Search Results for Tag: Svalbard

Arctic sea ice low as UN delegates talk climate in a sweltering Bonn.

Blue skies, temperature rising at UN climate headquarters in Bonn

It’s been a scorcher of a week here in Bonn. Delegates to the UNFCCC climate talks (one of the interim meetings to prepare the big COP24 which will take place in Katowice, Poland, in December) have been experiencing non-stop sunshine and temperatures up to 30 degrees Celsius. It feels like the height of summer here, although we are only at the beginning of May.

How appropriate as a backdrop to a meeting that is trying to work out the nitty gritty of actually fulfilling the Paris Agreement commitment to limiting global warming to 2 or preferably 1.5 degrees C warming.

“Currently we’re heading for 3 degrees C of warming rather than the 1.5 degrees C agreed in Paris, and the window of opportunity to reverse this is swiftly closing,” was the comment from Jens Mattias Clausen from Greenpeace Nordic.

Sea ice on the wane (again)

Coming back to work after a long break, a catch-up look at twitter, #Arctic drew my attention first to a tweet from @ArthurWyns telling me “next week it will be 20°C warmer than usual on the #Arctic!!!”

Then came one from @ketil_Isaksen, about one of my own favourite Arctic places:

“Unusually early, extensive and rapid snow melt on #Svalbard releasing extreme melt water discharges in the valleys. +6°C and strong breeze today in #Longyearbyen (78°N)”

In Arctic Today, Yereth Rosen has an article telling us this year’s Arctic sea ice melt season is “off to an unusually fast start”, and provides some worrying data from the NSIDC.

Melting ice off Svalbard (Pic I.Quaile)

Still working out the rules

Given all this, I can well understand why a lot of people involved in the talks in Bonn are feeling frustrated at the slow progress being made.

The delegates are charged with finalizing the rules for the actual implementation of the Paris Agreement. You can be forgiven if you thought things had already moved beyond that stage.

Yes, the wheels of international climate diplomacy move very slowly.

At a press briefing organized by the Climate Action Network (CAN), Li Shuo, a Senior Climate & Energy Policy Officer with Greenpeace stressed: “This is a mini Paris here. We really are trying to finalize all the detailed rules for the Paris Agreement. That’s a daunting task.”

Climate-friendly electric lorry in Bonn (assuming it’s not running on coal-powered electricity?) (I.Quaile)

The Polish dilemma

The next COP at the end of this year will be held in Katowice, the heartland of Poland’s coal industry. Wouldn’t it be fantastic if that turned out to be a turning point in the transition away from fossil fuels to renewable, climate-friendly forms of energy? The city itself says it wants to go green, as one of our correspondents reported in the latest edition of my radio show Living Planet. But, alas. There are absolutely no signs that the Polish government is planning to change its policy any time soon.

“We have seen worrying signs that the Polish presidency thinks that it will sufficient just to get some kind of rulebook,” said Alden Meyer, Director of strategy and policy for the Union of Concerned Scientists, also at the event organized by CAN.

He went on: “We don’t have to wait for the IPCC special report in October to know that what’s on the table and being implemented falls far short of what’s needed to reach the temperature goals countries agreed to in Paris.”

PLASTIC bottles, plastic cups for water? Yes, at the UN climate conference. (I.Quaile)

Coal and climate

I asked him how he saw Poland’s stance on all this at the moment. In spite of the government’s support for coal and reluctance to see to see the EU step up its goals, he stressed that “the role of the presidency is to put their domestic considerations aside and operate on behalf of the entire world community”.

Well, we can try to be optimistic.

“We retain some hope that Poland in its role as the presidency will be different from Poland in its role within the European Union and in its domestic energy policies”, said Meyer, they have to ensure that “the first review of the Paris Agreement, actually triggers much stronger climate commitments”.

Li Shuo noted that Poland was rather late in “shaping up their team” for the climate conference.

“There’s really no clarity from the incoming Polish presidency on how they plan to deal with the political process at Katowice. So we need to hear more from Poland”, he told me at our meeting.

The state of play

When I hear after a week and a half of a two-week working meeting that some progress has been made on technical issues of implementing the rules of the climate agreement, it does not make me feel confident that the international community is going to meet the emissions targets on time. “Other discussions are really stuck because of political differences”, said Li Shuo – mostly relating to the INDCs, or “nationally determined contributions”.

Concerned scientists’ representative Meyer reiterated the urgent need for progress on adaptation, with a lot of climate impacts already being felt: “No matter how successful we are on meeting the Paris temperature limitation goals, those impacts are going to continue to mount over the next several decades because of inertia and momentum in the climate system”.

A maze of science! Good to see it at the Bonn gathering. (i.Quaile)

What happens in the Arctic…

That would also apply to the Arctic region, where temperature rise is not only completely altering things for people and nature up there – it is also changing weather patterns and ocean circulation, with severe implications for the whole planet.

“What is missing is leadership and guidance, especially coming from the presidency”, said Li Shuo. And the spectre of another President is also hovering over the Bonn talks.

However, the Polish government has been preparing for the end-of-year climate extravaganza in other ways. It has passed a bill specifically for the UN summit which bans all “spontaneous gatherings” in the southern coal-mining city of Katowice between November 26 and December 16, which covers the entire period of the conference. It also submits registered participants to government surveillance and allows authorities and police to obtain, collect and use personal data of attendees without their consent or judicial oversight.

We’re still trying to get an official UNFCCC statement on that one. Good ground for getting the whole world on board to halt climate change?

Climate change is causing rapid, deeper and more extensive acidification in the Arctic Ocean

Scientists measure ocean acidification off the coast of Svalbard. (I.Quaile)

A new study reported in Nature Climate Change this week says ocean acidification is spreading rapidly in the western Arctic Ocean in both area and depth. That means a much wider, deeper area than before is becoming so acidic that many marine organisms of key importance to the food chain will no longer be able to survive there.

The study by an international team including scientists from the USA, China and Sweden, is based on data collected between the 1990s and 2010. Presumably, things have got worse rather than better since then. Unfortunately, it takes a long time for scientific research to be evaluated, reviewed and published, so current developments can easily overtake assessments which are already alarming enough in themselves. So yes, I would say this should make us sit up and listen, and lend even more urgency to the need for reducing emissions and combating climate change.

Acid bath for shellfish

Ocean acidification is a process that happens when carbon dioxide out of the air dissolves in the sea, lowering the pH of the water. This reduces the concentration of aragonite in the water, a form of calcium carbonate which shellfish and other marine organisms use to build their shells or skeletons. If the water becomes too acidic, this cannot be formed to the same extent, leaving the animals without their protective shells.

The latest published research shows that acidification is not only affecting much wider areas of the Arctic Ocean, but also that it is happening down to a much greater depth than before.

Arctic residents like shrimps like cooler water – and need calcium to form their shells. (Pic: I.Quaile, Svalbard, on board Helmer Hanssen research vessel)

Between the 1990s and 2010, acidified waters expanded northward around 300 nautical miles from the Chukchi slope off the coast of northwestern Alaska, to just below the North Pole, the scientists write. At the same time the depth of acidified waters has increased from approximately 325 feet to over 800 feet, or from 100 to 250 metres.

“The Arctic Ocean is the first ocean where we see such a rapid and large-scale increase in acidification, at least twice as fast as that observed in the Pacific or Atlantic oceans”, said Professor Wei-Jun Cai from the University of Delaware and Mary A.S. Lighthipe, Professor of Earth, Ocean and Environment at the same University. Cai is the US lead principal investigator on the project.

“The rapid spread of ocean acidification in the western Arctic has implications for marine life, particularly clams, mussels and tiny sea snails that may have difficulty building or maintaining their shells in increasingly acidified waters”, said Richard Feely, senior scientist with NOAA and a co-author.

Tiny sea snails called pteropods are part of the Arctic food web and important to the diet of salmon and herring. Their decline could affect the larger marine ecosystem.

Among the Arctic species potentially at risk from ocean acidification are subsistence fisheries of shrimp and varieties of salmon and crab.

The polar regions are suffering more than others, because cold water absorbs CO2 faster.

The icy waters of the Arctic are particularly susceptible to acidification (I.Quaile)

Less ice to hold back warm water

The acidification study published this week used water samples taken during cruises by the Chinese ice breaker XueLong (snow dragon) in the summer 2008 and 2010 from the upper ocean of the Arctic’s marginal seas, right up to the North Pole, as well as data from three other cruises going back to 1994. The data, along with model simulations, suggest that increased Pacific Winter Water, driven by circulation patterns and retreating sea ice in the summer season, is primarily responsible for the expansion of ocean acidification, according to Di Qi, the lead author of the paper.

This water from the Pacific comes through the Bering Strait and shelf of the Chukchi Sea into the Arctic basin. Melting sea ice is one factor which allows more of the Pacific water to flow into the Arctic Ocean. The Pacific Ocean water is already high in carbon dioxide and has higher acidity. As it moves north, its acidity increases further for various reasons.

The melting and retreating of Arctic sea ice in the summer months also lets Pacific water move further north than in the past.

The scientists have observed that Arctic ocean ice melt in summer used to occur only in shallow waters with depths of less than 650 feet or 200 meters. But now, it spreads further into the Arctic Ocean.

“It’s like a melting pond floating on the Arctic Ocean. It’s a thin water mass that exchanges carbon dioxide rapidly with the atmosphere above, causing carbon dioxide and acidity to increase in the meltwater on top of the seawater”, said Cai. “When the ice forms in winter, acidified waters below the ice become dense and sink down into the water column, spreading into deeper waters.”

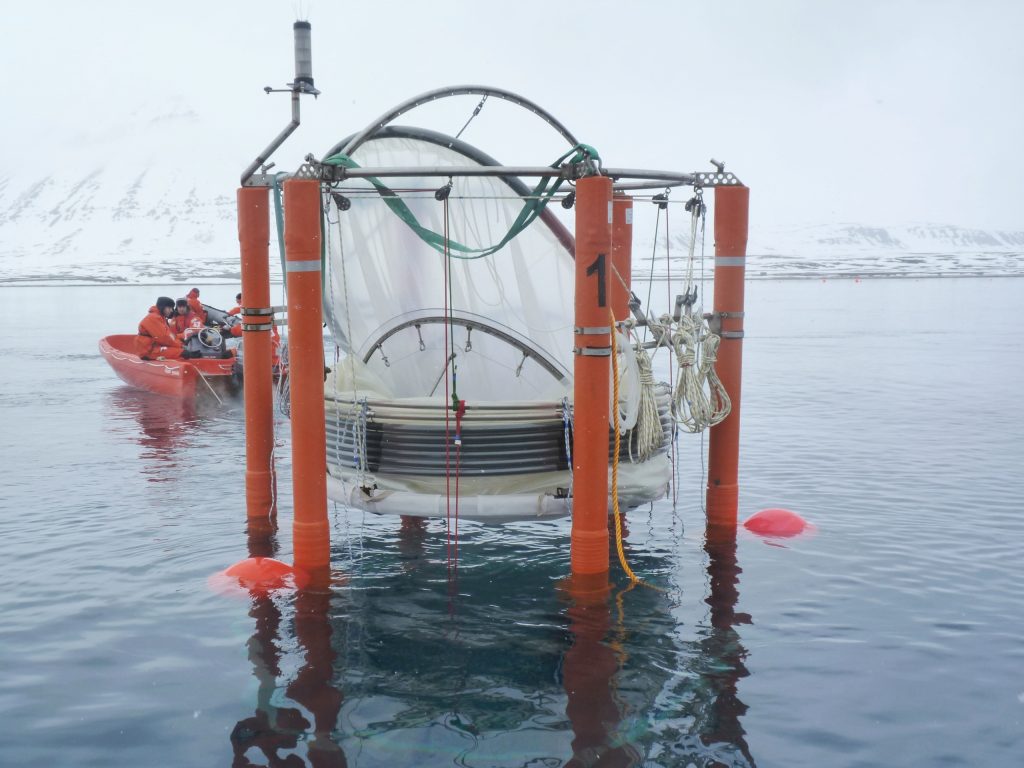

These mesocosms are used to research the effects of acidification on ocean-dwellers. (I.Quaile)

Climate chaos – not just for polar bears

In 2010, I spent some time with scientists conducting the world’s first experiments in nature, off the coast of Svalbard, to establish exactly how increasing acidification affects the flora and fauna in the Arctic Ocean.

Mesocosms, or giant test-tubes, were lowered into the sea to capture a water column with living organisms inside it. Different amounts of CO2 were added to simulate the effects of different emissions scenarios in the coming decades.

Similar experiments are still being conducted in different ocean areas. Results so far have been scary to say the least.

Mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish, coral, fish, “some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future”, Ulf Riebesell from the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, GEOMAR, told me in an interview back in 2013, when he was a lead author of a report by the International Programme on the State of the Oceans (IPSO). He was also one of the scientists in charge of that first Arctic acidification in situ experiment I witnessed back in 2010. He is currently coordinator of the German national project Biological Impacts of Ocean ACIDification (BIOACID).

Riebesell says the sea water in the Arctic could become corrosive within a few decades. “The shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve”, he told me.

Ulf Riebesell supervising the deployment of mesocosms off Svalbard. (Pic. I.Quaile)

Those feedback loops

February 27th was Polar Bear Day. Attention focused on how the decline of sea ice is having devastating impacts on those iconic creatures, who have become a key symbol of the effect of our human-induced climate change on the Arctic. Sea snails may not be quite as charismatic, but the related threat to all these tiny organisms in the water is no less worthy of our attention. Journalist Chelsea Harvey of The Washington Post writes:

“The Arctic is suffering so many consequences related to climate change, it’s hard to know where to begin anymore (…) The study highlights the interconnected nature of climate consequences in the Arctic – the way that greenhouse gas emissions, rising temperatures, ice melt and ocean acidification are all linked and help to reinforce one another. And it points to yet another example of a climate effect that’s not just a concern for the future, but is already an issue – and a growing one – today.”

Indeed, Chelsea. Climate change is already changing our lives and our planet. And, of course, what happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic. The scientists studying ocean acidification and its impacts are also concerned about a feedback effect that will further exacerbate global warming.

When the IPSO report on the state of the oceans was published, I interviewed the organisation’s scientific director Alex Rogers, a professor of conservation biology at the University of Oxford. He told me the oceans were already taking up about a third of the carbon dioxide we are producing. The report said sea water was already 26 percent more acidic than it was before the onset of the Industrial Revolution – and it could be 170 percent more acidic by 2100. In the long run, the ocean will become the biggest sink for human-produced CO2, but it will absorb it at a slower rate.

“Its buffer capacity will decrease, the more acidic the ocean becomes”, Kiel-based scientist Ulf Riebesell told me.

The IPSO report also drew a very unsettling comparison between conditions today and climate change events in the past that have resulted in mass extinctions:

“On a lot of these major extinction events we see the fingerprints of high temperatures and acidification, similar effects to the ones that we are experiencing today”.

Now there is a frightening possibility.

It is not too late to do something about this, although the experts stress the CO2 will remain in the oceans for thousands of years. The scientists tell us the key step would be to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, but also to reduce pollution and other pressures on the ocean ecosystem, which reduce its resilience. High time for the Clean Seas initiative, to reduce ocean pollution from marine litter, especially from plastic, launched this week by the United Nations Environment Programme.

“Cheers” to a cool Arctic in 2017

As 2016 draws to an end, the shortest day has passed in the northern hemisphere, and it should normally be a “cool” time of the year, in more ways than one, especially in the Arctic. But with temperatures at a record high, sea ice at a record low and feedback loops springing into action, the Arctic is hotting up – and I wish I could say the same for efforts to halt climate change.

Ice expert Jason Box tweeted this morning:

North pole near or at melting, strange given 24 h darkness there now, cold space aloft… is all about heat inflow from south @PolarPortal pic.twitter.com/r5C4i28vKR

— Jason Box (@climate_ice) December 23, 2016

Meteorologist Scott Sutherland writes on Dec. 22nd:

“(…) North Pole temperatures have climbed to 30oC hotter than normal for this time of year.

(…) Now, in late December, in the darkness of the Arctic winter, air temperatures at the North Pole have actually reached the freezing point, as recorded by weather buoys floating within a few degrees of the pole. As of the morning of Thursday, December 22 (3 a.m. EST), the International Arctic Buoy Programme (IABP), operated out of the University of Washington, recorded temperatures from these buoy up to 0oC or slightly higher.”

“(…) Right now, Arctic sea ice extent is at the lowest level ever recorded.”

Arctic in need of tlc?

It looks like the Arctic is urgently in need of some tlc – or maybe intensive care would be more fitting.

The Arctic Report Card for 2016 recently published by NOAA should have set alarm bells ringing. Based on environmental observations throughout the Arctic, it notes a 3.5 degree C increase since the beginning of the 20th century. The Arctic sea ice minimum extent tied with 2007 for the second lowest value in the satellite record – 33 percent lower than the 1981-2010 average. That sea ice is relatively young and thin compared to the past.

A “shrew”d indicator of Arctic warming

Let me quote what are described as the “Highlights”:

“The average surface air temperature for the year ending September 2016 is by far the highest since 1900, and new monthly record highs were recorded for January, February, October and November 2016.

After only modest changes from 2013-2015, minimum sea ice extent at the end of summer 2016 tied with 2007 for the second lowest in the satellite record, which started in 1979.

Spring snow cover extent in the North American Arctic was the lowest in the satellite record, which started in 1967.

In 37 years of Greenland ice sheet observations, only one year had earlier onset of spring melting than 2016.

The Arctic Ocean is especially prone to ocean acidification, due to water temperatures that are colder than those further south. The short Arctic food chain leaves Arctic marine ecosystems vulnerable to ocean acidification events.

Thawing permafrost releases carbon into the atmosphere, whereas greening tundra absorbs atmospheric carbon. Overall, tundra is presently releasing net carbon into the atmosphere.

Small Arctic mammals, such as shrews, and their parasites, serve as indicators for present and historical environmental variability. Newly acquired parasites indicate northward shifts of sub-Arctic species and increases in Arctic biodiversity. “

Getting the message across

The NOAA website sums it up in a video, saying:

“…Rapid and unprecedented rates of change mean that the Arctic today is home to and a cause for a global suite of trillion dollar impacts ranging from global trade, increased or impeded access to land and ocean resources, changing ecosystems and fisheries, upheaval in subsistence resources, damaged infrastructure due to fragile coastlines, permafrost melt and sea level rise, and national security concerns.

In summary, new observations indicate that the entire, interconnected Arctic environmental system is continuing to be influenced by long-term upward trends in global carbon dioxide and air temperatures, modulated by regional and seasonal variability.”

Margaret Williams, the managing director for WWF’s US Arctic programme had this to say:

“We are witnessing changes in the Arctic that will impact generations to come. Warmer temperatures and dwindling sea ice not only threaten the future of Arctic wildlife, but also its local cultures and communities. These changes are impacting our entire planet, causing weather patterns to shift and sea levels to rise. Americans from California to Virginia will come to realize the Arctic’s importance in their daily lives.

“The science cannot be clearer. The Arctic is dramatically changing and the culprit is our growing carbon emissions. The report card is a red flashing light, and now the way forward is to turn away from fossil fuels and embrace clean energy solutions. Protecting the future of the top of the world requires us to reduce emissions all around it.”

Sack the teacher, kill the messenger?

That was her response to the Arctic Report Card. In my school days, the report card was a business to be taken seriously. A bad report meant you were in trouble and would have to smarten up your act or you would be in big trouble with mum and dad.

The question is – who gets the report, and who has to smarten up their act?

This one should make the governments of this world speed up action on mitigating climate change and getting ready for the impacts we will not be able to halt.

Then again, they could just try to get rid of the messengers who come up with the bad news. If your kid’s report card is bad, do you try to improve his performance – or get rid of the teacher who came up with the negative assessment – based on collected data?

I am concerned that the administration in the wings of the US political stage could be more likely to do the latter. As I wrote in the last Ice Blog post, the new Trump administration is threatening to cut funding for climate research. The proposed new Cabinet is well stocked with climate skeptics.

Concern about research

Financial support for the Arctic Report Card is provided by the Arctic Research Program in the NOAA Climate Program Office. Its preparation was directed by a “US inter-agency editorial team of representatives from the NOAA Pacific marine Environmental Laboratory, NOAA Arctic Resarch Program and the US Army Corps of Engineers, Cold Regions Research and Engineering laboratory.

Yereth Rosen, writing for Alaska Dispatch News, quotes Jeremy Mathis, the director of NOAA’S Arctic research program and one of the editors of the report card.

“The report card this year clearly shows a stronger and more pronounced signal of persistent warming than in any previous year in our observational record”.

“We hope going into the future that our scientists and researchers still have the opportunity to contribute and make possible the summary that we’re able to present. So we have every intention of continuing to publish the Arctic Report Card as we have in the past and pulling together the resources and the right people that allow us to do that”.

Livid and acrimonious

The debate over President Obama’s announcement that he was making a vast area of the Arctic Ocean off-limits to drilling for oil or gas, shows the dilemma of our times – and .. which could influence the living conditions on our planet for generations to come.

Erica Martinson, writing for the Alaska Dispatch News, provides interesting insights into the debate for those of us who do not live in Alaska.

She quotes Alaska’s Republican Congressman Don Young, saying he used “livid language” in his response. Obama’s move means “locking away our resources and wuffocating our already weakened economy”. He goes on “Alaska is not and shuld not be used as the poster child for a pandering environmental agenda”.

Ooh. Livid indeed.

She also quotes Republican Senator Dan Sullivan as describing the move as “one final Christmas gift to coastal environmental elites”. So would those be the indigenous communities being forced to relocate because climate changes are destroying their homes, Senator?

The administration, on the other hand, says it is protecting the region from the risk of a catastrophic oil spill, Martinson writes.

It seems to me that Obama’s parting gift goes rather to the “Alaska Native communities of the North Slope” who “depend largely on the natural environment, especially the marine environment, for food and materials”, and to the many endangered and protected species in the area, “including bowhead and fin whales, Pacific walrus, polar bear and others”.

What about the Paris Agreement?

But as well as that regional aspect, the decision not to open up new regions to drilling for oil and gas is in line with the global need to cut fossil fuel emissions to halt the warming of the world.

Jamie Rappaport Clark, CEO of “Defenders of Widife”, puts it:

“It marks the important recognition that we cannot achieve the nation’s climate-change goals if we continue to expand oil and gas development into new, protine environments like the Arctic and Atlantic Oceans”.

This is not just about Alaska, not just about the Arctic, but the future of the planet as a whole.

The World Meteorological Organization (WMO) says 2016 is on track to be the hottest year on record. According to UN estimates, the global temperature in 2016 was 14.88 degrees C – 1.2 degrees higher than before the industrial revolution began in the mid-19th century.

In an article for the New York Times on December 22, Henry Fountain and John Schwartz quote NOAA’s Arctic Research Program director Jeremy Mathis.

“Warming effects in the Arctic have had a cascading effect through the environment” “We need people to know and understand that the Arctic is going to have an impact on their lives no matter where they live”. That includes the oil-industry-friendly and climate skeptical team that is set to enter the White House in the New Year,

So when I propose a toast to a cool Arctic in 2017, I am not just thinking of my friends in the high north. For all our sakes, we have to kick our fossil fuel habits, save energy and cut the emissions which keep the giant refrigerator that helps make our world a viable place to live well chilled.

New report sees Arctic melt on course to tip global climate

Scientists say the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard has seen such extreme warmth this year that the average annual temperature could end up above freezing for the first time on record. Ketil Isaksen of the Norwegian Meterological Institute said today the average temperature in Longyearbyen, the main settlement in Svalbard, is expected to be around 0 Celsius with a little over a month left of the year. He called the abnormal warmth “shocking” and beyond anything he could have imagined 10 years ago. The normal yearly average is minus 6.7 C.

And that is not the only shocking thing going on up north. The Arctic sea ice is melting in November. Temperatures in the region are 20 degrees Celsius above usual. Reindeer are dying across Siberia. Polar bears are stranded on land. It’s hard to keep up with the extent and speed of climate change in the far north of the planet. And we in the media have to be aware of the danger that the reports become so commonplace the “new normal” no longer arouses interest.

Svalbard’s sturdy reindeer are adapting to climate change. In Siberia, thousands of animals have died of starvation. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Warming, warming, hot

Yet the ever faster melting of our Arctic ice could spell disaster even for distant regions of the planet. What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic, as discussed here on the Ice Blog many times before. But a new, key report launched today indicates that the effects of increasingly rapid Arctic warming could be set to push global climate change out of control.

The Arctic Resilience Assessment (ARA) is an Arctic Council project led by the Stockholm Environment Institute and the Stockholm Resilience Centre. It is based on collaboration with Arctic countries and Indigenous Peoples in the region, as well as several Arctic scientific organizations. The ARA (previously Arctic Resilience Report) was initiated by the Swedish Ministry of the Environment as a priority for the Swedish Chairmanship of the Arctic Council (May 2011 to May 2013) and is being presented under the US Chairmanship. It aims to synthesize knowledge on Arctic change and how people and the ecosystem are coping with it, bringing the wide range of different factors together.

“Environmental, ecological, and social changes are happening faster than ever in the Arctic, and are accelerating. They are also more extreme, well beyond what has been seen before. This means the integrity of Arctic ecosystems is increasingly challenged, threatening the sustainability of current ways of life in the Arctic and disruption of global climate and ecosystems”, the report says.

Beyond the tipping point

The researchers issue a stark warning: “Some changes are so substantial (and often abrupt), that they fundamentally alter the functioning of the system: an ecological “tipping point” has been crossed. The report examines 19 of these “tipping points” or “regime shifts”, as they are also known: “They affect many ecosystem services that are important to people within and outside the Arctic: from regulating the climate, to providing sustenance (e.g. through fishing)”, the experts tell us.

“The consequences of some of these shifts are likely to be surprising and disruptive – particularly when multiple shifts occur at once. By altering existing patterns of evaporation, heat transfer and winds, the impacts of Arctic regime shifts are likely to be transmitted to neighbouring regions such as Europe, and impact the entire globe through physical, ecological and social connections”, the report says.

The tipping points discussed in the report include the replacement of white ice and snow, which reflect heat back into space, by darker green vegetation or ocean water, which absorbs more heat, higher releases of methane and changes to ocean circulation and so weather patterns around the globe caused by an influx of melting snow and ice.

Major impacts inevitable?

Johan Rockström, director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre and co-chair of the five-year study said in a statement: “If multiple regime shifts reinforce each other, the results could be potentially catastrophic.… The variety of effects that we could see means that Arctic people and policies must prepare for surprise. We also expect that some of those changes will destabilize the regional and global climate, with potentially major impacts”.

The report stresses that many of the changes and feedback effects in process are poorly understood and in need of much more research.

“Arctic ecological protection is now a global concern, and worldwide monitoring is inadequate”, the authors write.

Political “regime shift”?

To reduce the risk of these tipping points, strong action would have to be taken to mitigate climate change, the authors conclude. Aha. Now there’s the rub.

In the Guardian, Fiona Harvey notes the report comes at a critical time in politics, with Donald Trump’s announcement this week that he plans to take away NASA’s budget for climate science and put it into space exploration. She quotes Marcus Carson of the SEI, co-editor of the report:

“That would be a huge mistake…It would be like ripping out the aeroplane’s cockpit instruments while you are in mid-flight”.

If Mr. Trump also makes good his pledge to revive the US coal industry and abandon the Paris Climate Agreement, the chances of halting warming and the climate feedback mechanisms which could spell disaster would seem to be melting away along with that Arctic ice. Not so tasty food for thought this weekend. Well, I could distract myself by getting out the lawnmower. It has been so warm here this week the birds are chirping like spring and the grass has started to grow again.

Alpine ice – no more than a memory? New archive of ice cores

Alpine glacier – endangered species? (Pic: I.Quaile)

It was with mixed feelings that I read an article drawn to my attention by a colleague earlier in the week.

“Protecting Ice Memory” is the subject –a description of a new project to create a “global archive of glacial ice for future generations”.

I am generally enthusiastic about all projects concerning ice. The worrying thing is the reason why this project has been deemed necessary.

History melting

“The goal is to build the world’s first library of ice archives extracted from glaciers which are threatened by global warming”. There we have it. Another frightening acknowledgement of the extent and speed of global change.

How sad that our human-induced warming is threatening our ice, especially here in the European Alps, where we do not have as much ice as in some other parts of the globe. How good that we have the technology to save some of it for posterity. How frustrating that while we also have the technology to shift to a zero-carbon economy and stop the ice melting, we are not actually doing it anything like fast enough.

Starting on Monday August 15th and carrying on until early September, an international team of glaciologists and engineers (French, Italian, Russian and American) will be travelling to Mont Blanc, in particular to the “Col du Dome” glacier area, which is 4,300 metres or 14,108 feet up. They will be drilling the first ice cores for the “Protecting Ice Memory” project.

Some glaciers are being covered in summer to stop them melting, this one I saw in Switzerland. Proved ineffective. (I.Quaile)

Saving the cores

The team will be coordinated by Patrick Ginot from the French Research Institute for Development (IRD), working within the UGA-CNRS Laboratory of Glaciology and Environmental Geophysics (LGGE), and Jerome Chappelaz, director of Research at the CMRS and working within ths same laboratory.

The team will be extracting three ice cores each 130 metres long. These will be taken down by helicopter and taken to the LGGE in Grenoble. Clearly they will have to kept very cold during the process.

In 2019 (why only then, I wonder?), one core will be analysed to start a database which is ultimately to be made available to the whole world scientific community.

The other two will be transported by ship to ANTARCTICA. Yes, you read correctly. There, they will be taken on tracked vehicles across the high plateaus to be stored at the Concordia station, which is run by the French Paul-Emile-Victor Polar Institute (IPEV) and its Italian partner, the National Antarctic Research Programme (PNRA)

In the long term, dozens of ice cores are to be stored in a snow cave at -54° Celsius, which the project describes as “the most reliable and natural freezer in the world”.

The Mont Blanc glacier is the first step. The next will be carried out in 2017 on the Illimani glacier in the Bolivian Andes.

Global operation

It seems other countries with access to glaciers are also hoping to join the project, including Germany, Austria, Switzerland, Brazil, the USA, Russia, China, Nepal and Canada. That sounds like a real mega-project.

I have commented often enough here on the Ice Blog on the dwindling ice in my own favourite hiking territory in the German and Swiss Alps. Last week it was the turn of the New Zealand Alps to be the focus of this rather sadly motivated attention.

The scientists who came up with the project had the idea after observing a rise in temperatures on several glaciers. At ten year intervals, they say the temperature near the glaciers on the Col du Dome and Illimani in the Andes has risen between 1.5 degrees and 2 degrees (Those figures sound familiar from somewhere…)

“At the current rate, we are forecasting that their surface will undergo systematic melting over the summer in the next few years and decades. Due to this melting and the percolation of meltwater through the underlying layers of snow, these are unique pages in the history of our environment which will be lost forever”, says the project description.

The scientists compare their project to the Svalbard Global Seed Vault on the Norwegian Arctic island of Spitsbergen. Before I read that part, this very comparison had already come to my mind. I had a rare opportunity to visit that vault a couple of years ago.

Svalbard to Antarctica

But one of the very worrying things in that connection is that even that “secure coldspot” has in turn been affected by permafrost melt – at least at a level close to the surface, which caused damage to the entrance area in the early stages.

Will the Svalbard vault ultimately have to be moved to the even colder Antarctic at some point in the future, one might wonder?

I remember a visit to the Alfred-Wegener Institute in Bremerhaven, Germany’s polar agency. One of the highlights was a look into the laboratory where ice cores are processed. Clearly, these provide invaluable evidence of how our planet and life on it have developed. Climate and environmental archives of a quite unique nature.

“Our generation of scientists, which bears witness to global warming, has a particular responsibility to future generations. That is why we will be donating these ice samples from the world’s most fragile glaciers to the scientific community of the decades and centuries to come, when these glaciers will have disappeared or lost their data quality”, says Carlo Barbante, the Italian project initiator and Director of the Instutite for the Dynamics of Environmental Processes – CNS, Ca’Foscari University of Venice”. What a sobering thought – and a daunting task.

And what an inspiring campaign to rescue what it seems we will not be able to save in time in the natural world.

Projects like this cost a lot of money. It is relying on private sponsors. The current European project has funding. The Université Grenoble Alpes foundation is now running a campaign to fund the Bolivian expedition.

Here’s hoping the money will be forthcoming.

And here’s hoping the international community will speed up efforts to halt global warming before we have to create archives to try to document all the ecosystems, species and habitats we are losing faster than we can count them.

Feedback