Search Results for Tag: Barrow

Arctic sea ice: is the minimum maximum the new normal?

Even the winter sea ice is waning (Off Svalbard, pic. I.Quaile)

If you blinked, you might have missed it. The confirmation came this week that the Arctic sea ice reached yet another all-time low this past winter. It came and went, without too much ado.

Maybe the excitement was just past. The maximum extent was actually reached on March 7th, but of course you can only be sure it is really not going to spread any further once it has definitely been retreating for some time with the onset of spring.

I was waiting for the NSIDC confirmation, but not with any doubt in my mind that it would tell us officially the maximum for this season would be a minimum.

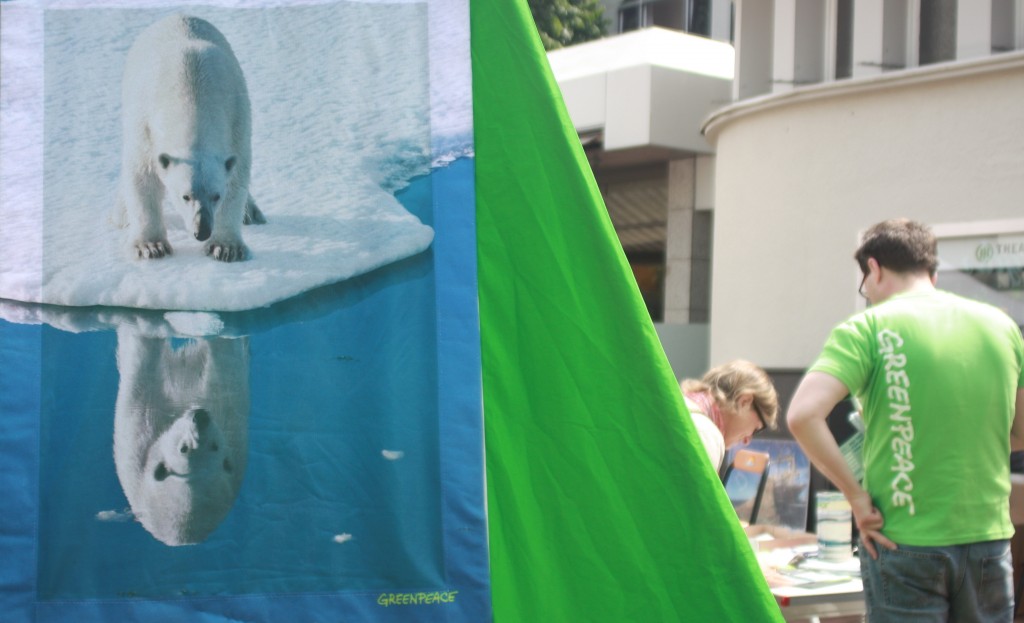

The danger is a “so what?” kind of reaction, or resignation, with the feeling that nothing short of some kind of unprecedented experimental geo-engineering could save the Arctic summer sea ice in the coming years, as the world continues to warm.

Lowest on record

The National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), part of the Cooperative Institute for Research in Environmental Sciences at the University of Colorado Boulder, and NASA confirmed this week that Arctic sea ice was at a record low maximum extent for the third straight year.

It reached the maximum on March 7, at 14.42 million square kilometers (5.57 milion square miles). Since then, it has started its annual decline with the start of the melt season. Some time in September it will reach its minimum.

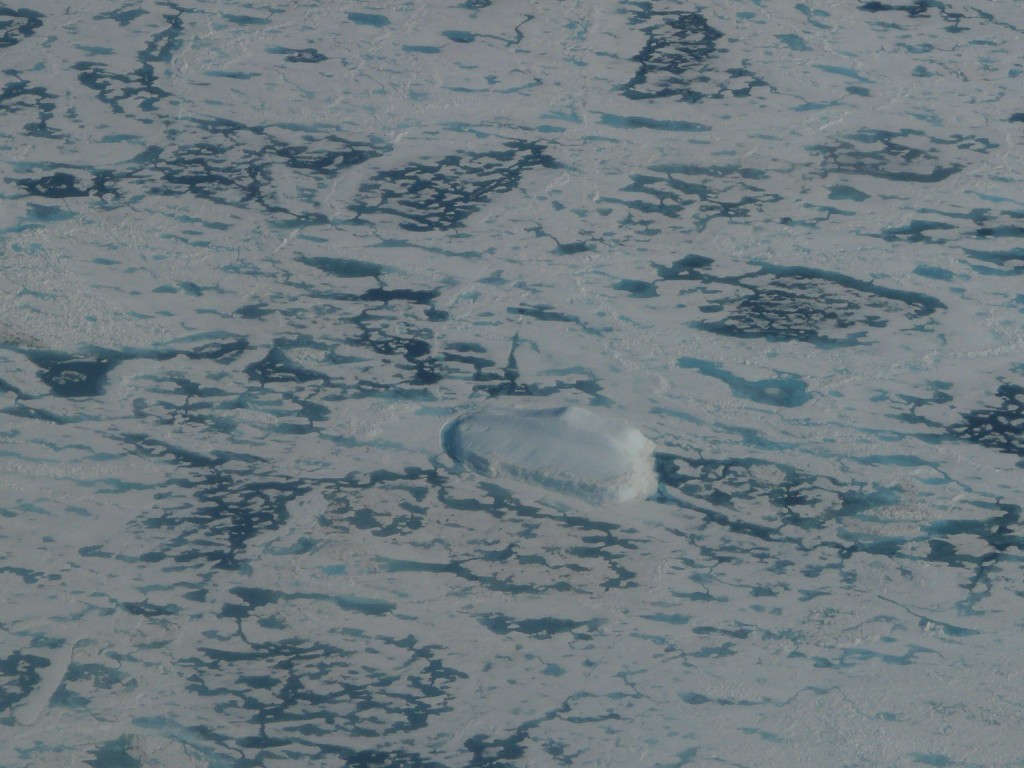

Sea ice going, going, gone? (Photo: I Quaile, off Svalbard)

This year’s maximum is the lowest in the 38-year satellite record. NSIDC scientists said a very warm autumn and winter had contributed to the record low maximum. Air temperatures were 2.5 degrees Celsius (4.5 degrees Fahrenheit) above average over the Arctic Ocean. Against the background of overall warmth came a series of “extreme winter heat waves over the Arctic Ocean, continuing the pattern also seen in the winter of 2015”, NISDC said in a statement.

The air over the Chukchi Sea northwest of Alaska and the Barents Sea north of Scandinavia was even warmer, averaging around 9 degrees Fahrenheit (five degrees C) above the norm.

NSIDC director Mark Serreze said in his statement: “I have been looking at Arctic weather patterns for 35 years and have never seen anything close to what we’ve experienced these past two winters.”

The winter ice cover was also slightly thinner than that of the past four years, according to data from the European Space Agency’s CryoSat-2 satellite. Data from the University of Washington’s Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimiliation System also showed that the ice volume was unusually low for this time of year.

Record summer melt ahead?

“Thin ice and beset by warm weather – not a good way to begin the melt season,”, said NSIDC lead scientist Ted Scambos.

A low maximum does not necessarily mean the minimum to be measured in September will also be a record low, as it depends on summer weather patterns. But Julienne Stroeve from NSIDC and professor of polar observation and modeling at the University College London said “Such thin ice going into the melt season sets us up for the possibility of record low sea ice conditions this September”.

“While the Arctic maximum is not as important as the seasonal minimum, the long-term decline is a clear indicator of climate change”, said Walt Meier, a scientist at the NASA Goddard Space Flight Center Cryospheric Sciences Laboratory and an affiliate scientist at NSIDC. Iceblog readers might wonder if that is stating the obvious, but given the attitudes of the US administration, you can’t take anything for granted.

Data from satellites is key. Reception centre at KSAT in Tromso, Norway, Pic. I Quaile)

The September sea ice measurements began to attract attention in 2005, when the ice extent first shrank to a record low over the period of satellite observations. It broke the record again in 2007 and in 2012. There used to be little interest in the maximum extent of the Arctic sea ice at the end of winter. I can remember reading with concern and writing a piece about the maximum extent also reaching a record low in 2015.

NOAA (climate.gov, “science & information for a climate-smart nation”!) said in its statement:

“Arctic sea ice extents have followed a steady downward trajectory since the start of the 21st century – at the same time global temperatures have reached new record highs. Betides setting multiple record low summertime minimum extents, Arctic sea ice began to exhibit a pattern of poor winter recovery starting around 2004.”

Living on thin ice

I remember an expedition to Alaska in 2008, when locals at Barrow told me about their personal experiences of the sea ice becoming thinner and less dependable. Some years later I heard similar reports from people in Greenland, who were selling their sled dogs and buying boats in preparation for changing from ice to open water fishing. The data backs them up.

Sled dog – out of work? (I.Quaile, Greenland)

Yereth Rosen, writing for Alaska Dispatch News, draws attention to the problems of continuing to collect that data. She quotes NSIDC’s Serreze:

“Just how well the center will be able to track sea ice in the future remains unclear. No new satellite is expected to be in place until 2020, and there are concerns about potential interruptions in the record that goes back to 1979… We’re at a situation where the remaining passive microwave instruments up there are kind of elderly. If we have satellite failures, we could lose that eye in the sky”.

Now there is a worrying thought.

Against the background of budget cuts proposed by the Trump administration, that – to put it mildly – does not regard tracking climate change as a high priority – scientists are understandably worried about the future of scientific research on climate and environment related issues.

Method in the madness?

Without reliable continuous satellite data, it would be much harder to track how climate change is affecting the polar regions, the ocean and our planet in general. This may well be the intention of climate-change deniers behind the scenes. But climate change itself will not go away – and the impacts will be increasingly evident.

Tim Ellis, writing for Alaska Public media, quotes Serreze as saying the polar ice cap will not last long if the region continues to warm at this rate.

“We are on course sometime in the next few decades, maybe even earlier, to have summers in the Arctic where, you go up there at the end of August, say, and there’s no ice at all.”

“The view from space in the fall of around 2040” , he went on – assuming we still have satellites to take the pictures – “will be of a blue Arctic Ocean, aside from some scattered icebergs and clusters of pack ice”.

I don’t know about you, but I find that a rather depressing thought.

My kind of sea ice – frozen Chukchi Sea (Pic: I.Quaile)

Implications for the rest of the globe

Andrea Thompson, for Climate Central, writes “even in the context of the decades of greenhouse gas-driven warming, and subsequent ice loss in the Arctic, this winter’s weather stood out.”

She also reminds us of the global impacts of a warming Arctic and decline in sea ice:

“The Arctic was one of the clear global hotspots that helped drive global temperatures to the second- hottest February on record and the third-hottest January, despite the demise of a global heat-boosting El Nino last summer.”

This week the UN’s World Meteorological Organisation (WMO) said 2016 had been the hottest year ever recorded, and that the record-breaking heat had continued into 2017, sending the world into “truly uncharted territory”.

“The dramatic melting of Arctic ice is already driving extreme weather that affects hundreds of millions of people across North America, Europe and Asia, according to emerging research”, Damian Carrington writes in the Guardian.

On March 15th, Carrington published an article entitled “Airpocalypse smog events linked to global warming”, referring to extreme smog occurrences in China.

Optimism – the only way to go?

This week I interviewed German oceanologist and climatologist Mojib Latif. I wanted to find out whether the highly unusual extreme rainfall and flooding happening in Peru could be explained by natural cycles or was likely to be a climate change impact which could reoccur. You can read the interview here or listen to it on my Living Planet show this week online or on soundcloud.

Professor Latif on a visit to Bonn. (Pic. I.Quaile)

The professor stressed that the scientists are baffled, because it is not really the time for an el Nino, although this seems to be a “coastal el Nino”, driven by exceptionally warm water off the coast. Of course he is reluctant to attribute any single event to climate change. He stated unequivocally, though, that the warming of the ocean worldwide was absolutely inexplicable without anthropogenic CO2 emissions, that this is all in line with climate models and that we should all be preparing for an increasing number of increasingly extreme weather events, as the world warms.

He says the governments of the world (apart perhaps from the new US administration) are in no doubt that climate change is happening and they need to halt it. But they have so far failed in their attempts.

When I asked Professor Latif if he still felt optimistic, he told me we really had no other choice. While critical of the lack of government action, he is convinced the world will realize that renewables are ultimately far superior to fossil fuels and will ultimately prevail. The question is whether that will happen in time. As far as the Arctic summer sea ice is concerned, I have to go with a Scots expression: “A hae ma doots”.

Unbaking Alaska?

When I first went to Alaska in 2008, “Unbaking Alaska“ was the title of the reporting project on how climate change is affecting the region and what the world might be able to do about it. I had to explain the title to my German colleagues, unfamiliar with the “Baked Alaska” dessert, while my North American and British colleagues thought it was a quirky, witty little title.

This week, when I saw an article in the Washington Post entitled “As the Arctic roasts, Alaska bakes in one of its warmest winters ever”, I found the “dessert” had become a little stale .

The thing about “Baked Alaska” is that the ice cream stays cold inside its insulating layer of meringue. Unfortunately, all the information coming out of Alaska and the Arctic in general at the moment, suggest that the ice is definitely not staying frozen.

Too hot for comfort?

In the Washington Post article, Jason Samenow refers to this winter’s “shocking warmth” in the Arctic, some seven degrees above average. Alaska’s temperature, he says, has averaged about 10 degrees above normal, ranking third warmest in records that date back to 1925. Anchorage has found itself with a lack of snow.

“This year’s strong El Nino event, and the associated warmth of the Pacific ocean, is likely partly to blame, along with the cyclical Pacific Decadal Oscillation – which is in its warm phase”, Samenow writes. Lurking in the background is that CO2 we have been pumping out into the atmosphere over the last 100 years or so.

Sea ice on the wane?

Meanwhile, the Arctic sea ice is at a record low. Normally, in the Arctic, the ocean water keeps freezing through the entire winter, creating ice that reaches its maximum extent just before the melt starts in the spring. Not this time.

Yereth Rosen wrote on ADN on Feb. 24th the sea ice had stopped growing for two weeks as of Tuesday. He quotes the NSIDC as saying the ice hit a winter maximum on February 9th and has stalled since.

“If there is no more growth, the Feb. 9 total extent would be a double record that would mean an unprecedented head start on the annual melt season that runs until fall”.

This would be the earliest and the lowest maximum ever. Normally, the ice extent reaches its maximum in early or mid-March.

The most notable lack of winter ice has been near Svalbard, one of my own favourite, icy places.

The experts say it’s too early to say whether this is “it” for this season. There is probably more winter to come. But even if more ice is able to form, it will be very thin.

Toast or sorbet?

Coming back to those culinary clichés: Samenow in the Washington post writes of the second “straight toasty winter” in the “Last Frontier”. The links below his online article are listed under “more baked Alaska”. Amongst them I find the headline: “As Alaska burns, Anchorage sets new records for heat and lack of snow” and “Record heat roasts parts of Alaska”.

The trouble comes when these catchy titles become clichés and somehow stop being quirky.

Don’t we run the risk of not doing justice to the serious threat climate change is posing to the most fragile regions of our planet? Sometimes I worry that the warming of the Arctic is becoming something people take for granted, and, even more dangerous, something we can’t do much about. At times I sense a cynicism creeping in.

I for one will be keeping my oven-baked cake and chilled ice cream separate this weekend.

Is it possible to un-bake Alaska? Food for thought.

Picture gallery on “Baked Alaska” expedition.

Record permafrost erosion in Alaska bodes ill for Arctic infrastructure

At Point Barrow, the northernmost point in the USA, a whole village was lost to erosion (Pic: I.Quaile)

Sitting in my office on the banks of the river Rhine, I am trying to imagine what would happen if the fast-flowing river was eating into the river bank at an average rate of 19 metres per year. It would not belong before our broadcasting headquarters, the UN campus tower and the multi-story Posttower building collapsed, with devastating consequences.

Fortunately, Bonn is not built on permafrost, so we don’t have that particular concern.

Record erosion on riverbank

The record erosion German scientists have been measuring in Alaska probably hasn’t been making the headlines because it is happening in a very sparsely populated area, where no homes or important structures are endangered.

Nevertheless, it certainly provides plenty of food for thought, says permafrost scientist Jens Strauss from the Potsdam-based research unit of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI). He and an international team have measured riverbank, erosion rates which exceed all previous records along the Itkillik River in northern Alaska. In a study published in the journal Geomorphology, the researchers report that the river is eating into the bank at 19 metres per year in a stretch of land where the ground contains a particularly large quantity of ice.

“These results demonstrate that permafrost thawing is not exclusively a slow process, but that its consequences can be felt immediately”, says Strauss.

With colleagues from the USA, Canada and Russia, he investigated the river at a point where it cuts through a plateau, where the sub-surface consists to 80 percent of pure ice and to 20 percent of frozen sediment. In the past, the ground ice, which is between 13,000 and 50,000 years old, stabilized the riverbank zone. The scientists, who have been observing the location for several years, demonstrated that the stabilization mechanisms fail if two factors coincide. That happens when the river carries flowing water over an extended period, and where the riverbank consists of steep cliff, which has a front facing south, and is thus exposed to a lot of direct sunlight.

Minus 12C average no safeguard

The warmer water thaws the permafrost and transports the falling material away, and in spite of a mean annual temperature of minus twelve degrees Celsius, summer sunlight makes it warm enough to send lumps of ice and mud flowing down the slope, according to Michail Kanevskixy from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, lead author of the study.

Overall, between 2007 and 2011, the cliff – which is 700 metres long and 35 metres high – retreated up to 100 metres, resulting in the loss of 31,000 square metres of land area. That is a large area, around 4.3 football fields, the scientists calculate.

In August 2007, they also witnessed how fissures formed within a few days, up to 100 metres long and 13 metres deep.

“Such failures follow a defined pattern”, says Jens Strauss. “First, the river begins to thaw the cliff and scours an overhang at the base. From here, fissures form in the soil following the large ice columns. The block then disconnects from the cliff, piece by piece, and collapses”.

Infrastructure under threat

Although these spectacular events happened far from populated areas and infrastructure, the magnitude of the erosion gives cause for much concern, given the rate at which temperatures are increasing in the Arctic. The scientists want their information to be used in the planning of new settlements, power routes and transport links. They also stress that the erosion impairs water quality on the rivers, which are often used for drinking water.

But what about those areas of the High North where there are settlements and key infrastructure? Russia is starting to get very worried about the effects of increasing permafrost erosion.

Last month the country’s Minister of Natural Resources, Sergey Donsjkoy, expressed grave concern. The Independent Barents Observer quoted the Minister as saying, in an interview with RIA Novosti, he feared the thawing permafrost would undermine the stability of Arctic infrastructure and increase the likelihood of dangerous phenomena like sinkholes. Russia has important oil and gas installations in Arctic regions. Clearly, any damage would have considerable economic implications. There are also whole cities built on permafrost in the Russian north.

System to cool the foundations of a building on permafrost in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland (pic: I.Quaile)

High time to adapt

In 2014, I interviewed Hugues Lantuit, a coastal permafrost geomorphologist with the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, about an integrated database on permafrost temperature being set up as an EU project. He told me it would be very hard to halt this permafrost thaw, and stressed that permafrost underlies 44 percent of the land part of the northern hemisphere.

“The air temperature is warming in the Arctic, and we need to build and adapt infrastructure to these changing conditions. It’s very hard, because permafrost is frozen ground. It contains ice, and sometimes this ice is not distributed evenly under the surface. It’s very hard to predict where it’s going to be, and thus where the impact will be as the permafrost warms and thaws”.

I remember being shocked to see that people in Greenland were having to use refrigeration to keep the foundations of their buildings on permafrost stable. The scale of the problem is clearly much greater in cities like Yakutsk.

Then, of course comes the feedback problem, when thawing permafrost releases the organic carbon stored within it. Let me give the last word to Hugues Lantuit:

“This is a major issue, because it contains a lot of what we call organic carbon, and that is stored in the upper part of permafrost. And if that warms, the carbon is made available to microorganisms that convert it back to carbon dioxide and methane. And we estimate right now that there is twice as much organic carbon in permafrost as there is in the atmosphere. So you can see the scale of the potential impact of warming in the Arctic.”

Paris: A COP-out for Arctic Peoples?

As I write, the climate negotiations have been extended into Saturday. Same procedure as every year? While I still hope the seemingly never-ending bickering will result in a document which will at least signal the end of the fossil fuels era, I cannot help feeling a sense of sadness and regret, that this is all way too late for the Arctic, as I discussed in the last blog post. And I wonder how all this feels to indigenous folk living in the High North, as they see their traditional lifestyles melting away.

On a recent edition of DW’s Living Planet programme, Lakeidra Chavis reported on the effect of melting permafrost on indigenous communities in Alaska. Chatting to a colleague in between times about the story, she told me how moved she was to hear how skulls had been washed up in a river as the permafrost at a burial site thawed.

Climate change impacts the present, future – and past

I had a kind of déjà vu feeling. Back in 2008, in those early days of the Ice Blog, I travelled out to Point Barrow, the northernmost point in the USA, with archaeologist Anne Jensen. We visited the site where a village had had to be re-located because of coastal erosion, with melting permafrost and dwinding sea ice. She told me how she was called up by distraught locals in the middle of the night and asked to help recover the remains of their ancestors before they were washed into the ocean. My colleague here in Bonn was surprised to hear that I had conducted that interview back in 2008. How could this have been known at that time already, yet so little publicized?

Climate change impacts: Jensen at the site of a lost Inupiat village at Point Barrow, 2008 (Pic.: I.Quaile)

Victims or culprits?

While a lot of attention is focused (and rightly so) on the impacts on developing countries, Asia, Africa, rising sea levels, this is an issue a lot of people know very little about. In an article for Cryopolitics Mia Bennet puts her finger on an interesting aspect of all this. The Arctic indigenous peoples are living in industrialized, developed states. That gives them an interesting status, somewhere between being victims and perpetrators of climate warming.

“A discourse of victimization pervades much Western reporting on the Arctic”, she writes. A lot of people in the region tend to blame countries outside the region for climate change. She quotes a study in Nature Climate Change in which researchers found that emissions from Asian countries are the largest single contributor to Arctic warming. But she notes that gas flaring emissions in Russia and forest fires and gas flaring emissions in the Nordic countries are the second two biggest contributors. And these industries are often supported by locals, not least because of the jobs and prosperity they bring.

This brings me back to some encounters I had during that trip to Alaska in 2008 – and others since, with Inuit people employed in the oil sector. They were reluctant to accept that the industries that provided their livelihoods could ultimately be literally eroding the basis of their cultures. Russia, the USA, Canada, Norway – are all countries involved in oil and gas exploitation. Some northern regions are highly dependent on the industries which are warming the climate.

“And for their part, Arctic countries must realize that reducing emissions begins at home on the region’s heavily polluting oil platforms and gas flaring stacks – not in Paris”, says Mia Bennet.

All up to Paris?

The sad truth is that even the two-degree target – or the 1.5 currently being debated – will not have much of an impact on Arctic warming.

Mia Bennet puts it bluntly. “Regardless of whether a positive or negative outcome is reached in Paris at COP 21, it will not dramatically affect the Arctic.”

A delegation of indigenous leaders from the Arctic countries is in Paris at the talks. Both the Inuit Circumpolar Council and the Saami Council have sent delegates, with the aim of highlighting the consequences of a warming climate for the polar regions.

Council representatives are from three distinct Inuit regions: Canada, the USA and Greenland. The Chukotka region of Russia also has a substantial Inuit population, who are not directly represented in Paris, but belong to the Council. The Saami Council has representatives from Finland, Russia, Norway and Sweden. Both sets of delegates are attending as observers, without voting rights.

In a position paper, Inuit Circumpolar Council Chair Okalik Eegeesiak of Canada stresses the Inuit’s deep concern about the impacts of climate change on their cultural, social and economic health.

She describes the Arctic’s sensitive ecosystem as a “canary in the coal mine for global change”. Following that metaphor, the canary must be close to suffocating.

The Inuit representatives in Paris are appealing for stronger measures to keep global temperature rise below 1.5 degrees C. They stress that the land and sea sustain their culture and wildlife, “on which we depend for food security, daily nutrition and overall cultural integrity”.

But ultimately, in a world where altruism seldom plays a part, it may be their other argument – the role of the Arctic in influencing the global climate system – that convinces negotiators of the need to work against global warming. With increasing knowledge and awareness of the extent to which the Arctic influences global processes and thus weather and climate all over the globe, the willingness to take measures to prevent further deterioration of the cryosphere is likely to increase. Whether it will be in time is another question. Any negotiator in Paris who has taken a brief moment off to read this – remember, we are not talking about a remote region with a small population. We are all in this together.

Farewell to ‘Last Ice’ victims in a rapidly warming world

Ice Blog readers may remember the story of the two ice researchers and polar explorers who died when they broke through unexpectedly thin ice in the Canadian Arctic earlier this year. This week I had the chance to join friends and admirers of Marc Cornelissen and Philip de Roo at a ceremony held in their home country, the Netherlands. The unusually warm November weather, with people sitting out eating ice cream, seemed oddly apt for a tribute to two people who died doing climate research.

![]() read more

read more

Feedback