Unbaking Alaska?

When I first went to Alaska in 2008, “Unbaking Alaska“ was the title of the reporting project on how climate change is affecting the region and what the world might be able to do about it. I had to explain the title to my German colleagues, unfamiliar with the “Baked Alaska” dessert, while my North American and British colleagues thought it was a quirky, witty little title.

This week, when I saw an article in the Washington Post entitled “As the Arctic roasts, Alaska bakes in one of its warmest winters ever”, I found the “dessert” had become a little stale .

The thing about “Baked Alaska” is that the ice cream stays cold inside its insulating layer of meringue. Unfortunately, all the information coming out of Alaska and the Arctic in general at the moment, suggest that the ice is definitely not staying frozen.

Too hot for comfort?

In the Washington Post article, Jason Samenow refers to this winter’s “shocking warmth” in the Arctic, some seven degrees above average. Alaska’s temperature, he says, has averaged about 10 degrees above normal, ranking third warmest in records that date back to 1925. Anchorage has found itself with a lack of snow.

“This year’s strong El Nino event, and the associated warmth of the Pacific ocean, is likely partly to blame, along with the cyclical Pacific Decadal Oscillation – which is in its warm phase”, Samenow writes. Lurking in the background is that CO2 we have been pumping out into the atmosphere over the last 100 years or so.

Sea ice on the wane?

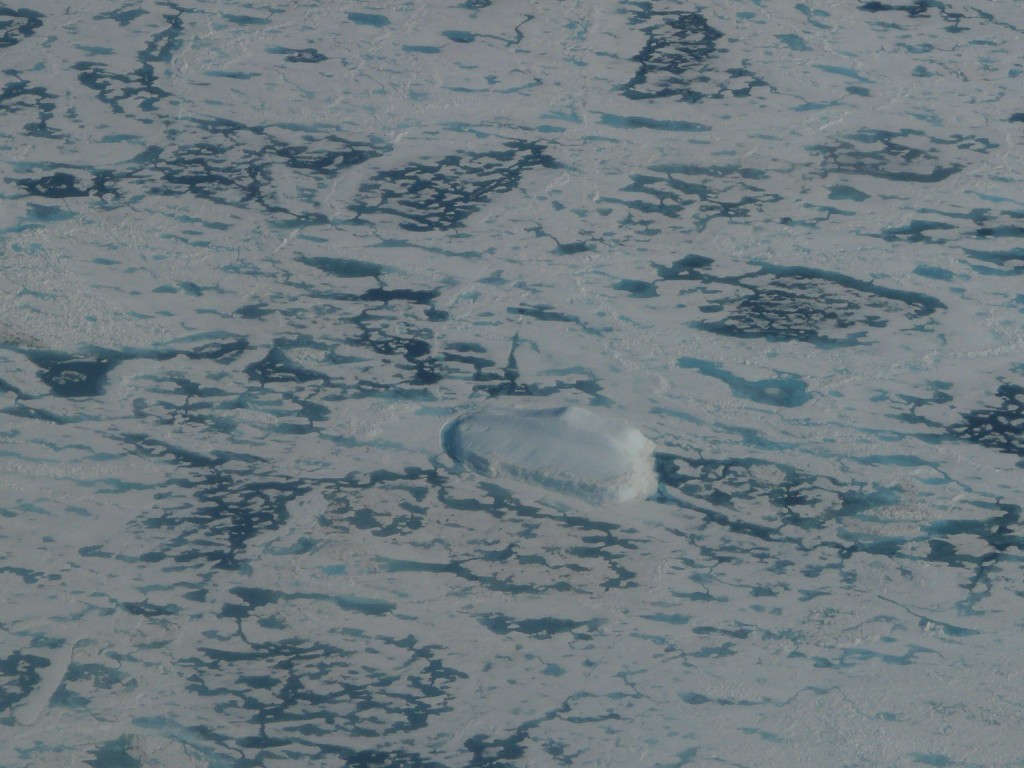

Meanwhile, the Arctic sea ice is at a record low. Normally, in the Arctic, the ocean water keeps freezing through the entire winter, creating ice that reaches its maximum extent just before the melt starts in the spring. Not this time.

Yereth Rosen wrote on ADN on Feb. 24th the sea ice had stopped growing for two weeks as of Tuesday. He quotes the NSIDC as saying the ice hit a winter maximum on February 9th and has stalled since.

“If there is no more growth, the Feb. 9 total extent would be a double record that would mean an unprecedented head start on the annual melt season that runs until fall”.

This would be the earliest and the lowest maximum ever. Normally, the ice extent reaches its maximum in early or mid-March.

The most notable lack of winter ice has been near Svalbard, one of my own favourite, icy places.

The experts say it’s too early to say whether this is “it” for this season. There is probably more winter to come. But even if more ice is able to form, it will be very thin.

Toast or sorbet?

Coming back to those culinary clichés: Samenow in the Washington post writes of the second “straight toasty winter” in the “Last Frontier”. The links below his online article are listed under “more baked Alaska”. Amongst them I find the headline: “As Alaska burns, Anchorage sets new records for heat and lack of snow” and “Record heat roasts parts of Alaska”.

The trouble comes when these catchy titles become clichés and somehow stop being quirky.

Don’t we run the risk of not doing justice to the serious threat climate change is posing to the most fragile regions of our planet? Sometimes I worry that the warming of the Arctic is becoming something people take for granted, and, even more dangerous, something we can’t do much about. At times I sense a cynicism creeping in.

I for one will be keeping my oven-baked cake and chilled ice cream separate this weekend.

Is it possible to un-bake Alaska? Food for thought.

Picture gallery on “Baked Alaska” expedition.

Rising seas culprit: ice or heat?

My attention was caught this week by a study that ascertained that thermal expansion accounts for a much greater share of sea level rise than previously thought. In fact, quite a few journalists got the message wrong. They thought the researchers had found that climate change was causing sea level rise twice as high as previously thought, which would have been quite a sensation. In fact, what the scientists actually found was that the amount of sea level rise that comes from the oceans warming and expanding has been underestimated and is probably about twice as much as previously calculated. There is a clear difference, which does not make the research – using the latest available satellite data – any less interesting.

Since two of the authors of the study are based here in Bonn, I was able to drop in on them and get them to explain their findings and the implications for our Living Planet programme. That will be broadcast in the near future. I also talked to Professor Anders Levermann from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research on the phone, to get the research findings into context.

While physicists understand the workings of thermal expansion in the oceans in general, Levermann told me there is still a lot to learn about how the heat from excess warming is transported in the ocean, which is of key importance to understanding sea level rise, amongst other things. He says the new research will help make models of future sea level rise more accurate.

The Bonn researchers explained to me how satellite technology has made huge improvements in the collection of data, especially relating to the very deep areas of the ocean, which are very difficult to reach with conventional measuring gauges. Professor Kusche told me he would like to see the results of the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, being used by governments and coastal planners, as sea level rise will affect a large number of people living in coastal areas in the not-too-distant future. Warming seas are also linked to the occurence of storms, making the findings doubly relevant to those involved in protecting coastal areas.

From an Iceblogger point of view, I was keen to know whether the knowledge about the amount of sea level rise ascribed to thermal expansion had any implications for the role played by melting ice in raising sea level. If thermal expansion is accounting for a higher share of the sea level rise, is melting ice from Greenland and Antarctica accounting for less? I put that question first to Professor Kusche.

“We think that less of the sea level rise is coming from melting ice and glaciers, that’s actually true,” he answered. He said he and his colleagues had done a very thorough re-analysis of all the measurements available over the last 12 or 13 years, “and we are pretty sure that our numbers are correct”.

Rietbroek came in that that point: “Less, but not that much less. If you look at pubished literature and estimates of glacier melting, and try to add those up, you won’t be that far away from what we get. So the melting of glaciers is not that different from what’s been found previously”, he added.

I put the same question to Professor Levermann from PIK, who runs an ice sheet model for the Antarctic and was lead author of the IPCC chapter on sea level change. He explained to me that the various contributions to sea level rise are measured and modelled separately by different teams of experts in particular fields. The models all have a wide range of possible variation. He told me there is still some uncertainty in the distribution of the “sea level rise budget” between thermal expansion, ice sheet melt, mountain glacier melt and groundwater mining. While the latest findings on thermal expansion could potentially shift the relative contributions and are important for improving models to project future sea level rise more accurately, they do not change the validity of predictions relating to the amount of ice going into the ocean.

Ultimately, Levermann says, one of the IPCC statements with the highest certainty is that sea level will continue to rise for centuries to come. He was one of the authors of yet another study published in Nature Climate Change this past week, led by Peter Clark from the Oregon State University. It affirms that our greenhouse gas emissions today produce climate change commitments for many centuries to millenia. Unless the Paris climate agreement is put into practice asap and we reach zero or negative emissions, up to 20 percent of the world’s population will find itself living in areas that may have to be abandoned.

We are, indeed, living in the Anthropocene. Recently, I interviewed a scientist who found that we have already postponed the next ice age by 50,000 years through our fossil fuel emissions. The latest sea level study indicates that the next few decades offer a brief window of opportunity to avoid increased ice loss from Antarctica and “large-scale and potentially catastrophic climate change that will extend longer than the entire history of human civilization thus far”.

Feedback