Muslim, non-Muslim

“Look Dad, I made a temple with LEGO, just like the one I visited with Ma!”

“Look Dad, I made a temple with LEGO, just like the one I visited with Ma!”

“Don’t make a temple dear. Construct a mosque.”

“But why? Why not a temple?”

This was a conversation between a six-year old and her Pakistani father residing abroad. This was a conversation reflecting the fear of losing one’s sense of self; the self that one finds in a place which is statedly non-Muslim; the sense of self that is only linked to your own religion and nothing beyond.

I always felt that the amount of exposure you have impacts the way you look at life and at people belonging to other religions or cultures. Logically, when people migrate from thirdworld countries, where religion is the staple to more modern societies, their horizons should broaden. Their intolerance and strong judgment should reduce as then they would meet people who are as real as themselves.

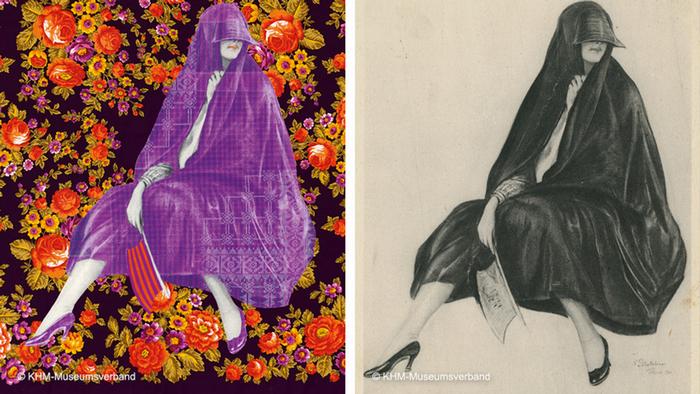

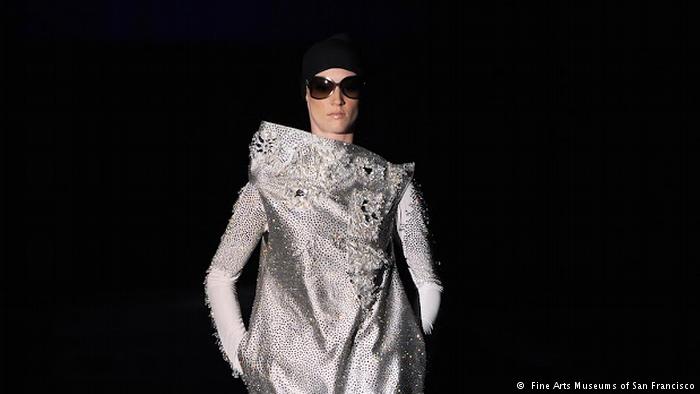

On the contrary, a common trend I have witnessed and personally experienced is that many people tend to become stauncher in their beliefs. They retreat into the comfort of their old values and ways, at least within their families, and become even more skeptical about “the others.” More men start sporting beards and more women begin to wear hijabs and burqas (head and full body veils). They choose to limit their social interactions to their “own kind.” People who have never offered Namaz (prayers) in their lives as non-pious Muslims in their own countries are seen bowing their heads- if not five times a day, then at least on Fridays.

Religious festivities become more pronounced than usual. Whereas there is nothing wrong with that as long as all this is a personal choice and doesn’t become a case of comparative analysis and strong biases. An issue especially arises if this phenomena takes over one person in the family and the rest go on living as usual, finding excitement and pleasure in interacting with people from different nationalities and cultures. The clash of “values” leads to frustration and discontent and in my case, divorce.

I remember when we moved to Bangkok, it was my first exposure to the international world. I was more concerned about people judging me for being a Pakistani and I forgot to spend my energy on judging them. I was lucky to come across beautiful, non-judgmental people, some of who are now my best of friends despite my return to Pakistan. I was even luckier to find an art residency that promoted my photographic work, work that was never given any importance (and still is not) in my own country.

I got to experience the colors of various cultures, got to take long walks alone at night without the fear of being mugged and got to wear whatever I wanted without being stared at. Unfortunately, in our Pakistani community, I turned out to be a rare commodity. Most Pakistani people would choose to interact with “firangs” (white people) only on need basis. Socially they kept themselves to small groups of Pakistani families. The criteria for the success of such social interactions was based on inviting the group over turn by turn for “dinners” or “lunches,” which of course had to be home made, the menu Pakistani and the clothes even more so.

I understand the psychological impacts of moving out of your comfort zone and being a minority. One tends to be more at ease among people of your own religion and culture. But I do not understand how they suddenly become more religious, more traditional and less tolerant. I can never forget an interaction with a Pakistani family when they casually asked me what I was up to these days. I was glad someone asked me this question and explained how I was volunteering for a magazine as a sub-editor. I eagerly explained that my boss was an Israeli woman and I was glad that my nationality had never been a cause of any discomfort in our work and friendship.

“How could you socially interact with a Jew? You know it is even allowed to kill them,” was her response. I refused to interact with that family again, much to the dislike of people who were my own. Eventually my “firang” friends were labeled as the reason for my discontent in my interactions as “those people” had no values and of course I, no spine.

In my three years abroad I have come to realize that human hatred has got nothing to do with geographical boundaries. It is an emotion we carry within ourselves no matter where we go. Our sense of self-righteousness leaves us incapable of giving anyone an honest chance to be someone more than his or her religion or culture. Our judgment of us being right gets converted into our judgment of them being wrong. I wish a day comes when human interaction becomes pure and devoid of judgments on anything other than humanity.

She goes, “Look Ma, I made a mosque with LEGO,” and I thought, aren’t there already too many…

Author: Soofia Says

Editor: Manasi Gopalakrishnan