Search Results for Tag: AWI

Greenland earthquake and tsunami – hazards of melting ice?

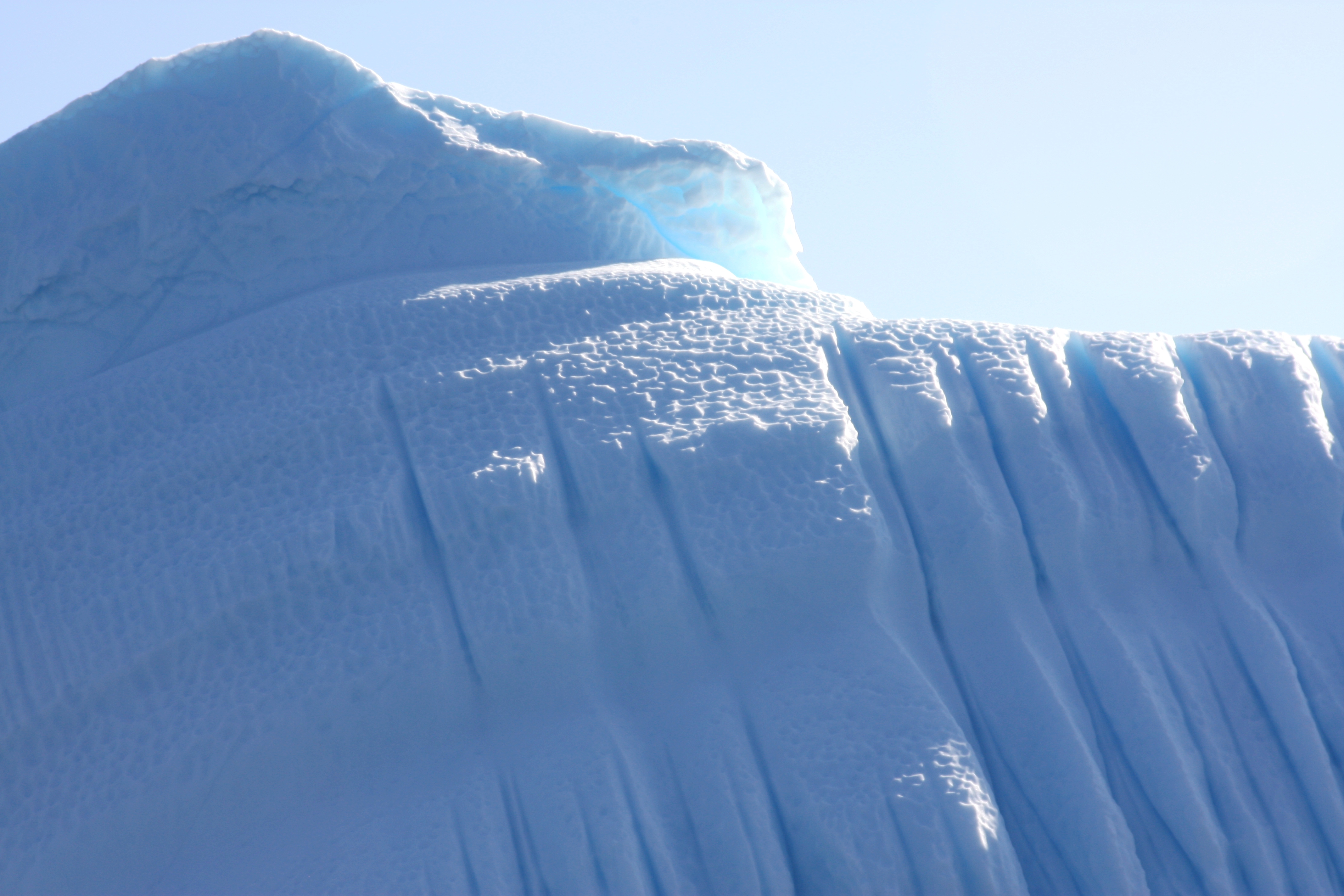

Is gradual CO2 increase speeding up Greenland ice sheet melt? (Pic: I.Quaile)

Following the news over the weekend with a trip to Greenland this summer at the back of my mind, my attention was immediately caught by reports of a tsunami and earthquake in Greenland. Four people were reported missing. Buildings had been swept away, including the power station on the island of Nuugaatsiaq. Greenland is not the first place that comes to mind in connection with earthquakes and tsunamis. But in fact they are not as rare as you might think.

The cause of the weekend’s event is still unclear. But a tweet from the Greenland Climate Research Centre links to an article in the Washington Post from June 25 2015:

“Glacial earthquakes”

The article reports on a paper published in the journal Science at that time by researchers from Swansea University in the UK, the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University and several other institutions. It says the loss of Greenland’s ice can generate “glacial earthquakes”.

“When vast icebergs break off at the end of tidal glaciers, they tumble in the water and jam the glaciers themselves backwards. The result is a seismic event detectable across the Earth”.

Worrying reading indeed, as GCRC wrote in their tweet.

The Washington Post article quoted Meredith Nettles from Columbia, one of the co-authors.

She specifically mentions the tsunami effect:

“The tsunami is caused because the iceberg has to move a lot of water out of the way as it tips over”.

Arctic icebergs can displace a lot of water (Pic: I.Quaile, Greenland)

Too early to say

I have been trying to find more information on what the experts think caused this weekend’s particular event. So far, there is no clarity. But the GCRC tweet with link to the Washington Post article seems to indicate they think it could be ice-related.

Another theory is that the quake and tsunami were caused by a landslide. The news agency DPA says the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland are still trying to determine the cause of the tsunami.

“Initially, geologists believed it was triggered by an earthquake, but another theory blamed a large landslide from one of the mountains on the fjord system”.

It seems the Danish Arctic Commando published images showing signs of an extensive landslide.

“Tsunamis and large waves at times affect Greenland’s coasts, but, according to the Geological Survey, they are usually caused by landslides and the breaking off of ice from melting glaciers”, the agency writes.

DPA earlier noted that the Danish earthquake authority GEUS had recorded a 4.0 quake.

Warning from Greenland ice cores

One way or other, the weekend tsunami is unlikely to allay anxiety about the effects of rapidly melting substantial quantities of ice.

And a study just published by Germany’s Alfred-Wegener-Institute (AWI) provides more food for thought about human-induced changes to our climate. It indicates that the gradual nature of the changes we are making to the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is no guarantee that the resulting climate change will also be gradual. On the contrary. Computer models based on information from ice cores from Greenland show that in high latitudes of the northern hemisphere, there were abrupt changes in climate, which the scientists attribute to a gradual increase in CO2.

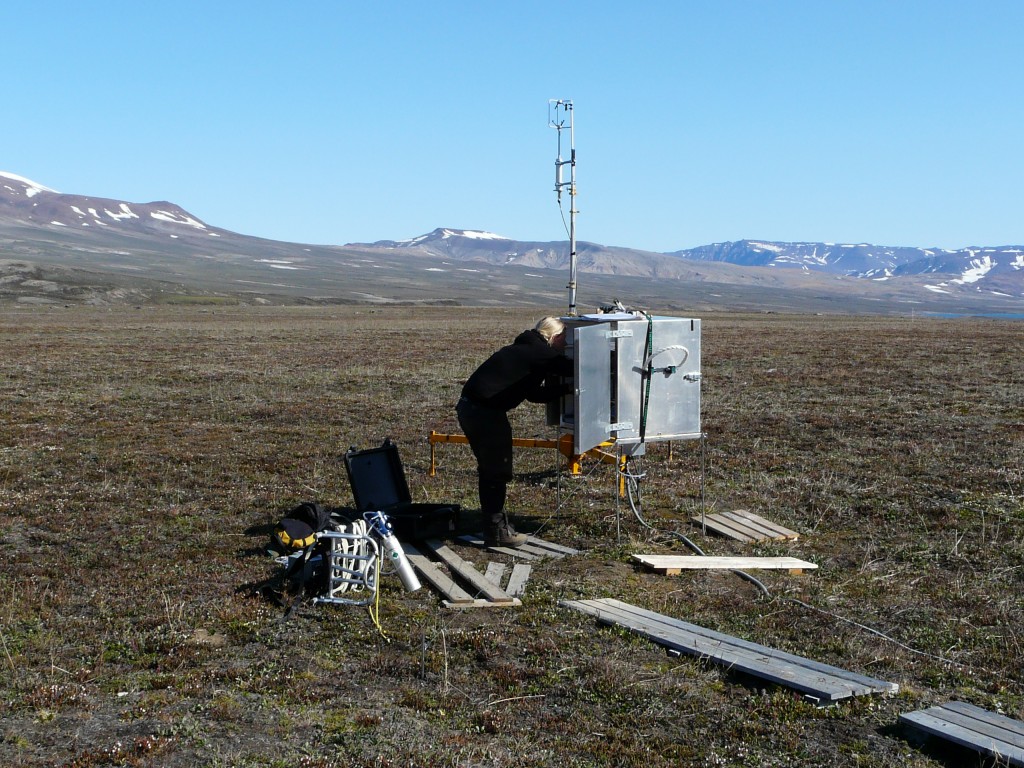

Rising CO2 emissions – no part of the world is spared (Measuring station on Svalbard, Pic. Quaile)

During the last ice age, they say that the influence of atmospheric CO2 on the North Atlantic Current within a few decades led to an increase in temperature of up to 10 degrees Celsius in Greenland. The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, by scientists from AWI and the University of Cardiff shows that in recent earth history, there have been situations when gradual increases in CO2 concentrations at what are known as “tipping points” led to abrupt changes in ocean circulation and climate.

Sudden warm age on the horizon?

Lead author Xu Zhang says the study is the first to prove that a gradual increase in CO2 can set off very rapid warming, based on interactions between ocean currents and the atmosphere.

The authors also show that the rise in CO2 is the main cause of chances in ocean currents during the transition from an ice age to a warm period.

Of course, they add, the framework conditions today are different from those during an ice age, so it is not possible to say the rise in CO2 will have similar effects in future.

But they say they can definitely show that there were abrupt climate changes in Earth’s history, which can be traced back to continual rises in CO2 concentrations.

Reason enough for concern to people living on the coast of Greenland – not to mention the rest of us, given the key role the world’s biggest island, with the biggest freshwater mass in the northern hemisphere sitting on top of it in the form a giant ice sheet, plays in influencing climate and sea levels around the globe?

Happy Birthday Koldewey Station

25 years ago, Germany set up its own Arctic research station in the tiny settlement of Ny Alesund, in the Svalbard archipelago.

Today, 11 countries run research stations there. Arctic research is a very international operation, and countries share the facilities available in Ny Alesund, one of the northernmost settlements in the world. Germany and French now run a joint station, known as the AWIPEV station, after the polar institutes of the two countries. The rest is in this picture gallery, which I put together to mark the station’s “silver jubilee”. It combines pictures from several visits I made to the station in recent years and some background about what happens up there in the “high north”.

25 years of German research in the Arctic.

View from Mount Zeppelin over the Kongsfjord, Svalbard, above Ny Alesund research village. (Pic. I.Quaile)

Arctic future: not so permafrost

“A glance into the future of the Arctic” was the title of a press release I received from the Alfred Wegener Institute this week, relating to the permafrost landscape.

“Thawing ice wedges substantially change the permafrost landscape” was the sub-title.

“I felt the earth move under my feet…” was the song line that came to my mind.

The study was led by Anna Liljedahl of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. And Fairbanks is, indeed, where I would like to have been this past week, with Arctic Science Summit Week taking place.

Arctic Council in Fairbanks

Clearly the Arctic Council thought the same and actually managed to put their wish into practice by holding a meeting of the Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs) there from March 15th to 17th. The agenda focused to a large extent, it seems, on climate change, and “placing the Council’s overall work on climate change in the context of the COP21 climate agreement” reached in Paris in December, according to a media release.

“The Council needs to consider how it can continue to evolve to meet the new challenges of the Arctic, particularly in light of the Paris Agreement on climate change. We took some steps in that direction this week”, said Ambassador David Balton, Chair of the SAOs.

Now what exactly does that mean? The Working Groups reported “progress on specific elements”. They include the release of a new report on the Arctic freshwater system in a changing climate, “cross-cutting efforts aimed at preventing the introduction of invasive alien species”, strengthening the region’s search and rescue capacity, efforts to support a pan-Arctic network of marine protected areas and promoting “community-based Arctic leadership on renewable energy microgrids”. I suppose those could be part of the process. Clearly there are a lot of interesting things going on.

NOAA’S latest – not so cheery

Against the background of NOAA’s latest revelations on global temperature development, though, they may have to speed up the pace. The combined average temperature over global land and ocean surfaces for February 2016 was the highest for February in the 137-year period of record, NOAA reports, at 1.21°C (2.18°F) above the 20th century average of 12.1°C (53.9°F). This was not only the highest for February in the 1880–2016 record—surpassing the previous record set in 2015 by 0.33°C / 0.59°F—but it surpassed the all-time monthly record set just two months ago in December 2015 by 0.09°C (0.16°F).

Overall, the six highest monthly temperature departures in the record have all occurred in the past six months. February 2016 also marks the 10th consecutive month a monthly global temperature record has been broken. The average global temperature across land surfaces was 2.31°C (4.16°F) above the 20th century average of 3.2°C (37.8°F), the highest February temperature on record, surpassing the previous records set in 1998 and 2015 by 0.63°C (1.13°F) and surpassing the all-time single-month record set in March 2008 by 0.43°C (0.77°).

Here in Germany, the temperature was 3.0°C (5.4°F) above the 1961–1990 average for February. NOAA attributes it to a large extent to strong west and southwest winds. Now that is a big difference, and I can certainly see it in nature all around. But the difference was more than double that in Alaska. Alaska reported its warmest February in its 92-year period of record, at 6.9°C (12.4°F) higher than the 20th century average.

Why worry about wedges?

So, back to Fairbanks, or at least to the changing permafrost in this rapidly warming climate, which was on the agenda there at the Arctic Science Summit Week. (See webcast.)

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, conducted by an international team in cooperation with the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (no wonder we prefer to call them AWI), indicates that ice wedges in permafrost throughout the Arctic are thawing at a rapid pace. The first thought that springs to my mind is collapsing buildings, remembering seeing cooling systems in Greenland to keep the foundations of buildings in the permafrost frozen and so stable. Of course that only affects areas which are built upon (certainly bad enough). The new study looks at what the melting ice wedges will mean for the hydrology of the Arctic tundra. And that impact will be massive, the scientists say.

The ice wedges go down as far as 40 metres into the ground and have formed over hundreds or even thousands of years, through freezing and melting processes. Now the researchers have found that even very brief periods of above-average temperatures can cause rapid changes to ice wedges in the permafrost near the surface. In nine out of the ten areas studied, they found that ice wedges thawed near the surface, and that the ground subsided as a result. So, once more, humankind is changing what nature created over thousands of years in a very short space of time. I am reminded of a recent study indicating that our greenhouse gas emissions have even postponed the next ice age.

A dry future for the Arctic?

“The subsiding of the ground changes the ground’s water flow pattern and thus the entire water balance”, says Julia Boike from AWI, who was involved in the study. “In particular, runoff increases, which means that water from the snowmelt in the spring, for example, is not absorbed by small polygon ponds in the tundra but rather is rapidly flowing towards streams and larger rivers via the newly developing hydrological networks along thawing ice wedges”. The experts produced models which suggest the Arctic will lose many of its lakes and wetland areas if the permafrost retreats.

Co-author Guido Grosse, also from AWI, says the thaw is much more significant that it might first appear. The changes to the flow pattern also change the biochemical processes which depend on ground moisture saturation, he says.

The permafrost contains huge amounts of frozen carbon from dead plant matter. When the temperature rises and the permafrost thaws, microorganisms become active and break down the previously trapped carbon. This in turn produces the greenhouse gases methane and carbon dioxide. This is a topic already well researched, at least with regard to slow and steady temperature rises and thawing of near-surface permafrost, the authors say. But the thawing of these deep ice wedges will lead to massive local changes in patterns. “The future carbon balance in the permafrost regions depends on whether it will get wetter or dryer. While we are able to predict rainfall and temperature, the moisture state of the land surface and the way the microbes decompose the soil carbon also depends on how much water drains off”, says Julia Boike.

Now the results of the research have to be integrated into large-scale models.

The study of the impacts of thawing ice wedges seems to me like a good metaphor for the relation between Arctic climate change and what’s happening to the planet as a whole. Something changes in a localised area, which turns out to have far greater significance for a much wider area of the planet (or even the whole).

Record permafrost erosion in Alaska bodes ill for Arctic infrastructure

At Point Barrow, the northernmost point in the USA, a whole village was lost to erosion (Pic: I.Quaile)

Sitting in my office on the banks of the river Rhine, I am trying to imagine what would happen if the fast-flowing river was eating into the river bank at an average rate of 19 metres per year. It would not belong before our broadcasting headquarters, the UN campus tower and the multi-story Posttower building collapsed, with devastating consequences.

Fortunately, Bonn is not built on permafrost, so we don’t have that particular concern.

Record erosion on riverbank

The record erosion German scientists have been measuring in Alaska probably hasn’t been making the headlines because it is happening in a very sparsely populated area, where no homes or important structures are endangered.

Nevertheless, it certainly provides plenty of food for thought, says permafrost scientist Jens Strauss from the Potsdam-based research unit of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI). He and an international team have measured riverbank, erosion rates which exceed all previous records along the Itkillik River in northern Alaska. In a study published in the journal Geomorphology, the researchers report that the river is eating into the bank at 19 metres per year in a stretch of land where the ground contains a particularly large quantity of ice.

“These results demonstrate that permafrost thawing is not exclusively a slow process, but that its consequences can be felt immediately”, says Strauss.

With colleagues from the USA, Canada and Russia, he investigated the river at a point where it cuts through a plateau, where the sub-surface consists to 80 percent of pure ice and to 20 percent of frozen sediment. In the past, the ground ice, which is between 13,000 and 50,000 years old, stabilized the riverbank zone. The scientists, who have been observing the location for several years, demonstrated that the stabilization mechanisms fail if two factors coincide. That happens when the river carries flowing water over an extended period, and where the riverbank consists of steep cliff, which has a front facing south, and is thus exposed to a lot of direct sunlight.

Minus 12C average no safeguard

The warmer water thaws the permafrost and transports the falling material away, and in spite of a mean annual temperature of minus twelve degrees Celsius, summer sunlight makes it warm enough to send lumps of ice and mud flowing down the slope, according to Michail Kanevskixy from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, lead author of the study.

Overall, between 2007 and 2011, the cliff – which is 700 metres long and 35 metres high – retreated up to 100 metres, resulting in the loss of 31,000 square metres of land area. That is a large area, around 4.3 football fields, the scientists calculate.

In August 2007, they also witnessed how fissures formed within a few days, up to 100 metres long and 13 metres deep.

“Such failures follow a defined pattern”, says Jens Strauss. “First, the river begins to thaw the cliff and scours an overhang at the base. From here, fissures form in the soil following the large ice columns. The block then disconnects from the cliff, piece by piece, and collapses”.

Infrastructure under threat

Although these spectacular events happened far from populated areas and infrastructure, the magnitude of the erosion gives cause for much concern, given the rate at which temperatures are increasing in the Arctic. The scientists want their information to be used in the planning of new settlements, power routes and transport links. They also stress that the erosion impairs water quality on the rivers, which are often used for drinking water.

But what about those areas of the High North where there are settlements and key infrastructure? Russia is starting to get very worried about the effects of increasing permafrost erosion.

Last month the country’s Minister of Natural Resources, Sergey Donsjkoy, expressed grave concern. The Independent Barents Observer quoted the Minister as saying, in an interview with RIA Novosti, he feared the thawing permafrost would undermine the stability of Arctic infrastructure and increase the likelihood of dangerous phenomena like sinkholes. Russia has important oil and gas installations in Arctic regions. Clearly, any damage would have considerable economic implications. There are also whole cities built on permafrost in the Russian north.

System to cool the foundations of a building on permafrost in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland (pic: I.Quaile)

High time to adapt

In 2014, I interviewed Hugues Lantuit, a coastal permafrost geomorphologist with the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, about an integrated database on permafrost temperature being set up as an EU project. He told me it would be very hard to halt this permafrost thaw, and stressed that permafrost underlies 44 percent of the land part of the northern hemisphere.

“The air temperature is warming in the Arctic, and we need to build and adapt infrastructure to these changing conditions. It’s very hard, because permafrost is frozen ground. It contains ice, and sometimes this ice is not distributed evenly under the surface. It’s very hard to predict where it’s going to be, and thus where the impact will be as the permafrost warms and thaws”.

I remember being shocked to see that people in Greenland were having to use refrigeration to keep the foundations of their buildings on permafrost stable. The scale of the problem is clearly much greater in cities like Yakutsk.

Then, of course comes the feedback problem, when thawing permafrost releases the organic carbon stored within it. Let me give the last word to Hugues Lantuit:

“This is a major issue, because it contains a lot of what we call organic carbon, and that is stored in the upper part of permafrost. And if that warms, the carbon is made available to microorganisms that convert it back to carbon dioxide and methane. And we estimate right now that there is twice as much organic carbon in permafrost as there is in the atmosphere. So you can see the scale of the potential impact of warming in the Arctic.”

Arctic residents in hot water

At the swimming club last weekend, one of my fellow swimmers complained the water was too warm. She said she couldn’t swim at her usual speed when the temperature in the pool rose even a little bit. It left her feeling tired and lethargic. So how much more dramatic must it be for the tiny creatures at home in cold Arctic waters, when a warm influx changes their surroundings and living conditions.?

The warming of Arctic waters with climate change is likely to produce radical changes in the marine habitats of the High North. Data from long-term observations in the Fram Strait, which researchers from the Alfred Wegener Institute (AWI) have now analysed and published in the journal “Ecological Indicators”, confirms that even a short-term influx of warm water into the Arctic Ocean would suffice to fundamentally impact the local symbiotic communities, from the water’s surface down to the deep seas. They found that this happened between 2005 and 2008.

The deep sea observatory

Over the past 15 years, researchers from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for polar and marine science (AWI) have been keeping an eye on the sensitive marine ecosystem in the Fram Strait, the sea lane between Greenland and Svalbard .The institute operates a deep-sea observatory there, known as “HAUSGARTEN”, which translates literally as house garden. It is actually a network of 21 individual mini research stations. Every summer, scientists pay them a visit and collect water and soil samples. Some of the stations have anchored systems that operate year-round, recording the water temperature and tides, collecting water and soil samples at regular intervals, and capturing the sediments that drift down to the seafloor from the upper water layers.

“This is the only observatory of its kind in the world. There’s no other project in which readings from the surface down to the ocean floor were taken in fixed positions over such a long time – let alone in the polar regions,” says AWI biologist Thomas Soltwedel.

For the current publication, the AWI researcher and his team analysed the first 15 years of the HAUSGARTEN dataset. The Fram Strait is especially interesting for Soltwedel and his colleagues because it represents the only deep juncture in the Arctic Ocean, allowing water masses from the Atlantic to flow into the Arctic to the west of Svalbard. In turn, water and ice floes find their way back out of the Arctic Ocean on the strait’s Greenland side.

Too warm for comfort

Until now, the scientists say it was unclear just how polar marine organisms were responding to the warming of the ocean and shrinking sea-ice cover. Now, the long-term observations show that arctic marine habitats could change radically if subjected to a sustained rise in temperature. The AWI researchers say their most surprising finding is that the thermally induced changes at the ocean surface can rapidly spread to affect life in the deep seas.

Normally the water near the surface, which flows north out of the Atlantic through the Fram Strait, has an average temperature of three degrees Celsius. With the help of their observatory, the AWI researchers were able to establish that from 2005 to 2008 the average temperature of the inflowing water was one to two degrees higher: “In that time, large quantities of warmer water poured into the Arctic Ocean. Since polar organisms have adapted to living in constant cold, this extra heat input hit them like a temperature shock,” Soltwedel explains.

He says the reactions in the ecosystem were correspondingly extreme: “We were able to identify serious changes in various symbiotic communities, from microorganisms and algae to zooplankton.”

Migrating sea creatures

One major change described in the article was the increase in free-swimming conchs and amphipods, which are normally found in the more temperate and subpolar regions of the Atlantic. In contrast, the number of conchs and amphipods in the Arctic dropped significantly.

The researchers also noted a decline in small, hard-shelled diatoms. Prior to the unexpected influx of warm water, they made up roughly 70 per cent of the vegetable plankton in the Fram Strait. But during the warm phase, the foam algae Phaeocystis took their place. A change with consequences, Soltweder explains: “Unlike diatoms, foam algae tend to clump and sink to the ocean floor, where they become a food source. But the sudden rise in available food led to major changes in deep-sea life, including a noticeable increase in the settlement density of benthic organisms.”

If you are not a marine biologist, you may be wondering what that means for the future of the Arctic and why we should be concerned about it. The problem is that all of this affects the Arctic food web.

The scientists can’t say exactly how at this point. But, as with so many other aspects of climate change: “Above all, we’re troubled by the simple fact that the changes have been so rapid, and so far-reaching.”

New residents here to stay

Since the flow of warm water has subsided, the water temperature in the Fram Strait has stabilised – though it is still slightly above the average value from before 2005. Yet some of the changes appear to be there to stay. The conchs from the lower latitudes seem to have made a home for themselves in the Fram Strait.

As usual, the scientists are reluctant to say whether the warm-water influx they monitored is due to climate change or could be part of natural climate fluctuations. They say they need data covering several decades to be more certain.

But either way, the results of the ecological long-term studies clearly show that even short-term changes in ocean temperature can drastically impact life in the Arctic. So it looks like there will certainly be more to come, as the world continues to heat up.

Feedback