No shame, just name

An undated handout picture released by the Frida Kahlo exhibition press office on 18 March 2014 shows a photograph ‘Frida with a blue dress’ 1939 by Hungarian-born US photographer Nickolas Muray.

I never used to be a big fan of Salma Hayek – not until she played in “Frida” the biopic of the Mexican surrealist painter and feminist icon Frida Kahlo, released in 2002.

That was also the year that I happened to turn 30. Having spent my twenties trying to figure myself out, 2002 marked the advent of accepting myself – warts and all. And Frida (masterfully reincarnated onscreen by Hayek) was just the model to cement my then developing devil-may-care attitude towards other people’s opinions about my looks, my clothes, my outspokenness or my refusal to unquestioningly accept societal indoctrination about marriage and the role of women.

To some, I was a non-conformist and watching “Frida” hit home the fact that there is beauty in non-conformity too.

Here after all was an openly bisexual woman (we are talking about the first half of the 20th century!), who sported a unibrow and a hint of a moustache, was able to rise above disability and pain (both physical and emotional) and transferred all of it in technicolor glory onto canvas.

Even Kahlo’s naïve paintings resonated with me. You see, art wasn’t a topic in which I was particularly well-versed. This is partly because the environment I grew up in treated any form of art as a fanciful pastime for the better off, not something that would fill your rice bowl.

Salma Hayek as Frida Kahlo

Art lessons in school didn’t include or introduce us to renowned artists, and some of my teachers instilled in us the flawed (in my view) concept of “good” and “bad” art. Kahlo’s art probably wouldn’t have passed muster for one particularly strict art teacher, whose idea of “punishing bad art” was to tear your art block to pieces and scatter these like confetti before your unbelieving eyes.

In short: “Frida” struck a chord on several fronts, and Hayek’s performance doubtlessly helped to give me an insight into a personality “hailed as an icon of female independence and artistry and inspired generations of artists, bisexual women, students and LGBT activists.”

So, imagine my shock when I chanced upon Hayek’s New York Times op-ed on 12. December describing how she too fell victim to the unwanted attention of that weasel, Harvey Weinstein. No, strike that: I shall not insult mustelids by associating them with the diabolical Weinstein.

He seems to be a brute unto his own, if the litany of abuse, manipulation, and threats that Hayek and many others endured is to be believed. It’s all the more ironic that Hayek was portraying an almost indomitable female personality onscreen, whilst fending off a predator drunk on his male privilege off-screen.

I know. Naysayers (and his lawyers) might argue that Weinstein is “innocent until proven guilty.” Yet far too many women – all with much to lose – have come forward, and their stories aren’t that different from Hayek’s. So excuse my prejudgment.

Harvey Weinstein

Hayek’s account has gnawed at me because it also illustrates how many hoops she was willing to jump through for this brute just so that all her hard work would see the light of day. All she wanted was for the biopic of Frida to be out there. All she lacked was the clout that Weinstein had in Hollywood.

She claims to have been finally forced to relent and to do a sex scene he demanded, which actually sickened her to the core. Weinstein’s spokesperson has since claimed that he “does not recall pressuring Salma to do a gratuitous sex scene with a female co-star and he was not there for the filming.”

I think that what resonates most with me is how she justified this final, uncomfortable decision of hers: that the hard work put in by others would also come to naught if she refused, and he then axed the project.

If you ask me, it goes back to the core social conditioning of women: to be self-sacrificing. To always consider how our private decisions might have a collective or communal effect.

Sure, I can understand if this relates to launching a ballistic missile or detonating an explosive or pulling the trigger on a semi-automatic weapon. Then yes, by all means, please reconsider the consequences of your actions, whether you’re a man or a woman.

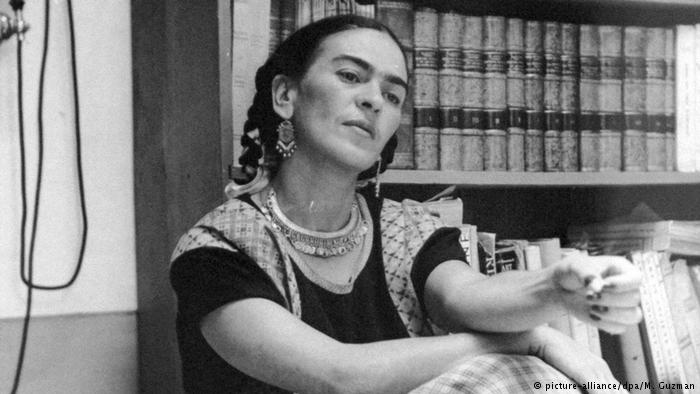

Frida Kahlo

But why is it that when a woman has been sexually propositioned, harassed or assaulted she must think twice or thrice of the consequences for others, including the perpetrators? Why shouldn’t she put herself first?

I guess this question has been asked long and often enough and one can only hope to witness a sea change thanks to the #metoo movement. Until then, I guess our mantra should be “no shame, just name.”

Salma, I salute you for your courage. Frida would have been proud.

Author: Brenda Haas

Editor: Anne Thomas