Yet again, studies show how revealing phone data is

Icon by Anubisza

Many governments agencies around the world collect communications data as a matter of course. In the past, governments have downplayed privacy concerns around this data collection by emphasizing that they don’t collect the actual content of communications but rather so-called “metadata” – that is, the number called, what time the call was made, how long the call was and where the call was made from. A number of recent studies have demonstrated, yet again, that this metadata can be incredibly revealing.

And this is where journalists need to pay attention because if they want to keep a story they’re investigating under wraps or protect contacts, they need to understand how their metadata can be used to discover their activities and movements.

Who are you calling?

Researchers at Stanford University in the US, for example, are asking volunteers to install an app called MetaPhone on their mobile phones. The app collects their metadata. The results so far, says researcher Jonathan Mayer on his blog, “took us aback”.

By searching telephone directories, it was often easy to find out who exactly people were calling. And by analyzing patterns of calls, the researchers were able to uncover highly sensitive information, such as medical conditions, pregnancies or interest in firearms.

The researchers gave several examples of what they found out purely by looking at phone data – here’s three of them.

- “Participant A communicated with multiple local neurology groups, a specialty pharmacy, a rare condition management service, and a hotline for a pharmaceutical used solely to treat relapsing multiple sclerosis.”

- “Participant C made a number of calls to a firearm store that specializes in the AR semi-automatic rifle platform. They also spoke at length with customer service for a firearm manufacturer that produces an AR line.”

- “Participant E had a long, early morning call with her sister. Two days later, she placed a series of calls to the local Planned Parenthood location. She placed brief additional calls two weeks later, and made a final call a month after.”

Simple to map movements and daily routines

Plotting the movements and communications of an individual from their cell phone data has been done before. But a new visualization showing the mobile phone and email data of Swiss politician Balthasar Glättli highlights once again how much the data reveals when it is collected in bulk. (The Greens party politician released his communications data in protest at a proposed extension of Swiss data retention laws – you can read more about this here.)

The analysis of six months of Glättli’s metadata shows the pattern of his daily activities such as when he normally goes to sleep, when he starts and finishes work, who he regularly meets with and when and how often he talks to certain people.

Created by OpenDataCity (an English version is not available)

When people send an email or SMS to several people at once, this information is also included in the metadata. As such, access to Glättli’s communication data enabled the analysts to create a picture of not just who Glättli was in contact with, but also who his contacts were in contact with.

Norbert Bollow from the Digital Society Switzerland, one of the Glättli visualization project members, says that metadata is even more dangerous when information from multiple people is put together.

“Then it really starts getting dangerous,” he said in a Skype call with onMedia. “You can start making connections between people and with little effort, start profiling people and knowing about their medical conditions, their religious views and their political beliefs.”

What does this mean for journalists, activists or whistleblowers?

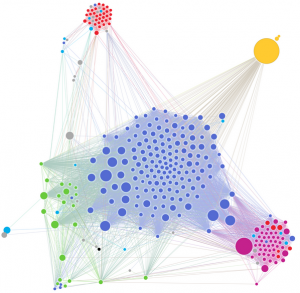

Glättli’s contact network by OpenDataCity

Bollow warns that agencies can easily reconstruct a journalist’s research or retrace a source’s movements from metadata.

“You can make a real time profile of what kind of story they are working on and more dangerously, who they are talking to,” he said.

“A journalist who wants to know what is going on at an oil company will try to make contact with someone who can give him information. And the secret service will know immediately who are those insiders who have had contact with journalists.”

Where to find out more

It’s not just phones that create metadata, but virtually everything we do in the digital world – from surfing the internet to paying with a credit card in a store. To find out more about ways in which journalists can be more secure in their digital communications, take a look at the posts and sessions from DW Akademie’s digital safety workshop.

Tactical Technology Collective’s Security in a Box also has an excellent array of digital security tools and tactics in a variety of languages.

DW Akademie’s Steffen Leidel will also be talking on how digital safety can best be taught to journalists at the International Journalism Festival in Perugia on Thursday 1 May at 14.00 in the Sala Perugino (Hotel Brufani).

Written by Kate Hairsine