Keep to +2 degrees might not prevent permafrost from melting

- Large Ice Hall in Ledyanaya Lenskaya Cave located inside continuous permafrost (Photo: (C): Sebastian FM Breitenbach)

- Frost crystals at the entrance of Ledyanaya Lenskaya Cave (Photo (C): Vladimir V Alexioglo)

- Close up of frost crystals (Photo (C): Vladimir V Alexioglo)

Large parts of the Northern hemisphere from Alaska to China hold a dangerous treasure. 24 percent of this land’s ground is frozen throughout the year – so called permafrost. It holds more than 1,000 gigatons of the most dangerous greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide and methane. Release of those would accelerate climate change to great extend.

Now, researchers found evidence that permafrost could start melting already at a 1.5 degrees Celsius rise in temperature. Also, the world already warmed up by 0.6 to 0.7 degree Celsius compared to the preindustrial level. So adding another 0.8 could already let permafrost melt.

That’s at least what happened in former times, as the scientists from Britain, Russia, Mongolia and Switzerland found out. They went into Siberian caves located along the ‘permafrost frontier’ studying stalactites and stalagmites as they function as a kind of climate archive – they only grow when liquid rainwater and snow melt drips from the surface into the caves.

“The stalactites and stalagmites from these caves are a way of looking back in time to see how warm periods similar to our modern climate affect how far permafrost extends across Siberia”, said Dr Anton Vaks of Oxford University’s Department of Earth Sciences, who led the work.

The amplifying effect on global warming the release of greenhouse gases held in the permafrost would have, exceeds everything climate models yet suggest. So, though almost 200 nations agreed in 2009 to the 2 degree target for global warming, this may not be enough to keep permafrost from melting and thus to mitigate climate change.

Fracking: Promised Land

Following the international premiere of “Promised Land” at the packed Berlinale film festival press conference in Berlin last week, actor Matt Damon said the movie, directed by Gus van Sant which deals with fracking, is a film about American identity but at the same time a global issue.

The film’s international premiere was accompanied by news agencies announcing that Russian gas company and exporter Gazprom plans to cut gas prices for European customers in the billions in 2013. According to several experts, this maneuver could be linked, besides strong competition in the liquefied gas export sector, directly to sinking gas prices: the fracking boom in the US is believed to have already lowered international gas prices even though the US is not exporting gas (yet!) to Europe.

It’s yet another example of the so-called US shale gas revolution that’s already transforming the political global power structure. And it looks like fracking will likely increase globally for geostrategic, power and profit reasons in the next years.

“Promised Land” takes place exactly against this backdrop. It takes an in-depth look at how the industry operates and shows the possible consequences by using an intelligent and precise analogy of a psychological war happening in the US in areas with huge underground gas reservoirs. It focuses on how a nine-billion-dollar corporation tries to get its hand on much-needed land, how they operate psychologically and what alternatives citizens are left with. The film shows how the corporate salesman Steve Buttler (Matt Damon) and his colleague Sue Thomason (Francis McDormand) work hard to buy the village community with some entertaining and clever twists and turns of the plot.

The main aim of the film obviously is to raise awareness among people and to get them to think deeply about the dynamics and consequences of fracking. Matt Damon said after the premiere that if you are searching for more in-depth information about the fracking process you should research online. It would be simply impossible to lay out all the pros and cons of fracking in one feature film but it’s still packed with information.

The movie avoids black and white clichés, but it’s pretty clear that the makers of the film care about the “small people” and how big corporations are trying to manipulate them with scare tactics and playing on existential fears – circumstances which have heightened in the last decades through an unsustainable neoliberal capitalistic system. It is pretty clear that the corporation in the movie is a child of that system and that the same unregulated system produced and created in many ways the situation the village’s residents are in right now: earning less money, living in constant fear of losing their jobs, drowning in debt, not being able to give their children a decent education, not knowing if they can die with dignity.

The film addresses all these issues but it hasn’t been too successful in the US. It remains to be seen how it will fare at the international box office and what impact it will have on the ongoing fracking debate.

Facebook of the forests

Put up a camera. Anywhere. You will be surprised by just how badly everyone wants to be on telly whenever they see a lens pointed at them. It’s why many kids think web cams are more important in a computer than a CPU, and also a reason why Big Brother revolutionized trash TV and Facebook made Mark Zuckerberg a Billionaire.

The urge to exhibit one’s private persona seems so deeply ingrained in the human psyche, that you begin to wonder if it’s an evolutionary trait also present in other species. And indeed it is. Forest animals love the camera. The TEAM network has put up camera traps in forests across the globe to snap photos of animal wild life. The experts of TEAM (or, more accurately and less sexy “Tropical Ecology Assessment and Monitoring”) are now celebrating the 1 millionth photo taken.

TEAM makes the photos available to researchers and the public as “real-time” data to help track how biodiversity evolves. And, of course, also to show how wild life is impacted by changes in their environment – be it deforestation or warming temperatures. The primates shown below are an example of the quite entertaining footage collected by the scientists:

The TEAM network still has some way to go: With a million plus photos they are way behind Facebook – that other network providing real time data on a not so different type of primate: you and me.

When climate pays for financial crisis

Once upon a time, politicians had a good idea for how to create incentives that make companies want to become greener. Companies were to buy certificates for the amount of carbondioxide they emitted – one certificate for every ton. The more carbon – the more certificates they had to buy. The less CO2, the less certificates. So far, so good.

Initially sold for 20 Euros a piece, the price of certificates rose to a record 32 Euros before embarking on a steady decline: At the end of January it dropped to an all-time low of 2,81 Euro. We were wondering what the reasons for and the consequences of this low price might be, so we’ve asked Christian Linden from the German Emissions Trading Authority to give us some input for our FAQ.

How come the price for emissions certificates is nose-diving so badly at the moment?

At present supply outweighs demand. That’s for a number of reasons: companies were allocated certificates too generously at the start of both, the initial and subsequent trading periods. Plus, the economic and financial crisis has led to a decline in industrial production, which in turn brought about a decline in CO2 emissions. As a consequence companies have accumulated a surplus in certificates, which is now flooding the market, bringing down the price.

Another argument could be that some companies have already became greener, which means they need fewer certificates (German source).

What happens if the price stays that low?

There is little incentive to invest in climate friendly technology, if it’s too cheap to carry on producing goods in a way that harms our climate.

What can be done to get the certificate prices to rise again?

In the short term, a good idea is what the EU commission has suggested: to temporarily keep a certain number of certificates – they are talking about 900 million – out of the market. In the longer run it’s important that on a political level an ambitious climate goal is agreed to reduce carbon emissions in the EU by 30 percent until 2020. This would raise the pressure on companies to reduce their emissions.

What’s the “right” price for a certificate?

It’d be a price that motivates businesses to reduce emissions and/or invest in climate friendly technology. For some companies this might start at 15 Euros a ton, fro others it may be closer to 25 Euros. So, here is no single “right” price.

Scientists turn trash into crude energy

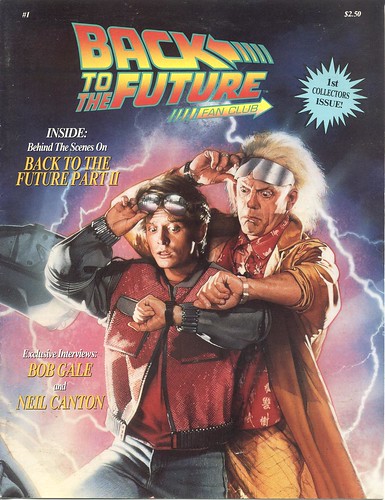

Remember Doc Brown? That crazy, white haired caricature of a scientist from the 1980s blockbuster scifi comedy Back to the Future? He’s the inventor of a spectacular (and – sadly – fictitious) device called the flux capacitor that is running first on plutonium, later on ordinary household garbage to power a time machine. Here’s what it looks like when Doc Brown is searching for fuel:

Scientists in Denmark have now hit upon a novel way to do just that: producing energy from household waste. While not quite matching Doc Browns achievement when it comes to the amount of energy harvested (let alone building a time machine) the scientists’ feat is impressive enough: Feeding biomass (comprising anything from sewage, compost, household garbage or waste from meat and dairy production) into what is essentially a 400 °C hot pressure cooker they managed to create something very close to fossil crude oil. What’s more, the production process used is more energy efficient than any other way of getting energy out of biomass.

We figure, if the Danish research team is still unhappy with the energy yield of their trash, they only have to wait another two years for expert help: In Back to the Future – Part II we learn that Doc Brown is going to visit us in 2015.

Feedback