Search Results for Tag: nature

Creating a water filter from wood

1.1 billion people in the world don’t have access to safe drinking water. In fact, even though it’s 2014, we still have 1.6 million people dying from infections caused by the lack of safe drinking water and basic sanitation – 9 out of 10 of these are children under the age of 5.

For several years Rohit Karnik, a mechanical engineer at MIT, had been working on the development of membranes for water filtration. But during a conference in Israel, listening to someone talking about fluid motion in trees, inspiration struck.

*

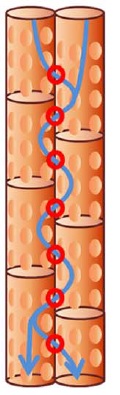

Apart from water, of course, trees transport so called “sap”, a fluid enriched with nutrients, up and down their trunks. On it’s way through the xylem, the wooden part of the tree, either fluid gets filtered at many points (circled in red). Now, why not investigate if these tree-membranes are capable of filtering water for humans as well? No sooner thought than done.

Karnik and his team started out developing a very minimalistic, low-cost filter – the problem with existing filters is often that they either need energy or are not affordable for those in need. So, Karnik’s first filters were built by peeling off the bark and plugging the piece of wood into a tube. Not suitable on a large scale, but elaborate enough for testing filter properties.

Construction of water filter system using wood*

The team’ s results: These filters got 99,9 percent of pathogens out of the water. The xylem filters managed to eliminate Escherichia coli, the most common type of gut bacteria that can cause severe diarrheal diseases if present in contaminated water.

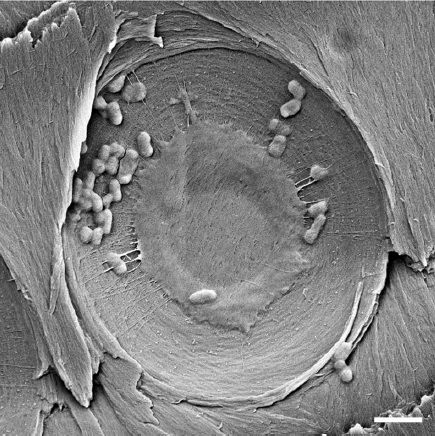

Using advanced microscope technology, the scientists even traced down, where bacteria where filtered: they all accumulated on the so called pits – membranes permeable for water – but not for the “larger” bacteria. Talking about size: the E. coli bacteria can be anything from 2 to 6µm in length. This is already quite small, but not the end of it when it comes to pathogens: viruses are almost a thousand times smaller than this. That is also where the xylem filters surrender: they don’t present an obstacle to anything smaller than 20 nm – a size comparable to that of the smallest viruses, the scientists report.

Pit membrane with accumulated E. coli bacteria. Scale bar: 2µm.*

To achieve a decent flow rate of 4 litres per day, researchers applied a pressure of 5 psi: “This value approximately corresponds to the pressure at the bottom of a 3 m column of water. Filtration will also occur at lower pressures, but at proportionally lower flow rates,” Karnik says. “The pressure of water supplied to households is typically 10 times this value. A container placed a few feet above the ground with a hose coming down to ground level will be able to generate sufficient pressure for filtration.”

Questions to be solved

Having this problem solved, there are still several left. “Can we store or dry sapwood xylem filters?” is one of the questions Karnik and his team are currently investigating. So far, to perform properly, filters have to stay wet all the time – once they’ve dried, they are useless. To safely get rid of such unusable or already “overused” filters, one way would be to burn them.

Also crucial for success of this filtration method is the type of wood used. For their experiments the team used the Eastern White Pine Pinus strobus, a tree that is abundant mostly across North America but not in those regions most in need of feasible water filtration: “We used the tree because it is common here, and it was easy to access. There are so many species of plants, and the question as to which endemic plants are suitable for making xylem filters in a particular area is certainly worthy of investigation,” Karnik writes.

Low cost solution in two years

Karnik’s idea is not yet feasible on large scales but he is optimistic: “This is a very new technology with lot of work to be done. A filter could take various forms, but one that is especially appealing is a compact device that simply attaches to a faucet, with a replaceable xylem filter inside it. It may take 2-3 years to develop the first prototypes for larger scale use, but I believe that there will be many developments to follow.”

*Credits for all images: CC BY: Boutilier et al. 2014, PLoS One 2014, doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0089934.g001

The driving force of life: evolution

Hearing the word “evolution” might immediately transport you all the way back to you upper school biology class – to Darwin and his finches, and to Lamarck with his long-neck giraffes. Remember? In case you also recall just how boring it was, rest assured the topic is actually quite colorful:

Without evolution life would not have exploded into such colorful diversity. And without diversity of life, evolution could not work – the two are inextricably linked. (And with Global Ideas focusing on biodiversity for the next few years, it’s certainly worth taking a closer look at evolution)

Exactly what any form of life will look like (shape, colour, size for example) is mainly determined by its genetic information. And it’s at the genetic level where you’ll encounter nature’s first frontier of diversity. (Human hair for example has not the same colour for every person, but we can all have different hair colours).

At some stage our original genetic information might get altered by mutations. What sounds like a spooky scifi blockbuster kind of thing is in fact rather harmless: Think of it as a typo. If a letter in a word misspelled, you can still understand what the meaning of this word is. Over time, many mutations can occur in a species genome – most of these without any effect, a few resulting in severe illnesses, while others might turn out to be an advantage at some point in the future.

What sort of advantage might that be? Imagine, you are a rather awkward looking creature standing out from the crowd. But your unflattering appearance might actually save your life, if it helps you to disguise and hide away from predators. A British butterfly species is a good example: In its native British Isles the little fellows would live and flutter about mostly near birch trees. The butterflies used to be whitish or at least really bright in color. A few ones would don a special outfit – with black spots on their wings. (And if there was bullying among butterflies, they would have been the ones getting bullied all the time).

But in the course of the industrial revolution taking off in the early 19th century, the region turned dark and dirty from all the soot of the coal fires powering the factories. That’s when the “peppered moth” emerged: Once “bullied” for their different look, these guys now had an advantage: the trunks of the birch trees also covered in soot were no longer white. Suddenly the white butterflies were easy prey for birds, while the peppered moth now blended in very well with the dirty surface of the trees. As a result most of the white butterflies got eaten and could not reproduce anymore, the black-and-white version still could.

That’s what evolutionary biologists call “natural selection“: for whatever reason a species might come under pressure (e.g. through changing climate, food scarcity etc.), and only those species that possess adequate features will survive. This may not only be a certain visual appearance, but also a special “talent” or other characteristic, like being more resilient to drought than others. It’s possible that such features would never surface, without evolutionary pressure.

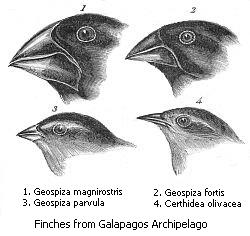

To see how this can help diversify life, we have to travel from England half way round the world to the famous Galapagos Island. There you’ll find a bunch of finches, the “Darwin finches”. They all look quite similar – apart from their very different beaks, as Charles Darwin noted back in the 1830s.

The birds all lived on the same island and used to feed on almost the same things. With all of them literally competing for the same resources the pressure was on. But birds with larger beaks had an advantage gobbling up larger grains, that small-beak-finches would not be able to pick . In turn, finches with a small beak outperformed the other ones when it came to smaller grains. In this way, over many generations one finch-species would diversify into many different finch species thereby adapting to local living conditions.

Work in progress?

Of course, this does not happen from one moment to another. Not even over the course of individual life spans, but rather over many generations. While we cannot observe human evolution “at work”, human life spans are much greater than those of other, and particularly small organisms. To explore evolution in action, scientists therefore often choose organisms with very short lifespans, that reproduce quickly, like mealworm beetles or the three-spined-spickleback. And even if we can’t see it – humans still evolve: Some scientists say, humans are not complete yet [link German only].

Departing from the world as we know it

Rich benthic fauna and associated reef fish, Southeast Sulawesi, Indonesia.

(Photo credit: Keoki Stender, Marinelifephotography.com)

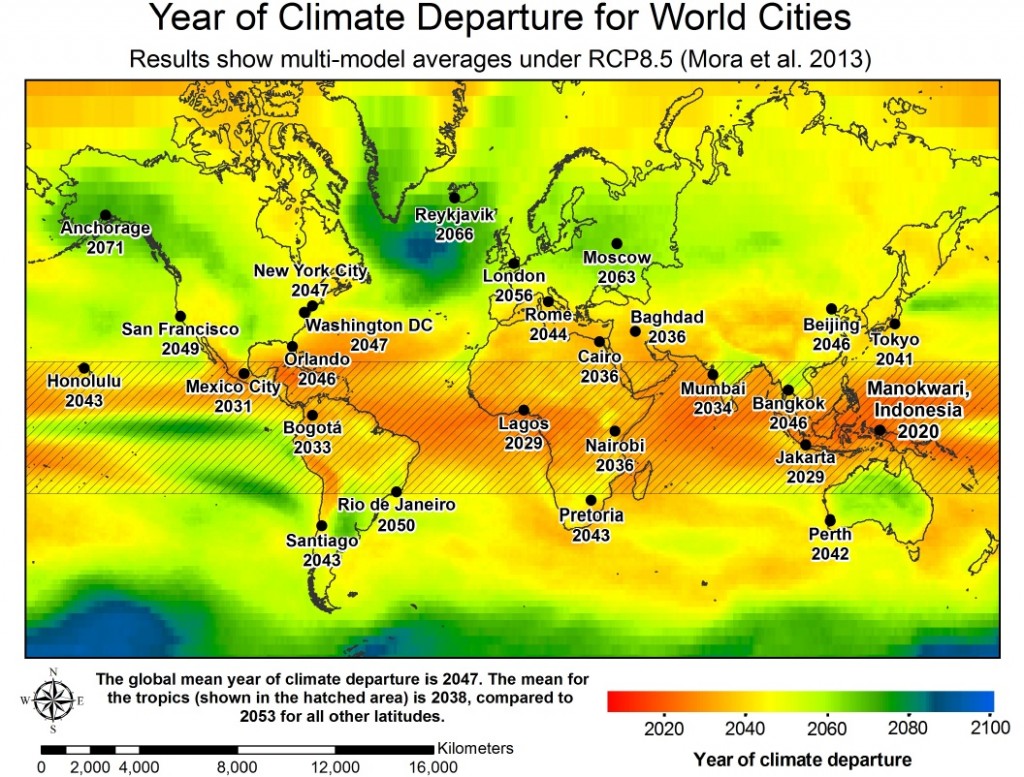

In light of the coming climate conference COP19 in Warsaw a new study published today in the scientific journal Nature highlights the importance of urgent greenhouse gas (ghg) mitigation: Researchers say that weather extremes will eventually move beyond anything that could be explained by natural climate variability.

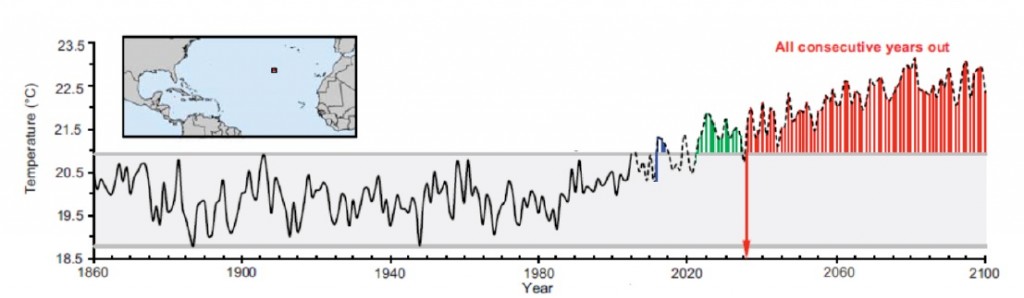

Sceptics often argue that what the majority of scientists call climate change is just natural variability. And the fact that the earth did not get warmer for the last 16 years they take as a proof that climate researchers’ predictions are wrong. Obviously climate scientists couldn’t disagree more, and this study further undermines the sceptics’ argument. From the data they conclude that at some point – the so called “climate departure” – climate extremes will even surpass anything we have have seen in the last 150 years of a changing climate.

If you think that is now at a distant point of time – far from it! Depending on the volume of GHG emitted, this “climate departure” could already happen in the middle of this century. In a low emission scenario (which requires limiting CO2 concentration to 538 ppm by 2100 – from around 393 ppm nowadays) mean climate would move out of historical bounds by 2069 on world average. In a business-as-usual scenario (936 ppm by 2100) these boundaries would already be exceeded by about 2047 on world average.

For their experiment, the researchers compared historical climate variability with the projections for a future time period until 2100. They defined historical climate variability for the period of 1860 to 2005 – a time when anthropogenic influence on climate has already been at play. Excluding this anthropogenic GHG emission from their calculations, climate departure would set in about 18.5 years early in a low and 11.5 years earlier in a business-as-usual scenario.

“The results shocked us. Regardless of the scenario, changes will be coming soon,” said lead author Camilo Mora of Social Sciences’ Department of Geography at the University of Hawaii, Manoa, in a press release. “Within my generation, whatever climate we were used to will be a thing of the past.”

Shown in grey is the historical variability of temperature. Just referring to this factor, climate depature would be at 2036 in a low emission scenario – as temperature of all following years (red area) would be outside of the historical bounds (Photo credit: Mora et al., 2013)

For their calculations of climate departure year, the team did not only look at air temperature (as shown above), but also at several more factors that determine climate change – such as sea surface temperature, precipitation, evaporation, and acidification of oceans. As these factors differ spatially, the researchers developed an map showing the departure dates for several cities.

What happens in consequence to climate departure, depends on the biological properties of that region: How well can species adapt to new conditions? Can they migrate to more suitable habitat? How will migration affect interaction with other species? In the highly biodiverse tropics (dashed area on the map) for example, the shift will occur far earlier than in other parts of the world. At the same time, precedent climate variability is quite low in this area and thus species are not used to varying conditions and might fail to adapt to new ones. That is why this climate shift threatens biodiversity of these regions.

But this is not only about plants and animals – also five billion people will be affected by the climate shift by 2050 in a business-as-usual-scenario. People, that are mainly living in developing and low-income-countries. This leads the scientific researchers to an almost political demand: “This suggests that any progress to decrease the rate of ongoing climate change will (…) require more extensive funding of social and conservation programmes in developing countries to minimize the impacts of climate change (…) if widespread changes in global biodiversity and human societies are to be prevented.”

On location in Rwanda: towering trees and crazy discussions

Modern skyscrapers and people talking to towering trees, irrepressible children who insisted on being in every frame and a heated discussion during a drive – reporter Julia Henrichmann came away with some lasting impressions while filming in Rwanda.

It doesn’t matter where you are in the Rwandan capital Kigali, chances are you’ll always find a moto-taxi (a motorcycle taxi), at your side waiting to drive you through the lush green valleys dotting the city. On the one hand, Kigali is a modern city with skyscrapers, busy streets and crowded shops. On the other, it’s also not unusual to come across pockets where some of the most amazingly large trees and plants find space to grow.

To get a sense of how big the trees are, I asked our driver Ismael to stand next to one I liked very much. He suddenly touched the tree and began talking to it. I asked him why. “Oh,” he said. “This must be a very old one, much older than me so I have to treat it with respect.”

I cannot say whether people are as respectful of nature everywhere in the country. There are many areas in Rwanda where people cut almost every tree for firewood. Gathering firewood is normally done by children. Some don’t go to school because of the long distances they have to walk to get firewood. It’s a problem that’s worsening by some estimates. Firewood is used in homes for cooking because there’s often no electricity. Many use diesel generators.

When we came to the countryside to the district of Nasho, many children wanted to touch me. Most of them had never seen a white person because they had never traveled beyond their district. They were delightful and innocent in a way that I have never seen children elsewhere. Maybe that’s because they did not expect anything from me. All they wanted was that I listen to them and spend some time with them (even though I did not understand their language).

And, of course they wanted me to take photos with them, even during the filming. They walked into every frame! How could we tell them that we just wanted Anastase Tabaro in the film, the man who brought electricity to their village? So we decided to make them part of the film. The villagers’ happiness and pride was palpable as they led us to the little hydro-electrical pump Anastase Tabaro had built for them.

Driving back to Kigali, we had a crazy animated discussion in the car and I became a bit alarmed that the Rwandans would come to blows. So they stopped talking in their native language and switched to English and French for my benefit. And so, what was the big discussion about? What’s the topic that pops up in conversations in Rwanda sooner or later? The genocide.

Even though it happened almost 20 years ago, everybody still talks very much talks about it. Every family here has been affected personally by the tragic event. When you come to Rwanda, you should no longer ask: “Are you a Hutu or a Tutsi?” That’s not the question anymore. The question we argued about in the car was the role of the media during the war and the genocide. Do you as a camera crew film or do you help the victims lying at your feet? During the three-hour drive, we came no closer to any answers. You will probably never find them.

Act now – or you’re (perhaps) wasting money

If planet Earth’s fate is not strong enough an argument for fighting climate change, perhaps money is? Researchers now calculated the costs of climate change: They found that costs enormously increase the longer politicians put off taking action. So are our economies prepared to take the hit?

About 200 country leaders agreed at the UN climate conference in Doha last December to (further) lower greenhouse gas emissions from 2020 on. That is how they want to keep global warming in check limiting it to two degrees compared to the preindustrial level. “If you delay action by 10, 20 years you significantly reduce the chances of meeting the 2 degree target”, Keywan Riahi, IIASA energy program leader and study co-author told Reuters news agency.

The scientists developed a freely available software-tool to test under which conditions the two-degree-target is most likely to be obtained. For the first time, they included all important variables in their calculation: the time elapsed until first action takes place, future energy demand, carbon prices, new energy technologies, and uncertainty about how the climate system reacts.

Though all of them are important, the most crucial one is the time it takes until you take action, Riahi says: “With a twenty-year delay, you can throw as much money as you have at the problem, and the best outcome you can get is a fifty-fifty chance of keeping temperature rise below two degrees.”

Feedback