Innovation driven by Africans

In many African countries power cuts and poor access to the internet are common. But this is just one way of looking at the continent. Another way is to explore the dynamic and confident tech start-up scene brimming with creative ideas. Erik Hersman, technology blogger and co-founder of the internationally renown crowd-sourcing platform Ushahidi, is working to better connect African innovators. In Nairobi he founded iHub – a centre supporting a thriving technology community that has inspired more hubs across Africa.

In many African countries power cuts and poor access to the internet are common. But this is just one way of looking at the continent. Another way is to explore the dynamic and confident tech start-up scene brimming with creative ideas. Erik Hersman, technology blogger and co-founder of the internationally renown crowd-sourcing platform Ushahidi, is working to better connect African innovators. In Nairobi he founded iHub – a centre supporting a thriving technology community that has inspired more hubs across Africa.

On Twitter Hersman is known as @whiteafrican – he grew up in Kenya and Sudan and these days lives in Nairobi. If you’re looking into innovation in Africa you can’t go past Hersman. He’s an expert on the technology landscape of the continent – which is completely different to Europe or the USA. At the recent German internet conference, re:publica, Hersman presented the prototype of a mobile router designed to provide an internet connection even in remote and difficult conditions. This battery powered device called BRCK can switch between ethernet, WiFi, and 3G or 4G mobile phone networks and allow up to 20 users to connect to the internet. DW Akademie’s Steffen Leidel caught up with Erik Hersman at re:publica in Berlin to talk about innovation in Africa.

Do you think the new Silicon Valley or Silicon Valleys of the future can be in Africa or Latin America?

It’s not a simple question. In short, yes I think that there are going to be clusters of technology, innovation and entrepreneurship in Africa and Latin America, and Asia and elsewhere, but it’s going to have a different flavour and different feel than just the Silicon Valley model. I think the models will differ because the cultures differ and the people differ.

But what flavour would it be?

In Africa we see a lot of mobile focus on things. And also we have a different type of investment climate. So I don’t know if the model would look more like Israel in the future. Israel is very much focused on education around technology, heavy local investment in technology and then in spinning those companies out or selling them to other markets. It’s an interesting model. I think rather than trying to grow these huge vertical companies, in maybe South America or Africa, it might make more sense to, at first anyway, grow companies to a certain level and then figure out how they fit into the world stage, and then go to the market that best suits them. My best example of this would be South Africa. What they tend to do is start up a company and then move half of the company to maybe San Francisco or the UK. They will have those guys working on the business and operational side and their development team or the product team will be still back in South Africa. So they can still take advantage of connections on one side but production costs on the other. So you have to think about the ecosystem, you actually have to think about the products too first, because each company has to answer these questions on a very visceral level in order to stay alive and they have to answer the questions about capital, reach and costs of doing business. I know that’s a very long answer – it is a complicated question and the models are still being figured out.

You talked a lot about Afrilabs and the growing network of people in Africa doing innovative things, so where does the power of innovation come from? Is it just western companies bringing their know-how to Africa or is it something else?

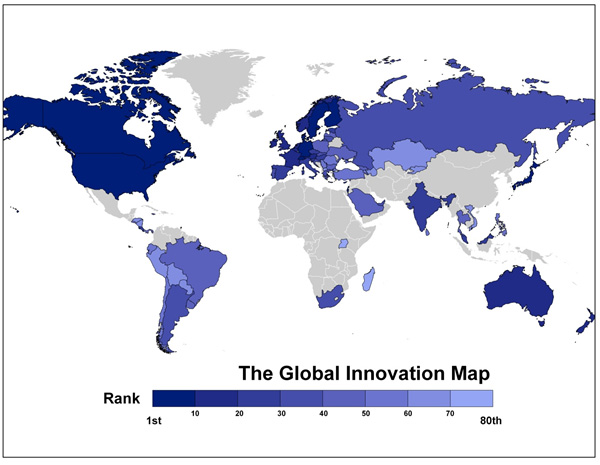

Innovation is something that is a human trait – it’s not just a product. It’s what people do. So don’t do innovation: innovate. It’s an action, a verb – it’s something that you do. Products can be innovative but it’s a people thing. Is there more innovation in products or services in Europe or America? Actually I don’t think so at all. There are different types of innovation that are happening and it is just recognised and talked about more in the West than it is in places like Africa and Latin America. I showed a map in my presentation of a kind of a global innovation landscape across the world and you will see big empty patches in certain continents. And again, it is not because there is no innovation happening there, it’s just that they do not count because there is no pattern for them.

So is it possible to accurately measure innovation?

The way of measuring innovation is skewed in the favour of western nations. The definition of an innovation index and how it’s defined right now is around patents. When you have 70% of your economy based on informal sector work, that does not mean that they are not inventing new things and innovating on other products or services, it just means that they are never going to be registered as patentable or they are never going to be patented there. The cost of patenting alone is much too high, much less the chance that you can actually protect it if you were to protect it. So why would you spend the money to do it? Instead of using just patents as a way to measure innovation, there needs to be some other measurement indicators if we want to truly measure innovation across the globe.

Are tangible indicators a problem for you in the same way the media development sector looks for indicators? Is it a problem for what you are doing, particularly for seeking funding?

I think there it goes deeper. The narrative about Africa, in Europe in US where a lot of foundation money comes from, is still of this Africa of the 80s and 90s. It is still hard for some of the groups that represent capital, even investment capital, not just foundation capital in the northern continents, to understand what is going on. So first they have to understand the narrative, and then they have to think about how they could invest in that future. We are starting to see some change and understand that a little bit better. For example, GIZ flew in the Afrilabs managers – some 15 tech hub leaders from across Africa. I think 13 different countries are represented here in Berlin [at re-publica] which is an investment by a development organisation, a foundation type organisation, into Africa because all of us have not met before in person. So this is a chance to really create some bonds between us and hopefully that will mean greater acceleration in learning about how to run tech hubs better and that would then trickle down to people who are using the tech hubs and we will see better start-ups, better freelancers, better cooperation between not just the hubs but the companies who are at these hubs.

How would you pitch the new narrative of innovation in Africa?

This generation of Africans is looking not for handouts but to create businesses and grow their own part of Africa. That does not mean that there is not room for outside players to invest. But it does mean that this has to come without so much of the agenda driven by outsiders but driven by insiders – driven by Africans themselves.

What’s your thoughts about the digital divide? In many parts of the world the internet is a force for change but not everyone has internet access, or it’s too expensive.

Well, there is water and there’s internet, there are mobile phones and there is food and there are all these things. Maslow’s hierarchy of needs still stands: you need to have shelter, food and water and security before you have some of these other things. But sometimes, mobile phones and internet can help provide those for you. There is also this digital divide term that is interesting. Is it the division between rich and the poor, or is it between urban and rural? I lean towards the second. I say the digital divide is much more between urban and rural because you can be poor in a major city in Africa and still have connectivity or you can still have a phone or have access to one. But sometimes in the rural areas you can have more money but have a lot more difficulties with connectivity. So I think urban and rural is actually more important right now than rich and poor on the digital divide side.

Do you expect a mobile internet revolution with the move from feature phones to smartphones in Africa, or will SMS continue to play an important role.

I think the simple technology is still the default – the lowest common denominator. SMS and USSD (Unstructured Supplementary Service Data) is the reason why M-pesa – the world’s biggest money system is based on USSD. There is a reason why the majority of discussion happens via SMS, but it is changing. There was an inflection point reached last year where Android devices started to penetrate to a certain level and what that has culminated in is things like Safaricom in Kenya decided that they were no longer going to sell feature phones in their stores but they were only going to sell smartphones. There are chat apps like WhatsApp and things like Mxit in South Africa which have really started penetrating the market, which means that people are using the data channel for even chatting now, meaning less direct text messaging will happen. The early indicators are that we are moving towards the data channel, therefore smartphones will penetrate.

What is the importance of a player like Google in Africa?

It’s massive. Google, Intel, Microsoft, all the big corporate tech companies, and Samsung of course. Those four in particular have had a huge impact on both the decreasing cost of the devices, decreasing cost of the data channels itself and penetration across the sector because they do some of the advertising too. So, I mean the corporate [giants] have driven this.

You work on Ushahidi as well offer Crowdmap – tools that media companies can use, when you look at media companies, how would you advise them to embrace technology?

That’s a good question and the answer is that these crowd technologies are not going away and though they are awkward to learn how to deal with, the best time to learn how to deal with it is when everybody else is learning how to deal with it as well. So get involved and try it instead of standing back and waiting for the ecosystem to develop. Be a part of that ecosystem developing instead. Get involved now.

So should they bring in hackers? There has been a lot of discussion about “hacker-thons” where journalists meet and try to work with hackers.

The answer is never to keep doing what you are doing. The answer is try something different because if you just keep doing what you are currently doing, you are going to be quickly irrelevant. So sure, reach out to the different technology groups. Reach out to do some events around technology – the hacks/hackers kind of thing for journalism and technology – that’s a really great platform.

Feedback