Search Results for Tag: CO2

Greenland earthquake and tsunami – hazards of melting ice?

Is gradual CO2 increase speeding up Greenland ice sheet melt? (Pic: I.Quaile)

Following the news over the weekend with a trip to Greenland this summer at the back of my mind, my attention was immediately caught by reports of a tsunami and earthquake in Greenland. Four people were reported missing. Buildings had been swept away, including the power station on the island of Nuugaatsiaq. Greenland is not the first place that comes to mind in connection with earthquakes and tsunamis. But in fact they are not as rare as you might think.

The cause of the weekend’s event is still unclear. But a tweet from the Greenland Climate Research Centre links to an article in the Washington Post from June 25 2015:

“Glacial earthquakes”

The article reports on a paper published in the journal Science at that time by researchers from Swansea University in the UK, the Lamont-Doherty Earth Observatory at Columbia University and several other institutions. It says the loss of Greenland’s ice can generate “glacial earthquakes”.

“When vast icebergs break off at the end of tidal glaciers, they tumble in the water and jam the glaciers themselves backwards. The result is a seismic event detectable across the Earth”.

Worrying reading indeed, as GCRC wrote in their tweet.

The Washington Post article quoted Meredith Nettles from Columbia, one of the co-authors.

She specifically mentions the tsunami effect:

“The tsunami is caused because the iceberg has to move a lot of water out of the way as it tips over”.

Arctic icebergs can displace a lot of water (Pic: I.Quaile, Greenland)

Too early to say

I have been trying to find more information on what the experts think caused this weekend’s particular event. So far, there is no clarity. But the GCRC tweet with link to the Washington Post article seems to indicate they think it could be ice-related.

Another theory is that the quake and tsunami were caused by a landslide. The news agency DPA says the Geological Survey of Denmark and Greenland are still trying to determine the cause of the tsunami.

“Initially, geologists believed it was triggered by an earthquake, but another theory blamed a large landslide from one of the mountains on the fjord system”.

It seems the Danish Arctic Commando published images showing signs of an extensive landslide.

“Tsunamis and large waves at times affect Greenland’s coasts, but, according to the Geological Survey, they are usually caused by landslides and the breaking off of ice from melting glaciers”, the agency writes.

DPA earlier noted that the Danish earthquake authority GEUS had recorded a 4.0 quake.

Warning from Greenland ice cores

One way or other, the weekend tsunami is unlikely to allay anxiety about the effects of rapidly melting substantial quantities of ice.

And a study just published by Germany’s Alfred-Wegener-Institute (AWI) provides more food for thought about human-induced changes to our climate. It indicates that the gradual nature of the changes we are making to the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is no guarantee that the resulting climate change will also be gradual. On the contrary. Computer models based on information from ice cores from Greenland show that in high latitudes of the northern hemisphere, there were abrupt changes in climate, which the scientists attribute to a gradual increase in CO2.

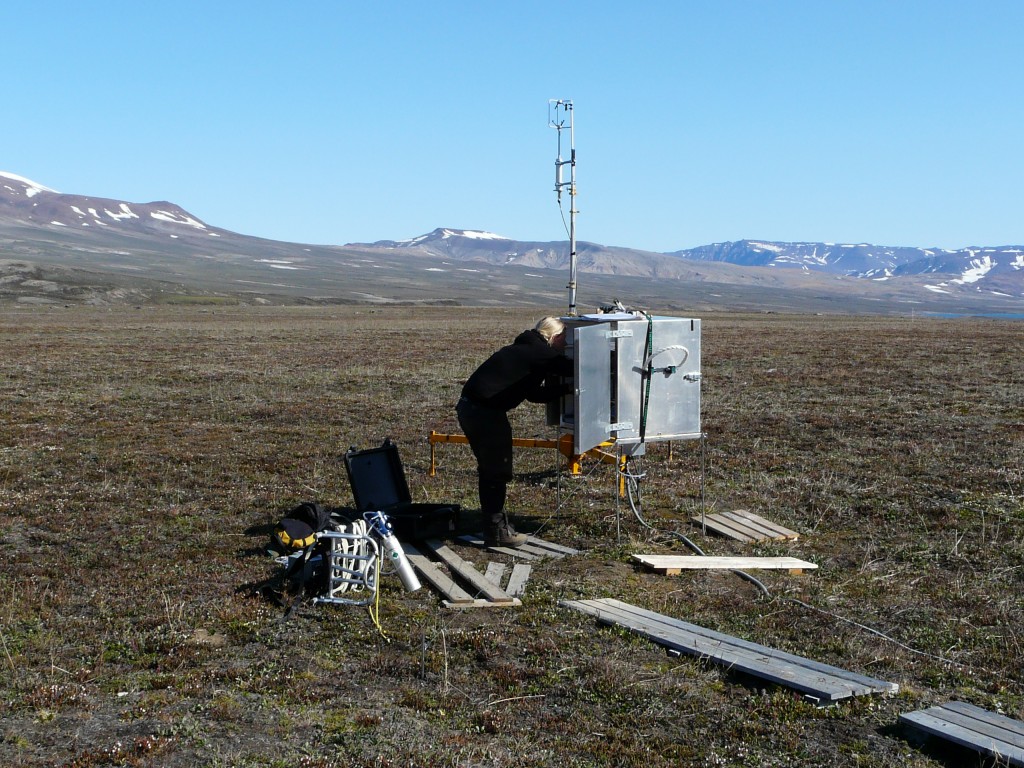

Rising CO2 emissions – no part of the world is spared (Measuring station on Svalbard, Pic. Quaile)

During the last ice age, they say that the influence of atmospheric CO2 on the North Atlantic Current within a few decades led to an increase in temperature of up to 10 degrees Celsius in Greenland. The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, by scientists from AWI and the University of Cardiff shows that in recent earth history, there have been situations when gradual increases in CO2 concentrations at what are known as “tipping points” led to abrupt changes in ocean circulation and climate.

Sudden warm age on the horizon?

Lead author Xu Zhang says the study is the first to prove that a gradual increase in CO2 can set off very rapid warming, based on interactions between ocean currents and the atmosphere.

The authors also show that the rise in CO2 is the main cause of chances in ocean currents during the transition from an ice age to a warm period.

Of course, they add, the framework conditions today are different from those during an ice age, so it is not possible to say the rise in CO2 will have similar effects in future.

But they say they can definitely show that there were abrupt climate changes in Earth’s history, which can be traced back to continual rises in CO2 concentrations.

Reason enough for concern to people living on the coast of Greenland – not to mention the rest of us, given the key role the world’s biggest island, with the biggest freshwater mass in the northern hemisphere sitting on top of it in the form a giant ice sheet, plays in influencing climate and sea levels around the globe?

Trump’s alternative reality? No warming, cool oceans, intact coral

Melting or not? (I.Quaile, Greenland)

“Irene, have you heard the news? Looks like Trump has pulled out of the Paris Agreement.” While the US President kept the suspense up until Thursday night – has he, hasn’t he, will he, won’t he -I struggled to reconcile his action with what I was hearing from a wide spectrum of highly intelligent people with decades of research and experience to their credit.

I was in Kiel this week, on Germany’s Baltic coast, attending a working meeting of the scientists involved in BIOACID, a national German programme (supported by the BMBF, Federal Ministry of Education and Research) to investigate the “Biological Impacts of Ocean Acidification”. It has almost run its course, eight years of research in the bag.

And what I was hearing did nothing to allay my concern about the impacts of our greenhouse gas emissions. We are rapidly and undeniably changing the planet we live on – land and sea. And that applies particularly to the Arctic.

GEOMAR’s research vessel Alkor in Kiel getting ready for her next trip (Pic:.I.Quaile)

The scientific evidence

Can President Trump really fail to see the dangers of our human interference? Is he really oblivious to what climate change is doing to the ocean that covers 70 percent of the surface of our planet?

Maybe he lives in a parallel universe, where alternative facts prevail.

Back in 2010, I was able to witness the work of some of the scientists assembled in Kiel this week at first hand, as they lowered mesocosms, a kind of giant test tubes, into the Arctic Ocean off the coast of Svalbard. The aim was to find out how the life forms in the water would react to increasing acidification of their environment, as our greenhouse gas emissions result in more and more CO2 being absorbed into the ocean.

Drawing the threads together

Ulf Riebesell with team members deploying experiments at Svalbard (Pic.I.Quaile)

Ulf Riebesell is Professor of Professor of Biological Oceanography at, GEOMAR, the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, and the coordinator of BIOACID.

When I first met him, he was kitted out in survival gear, supervising the transport and deployment of the mesocosms from Germany up to the Svalbard archipelago. He doesn’t need the cold-weather gear this week, in a summery Kiel, where he gathered representatives of the different working groups involved in the German project to draw some threads together as the project approaches its conclusion in November.

Good timing. The results will be ready to hand to the delegates attending this year’s UN climate extravaganza, COP23, in Bonn. Another key piece in the jigsaw puzzle of how climate change is affecting the world we live in and will determine the future of coming generations.

All creatures great and small

The scientists assembled represent a wide range of expertise. From the tiniest of microbes through algae, corals, fish and the myriad organisms that live in our seas- they have been trying to find out what happens when living conditions change for our fellow planetary residents – and how all this affects an ever-increasing population of humans and the complex societies we live in.

The ocean is changing at an unprecedented rate. It is becoming warmer, even in the depths, and it is becoming more acidic.

The work of Riebesell and his colleagues has shown that in our rapidly warming world, the CO2 that goes into the ocean is reducing the amount of calcium carbonate in the sea water, making life very difficult for sea creatures that use it to form their skeletons or shells. This will affect coral, mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish as well as fish and other organisms. Some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future.

Cold water coral in the GEOMAR lab in Kiel. (Pic.I.Quaile, thanks to Janina Büscher)

The Arctic predicament

Acidification is not something that affects all regions and species equally. Once again, the Arctic is getting the worst of it. Cold water absorbs CO2 faster. Experiments in the Arctic indicate that the sea water there could become corrosive within a few decades, as Ulf Riebesell has told me on several occasions since I first met him on Svalbard in 2010. “That means the shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve.”

Scientists warn that a combination of acidification, warming and stressors like pollution of all sorts will ultimately affect the food chain. (Indeed that is already happening).

Warming as usual?

While the BIOACID project comes to an end and the scientists fight for new funding to carry on research into ocean acidification, which requires a combination of field-work and modelling, the world continues on course for far more than the two degrees – or 1,5 set out in the Paris Agreement.

“Ocean Warning” was the cover title on the Economist magazine this week, ahead of next week’s UN Oceans Conference in New York.

“The Paris Agreement is the single best hope for protecting the ocean and its resources”, the magazine reads. But it stresses: “the limits agreed on in Paris will not prevent sea levels from rising and corals from bleaching. Indeed, unless they are drastically strengthened, both problems risk getting much worse. Mankind is increasingly able to see the damage it is doing to the ocean. Whether it can stop it is another question”.

Seaweed and algae in experimental tanks at GEOMAR, Kiel (Pic.I.Quaile)

Bending the truth?

At the meeting in Kiel, I asked Professor Hans-Otto Pörtner, the other coordinator of BIOACID, senior scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute and co-chair of the IPCC Working Group 2 for his view of the current situation, with US President Trump getting set to leave the Paris Agreement:

“Climate change is clearly human made, responsible leadership means that this cannot simply be denied or ignored. I think this is a call for better education and information of the public so that it cannot be misled by bending the truth – and this is what it comes down to. As the last report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) put it: “Without additional mitigation efforts beyond those in place today, and even with adaptation, warming by the end of the 21st century will lead to very high risk of severe, widespread and irreversible impacts”. In its previous analysis of decision-making to limit climate change and its effects, the IPCC also noted that climate change is a problem of the commons, requiring collective action at the global scale. Effective mitigation will not be achieved if individual agents advance their own interests independently.”

Call to action

Indeed. We are all in this together.

But there is not only bad news:

“It remains to be seen to what extent U.S. emissions will be driven by federal policy, or actions at the State and city level, or by market and technological changes”, Professor Pörtner told me.

There is, it seems to me, an upside to President Trump’s decision to live in his own alternative reality. It galvanizes those of us who live in the real world to make sure climate action goes ahead. China and the EU closed ranks this week. States, companies, civil societies and committed individuals across the USA are stressing they will press on with the green energy revolution regardless.

In the interests of the icy north – and the rest of the planet it influences so considerably – we really have no choice.

The mesocosms are used to research the effects of acidification on ocean-dwellers. (I.Quaile, Svalbard)

LISTEN:

Living Planet: STAND UP FOR THE PLANET

Living Planet: UN TALKS IN TRUMP’S SHADOW

READ:

LEAVING PARIS AGREEMENT A BREACH OF HUMAN RIGHTS?

Cheap oil from the Arctic? Fake news, says climate economist Kemfert

Nothing fake about melting ice. Eiders, off Svalbard (I.Quaile).

This week I came across an interesting publication about to come on to the German market.

“The fossil empire strikes back” (Das fossile Imperium schlägt zurück) is the translation of the catchy title of a new book in German by Professor Claudia Kemfert, head of the department of energy, transportation and environment at the German Institute for Economic Research in Berlin (DIW Berlin,) and professor of energy and sustainability at the Hertie School of Governance, in Berlin.

She has also acted as advisor to the German government, the European Commission and is on the steering committee of the renowned Club of Rome.

A fossil fuels revival: happening now, or alternative facts?

I called her up to record an interview for our Living Planet radio show to find out what was behind the headline, and the sub-title: “why we have to defend the “Energiewende” (energy transition) now.

Prof Kemfert believes the fossil fuels sector is really working hard at making a comeback. That, she says, is not fake news, but the fossils lobby makes use of the latter in its attempt to turn the clock back in terms of energy production.

Kemfert argues for renewables. Copyright: Neuberg, Sebastian Wiegand

While the global transition towards renewable energy has been successful in recent years, with the costs of alternative energies reduced, the Paris Agreement signed and ratified, now, she says, the fossil fuels sector is striking back.

She says they do it by spreading fake news, creating myths about restrictions on cars, speed limits, blackouts, globally, but especially in the USA under the Trump administration. So, she argues, we have to defend the energy transformation. The window of opportunity for climate action is still open, but we are losing time.

The power of fake news

Kemfert’s aim is to debunk the myths, which she is convinced are being used to give renewable energy a bad image. Some of the examples she cited to me are false claims that renewables are more expensive, or that reliance on alternative energies will mean blackouts.

“This has never happened in Germany”, she notes, the country that gave the “Energiewende” its name and pressed ahead with the transition to renewables in recent years.

So how can fake news of this kind make such an impact that Kemfert and other like-minded experts are worried about an oil and coal revival?

“If you repeat this all the time, and repeat it on social media, people think it’s true”, she told me.

“The danger is that they can be successful”.

“The global energy transition is in danger”, she is convinced. “We are losing time to bring greenhouse gases down and help the planet to survive.

“The lobby of the fossil empire is extremely strong… the whole campaign with myths and fake news is really successful, because a lot of people believe what they say”.

So are the fossil fuel lobbyists just better at getting a message across than the other side? There could be something to that, Kemfert agreed. She says the “green lobby” is not aggressive enough. People think “we are the good ones, the energy transition comes by itself”- this is not true. Now it’s time to fight for it”.

We still have a window of opportunity, says Kemfert (Pic. I.Quaile, Alaska)

Time to march?

She calls on all scientists and people who want to protect free and democratic science, to take part in the Marches for Science, planned to take place round the globe on April 22nd.

Of course I wanted to know how she thought the global counter-attack by the “fossil empire” would impact the Arctic.

Yes, she said, this push for a fossil fuels revival could provide additional motivation to those who would like to push ahead with Arctic drilling, as climate change makes for easier and less expensive access:

“There are some aggressive industries, especially coming from the oil and gas sector, who have interest to drill for oil in the Arctic region.

For them, she says, easier access thanks to climate change would be “a nice, so-to-say side effect”.

But for the planet as a whole, climate change is so dangerous that any potential short-time business benefits are just not worth thinking about, says Claudia Kemfert:

“As a climate economist, I cannot say this (oil from the Arctic) makes economic sense, because the costs of climate change are much higher than lower costs, for example, for drilling oil in the Arctic. The costs of global climate change are so high that it cannot outweigh the cost reduction of oil drilling in the Arctic when there’s low ice. We have to move away from oil and gas, this is why it’s more economically efficient to go for an energy transition instead of drilling in areas where we have climate impacts, we are causing environmental difficulties and where we know that burning these fossil fuels will create climate change. That’s really the wrong way to go”.

Kemfert’s book is only being published in German at the moment, but there is more info on her home page, and a longer version of the English interview I conducted with her will be coming up soon on Living Planet and on the DW website.

Olympics over, but Arctic ice still chasing records

The Rio games have come to an end. Summer is drawing to a close here in Germany. It feels more like autumn today, cool with heavy rainshowers. But there’s a heatwave around the corner after what most people agree has been a very strange summer.

July followed in the record-breaking trend of the earlier months of the year, being the hottest month ever recorded on the planet.

![]() read more

read more

Arctic future: not so permafrost

“A glance into the future of the Arctic” was the title of a press release I received from the Alfred Wegener Institute this week, relating to the permafrost landscape.

“Thawing ice wedges substantially change the permafrost landscape” was the sub-title.

“I felt the earth move under my feet…” was the song line that came to my mind.

The study was led by Anna Liljedahl of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. And Fairbanks is, indeed, where I would like to have been this past week, with Arctic Science Summit Week taking place.

Arctic Council in Fairbanks

Clearly the Arctic Council thought the same and actually managed to put their wish into practice by holding a meeting of the Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs) there from March 15th to 17th. The agenda focused to a large extent, it seems, on climate change, and “placing the Council’s overall work on climate change in the context of the COP21 climate agreement” reached in Paris in December, according to a media release.

“The Council needs to consider how it can continue to evolve to meet the new challenges of the Arctic, particularly in light of the Paris Agreement on climate change. We took some steps in that direction this week”, said Ambassador David Balton, Chair of the SAOs.

Now what exactly does that mean? The Working Groups reported “progress on specific elements”. They include the release of a new report on the Arctic freshwater system in a changing climate, “cross-cutting efforts aimed at preventing the introduction of invasive alien species”, strengthening the region’s search and rescue capacity, efforts to support a pan-Arctic network of marine protected areas and promoting “community-based Arctic leadership on renewable energy microgrids”. I suppose those could be part of the process. Clearly there are a lot of interesting things going on.

NOAA’S latest – not so cheery

Against the background of NOAA’s latest revelations on global temperature development, though, they may have to speed up the pace. The combined average temperature over global land and ocean surfaces for February 2016 was the highest for February in the 137-year period of record, NOAA reports, at 1.21°C (2.18°F) above the 20th century average of 12.1°C (53.9°F). This was not only the highest for February in the 1880–2016 record—surpassing the previous record set in 2015 by 0.33°C / 0.59°F—but it surpassed the all-time monthly record set just two months ago in December 2015 by 0.09°C (0.16°F).

Overall, the six highest monthly temperature departures in the record have all occurred in the past six months. February 2016 also marks the 10th consecutive month a monthly global temperature record has been broken. The average global temperature across land surfaces was 2.31°C (4.16°F) above the 20th century average of 3.2°C (37.8°F), the highest February temperature on record, surpassing the previous records set in 1998 and 2015 by 0.63°C (1.13°F) and surpassing the all-time single-month record set in March 2008 by 0.43°C (0.77°).

Here in Germany, the temperature was 3.0°C (5.4°F) above the 1961–1990 average for February. NOAA attributes it to a large extent to strong west and southwest winds. Now that is a big difference, and I can certainly see it in nature all around. But the difference was more than double that in Alaska. Alaska reported its warmest February in its 92-year period of record, at 6.9°C (12.4°F) higher than the 20th century average.

Why worry about wedges?

So, back to Fairbanks, or at least to the changing permafrost in this rapidly warming climate, which was on the agenda there at the Arctic Science Summit Week. (See webcast.)

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, conducted by an international team in cooperation with the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (no wonder we prefer to call them AWI), indicates that ice wedges in permafrost throughout the Arctic are thawing at a rapid pace. The first thought that springs to my mind is collapsing buildings, remembering seeing cooling systems in Greenland to keep the foundations of buildings in the permafrost frozen and so stable. Of course that only affects areas which are built upon (certainly bad enough). The new study looks at what the melting ice wedges will mean for the hydrology of the Arctic tundra. And that impact will be massive, the scientists say.

The ice wedges go down as far as 40 metres into the ground and have formed over hundreds or even thousands of years, through freezing and melting processes. Now the researchers have found that even very brief periods of above-average temperatures can cause rapid changes to ice wedges in the permafrost near the surface. In nine out of the ten areas studied, they found that ice wedges thawed near the surface, and that the ground subsided as a result. So, once more, humankind is changing what nature created over thousands of years in a very short space of time. I am reminded of a recent study indicating that our greenhouse gas emissions have even postponed the next ice age.

A dry future for the Arctic?

“The subsiding of the ground changes the ground’s water flow pattern and thus the entire water balance”, says Julia Boike from AWI, who was involved in the study. “In particular, runoff increases, which means that water from the snowmelt in the spring, for example, is not absorbed by small polygon ponds in the tundra but rather is rapidly flowing towards streams and larger rivers via the newly developing hydrological networks along thawing ice wedges”. The experts produced models which suggest the Arctic will lose many of its lakes and wetland areas if the permafrost retreats.

Co-author Guido Grosse, also from AWI, says the thaw is much more significant that it might first appear. The changes to the flow pattern also change the biochemical processes which depend on ground moisture saturation, he says.

The permafrost contains huge amounts of frozen carbon from dead plant matter. When the temperature rises and the permafrost thaws, microorganisms become active and break down the previously trapped carbon. This in turn produces the greenhouse gases methane and carbon dioxide. This is a topic already well researched, at least with regard to slow and steady temperature rises and thawing of near-surface permafrost, the authors say. But the thawing of these deep ice wedges will lead to massive local changes in patterns. “The future carbon balance in the permafrost regions depends on whether it will get wetter or dryer. While we are able to predict rainfall and temperature, the moisture state of the land surface and the way the microbes decompose the soil carbon also depends on how much water drains off”, says Julia Boike.

Now the results of the research have to be integrated into large-scale models.

The study of the impacts of thawing ice wedges seems to me like a good metaphor for the relation between Arctic climate change and what’s happening to the planet as a whole. Something changes in a localised area, which turns out to have far greater significance for a much wider area of the planet (or even the whole).

Feedback