Reporting on climate change: Part II

Good reporting on climate change is important, and likely to become more so in the future as the impacts of changing weather patterns on lives and economies grow. But climate change journalism can be challenging. It’s complicated, controversial and there is a lot of information, and misinformation, to wade through. In part I of this two-part series, Kyle James offered tips on how to report on a changing climate. In this post, he looks some common pitfalls to avoid.

In my first post on climate change reporting, I mentioned criticism aimed at the BBC by British lawmakers for alleged shortcomings in its climate coverage. That the experienced journalists at the BBC can stumble regarding this topic (if the allegations are true) illustrates the difficulties in getting climate journalism right.

And it’s important to get it right, since climate news could well become a top story of the future. A sobering report released at the end of March by the UN’s Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) said the worst is yet to come unless big reductions are made in the amount of greenhouse gases going into the atmosphere.

Previously, I talked about the importance of reporters understanding the basics of a changing climate and the mechanisms involved. While you don’t need an advanced degree, you need to know the fundamentals to be able to tell climate stories in accessible, jargon-free language. To further ease understanding, use visuals and multimedia where you can, put a human face on it, and focus on the local context if possible. And, like in many stories, follow the money.

Now, let’s look at what you should probably avoid. Watch out for the following traps.

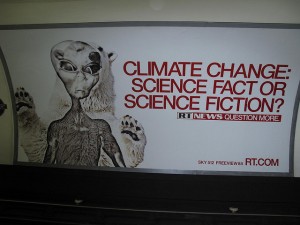

Keep away from “false balance” – In an attempt to make their stories balanced, journalists often report the views of climate-change skeptics as a counterweight to the findings of scientists. But by giving these skeptics equal weight, it gives the story a false balance.

A large majority of scientists agree broadly with the IPCC’s findings on climate change, so giving minority views the same prominence as the accepted scientific opinion is not “balance”. Whilee there’s still uncertainty, especially about regional impacts, the overall thesis of human-caused climate change is well established.

It is good to air all sorts of views, even from those who might be on the payroll of the coal industry. But it’s important to describe their credentials and whether the opinion they hold is a minority one.

That was what the UK government’s Science and Technology Committee chastised the BBC about, saying some editors were “poor” at determining viewers’ and listeners’ level of expertise and sometimes pitted lobbyists against “top scientists” as if their views had “equal weight”.

Remember, the people you quote are entitled to their own opinions but not their own facts.

Look for bias or vested interests – This is related to the tip above. That climate-change skeptic on your program might be a lobbyist working for the oil industry with a very real financial interest in seeing that nonrenewable energy industries stay strong. This can slant their views.

But it can go the other way as well. Perhaps someone in your article is explaining how the widespread installation of solar panels would be an instant solution to rising temperatures. Maybe they’re right, but maybe they work for a solar energy company who stands to profit. Be skeptical, do your research and check connections and credentials.

Resist sensationalism – Newspaper editors want to sell editions; online editors want clicks. A screaming headline can help achieve these goals.

Still, do everything in your power to avoid the temptation to sensationalize. While scientists’ sober talk of uncertainty might not be as eye-catching as a headline about a New York under water in a decade, it’s better to have an accurate story that communicates nuance than a misleading one, even if it opens the newscast.

Don’t confuse weather events with the climate – In large parts of North America, this year’s winter was long and unusually cold. It led to many pictures of icy cityscapes and captions like “Global Warming??”

Remember, climate is the average of weather over a long period of time. As such, a few extreme weather events don’t confirm, or refute, climate change. Climatologists are looking at the big picture, and their findings say that, in general, it’s getting hotter. Climate change is a non-linear process, so there will be surprises like freak periods of cold. Talk to the experts, like climatologists or weather experts, about the bigger trends.

Don’t limit your sources – Often, journalists focus their reporting on what government officials say at conferences. But it’s important to widen your scope.

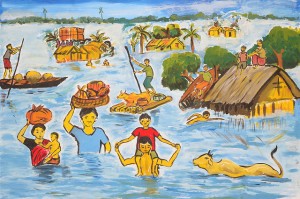

Most scientists are interested in the truth just like you are. Talk to them. In addition, include the voices of other people with a stake in the matter—which is a pretty big group since we’re talking about the Earth. Everyone from local villagers to NGOs to business leaders are good sources. They’ll all have insights from their particular perspective.

Don’t fall victim to greenwashing – As the environment has gotten more coverage, many businesses are jumping on the green bandwagon—touting supposed climate friendliness, usually in the pursuit of more profit. This is greenwashing, which the Oxford English Dictionary defines as: “Disinformation disseminated by an organization so as to present an environmentally responsible public image.”

Oil giant BP, formerly British Petroleum, once engaged in one of the biggest greenwashing campaigns I can remember with their “Beyond Petroleum” marketing blitz. It made it sound like they were moving away from oil and into renewables, but then, those BP service stations didn’t stop pumping gasoline, did they? This was greenwashing writ large.

Oil giant BP, formerly British Petroleum, once engaged in one of the biggest greenwashing campaigns I can remember with their “Beyond Petroleum” marketing blitz. It made it sound like they were moving away from oil and into renewables, but then, those BP service stations didn’t stop pumping gasoline, did they? This was greenwashing writ large.

It’s about money, marketing, self-image – rarely about the environment.

So if you see hard-to-believe claims, unknown labels that supposedly tout environmental concern, vague claims like “all natural”, “organic”, or the words “green” or “eco” thrown into a name, be wary. A paper company might use a little recycled content but is still cutting down forests. An airline might claim it’s erasing its carbon footprint but that’s most unlikely. Check it out and ask for proof.

The Greenwashing Index has a good site where they take a close look at and rate claims.

Stronger, together

So now you have a few tips on what to know, and what to avoid. Here are a few more to help you on your way to becoming a solid, responsible climate change journalist. As this story is going to get bigger, it’s very probably these skills will be in high demand.

Get connected – Join networks to share knowledge and learn from colleagues. There are a number of them, like the Earth Journalism Network or national groups. See if your country has one. Many countries also have science journalist organizations.

Sign up on sites like the Climate News Network to get climate news sent directly to your mailbox or the Guardian’s Environmental Network, a real treasure trove.

Or, think about starting your own network. At last year’s climate workshop, the participants decided to team up and build their own South Asian network, where they regularly exchange information and look at each other’s work.

Join forces with colleagues – While you might have a good grasp of the science, maybe economics is not really your thing. But to really tell the climate change story, you’ll need to understand how money is involved as well as the politics behind everything. Team up with other journalists. Each can use his or her strengths to report on different angles. You’ll have a better story than just one aspect reported on in isolation.

Written by Kyle James