Search Results for Tag: permafrost

Greenland ice holds Cold War peril

It sounds like something from a science-fiction novel or a disaster movie. A hidden city under ice, housing 200 people, complete with hospital, cinema, church and research labs – and powered by a mini nuclear reactor. In fact it is reality and lies below the ice of north-west Greenland. The building of Camp Century was started in 1959, by US army engineers.

The camp was abandoned when the glacier above turned out to be shifting much faster than expected in 1967, threatening to crush the tunneled base below. Pollutants including PCBs, tanks of raw sewage and low-level radioactive coolant from the nuclear reactor were left behind.

“When the waste was deposited there, nobody thought it would get out again”, William Colgan, an assistant professor in the Lassonde School of Engineering at York University in Canada, told AFP. Colgan is co-author of a study published in August: Melting Ice could release frozen Cold War-era waste.

Unfortunately, recent research results have told us that the ice island of Greenland is melting even faster than previously thought. A new study published this week in the journal Science Advances using GPS to help estimate how much Greenland ice is melting, comes to the conclusion it is losing around 40 trillion pounds more ice a year than scientists previously thought. That is around 7.6 percent of a difference.

GPS maps past and future ice loss

Most measurements of ice sheet loss use a satellite that measures changes in gravity, and uses computer simulations to calculate the weight loss of ice. But co-author Michael Bevis of Ohio State University told the news agency AP that a portion of the mass calculated by the satellite as ice mass, is actually made up of rocks, which rise up to replace the ice when it goes. This distorts the picture, giving the impression there is more ice than there actually is.

The new study also reconstructs ice loss from Greenland over millennia and comes to the conclusion that it is the same parts of Greenland – the north-west and the south-east – which are losing most ice today as in the distant past. The authors say this means the rapid ice lost we have seen over the last 20 years is part of a long-term trend, being exacerbated by climate change. Damian Carrington in the Guardian, quotes Christopher Harig from the University of Arizona as an independent scientist not involved in the study:

“The new research happening now really speaks to the question: ‘How fast or how much ice can or will melt by the end of the century?’ As we understand more the complexity of the ice sheets, these estimates have tended to go up. In my mind, the time for urgency about climate change really arrived years ago, and it’s past time our policy reflected that urgency.”

Frozen hazards await release

Coming back to Camp Century – here, and elsewhere in the “frozen North”, a lot of the perils once locked safely inside an icy safe are now lurking ready to emerge when the time comes. Colgan led a study published in August in the journal Geophysical Research Letters, which found that higher temperatures could eventually result in toxic waste from the base being released into the environment. By 2090 the amount of ice melting may no longer be offset by snowfall, meaning the toxic chemicals could start leaking into the environment, the study found. Even before that, fissures in the snow could lead to melt water seeping into the crushed tunnels, currently located just 35 metres below the surface.

This is just one spectacular example of a problem that is widespread across the Arctic. Anthrax spores, nuclear waste from subs and reactors … and these are only the human-made dangers. The permafrost is sometimes described as a “time bomb”, with masses of methane and carbon stored as part of natural processes coming to the surface as the world warms.

The news story on AFP centres on who is responsible for cleaning up the pollution from the under-ice camp. The USA and Denmark signed a treaty to permit the construction of Camp Century, code-named “Project iceworm”. Officially, it was to provide a laboratory for Arctic research projects. AFP says it was also home to a “secret US effort to deploy nuclear missiles”. Maybe it was lucky the project had to be abandoned in 1967. But the legacy remains in the form of the nuclear waste left buried under the snow when the reactor was removed.

We have the technology, but…

Study author William Colgan believes the physical logistics of decontaminating the site may not be the biggest challenge involved in all of this. “The environmental hazard is relatively small and far away and there are only a few native towns close by”, AFP quotes.

I was shocked by this statement, which seems to imply that we don’t need to worry about “a few native towns”. I hope I have misunderstood him here. Surely the lives of these small communities should have top priority?

But I can follow his reasoning that establishing which country is responsible for making good the damage is harder than the actual physical clean-up. (He also mentions that the USA and Denmark have experience in similar clean-up operations around the Thule air base, which is around 240 toxic messes or worrying that all our technology cannot prevent destruction of the fragile Arctic environment if we carry out risky operations?)

A worrying precedent

Colgan says the dispute over responsibility “could help set a precedent for other conflicts arising from climate change”. Now that is a very worrying prospect. Unfortunately, it is also a highly realistic one.

When it comes to accepting responsibility for the climate change which is speeding up the melting of Greenland’s huge ice-sheet – and taking action to halt it by abandoning fossil fuels – conflicts are virtually pre-programmed.

When it comes to the costs of dealing with the migration of people forced out of their homes by sea-level rise, flooding, drought, and of ensuring progress for developing countries without climate-harming fossil fuels, states are unlikely to be queuing up to foot the bill.

China, USA climate pledge – all talk, no action?

Arctic interest: China maintains a research station in Ny Alesund, Spitsbergen (Pic: I.Quaile)

In a blog post earlier this year, I mused on the danger of everybody sitting back saying, “Yes, we did”, while the planet continues to break all temperature records and fossil fuel emissions continue to rise, now that all the hype surrounding the Paris Climate Agreement in December has worn off. Back to business as usual?

It’s now September and China and the USA have made the headlines telling us they are ratifying the agreements. Of course nine months (since Paris) are tiny grains of sand in the giant egg-timer of planetary evolution. (Have those egg-timers themselves been consigned to the museum in our digital 21st century? Not important). But then again, we humans have “hotted up” the pace at which our climate, planet, atmosphere, ocean are changing dramatically.

Fireworks display or starting gun?

So how do I feel about the US-Chinese announcement? I wish I could say this makes me rejoice. Sure it’s a step in the right direction. And without action by these two top climate abusers, everybody else’s efforts would basically be worthless.

The agreement must be ratified by 55 parties representing 55 percent of total global emissions to enter into force. We are now at something like 25 parties and 40 percent of emissions, which gives ground for hope the agreement could enter into force by the end of the year.

But the proof, of the pudding lies, as always, in the eating.

The drivers of change

I have been convinced for some time that crippling air pollution will drive China to move away from fossil fuels.

I think back on an interview I recorded with Chinese expert Lina Li from the Adelphi thinktank in Berlin, when she told me she thought China’s air pollution problem would speed up the country’s ratification and implementation of the Paris Agreement. You were right, Lina!

Lina Li from the Adelphi think-tank told me pollution concerns could speed up China’s climate action (Pic. I.Quaile)

As far as the USA is concerned, the outcome of the forthcoming election is clearly the key factor in determining how fast – or even whether – that country will move forward.

Doom and gloom?

Working on my Living Planet show for this week, I have been listening through reports on the Kuna people off the coast of Panama losing their island home to the waves, and how people in northwestern Kenya are starving because of changed rain patterns.

Forest fires, communities getting ready to “abandon home”, more extreme storms and flooding – these are all becoming so commonplace they are threatening to lose “news value”.

The CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is still climbing steadily. The global temperature is already one degree Celsius higher than it was at the onset of industrialization. That means very rapid action is needed to keep it to the agreed target of limiting warming to two degrees and preferably keeping it below 1.5 degrees.

A long, long way to go

Yes, the Paris Agreement was hailed widely as a breakthrough, with all parties finally accepting the need to combat climate change by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. But so far, the emissions reductions pledged would still take the world closer to a three-degree rise in temperature.

Earlier this year, the International Energy Agency (IEA), issued a warning that governments can only reach their climate goals if they drastically accelerate climate action and make full use of existing technologies and policies. I wish I could say I could see this happening fast.

In my programme this week, I also have an interview my colleague Sonya Diehn conducted with Luke Sussams, from the UK-based think tank “Climate Tracker Initiative”. That is the group that came up with the term “stranded assets” which, in turn, inspired the Divestment movement.

He explains how it makes sound economic sense to shift investment out of coal and oil and into renewables. He thinks the clear advantages – less pollution, no greenhouse gas emissions, lower costs – are the best arguments to convince developing countries to “leapfrog” the fossil fuels stage and get into green energy – and into decentralized, off-grid solutions in a big way.

It’s the economy, stupid?

It seems those economic arguments are what we need. He cites the case of Rockefeller divesting from EXXON only after years of trying to convince them to change their policy on climate change. First, he argues, we should try to change things from within. If that fails, divestment may be the next option.

At the risk of seeming cynical, I have long believed that money is the key to saving the climate. The transition to a low-carbon economy is underway, but it will only succeed when governments and companies – and ultimately also consumers – realize it benefits their coffers and their pockets.

The technology is there. I am very doubtful about whether we will manage to get emissions to peak in time for us to keep to the 1.5 degree target which scientists have me convinced is what we need to do.

It seems we will need to move on to take some of the carbon out of the atmosphere using technologies now being tested – but no way ripe enough for mass implementation. I remember a Guardian interview with IPCC chief scientist Hoesung Lee a couple of months ago. He says we can still keep to the two-degree target, even if emissions do not peak by 2020, as ex- UN climate chief Christina Figueres maintained.

But he warned the costs could be “phenomenal”. He believes expensive and controversial geoengineering methods may be necessary to withdraw CO2 from the atmosphere and store it.

Meanwhile, that giant cruise-ship, the Crystal Serenity, is half-way through its controversial trip via the Northwest Passage. The operator says the trip is so successful and interest is so high they will do it again next year. They are unlikely to be foiled by a sudden onset of global cooling.

In scientific circles, the alarm bells are ringing over rising emissions from melting Arctic permafrost.

Did somebody say something about feedback loops and tipping points? Or do we just carry on regardless?

Olympics over, but Arctic ice still chasing records

The Rio games have come to an end. Summer is drawing to a close here in Germany. It feels more like autumn today, cool with heavy rainshowers. But there’s a heatwave around the corner after what most people agree has been a very strange summer.

July followed in the record-breaking trend of the earlier months of the year, being the hottest month ever recorded on the planet.

![]() read more

read more

Why Brexit bodes ill for the Arctic

EU headquarters in Brussels. The Arctic is high on the European Union’s foreign policy agenda. The EU Council just published new Conclusions on the Arctic (Pic: I.Quaile)

Today’s Ice Blog post was going to be about permafrost, with the the International Conference on Permafrost drawing to a close after a week in Potsdam outside Berlin today. But the Brexit decision is casting a shadow over a lot of things today – and that includes the international spirit of cooperation that is the key to successfully tackling the all-embracing challenge of climate change and its destructive impacts on Arctic ice and permafrost. And while the permafrost is melting, the political atmosphere and social climate here in Europe are definitely becoming much colder.

British breakaway bad news for science

Not that the decision in itself will necessarily have a direct, immediate impact. Scientific research will go on in Britain and other parts of the world regardless of whether or not the country is a member of the European Union. The UK has a long tradition of polar exploration and research. But research relies on international cooperation – and the EU has become one of the key funders of Arctic research in recent decades.

British Arctic marine biologist collaborating with Dutch colleagues. (Ny Alesund, Spitsbergen, Pic: I.Quaile)

Leading scientists including Stephen Hawking have said a Brexit would be a disaster for UK science in general.

A group of 13 Nobel prize-winning scientists have also warned that leaving the EU would pose a “key risk” to British science. The group, which includes Peter Higgs, who predicted the existence of the Higgs boson particle, say losing EU funding would put UK research “in jeopardy”.

“Inside the EU, Britain helps steer the biggest scientific powerhouse in the world”, the group claim in a letter to the British Daily Telegraph.

While the other side insisted leaving the EU would not be damaging, the majority of scientists appear to be in favour of Britain remaining in the EU. 83% of scientists polled opposed Brexit.

International “give-and-take”

It is not just a matter of EU funding for British science. The scientist group stressed that British scientists should also be involved in the EU as a hub of innovation and research. They say more than one in five of the world’s researchers move freely within the EU boundaries.

Restricting this free movement is one of the key aims of the Brexit campaign. As a British journalist working in Germany, I have experienced the benefits of being able to travel, study and work in other European countries for many years.

Future generations bear the brunt

The majority of young people who voted apparently voted to stay in the EU. This is the generation that stands to gain or lose by the Brexit decision. If I think of all the dedicated young scientists from Britain and other countries I have interviewed over the years, working across borders on issues that are certainly not limited to one local area, it makes me sad and even angry that they stand to lose out because of a campaign that was based on negative sentiments like the desire to keep foreign workers and refugees out of Britain, or vague and unfounded claims that everything that does not work in Britain is the fault of the EU. No, it’s not perfect, but I doubt that many of the arrangements that protect nature in the UK and other European countries would be in place without the involvement of Brussels. And how is a body like the EU going to change and reform if not through pressure from within?

Anyone who cares about the environment knows that without international cooperation, it is not possible to protect our air, land, water and atmosphere against abuse and pollution.

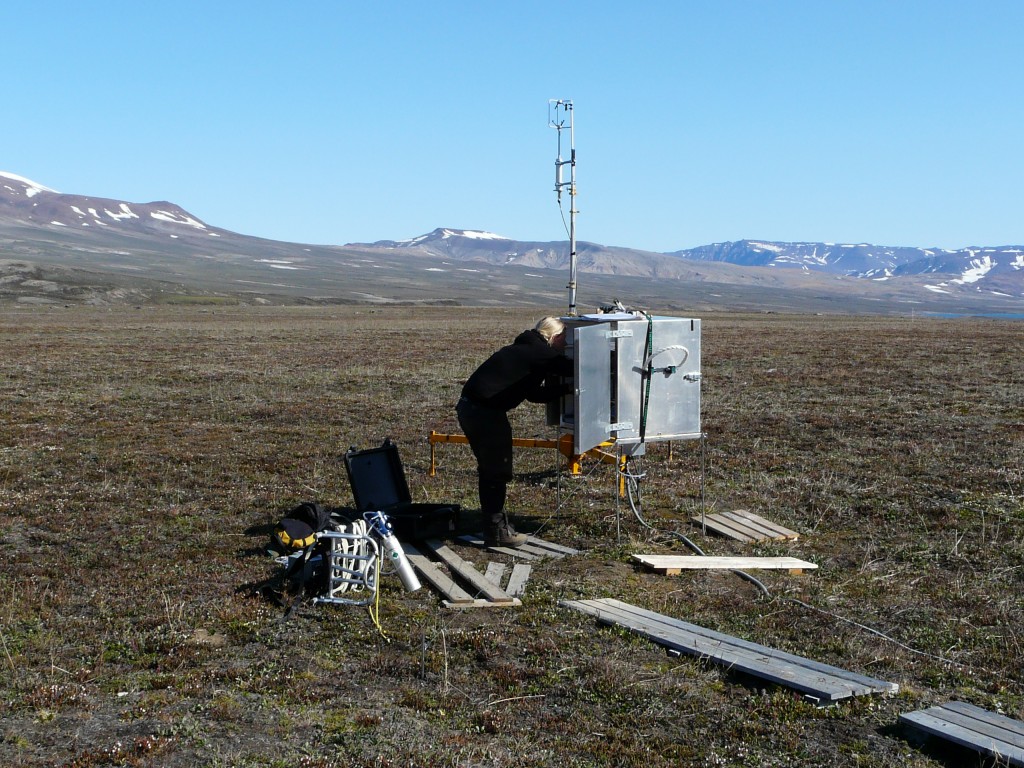

Measuring CO2 emissions from summer permafrost at Zackenberg, Greenland. GLobal emissions warm the Arctic, melting permafrost reinforces the global warming effect. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Not just about money

In an article for the MIT Technology Review, Debora MacKenzie says the EU budgeted 74.8 billion euros for research from 2014 to 2020. Brexiters, she writes, say British taxpayers should simply keep their contribution and spend it at home:

“They’d take a serious loss if they did. Britain punches above its weight in research, generating 16 percent of top-impact papers worldwide, so its grant applications are well received in Brussels. Between 2007 and 2013, it paid 5.4 billion euros into the EU research budget but got 8.8 billion euros back in grants. British labs depend on that for a quarter of public research funds, a share that has increased in recent years. A cut in that funding after Brexit could drag down every field in which British research is prominent—which is most of them.”

MacKenzie also quotes Mike Galsworthy, a health-care researcher at University College London who launched the social-media campaign Scientists for EU:

“It’s not just funding, EU support catalyzes international collaboration.” Galsworthy puts his finger on a key issue here:

“The EU funds research partly to boost European integration: for most programs you need collaborators in other EU countries to get a grant. This isn’t a bad thing, as collaborative work tends to mean more and higher-impact publications.”

Indeed.

International team measure ocean acidification off Spitsbergen, as part of EU EPOCA programme. (Pic.: I.Quaile)

One shared world

The spirit behind the vote to leave the EU is to a large extent based on nationalism and xenophobia. If it were to prevail, it would lead us backwards and result in fragmentation. That has to be bad news for those of us who believe in working together across borders for the greater good of the planet as a whole. Climate warming is a global phenomenon. We need to work together to tackle it. The icy regions of the northern hemisphere may belong geographically to individual countries like the USA, Canada, Russia or Norway. But in today’s industrialized, globalised world, no single player alone can stop the ice from melting. Or regulate the increased fishing, shipping or exploitation of natural resources in once pristine areas now becoming rapidly accessible.

Arctic future: not so permafrost

“A glance into the future of the Arctic” was the title of a press release I received from the Alfred Wegener Institute this week, relating to the permafrost landscape.

“Thawing ice wedges substantially change the permafrost landscape” was the sub-title.

“I felt the earth move under my feet…” was the song line that came to my mind.

The study was led by Anna Liljedahl of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. And Fairbanks is, indeed, where I would like to have been this past week, with Arctic Science Summit Week taking place.

Arctic Council in Fairbanks

Clearly the Arctic Council thought the same and actually managed to put their wish into practice by holding a meeting of the Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs) there from March 15th to 17th. The agenda focused to a large extent, it seems, on climate change, and “placing the Council’s overall work on climate change in the context of the COP21 climate agreement” reached in Paris in December, according to a media release.

“The Council needs to consider how it can continue to evolve to meet the new challenges of the Arctic, particularly in light of the Paris Agreement on climate change. We took some steps in that direction this week”, said Ambassador David Balton, Chair of the SAOs.

Now what exactly does that mean? The Working Groups reported “progress on specific elements”. They include the release of a new report on the Arctic freshwater system in a changing climate, “cross-cutting efforts aimed at preventing the introduction of invasive alien species”, strengthening the region’s search and rescue capacity, efforts to support a pan-Arctic network of marine protected areas and promoting “community-based Arctic leadership on renewable energy microgrids”. I suppose those could be part of the process. Clearly there are a lot of interesting things going on.

NOAA’S latest – not so cheery

Against the background of NOAA’s latest revelations on global temperature development, though, they may have to speed up the pace. The combined average temperature over global land and ocean surfaces for February 2016 was the highest for February in the 137-year period of record, NOAA reports, at 1.21°C (2.18°F) above the 20th century average of 12.1°C (53.9°F). This was not only the highest for February in the 1880–2016 record—surpassing the previous record set in 2015 by 0.33°C / 0.59°F—but it surpassed the all-time monthly record set just two months ago in December 2015 by 0.09°C (0.16°F).

Overall, the six highest monthly temperature departures in the record have all occurred in the past six months. February 2016 also marks the 10th consecutive month a monthly global temperature record has been broken. The average global temperature across land surfaces was 2.31°C (4.16°F) above the 20th century average of 3.2°C (37.8°F), the highest February temperature on record, surpassing the previous records set in 1998 and 2015 by 0.63°C (1.13°F) and surpassing the all-time single-month record set in March 2008 by 0.43°C (0.77°).

Here in Germany, the temperature was 3.0°C (5.4°F) above the 1961–1990 average for February. NOAA attributes it to a large extent to strong west and southwest winds. Now that is a big difference, and I can certainly see it in nature all around. But the difference was more than double that in Alaska. Alaska reported its warmest February in its 92-year period of record, at 6.9°C (12.4°F) higher than the 20th century average.

Why worry about wedges?

So, back to Fairbanks, or at least to the changing permafrost in this rapidly warming climate, which was on the agenda there at the Arctic Science Summit Week. (See webcast.)

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, conducted by an international team in cooperation with the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (no wonder we prefer to call them AWI), indicates that ice wedges in permafrost throughout the Arctic are thawing at a rapid pace. The first thought that springs to my mind is collapsing buildings, remembering seeing cooling systems in Greenland to keep the foundations of buildings in the permafrost frozen and so stable. Of course that only affects areas which are built upon (certainly bad enough). The new study looks at what the melting ice wedges will mean for the hydrology of the Arctic tundra. And that impact will be massive, the scientists say.

The ice wedges go down as far as 40 metres into the ground and have formed over hundreds or even thousands of years, through freezing and melting processes. Now the researchers have found that even very brief periods of above-average temperatures can cause rapid changes to ice wedges in the permafrost near the surface. In nine out of the ten areas studied, they found that ice wedges thawed near the surface, and that the ground subsided as a result. So, once more, humankind is changing what nature created over thousands of years in a very short space of time. I am reminded of a recent study indicating that our greenhouse gas emissions have even postponed the next ice age.

A dry future for the Arctic?

“The subsiding of the ground changes the ground’s water flow pattern and thus the entire water balance”, says Julia Boike from AWI, who was involved in the study. “In particular, runoff increases, which means that water from the snowmelt in the spring, for example, is not absorbed by small polygon ponds in the tundra but rather is rapidly flowing towards streams and larger rivers via the newly developing hydrological networks along thawing ice wedges”. The experts produced models which suggest the Arctic will lose many of its lakes and wetland areas if the permafrost retreats.

Co-author Guido Grosse, also from AWI, says the thaw is much more significant that it might first appear. The changes to the flow pattern also change the biochemical processes which depend on ground moisture saturation, he says.

The permafrost contains huge amounts of frozen carbon from dead plant matter. When the temperature rises and the permafrost thaws, microorganisms become active and break down the previously trapped carbon. This in turn produces the greenhouse gases methane and carbon dioxide. This is a topic already well researched, at least with regard to slow and steady temperature rises and thawing of near-surface permafrost, the authors say. But the thawing of these deep ice wedges will lead to massive local changes in patterns. “The future carbon balance in the permafrost regions depends on whether it will get wetter or dryer. While we are able to predict rainfall and temperature, the moisture state of the land surface and the way the microbes decompose the soil carbon also depends on how much water drains off”, says Julia Boike.

Now the results of the research have to be integrated into large-scale models.

The study of the impacts of thawing ice wedges seems to me like a good metaphor for the relation between Arctic climate change and what’s happening to the planet as a whole. Something changes in a localised area, which turns out to have far greater significance for a much wider area of the planet (or even the whole).

Feedback