The driving force of life: evolution

Hearing the word “evolution” might immediately transport you all the way back to you upper school biology class – to Darwin and his finches, and to Lamarck with his long-neck giraffes. Remember? In case you also recall just how boring it was, rest assured the topic is actually quite colorful:

Without evolution life would not have exploded into such colorful diversity. And without diversity of life, evolution could not work – the two are inextricably linked. (And with Global Ideas focusing on biodiversity for the next few years, it’s certainly worth taking a closer look at evolution)

Exactly what any form of life will look like (shape, colour, size for example) is mainly determined by its genetic information. And it’s at the genetic level where you’ll encounter nature’s first frontier of diversity. (Human hair for example has not the same colour for every person, but we can all have different hair colours).

At some stage our original genetic information might get altered by mutations. What sounds like a spooky scifi blockbuster kind of thing is in fact rather harmless: Think of it as a typo. If a letter in a word misspelled, you can still understand what the meaning of this word is. Over time, many mutations can occur in a species genome – most of these without any effect, a few resulting in severe illnesses, while others might turn out to be an advantage at some point in the future.

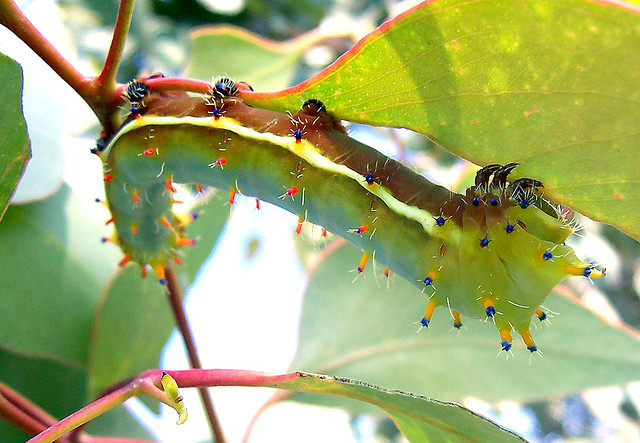

What sort of advantage might that be? Imagine, you are a rather awkward looking creature standing out from the crowd. But your unflattering appearance might actually save your life, if it helps you to disguise and hide away from predators. A British butterfly species is a good example: In its native British Isles the little fellows would live and flutter about mostly near birch trees. The butterflies used to be whitish or at least really bright in color. A few ones would don a special outfit – with black spots on their wings. (And if there was bullying among butterflies, they would have been the ones getting bullied all the time).

But in the course of the industrial revolution taking off in the early 19th century, the region turned dark and dirty from all the soot of the coal fires powering the factories. That’s when the “peppered moth” emerged: Once “bullied” for their different look, these guys now had an advantage: the trunks of the birch trees also covered in soot were no longer white. Suddenly the white butterflies were easy prey for birds, while the peppered moth now blended in very well with the dirty surface of the trees. As a result most of the white butterflies got eaten and could not reproduce anymore, the black-and-white version still could.

That’s what evolutionary biologists call “natural selection“: for whatever reason a species might come under pressure (e.g. through changing climate, food scarcity etc.), and only those species that possess adequate features will survive. This may not only be a certain visual appearance, but also a special “talent” or other characteristic, like being more resilient to drought than others. It’s possible that such features would never surface, without evolutionary pressure.

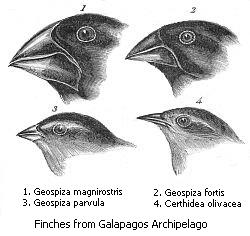

To see how this can help diversify life, we have to travel from England half way round the world to the famous Galapagos Island. There you’ll find a bunch of finches, the “Darwin finches”. They all look quite similar – apart from their very different beaks, as Charles Darwin noted back in the 1830s.

The birds all lived on the same island and used to feed on almost the same things. With all of them literally competing for the same resources the pressure was on. But birds with larger beaks had an advantage gobbling up larger grains, that small-beak-finches would not be able to pick . In turn, finches with a small beak outperformed the other ones when it came to smaller grains. In this way, over many generations one finch-species would diversify into many different finch species thereby adapting to local living conditions.

Work in progress?

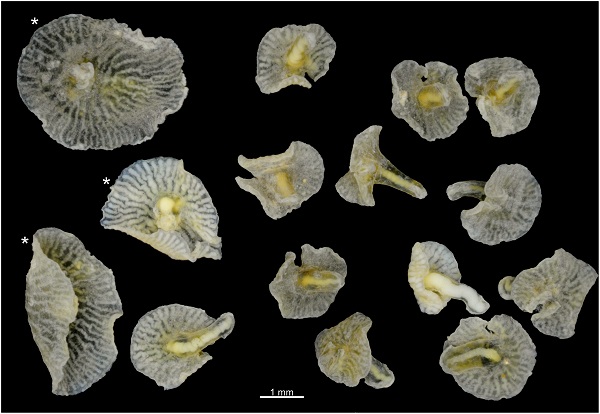

Of course, this does not happen from one moment to another. Not even over the course of individual life spans, but rather over many generations. While we cannot observe human evolution “at work”, human life spans are much greater than those of other, and particularly small organisms. To explore evolution in action, scientists therefore often choose organisms with very short lifespans, that reproduce quickly, like mealworm beetles or the three-spined-spickleback. And even if we can’t see it – humans still evolve: Some scientists say, humans are not complete yet [link German only].