an issue. But I have to think about it carefully, because I haven’t competed at all in recent years. That’s why I’m a little behind. The format presented at the Olympics – a combination of the three disciplines bouldering, lead and speed climbing – doesn’t suit me, because until recently I’ve never been speed climbing. And even in bouldering I still have deficits, because I lack competition practice. So I have to think about it: Do I want to use the next two years to reduce these deficits and qualify for the Olympic Games? Or is that too time-consuming for me and I lose too much time on the rock?

There have been heated discussions in the climbing scene about the decision to combine the three climbing disciplines into one competition for the Olympic Games. What do you think of that?

I take a very critical view of the format. In the end, the 20 best combiners will go to the Olympic Games. It is not said that the best speed climbers, the best boulderers and the best lead climbers will be there. From the speedclimbing aces – except for the world champion, who automatically qualifies – nobody has a realistic chance to compete in Tokyo, because the time is too short to make up for the deficits in the other two disciplines. The best in bouldering and lead climbing may be there, but they won’t cut a very good figure in speed climbing. I don’t know what sort of impression this will make on the spectators. It’s not really the way we want to present our sport.

In what ways can competitive climbing benefit from the Olympic Games?

More funding will then be available to make sport climbing more popular and to enable more climbers to make it their profession. That would, of course, be desirable. Nowadays it is rare for someone to say that he or she is a professional climber and can really make a living from it.

You started climbing when you were a toddler. Has it become an addiction? Could you even be without it?

No. I couldn’t live without climbing at the moment. It has really developed into a kind of addiction. I started when I was five or six years old. It was great fun for me. Then it became more and more. I just couldn’t get enough of it. And it’s still like that. (laughs)

If you hang in these rocks and climb these moves that seem impossible to us, what is going on inside you?

I think for me it is ultimately a way to test my limits. Everyone has his own thing in which he is good and wants to see how good he can become. For me that’s just climbing. It is my way to let out energy and to live my dream.

Are you actually a fair weather climber?

No, I like it when it’s cold and uncomfortable. (laughs)

Chris Sharma once told me that he prefers to climb in the sun. That’s why the very high mountains are out of the question for him.

The very high mountains are also out of the question for me. There are minus 20 degrees and snow, it makes no sense to climb. But for me, it doesn’t have to be fine weather. I also go climbing when it rains or when it is cloudy.

The Huber brothers, Thomas and Alexander Huber, also came from sport climbing, but at some point they switched to the high mountains. Would that also be a perspective for the future for you?

Just now I can’t imagine going on an expedition and climbing any seven or eight-thousander in ten or fifteen years. But that doesn’t mean that it won’t happen sometime after all. At the moment, I think, I will leave it at sports climbing. (laughs)