Search Results for Tag: Climate Change College

UNESCO acknowledges Arctic site

Tsá Tué, Courtesty of UNESCO

I registered that UNESCO had added 20 sites to its World Network of Biosphere Reserves during a meeting in Lima, Peru, in March. It escaped my notice, though, that one of them was in the Canadian Arctic. Thanks to @polarkatja on Twitter, I found out that Tsá Tué in Canada’s Northwest Territories was one of the new sites added to the list this year.

I have been trying to find out the background, and exactly what that means for the area and the small community of people who live there.

The area includes Great Bear Lake, which is described by UNESCO as “the last pristine Arctic lake”. I would like to know exactly what criteria are used to come to that conclusion, but have drawn a blank so far. It is the largest lake located entirely in Canada, covering an area of 12,000 square miles, on the edge of the tree line and hundreds of miles from large centres of population. It’s on the Arctic circle, and is said to be covered with ice from late November to July. (Normally, or hitherto, I should probably say. Who knows how long that will be the case with the Arctic warming so fast).

According to the brief description I found on the UNESCO website, the Taiga that covers much of the site is important to wildlife species including the muskox, moose and caribou.

The only human residents in the site are the Sahtúto’ine (The Bear Lake People), a traditional First Nation Dene Déline people (whose name means “where the water flows”). Their community of 600 is established on the western shore of the lake, where they live off harvesting and limited tourism activity.

It seems they must have been doing a fine job combining ecological and environmental concerns, which is why they have been added to the UNESCO list. It seems fair to say the sites on the list are sort of best practice examples. These are sites of global importance to both biological and cultural diversity and, together, they represent an almost full range of the planet’s ecosystems, according to the UN body.

UNESCO Biosphere Programme

UNESCO created its “Man and the Biosphere Programme” (could it perhaps be time to switch to “Humankind…?”) in the 1970s as an intergovernmental scientific programme to improve the way people in different parts of the world live with their natural environment. Biosphere reserves are supposed to be places to learn about sustainable development and reconciling the conservation of biodiversity with the sustainable use of natural resources. Not an easy task.

The total number of biosphere reserves is now at 669 sites in 120 countries, including 16 “trans-boundary” sites. New reserves are designated each year by the International Coordinating Council of the Programme, which brings together elected representatives of 34 UNESCO Member States.

Biosphere, SDGs and Paris Agreement

This year, the 4th World Congress of Biosphere Reserves ended on 17 March in the capital city of Peru with the adoption of a Declaration and a new ten-year Action Plan.The Lima Declaration sets out to promote synergies between Biosphere Reserves and the United Nations’ 2030 Sustainable Development Goals and the Agreement on Climate Change, adopted in Paris in late 2015. Clearly, none of these agreements can function in isolation.

The text recommends a “wider and more active role” for local communities in the management of the reserves and the establishment of “new partnerships between science and policy, between national and local governance, public and private sector actors.” It also calls for greater involvement of citizen groups and organizations, notably indigenous and youth communities and stresses the need for collaboration with scientific institutions such as universities and research centres. It is not hard to see that remote communities in the Arctic are a fine place to implement this.

Remote Arctic communities rely on close cooperation. (First Nation guide standing bear guard for scientists) (Pic: I. Quaile)

Remote Arctic communities rely on close cooperation. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Threat from pollution and climate change

The Deline settlement is on the Great Bear Lake, near the headwaters of the Bear River. There is an ice crossing from Deline to the winter road on the far side of the Great Bear River. It seems there was an accident there just last month (March 2016) when a tank truck fell partway through the ice road, just a few days after the government had increased the allowed maximum weight limit to 40,000 kg (88,000 lb) on the road. The truck was loaded with heating fuel for the community, and the accident close to the community’s fresh water intake as well as a major fishing area. This would seem to illustrate the problems human settlement can cause for a key nature reserve area. In fact, it was possible to remove the fuel from the truck.

In terms of sustainable economic activities, today, the lake is a popular destination for people interested in fishing and hunting. Apparently, the largest lake trout ever caught by angling was caught here in 1995. One tourism website advertises the exclusivity of the region, saying only 300 anglers are allowed to fish every year.

In the past, though, mining has been carried out in the region, with uranium, silver and copper in evidence.

As well as climate change, possible mineral, oil and gas and mining exploration put additional pressures on the Lake region, says the UNESCO designation. “Local community elders and leaders worked for many years to develop environmental stewardships,” it says. Being added to the list is an acknowledgement of their commitment, and a way of increasing awareness of the continuing need to protect the area against these threats. The Yorkton News notes that the designation does not carry any legal protection for the land or restrict local decision-makers. “Its purpose, according to the Canadian Biosphere Reserves Association, is to share best practices and make it easier to conserve ecosystems without damaging residents’ ability to make a living on them”.

My congratulations to those who have succeeded in getting the region onto the UNESCO list. And I sincerely hope it will help you continue to restrict human influence on this key area and give encouragement to all those fighting to protect the Arctic on all levels. For that, though, they would have to know about it. So, Iceblog readers, now you have heard a little about it, let’s spread the word.

Unbaking Alaska?

When I first went to Alaska in 2008, “Unbaking Alaska“ was the title of the reporting project on how climate change is affecting the region and what the world might be able to do about it. I had to explain the title to my German colleagues, unfamiliar with the “Baked Alaska” dessert, while my North American and British colleagues thought it was a quirky, witty little title.

This week, when I saw an article in the Washington Post entitled “As the Arctic roasts, Alaska bakes in one of its warmest winters ever”, I found the “dessert” had become a little stale .

The thing about “Baked Alaska” is that the ice cream stays cold inside its insulating layer of meringue. Unfortunately, all the information coming out of Alaska and the Arctic in general at the moment, suggest that the ice is definitely not staying frozen.

Too hot for comfort?

In the Washington Post article, Jason Samenow refers to this winter’s “shocking warmth” in the Arctic, some seven degrees above average. Alaska’s temperature, he says, has averaged about 10 degrees above normal, ranking third warmest in records that date back to 1925. Anchorage has found itself with a lack of snow.

“This year’s strong El Nino event, and the associated warmth of the Pacific ocean, is likely partly to blame, along with the cyclical Pacific Decadal Oscillation – which is in its warm phase”, Samenow writes. Lurking in the background is that CO2 we have been pumping out into the atmosphere over the last 100 years or so.

Sea ice on the wane?

Meanwhile, the Arctic sea ice is at a record low. Normally, in the Arctic, the ocean water keeps freezing through the entire winter, creating ice that reaches its maximum extent just before the melt starts in the spring. Not this time.

Yereth Rosen wrote on ADN on Feb. 24th the sea ice had stopped growing for two weeks as of Tuesday. He quotes the NSIDC as saying the ice hit a winter maximum on February 9th and has stalled since.

“If there is no more growth, the Feb. 9 total extent would be a double record that would mean an unprecedented head start on the annual melt season that runs until fall”.

This would be the earliest and the lowest maximum ever. Normally, the ice extent reaches its maximum in early or mid-March.

The most notable lack of winter ice has been near Svalbard, one of my own favourite, icy places.

The experts say it’s too early to say whether this is “it” for this season. There is probably more winter to come. But even if more ice is able to form, it will be very thin.

Toast or sorbet?

Coming back to those culinary clichés: Samenow in the Washington post writes of the second “straight toasty winter” in the “Last Frontier”. The links below his online article are listed under “more baked Alaska”. Amongst them I find the headline: “As Alaska burns, Anchorage sets new records for heat and lack of snow” and “Record heat roasts parts of Alaska”.

The trouble comes when these catchy titles become clichés and somehow stop being quirky.

Don’t we run the risk of not doing justice to the serious threat climate change is posing to the most fragile regions of our planet? Sometimes I worry that the warming of the Arctic is becoming something people take for granted, and, even more dangerous, something we can’t do much about. At times I sense a cynicism creeping in.

I for one will be keeping my oven-baked cake and chilled ice cream separate this weekend.

Is it possible to un-bake Alaska? Food for thought.

Picture gallery on “Baked Alaska” expedition.

Paris: A COP-out for Arctic Peoples?

As I write, the climate negotiations have been extended into Saturday. Same procedure as every year? While I still hope the seemingly never-ending bickering will result in a document which will at least signal the end of the fossil fuels era, I cannot help feeling a sense of sadness and regret, that this is all way too late for the Arctic, as I discussed in the last blog post. And I wonder how all this feels to indigenous folk living in the High North, as they see their traditional lifestyles melting away.

On a recent edition of DW’s Living Planet programme, Lakeidra Chavis reported on the effect of melting permafrost on indigenous communities in Alaska. Chatting to a colleague in between times about the story, she told me how moved she was to hear how skulls had been washed up in a river as the permafrost at a burial site thawed.

Climate change impacts the present, future – and past

I had a kind of déjà vu feeling. Back in 2008, in those early days of the Ice Blog, I travelled out to Point Barrow, the northernmost point in the USA, with archaeologist Anne Jensen. We visited the site where a village had had to be re-located because of coastal erosion, with melting permafrost and dwinding sea ice. She told me how she was called up by distraught locals in the middle of the night and asked to help recover the remains of their ancestors before they were washed into the ocean. My colleague here in Bonn was surprised to hear that I had conducted that interview back in 2008. How could this have been known at that time already, yet so little publicized?

Climate change impacts: Jensen at the site of a lost Inupiat village at Point Barrow, 2008 (Pic.: I.Quaile)

Victims or culprits?

While a lot of attention is focused (and rightly so) on the impacts on developing countries, Asia, Africa, rising sea levels, this is an issue a lot of people know very little about. In an article for Cryopolitics Mia Bennet puts her finger on an interesting aspect of all this. The Arctic indigenous peoples are living in industrialized, developed states. That gives them an interesting status, somewhere between being victims and perpetrators of climate warming.

“A discourse of victimization pervades much Western reporting on the Arctic”, she writes. A lot of people in the region tend to blame countries outside the region for climate change. She quotes a study in Nature Climate Change in which researchers found that emissions from Asian countries are the largest single contributor to Arctic warming. But she notes that gas flaring emissions in Russia and forest fires and gas flaring emissions in the Nordic countries are the second two biggest contributors. And these industries are often supported by locals, not least because of the jobs and prosperity they bring.

This brings me back to some encounters I had during that trip to Alaska in 2008 – and others since, with Inuit people employed in the oil sector. They were reluctant to accept that the industries that provided their livelihoods could ultimately be literally eroding the basis of their cultures. Russia, the USA, Canada, Norway – are all countries involved in oil and gas exploitation. Some northern regions are highly dependent on the industries which are warming the climate.

“And for their part, Arctic countries must realize that reducing emissions begins at home on the region’s heavily polluting oil platforms and gas flaring stacks – not in Paris”, says Mia Bennet.

All up to Paris?

The sad truth is that even the two-degree target – or the 1.5 currently being debated – will not have much of an impact on Arctic warming.

Mia Bennet puts it bluntly. “Regardless of whether a positive or negative outcome is reached in Paris at COP 21, it will not dramatically affect the Arctic.”

A delegation of indigenous leaders from the Arctic countries is in Paris at the talks. Both the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the Saami Council have sent delegates, with the aim of highlighting the consequences of a warming climate for the polar regions.

Council representatives are from three distinct Inuit regions: Canada, the USA and Greenland. The Chukotka region of Russia also has a substantial Inuit population, who are not directly represented in Paris, but belong to the Council. The Saami Council has representatives from Finland, Russia, Norway and Sweden. Both sets of delegates are attending as observers, without voting rights.

In a position paper, Inuit Circumpolar Council Chair Okalik Eegeesiak of Canada stresses the Inuit’s deep concern about the impacts of climate change on their cultural, social and economic health.

She describes the Arctic’s sensitive ecosystem as a “canary in the coal mine for global change”. Following that metaphor, the canary must be close to suffocating.

The Inuit representatives in Paris are appealing for stronger measures to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees C. They stress that the land and sea sustain their culture and wildlife, “on which we depend for food security, daily nutrition and overall cultural integrity”.

But ultimately, in a world where altruism seldom plays a part, it may be their other argument – the role of the Arctic in influencing the global climate system – that convinces negotiators of the need to work against global warming. With increasing knowledge and awareness of the extent to which the Arctic influences global processes and thus weather and climate all over the globe, the willingness to take measures to prevent further deterioration of the cryosphere is likely to increase. Whether it will be in time is another question. Any negotiator in Paris who has taken a brief moment off to read this – remember, we are not talking about a remote region with a small population. We are all in this together.

Farewell to ‘Last Ice’ victims in a rapidly warming world

Ice Blog readers may remember the story of the two ice researchers and polar explorers who died when they broke through unexpectedly thin ice in the Canadian Arctic earlier this year. This week I had the chance to join friends and admirers of Marc Cornelissen and Philip de Roo at a ceremony held in their home country, the Netherlands. The unusually warm November weather, with people sitting out eating ice cream, seemed oddly apt for a tribute to two people who died doing climate research.

![]() read more

read more

“Last Ice” claims lives of researchers

This post was to be about a trip I just made to St. Petersburg to talk to students and fellow journalists about reporting climate change. Instead, I am shocked and saddened to be writing of the apparent loss of one of the people whose work featured prominently in my talks there. Polar explorer and researcher Marc Cornelissen, who led our Alaskan Arctic expedition in 2008, the first to be documented on the fledgling “Ice Blog”, disappeared in the Canadian Arctic this week and is presumed drowned after breaking through unseasonably thin ice.

In workshops and discussion panels in St. Petersburg, I found myself recounting, as I often seem to do, some of my experiences during that trip. This was the expedition which strengthened my conviction that reporting on climate change in the polar regions and its relevance for the whole world had to be a main focus of my work in coming years. I have been in the Arctic many times, but somehow that trip seems to be the one I always come back to. Dutch polar explorer and researcher Cornelissen was taking a group of young Europeans to Arctic Alaska, to find out how scientists measure sea ice thickness and other parameters – and how climate change was affecting the local indigenous population. In a talk last week, while I told students and environment journalists in St. Petersburg how that group of young Europeans found out about climate change first-hand during the “Climate Change College” project, I was unaware that the charismatic leader of that trip would not be returning from his latest Arctic expedition.

Marc Cornelissen shows climate ambassadors how to drill to measure ice thickness (i.Quaile, Alaska, 2008)

“Search and rescue” becomes “recovery”

Back in Germany I opened my Ipad one morning this week to find urgent messages from two friends I first met during that Alaskan trip – one in the USA, one in Europe – telling me Marc and his colleague Philip de Roo had gone missing on their latest climate fact-finding mission in the Canadian High Arctic. Since then, the search and rescue operation has been called off, the two researchers presumed drowned.

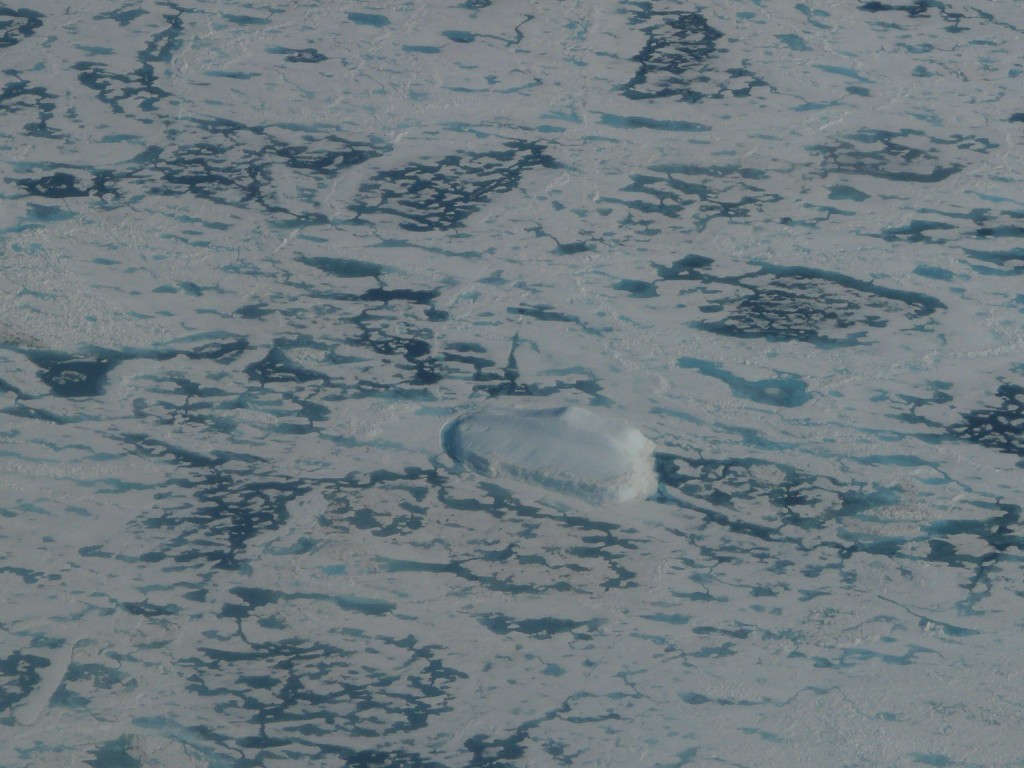

Marc, founder of the organisation Cold Facts, which supports scientific research in polar areas, was travelling on skis with his colleague, for a mission called the “Last Ice Survey“. That title was to become tragically apt in a way they had not anticipated. The two were measuring the thickness of the ice in the “Last Ice Area”,, which is thought to be the place where summer sea ice will continue longest as climate change progresses.

Arctic conditions “tropical”

In his last audio message, sent on April 28th, Marc Cornelissen, always with a great sense of humour, recounts how the weather had been so hot he had to ski in his underpants. He talks of thin ice ahead, and of the likely need to alter course to avoid it.

“We think we see thin ice in front of us, which is quite interesting, and we’re going to research some of that if we can”, Marc said in the last voice mail. Tragically, it seems that research was to prove fatal for the two curious travellers.

Next day the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Resolute Bay was alerted by a distress signal from the pair, approximately 200 kilometres soiuth of Bathurst Island. The search aircraft sighted one of their sleds, partly unpacked, on the ice with their sled dog, close to a hole in the ice. The other sled was in the water with various bits of equipment.The search and rescue venture was eventually abandoned. The dog has been rescued, but the operation to locate Marc, Philip and their equipment and bring it home, has been halted by bad weather.

The remote, cold, Arctic is a risky place to travel at the best of times. Cornelissen and de Roo were experienced polar explorers. They knew the risks. What they presumably did not know, was just how thin that “last ice” had become.

Cornelissen’s team drills to measure methane emissions from melting permafrost (I.Quaile, Denali, 2008)

Climate change is affecting the Arctic faster than any other area of the world. That was the message behind the work of the two researchers . Perhaps it was changing faster than they could have imagined.

Beautiful, fragile, perilous

I am deeply moved by the loss of these two talented and committed fellow Arctic-enthusiasts, who would still have had so much to offer the world. How ironic that the rapid ice melt they were out to document was, it seems, to claim their lives. How sad if these two had to die to underline the point.

A year and a half ago, I narrowly escaped with my life when I slipped off an icy mountain ledge in the alps. Since then, I have been more keenly aware than ever of that ambivalent nature of ice – the attraction of its beauty and the unpredictable dangers. I remember the feeling “this cannot be happening to me”, as I thought the ice I loved was throwing me to my death. I am somehow haunted by images of what Marc and Philip might have sensed in those final, precarious moments in their beloved Arctic.

Marc Cornelissen was a charismatic character, full of stories and enthusiasm for the polar regions. I remember how we laughed as he told us the tale of the “polar bear that caught me with my pants down”, during one of his expeditions. But humour and positive outlook never detracted from his concern for the safety and well-being of his charges, as he guided them onto the sea ice or frozen Arctic lakes. Cornelissen was also a motivating guide and mentor to many who have gone on to make their professions in the fields of climate, environment and sustainability.

He also had an unerring sense of the issues that would emerge ever larger in the polar climate debate in the years to come: sea ice melt, coastal erosion, melting permafrost, methane emissions.

“Everything is connected”.

Why is it I always come back to that particular Arctic trip? It is partly because it was an encounter between commited, idealistic, prosperous young Europeans, with their first climate-saving projects already in the bag, and the “locals” of Barrow, the northernmost – and so very different – settlement in the USA. These were a mixture of Inupiat traditional whale-hunters, who depended on stable sea ice to hunt – and oil workers, who owed their livelihood to the fossil fuels which are helping to melt it.

“Everything is connected” was the conclusion that dawned on the young Danish member of the group, as we stood by a visitors’ centre to look at glaciers further south – which had retreated so far, they were no longer visible from that point.

Irish “climate ambassador” Cara Augustenborg, posted her own moving tribute to Cornelissen earlier this week.

The network that was born during that Alaskan trip is still thriving. The climate ambassadors have gone on to make their ways and play their parts in the effort to understand the workings of the planet and create a low-carbon future.

For all that, you need inspiring leaders, and people who are not afraid to take on the risks of the remote, icy, unpredictable and rapidly changing Arctic. In the last personal message I got from Marc Cornelissen, he had been looking at the Ice Blog and said how pleased he was that I had “stayed with the Arctic”. Me too, Marc. And I am sorry I will never be able to interview him on what seems to have been his final expedition to the “Last Ice”.

Feedback