Election reporting dos and don’ts – before the polls

In any country, elections are the political high point of the year. Campaigns can be drawn out or seen as a forgone conclusion for an incumbent political party or leader, but they can also be violent, dividing communities and straining stability in democratically fragile countries.

The media of course can make a pivotal contribution to whether a country’s elections are free and fair. One of its main roles is to be an accurate source of information – letting voters know about the issues, the politicians and their promises and manifestos and how the electoral system works. The media also has an watchdog role in exposing any wrongdoings. In addition, the media gives voters an important forum to express their views. In the first of our three part series on election reporting, DW Akademie’s Kate Hairsine brings you some dos and don’ts of reporting in the pre-election period.

DO know the ins and outs of the electoral process

It might sound obvious but if you are covering an election, you need to be familiar with the electoral process. Otherwise you can’t properly report on any problems or electoral malpractice. Some things you should know:

– How do voters register?

– Who is restricted from registering (non-citzens, mentally ill, prison inmates?)

– What are the rules governing the registration of candidates and have all candidates seeking to stand been able to register?

– What are the rules governing campaign financing? Is there an obligation for parties to declare finances, is there a limit to political donations, or does the state finance the campaigns of political parties?

– Where are the boundaries of electorates? Have they been recently altered without proper consultation?

– Who will impose penalties on parties or candidates who break the rules? Is this organization, such as an election commission, independent of the government? How is the management of this organization appointed?

DO be balanced in your reporting

Being balanced in reporting and programming means striving to include the voices of all main political parties and not simply one opinion. It means if a candidate makes an election promise, then you should seek reactions from other candidates and voters. People should especially have the right of reply to controversial statements. At times, it is impossible to avoid giving one party more coverage because of the significance of an event. But similar events by other parties should receive similar amounts of coverage.

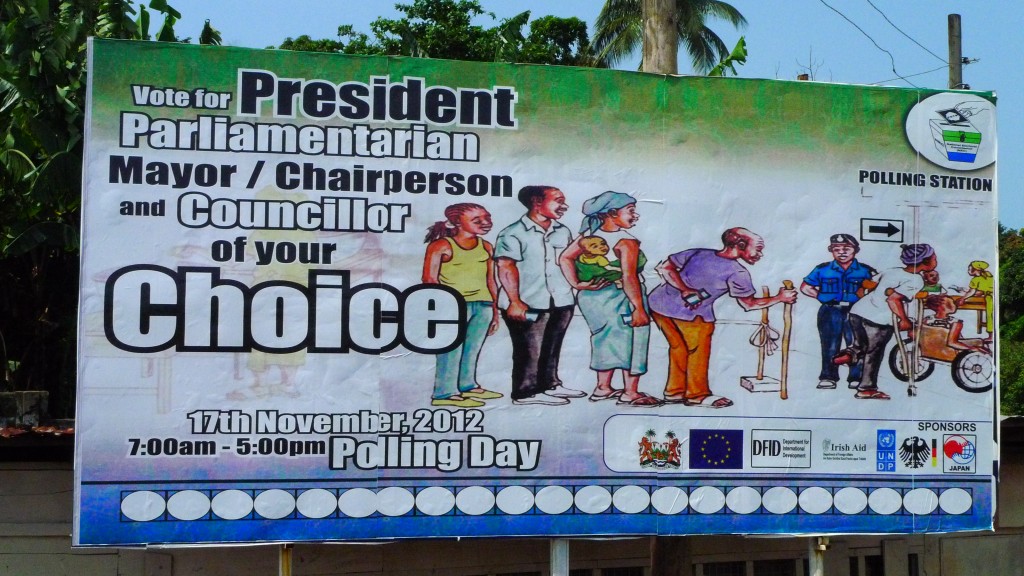

A Liberian election reporter asks a disabled woman what she thinks is the biggest issue facing her country

DO focus on the issues, not just on the politicians

Too often, election reporting is focused on politicians and their manifestos and speeches. But instead of reporting what politicians say what they will do for the people (called top-down reporting), an alternative is to find out and report on what people want from the politicians. Known as bottom-up or voters-voice reporting, the idea is to make voters heard in elections. It is also a way to help voters understand the differences between the parties and make an informed decision on election day.

– Talk to a wide range of people in your area (male, female, young, old, educated, illiterate, wealthy, poor)

– Find out what they think are the most important issues in the election

– Ask politicians from various parties what they will do about this particular issue

– If possible, talk to neutral experts/civil society groups to find out what they think could be done to help solve the problem

The excellent handbook, Media &∓ Elections has more on the topic with some examples

DO put political rallies or speeches into context

If you are reporting on a political event or speech, don’t just report on what was said. If you do that, you are simply acting as a mouthpiece for the politician. Instead, you should include details to put the event in context:

– Report where the event was held

– Make an estimate of how many people were present

– Describe what kind of people attended: Were they male, female, young, old, workers, university educated, people from a particular village or supporters offered transport?

– Ask people about their reactions to the event or speech

– Ask those present what else they would have liked to have heard or find out what issues are important to them

– Add background information about the candidate’s track record of implementing election promises

– Seek balance in your story by asking other leaders and voter groups what they think of the speech

DO report hate speech in a responsible way

Politicians often use inflammatory language and insults to attack other candidates, parties, or ethnic groups associated with a particular party. It is important to report hate speech in a responsible way so as not to incite tensions or fan ethnic violence.

– Balance your reporting of the comments with a reaction from those who are being attacked

– Try to include reactions from people on the street to the comments (in my experience, regardless of their political persuasion, many ordinary voters are outraged by hate speech)

– Seek a statement from a respected or prominent figure (imam, priest, musician, footballer, peace advocate) calling for peace

DO look at the past record of the government and the opposition

Some journalists are afraid to analyze and criticize the record of the present government for fear of being seen as in favor of the opposition. However, it is a journalist’s role to examine the achievements of government. Has it lived up to election promises? Has the government, for example, improved roads or installed a reliable power supply as it pledged to do so? Journalists need to provide this information to help people judge whether they should vote the current government back in. Don’t forget to look at what role the opposition played in the previous term. Did they present alternative ideas and suggestions? Did opposition politicians take part in constructive debates on issues?

DON’T forget to cover the smaller parties

Many elections are dominated by two main parties who receive most of the media coverage. However, in the interests of balance, try and cover the smaller parties, some of which may be of interest to certain minority groups or important in certain regions. In addition, one of the minor parties could end up in a governing coalition or hold the balance of power in parliament.

DON’T just talk to experts

In the lead up to the elections, many journalists tend to focus on interviewing experts, such as election commission officials and chiefs of police to find out how the election organization is going. While such experts have their value, they often have a vested interest in saying everything is under control.

– Don’t forget to ask relevant civil society organizations and election watchdogs to comment on election preparations

– Even better, talk to affected groups. For example, if you are going to interview an election commission official about the organization of transport on election day, visit a disabled group beforehand and see if they have been given information about how they will get to the polling booths.

– Play the resulting vox pop or a report before your expert interview, or put this information in your article. It’s not just better journalism – it also makes for more lively programming.

While party t-shirts and clothing proliferates at election time, as a journalist, your role is to be neutral

DON’T attend party rallies or wear party colors or pins in the lead up to elections

It doesn’t matter how strongly you feel about a particular politician or party, showing your political affiliations undermines your credibility as a journalist. Many people won’t talk to a reporter who is seen as siding with a certain party. And even if your reporting isn’t biased, people won’t view you as a credible source of information because they will perceive you as biased.

DON’T broadcast rumors

In many countries without a strong independent media, rumor is unfortunately one of the main sources of information. But incorrect information can fan tension and inflame violence during the election period. Don’t add to it! Always have at least two credible sources of information before reporting something.

For more information, check out UNESCO’s list of online election reporting resources

I also recommend the “Election Reporting Handbook” by the International Journalist Federation

In Part 2, Kate will take a look election reporting on the day of the polls.∓

Feedback