Think before you map: Learning from Egypt’s HarassMap

In 2008, Ushahidi first mapped post-election violence in Kenya using information sent in by people via sms or online. Since then, thousands of organizations have used Ushahidi or other mapping tools to crowdsource information and present it on a map. The uses have been myriad, from mapping the crisis in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake to getting feeback about dangerous bike paths in Berlin.

In 2008, Ushahidi first mapped post-election violence in Kenya using information sent in by people via sms or online. Since then, thousands of organizations have used Ushahidi or other mapping tools to crowdsource information and present it on a map. The uses have been myriad, from mapping the crisis in Haiti after the 2010 earthquake to getting feeback about dangerous bike paths in Berlin.

After all, crowdsourced maps are often an easy way to put visuals on a web page and show what’s happening in places that reporters or rights activists can’t or don’t get to. But this doesn’t mean media organizations or advocacy groups can slap together an online map and people will automatically start sending reports. Many crowdsourced reporting projects are unfortunately short lived, attracting few reports and having little impact.

HarassMap has won several awards for mapping incidents of sexual harassment in Egypt. onMedia takes a look at what the organization has learned since it launched in 2010.

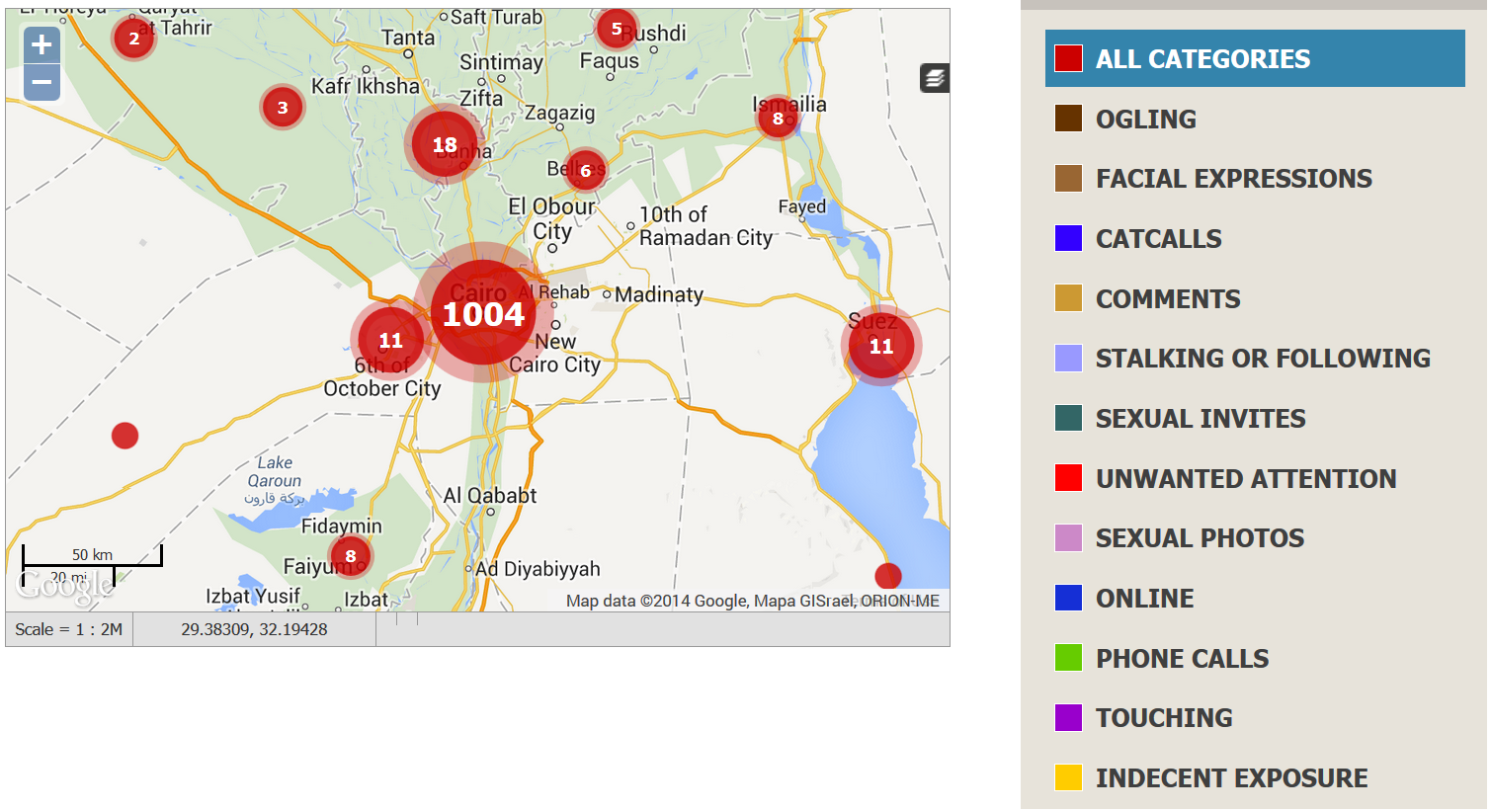

HarassMap‘s goal is to make sexual harassment no longer acceptable in Egypt. The independent initiative combines community outreach programs with a digital platform that lets people report sexual harassment either directly on the HarassMap site or via Facebook, Twitter, email or text message.

The HarassMap founders decided to use an sms-based system as it gives people without access to a computer the chance to report harassment. Even back then, nearly everyone in Egypt had a mobile — the country’s mobile phone penetration rate in 2010 was 97 percent.

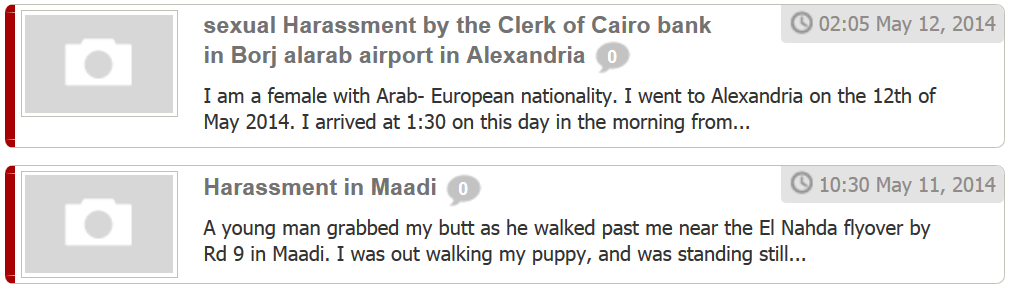

The initial idea of the platform was to create a “safe space” where people could anonymously talk about harassment, said Noora Flinkman, the head of marketing and communications at HarassMap. Sexual harassment was then (and still is) a relatively taboo topic in Egypt and there were virtually no other initiatives addressing the problem. At the same time, the map would provide a tool to show the reality and scope of the issue.

Filling a need

“When we launched our reporting system, it crashed because we had so many reports,” Flinkman told onMedia via Skype from Cairo.

After this first torrent of messages subsided, the site began to regularly receive around 40 reports a month. For the HarassMap founders, the information was a “gold mine” on a subject about which there had been very little research.

In the first year, the initiative collected nearly 700 accounts (to date, they have just over 1,300). It analyzed the data, which revealed that women in both rural and urban areas were victims of harassment, that it wasn’t restricted to particular areas in cities, social background or age, and that it took place independently of what women were wearing or their nationalities.

In the first year, the initiative collected nearly 700 accounts (to date, they have just over 1,300). It analyzed the data, which revealed that women in both rural and urban areas were victims of harassment, that it wasn’t restricted to particular areas in cities, social background or age, and that it took place independently of what women were wearing or their nationalities.

The knowledge was then used by outreach volunteers when they went out to talk to people in the streets. It also informed the initiative’s anti-harassment campaigns.

“These reports were definitely really, really important,” said Flinkman. “We wouldn’t necessarily have had this type of information as quickly and in the same way if we hadn’t had the reporting system.”

At the same time, the site received 76,000 unique visitors in its first year, showing there was a real interest in finding out more information on the subject. The media, both in Egypt and internationally, reported on the site, increasing its profile.

Ups and downs

However, the number of reports received by HarassMap has slumped over the past year to around just five a month.

According to Flinkman, there are two main reasons for this. When HarassMap started, no one else was really using such a platform to document sexual harassment and social media sites such as Facebook and Twitter weren’t as popular. Now, many groups are addressing the issue and people often use these groups’ Facebook accounts to share stories.

Earlier in 2014, the organization ran a campaign to encourage more reporting, which did result in a boost.

But as a result of these ups and downs, HarassMap is now evaluating how they should develop the platform.

The next step

One possibility may be for HarassMap to act as a so-called aggregator, to use the site as a place to collect stories on sexual harassment coming from multiple media platforms and organizations. This would allow the mapping of information without people having to know about HarassMap specifically or having to send a report directly to them.

Another possibility is to create an app to simplify the reporting itself.

“We don’t have the best way of reporting; we don’t have the best system or the most beautiful map and the most user-friendly reporting,” Flinkman said. “Creating new ways of reporting that are more sexy can also give people an incentive to send us information.”

Such as app could also ask for different kinds of reports. Currently, HarassMap only collects incidents of sexual harassment from victims. One option to extend this might be to ask for reports where bystanders or witnesses have intervened. That would add another layer of information.

What they’ve learned

Flinkman stresses that it’s vital for organizations to have a strong sense of their goals before they start.

“We spent years analyzing the issue in Egypt – the different dynamics, what had already been done, what had not been done, what seemed to work, what doesn’t work,” she said. “This is why it took us years to actually launch: we did a lot of planning.”

And then while organizations are up and running, a “key part of the work” needs to constantly appraising strategies, programs and activities, especially since the digital world changes so rapidly.

“You need to have this constant process of evaluating and analyzing yourself,” she added. “That’s the most important thing.”

ALSO SEE

Innovative journalism and advocacy projects

Tweets help visualize information density of African cities

Crowd reporting puts the squeeze on traditional journalism

Author: Kate Hairsine, edited by Kyle James