Search Results for Tag: Zackenberg

Olympics over, but Arctic ice still chasing records

The Rio games have come to an end. Summer is drawing to a close here in Germany. It feels more like autumn today, cool with heavy rainshowers. But there’s a heatwave around the corner after what most people agree has been a very strange summer.

July followed in the record-breaking trend of the earlier months of the year, being the hottest month ever recorded on the planet.

![]() read more

read more

Arctic future: not so permafrost

“A glance into the future of the Arctic” was the title of a press release I received from the Alfred Wegener Institute this week, relating to the permafrost landscape.

“Thawing ice wedges substantially change the permafrost landscape” was the sub-title.

“I felt the earth move under my feet…” was the song line that came to my mind.

The study was led by Anna Liljedahl of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. And Fairbanks is, indeed, where I would like to have been this past week, with Arctic Science Summit Week taking place.

Arctic Council in Fairbanks

Clearly the Arctic Council thought the same and actually managed to put their wish into practice by holding a meeting of the Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs) there from March 15th to 17th. The agenda focused to a large extent, it seems, on climate change, and “placing the Council’s overall work on climate change in the context of the COP21 climate agreement” reached in Paris in December, according to a media release.

“The Council needs to consider how it can continue to evolve to meet the new challenges of the Arctic, particularly in light of the Paris Agreement on climate change. We took some steps in that direction this week”, said Ambassador David Balton, Chair of the SAOs.

Now what exactly does that mean? The Working Groups reported “progress on specific elements”. They include the release of a new report on the Arctic freshwater system in a changing climate, “cross-cutting efforts aimed at preventing the introduction of invasive alien species”, strengthening the region’s search and rescue capacity, efforts to support a pan-Arctic network of marine protected areas and promoting “community-based Arctic leadership on renewable energy microgrids”. I suppose those could be part of the process. Clearly there are a lot of interesting things going on.

NOAA’S latest – not so cheery

Against the background of NOAA’s latest revelations on global temperature development, though, they may have to speed up the pace. The combined average temperature over global land and ocean surfaces for February 2016 was the highest for February in the 137-year period of record, NOAA reports, at 1.21°C (2.18°F) above the 20th century average of 12.1°C (53.9°F). This was not only the highest for February in the 1880–2016 record—surpassing the previous record set in 2015 by 0.33°C / 0.59°F—but it surpassed the all-time monthly record set just two months ago in December 2015 by 0.09°C (0.16°F).

Overall, the six highest monthly temperature departures in the record have all occurred in the past six months. February 2016 also marks the 10th consecutive month a monthly global temperature record has been broken. The average global temperature across land surfaces was 2.31°C (4.16°F) above the 20th century average of 3.2°C (37.8°F), the highest February temperature on record, surpassing the previous records set in 1998 and 2015 by 0.63°C (1.13°F) and surpassing the all-time single-month record set in March 2008 by 0.43°C (0.77°).

Here in Germany, the temperature was 3.0°C (5.4°F) above the 1961–1990 average for February. NOAA attributes it to a large extent to strong west and southwest winds. Now that is a big difference, and I can certainly see it in nature all around. But the difference was more than double that in Alaska. Alaska reported its warmest February in its 92-year period of record, at 6.9°C (12.4°F) higher than the 20th century average.

Why worry about wedges?

So, back to Fairbanks, or at least to the changing permafrost in this rapidly warming climate, which was on the agenda there at the Arctic Science Summit Week. (See webcast.)

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, conducted by an international team in cooperation with the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (no wonder we prefer to call them AWI), indicates that ice wedges in permafrost throughout the Arctic are thawing at a rapid pace. The first thought that springs to my mind is collapsing buildings, remembering seeing cooling systems in Greenland to keep the foundations of buildings in the permafrost frozen and so stable. Of course that only affects areas which are built upon (certainly bad enough). The new study looks at what the melting ice wedges will mean for the hydrology of the Arctic tundra. And that impact will be massive, the scientists say.

The ice wedges go down as far as 40 metres into the ground and have formed over hundreds or even thousands of years, through freezing and melting processes. Now the researchers have found that even very brief periods of above-average temperatures can cause rapid changes to ice wedges in the permafrost near the surface. In nine out of the ten areas studied, they found that ice wedges thawed near the surface, and that the ground subsided as a result. So, once more, humankind is changing what nature created over thousands of years in a very short space of time. I am reminded of a recent study indicating that our greenhouse gas emissions have even postponed the next ice age.

A dry future for the Arctic?

“The subsiding of the ground changes the ground’s water flow pattern and thus the entire water balance”, says Julia Boike from AWI, who was involved in the study. “In particular, runoff increases, which means that water from the snowmelt in the spring, for example, is not absorbed by small polygon ponds in the tundra but rather is rapidly flowing towards streams and larger rivers via the newly developing hydrological networks along thawing ice wedges”. The experts produced models which suggest the Arctic will lose many of its lakes and wetland areas if the permafrost retreats.

Co-author Guido Grosse, also from AWI, says the thaw is much more significant that it might first appear. The changes to the flow pattern also change the biochemical processes which depend on ground moisture saturation, he says.

The permafrost contains huge amounts of frozen carbon from dead plant matter. When the temperature rises and the permafrost thaws, microorganisms become active and break down the previously trapped carbon. This in turn produces the greenhouse gases methane and carbon dioxide. This is a topic already well researched, at least with regard to slow and steady temperature rises and thawing of near-surface permafrost, the authors say. But the thawing of these deep ice wedges will lead to massive local changes in patterns. “The future carbon balance in the permafrost regions depends on whether it will get wetter or dryer. While we are able to predict rainfall and temperature, the moisture state of the land surface and the way the microbes decompose the soil carbon also depends on how much water drains off”, says Julia Boike.

Now the results of the research have to be integrated into large-scale models.

The study of the impacts of thawing ice wedges seems to me like a good metaphor for the relation between Arctic climate change and what’s happening to the planet as a whole. Something changes in a localised area, which turns out to have far greater significance for a much wider area of the planet (or even the whole).

Arctic investment: still a hot prospect?

As I mentioned in the last post, I talked to various people about the current state of interest in the Arctic, in connection with the ArcticNet conference on “Arctic Change” in Ottawa last week. I would like to share some of the insights I gained with you here on the Ice Blog. With a lot of concerned people still suffering from a kind of mental hangover after the two weeks of UN climate negotiations in Lima, let me also direct you to a commentary I wrote for DW: Lima: a disappointment, but not a surprise. If you expected any action at the meeting which might help stop the Arctic warming, you will have been highly disappointed. If, like me, you think the transition to renewables and emissions reductions we need have to happen outside of and alongside that process, all day and every day, your expectations will not have been so high.

But back to the Arctic itself. With Canada coming to the end of its spell at the helm of the Arctic Council and preparing to hand over the rotating presidency to the USA at the end of the year, the annual conference organized by the research network ArcticNet was bound to attract a lot of interest. More than 1200 leading international Arctic researchers, indigenous leaders, policy makers, NGOs and business people attended the Ottawa gathering to discuss the pressing issues facing the warming Arctic.

Hugues Lantuit from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute is a member of the steering committee. He’s an expert on permafrost and coastal erosion. He told me in an interview that the region had to prepare for greater impacts ,with the latest IPCC report projecting the Arctic would continue to warm at a rate faster than any place on earth. While the retreat of sea ice allows easier access for shipping and more scope for commercial activities, Lantuit is concerned about the thawing of permafrost, a key topic at the Ottawa gathering:

“An extensive part of the circumpolar north is covered with permafrost, and it’s currently warming at a fast pace. A lot of cities are built on permafrost, and the layer that is thawing in the summer is expanding and getting deeper and deeper, which threatens infrastructure.”

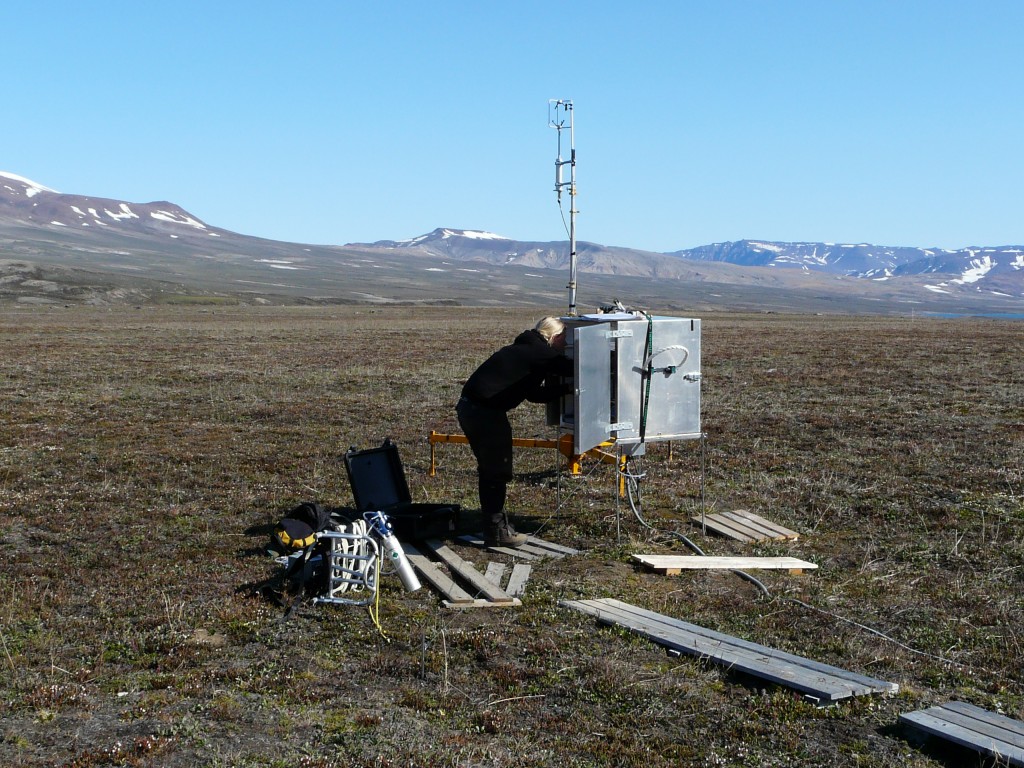

Scientists at measuring stations like the one I viisted at Zackenberg, Greenland, measure the amount of greenhouse gases emitted by melting permafrost. (I.Quaile)

Northern communities worried

Residents of northern communities are concerned about the impact of melting permafrost on railways, landing strips and buildings. Lantuit and his colleagues have created an integrated data base for permafrost temperature, with support from the EU. At the Ottawa meeting, he and his colleagues worked on identifying priorities for research, taking into account the needs of communities and stakeholders in the Arctic.

Another key issue on the Ottawa agenda was coastal erosion. Sea ice acts as a protective barrier to the coast, preventing waves from battering the shore and speeding up the thaw of permafrost. With decreasing sea ice in the summer, scientists expect more storms will impact on the coasts of the Arctic. “In some locations, especially in Alaska, we see much greater erosion than there was before”, says Lantuit. This creates a lot of issues: “There is oil and gas infrastructure on the coast, villages, people, also freshwater habitats for migrating caribou, so the coast has a tremendous social and ecological value in the Arctic, and coastal erosion is obviously a threat to settlements and to the features of this social and economical presence in the Arctic.”

Bad news for furred and feathered friends

Amongst the participants at the conference was George Divoky, an ornithologist who has spent every summer of the past 45 years on Cooper Island, off the coast of Barrow, in Arctic Alaska. Divoky monitors a colony of black guillemots that nest on the island in summer. His bird-watching project turned into a climate change observation project as he witnessed major changes in the last four decades:

“Warming first aided the guillemots (1970s and 1980) as the summer snow-free period increased. The size of the breeding colony increased during the initial stages of warming. Continued warming (1990s to present) caused the sea ice to rapidly retreat in July and August when guillemots are feeding nestlings, and the loss of ice reduced the amount and quality of prey resulting in widespread starvation of nestlings.”

The 2014 breeding season on Cooper Island had the lowest number of breeding pairs of Black Guillemots on the island in the last 20 years, Divoky says. Reduced sea ice is increasingly forcing polar bears to seek refuge on the island, eating large numbers of nestlings. Polar bears were rare visitors to the island until 2002.

The Arctic and the global climate

Divoky went to Ottawa to fit his research and experience into the wider context of climate impacts in the Arctic. Researching climate change and its effects are important but of little practical use if the research does not inform government officials and result in policies that address the causes of climate change, Divoky argues.

I asked Hugues Lantuit whether he thought the UN climate conference in Peru could achieve anything that would halt the warming of the Arctic. He said reducing emissions and reducing temperature were the only way to reduce the thaw of permafrost. But he is quite clear about the fact that there is no mitigation strategy in terms of permafrost directly. “You would have to put a blanket over the entire permafrost in the northern hemisphere. This is not possible.”

At the same time, he stressed the key role of the Arctic with regard to the whole world climate: “Permafrost contains a lot of what we call organic carbon, and that is stored in the upper part. And if that warms, the carbon is made available to microorganisms that convert it back to carbon dioxide and methane. And we estimate right now that there is twice as much organic carbon in permafrost as there is in the atmosphere”.

So far, the international community has not been able to take measures to break that vicious circle.

What happened to the Arctic gold rush?

Communities who live and companies that work in the Arctic have to focus on adaptation to the rapid change, says Lantuit. In his eyes, economic activity is increasing, posing new challenges for infrastructure and the environment.

Malte Humpert, the Executive Director of the Arctic Institute, a non-profit think tank based in Washington DC has a different view on the matter. He says while attendance at Arctic conferences and interest in the Arctic is still high, commercial activity has actually been cooling off. “We are seeing a slow-down of investment. Up to this point there has been a lot of studying, a lot of interest being voiced, with representatives from China or South Korea, Japan, Singapore or other actors, arriving at conferences, speaking about grand plans. But up to this point a lot of the talk has been just that.” A lot of activity has been put on hold, says Humpert. He says the “gold rush mentality we saw a few years ago” has weakened. “There was a lot of talk about Arctic shipping initially, then we had oil and gas activity in 2012, north of Alaska, then we had the discussion about minerals in Greenland. The question is now, with the oil price being down below 70$ a barrel, some political uncertainties over the Ukraine, involving the EU and Russia, how will that affect Arctic development?”

Humpert stresses the Arctic does not exist in a vacuum, but has to be seen within the global context. Sanctions on Russia because of the Ukraine crisis have created economic problems for Moscow and limited access to technology it might need for its Arctic activities. “Maybe Arctic development has been oversold and overplayed and will be more of a niche operators’ investment. One could definitely question if there will be this global push into the Arctic.”

Arctic development on ice

Humpert is skeptical that any major development will take place before 2030. He says developing the infrastructure in terms of ports and communications in the remote Arctic region would require billions of dollars of investment, and would have to be a very long-term proposition. It will also depend to a large extent on exactly how climate change affects ice conditions in the Arctic. Climate change can make the climatic conditions in the Arctic more variable. This means that for a temporary period, there might even be more ice, which would block transport routes.

The Arctic Institute says there has actually been a slow down this year in terms of navigation on the northern sea route (NSR) in particular: “The season just closed about a week ago. Last year we had 1.35 million tonnes of cargo being transported along the NSR, this year we had less than 700,000 tonnes, so an almost 50% decrease, just because there was more ice in the way”, says Humpert.

Whether slower development is good news or bad depends on your perspective. The lull in Arctic activity could pre-empt environmental degradation or destruction, says Humpert, and leave scope to consider development of the Arctic in what he calls a 21st century way. Instead of “old-school” thinking about extracting minerals, oil and gas and increasing shipping, there could be a focus on bringing modern, high-speed communications, fiber optics and thinking about renewables, such as wave energy. This would benefit the small populations in the Arctic, the expert argues.

But from the viewpoint of a country like Russia, he adds, where 40 percent of your exports are generated above the Arctic circle, in terms of hydrocarbon resources, the slowdown in Arctic development because of the drop in oil prices and political tensions over Ukraine is very worrying.

So while these developments seem to have brought the Arctic a breathing space, ultimately, the commercialization of the region could be just a matter of time. Ottawa conference organizer Lantuit argues that there has always been activity in the high North. The priority now, he says, must be to ensure international cooperation and additional investment in protecting the environment and maintaining safety in a region where rapid change seems to have become the status quo.

Arctic birds breeding earlier

Migratory birds that breed in the Arctic are starting to nest earlier in spring because the snow melt is occurring earlier in the season. This is confirmed by a new collaborative study,”Phenological advancement in arctic bird species: relative importance of snow melt and ecological factors” published in the current online edition of the journal Polar Biology. The scientists, including Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) biologists, looked at the nests of four shorebird species and one songbird in Alaska, recording when the first eggs were laid in the nests. The work was undertaken across four sites ranging from the oilfields of Prudhoe bay to the remote National Petroleum Reserve of western Arctic Alaska.

The scientists looked at nesting plots at different intervals in the early spring. Other variables, like the abundance of nest predators (which is thought to affect the timing of breeding) and satellite measurements of “greenup” (the seasonal flush of the new growth of vegetation) in the tundra were also assessed as potential drivers, but were found to be less important than snow melt.

Lead author Joe Liebezeit from the Audubon Society of Portland says “it seems clear that the timing of the snow melt in Arctic Alaska is the most important mechanism driving the earlier and earlier breeding dates we observed in the Arctic. The rates of advancement in earlier breeding are higher in Arctic birds than in other temperate bird species, and this accords with the fact that the Arctic climate is changing at twice the rate.”

Over nine years, the birds advanced their nesting by an average of 4-7 days. The researcher says this fits with the general observation of 0.5 days per year observed in other studies of nest initiation in the Arctic, of which, they say, there are not very many. The rates of change are much higher than those of observed in studies of temperate birds south of the Arctic.

Co-author Steve Zack from WCS says “Migratory birds are nesting earlier in the changing Arctic, presumably to track the earlier springs and abundance of insect prey. Many of these birds winter in the tropics and might be compromising their complicated calendar of movements to accommodate this change. We’re concerned that there will be a threshold where they will no longer be able to track the emergence of these earlier springs which may impact breeding success or even population viability”.

WCS Beringia Program Coordinator Martin Robards says “Everything is a moving target in the Arctic because of the changing climate. Studies like these are valuable in helping us understand how wildlife is responding to the dramatic changes in the Arctic ecosystem. The Arctic is so dramatically shaped by ice, and it is impressive how these long-distance migrants are breeding in response to the changes in the timing of melting ice.”

In connection with Migratory Bird Day some time ago, I talked to Ferdinand Spina, head of Science at Italy’s National Institute for Wildlife Protection and Research ISPRA, in Bologna, Italy. He is also in charge of the Italian bird ringing centre, and Chair of the Scientific Council of the UN Convention on Migratory Species, CMS. In the interview, he stressed that climate change is becoming one of the greatest threats to birds that breed in the Arctic.

“Birds are a very important component of wildlife in the Arctic. There are different species breeding in the Arctic. The Arctic is subject to huge risks due to global warming. It is crucially important that we conserve such a unique ecosystem in the world. Birds have adapted to living in the Arctic over millions of years of evolution, and it’s a unique physiological and feeding adaptation. And it is our duty to conserve the Arctic as one of the few if not the only ecosystems which is still relatively intact in the world. This is a major duty we have from all possible perspectives, including an ethical and moral duty, ” he says. We talked about the seasonal mismatch, when birds arrive too early or too late to find the insects they expect to encounter and need to feed their young.

This reminds me of a visit to Zackenberg station in eastern Greenland in 2009. At that time, Lars Holst Hansen, the deputy station leader, told me the long-tailed skuas were not breeding because they rely on lemmings as prey. The lemmings were scarce because of changes in the snow cover.

Jeroen Reneerkens is another regular visitor to Zackenberg, as he tracks the migration of sanderlings between Africa and Greenland. A great project and an informative website!

Morten Rasch from the Arctic Environment Dept of Aarhus University in Denmark is the coordinator of one of the most ambitious ecological monitoring programmes in the Arctic. The Greenland Environment Monitoring Programme includes 2 stations, Zackenberg, which is in the High Arctic region and Nuuk, Greenland’s capital, in the “Lower” Arctic. Hansen and other members of Rasch’s teams monitor 3,500 different parameters in a cross-disciplinary project, combining biology, geology, glaciology, all aspects of research into the fragile eco-systems of the Arctic. At that time, he told me during an interview, ten years of monitoring had already come up with worrying results:

“We have experienced that temperature is increasing, we have experienced an increasing amount of extreme flooding events in the river, we have experienced that phenology of different species at the start-up of their growing season or the appearance of different insects for instance now comes at least 14 days earlier than when we started. And for some species, even one month earlier. And that’s a lot. You have to realise the entire growing season in these areas is only 3 months. When we start up at Zackenberg in late May, or the beginning of June, the ecosystem is completely covered in snow and more or less frozen, and when we leave, in normal years – or BEFORE climate change took over – then we left around 1st September and the ecosystem actually started to freeze up. So the entire biological ecosystem only has 3 months to reproduce and so on. And in relation to that, a movement in the start of the system between 14 days and one month – that’s a lot.”

Listen to my radio feature: Changing Arctic, Changing World

I can’t write about birds and climate change in the Arctic without finishing off with a mention of George Divoky, an ornithologist whose bird-monitoring has actually turned into climate-change monitoring on Cooper Island, off the coast of Barrow, Alaska. George looks after a colony of Black Guillemots and spends his summer on the island. In recent years, he has taken to putting up bear-proof nest boxes for the birds, because polar bears increasingly come to visit, as the melting of the sea ice has reduced their hunting options. He has also observed the presence of new types of birds which die not previously come this far north.

Biodiversity Day: The Arctic

- Svalbard reindeer, Ny Alesund

May 22 is the UN official “International Day for Biological Diversity (IDB)”. Yes, I know, I frequently wonder about the value of these “International Day of…” whatever, but usually come to the conclusion that it’s always good to have reminders or pegs to draw attention to issues that don’t always make the headlines (last time on Migratory Bird day, see Ice Blog post). May 22 was chosen because it was the day, in 1992, when the text of the Convention on Biological Diversity was adopted in Nairobi.

Anyway, at least in our northern hemisphere, May is a good time to talk about biodiversity, as nature bursts into life (or creeps out gently with the temperatures in my part of Europe currently a little on the chilly side) after the winter rest. Like so many things in our world, this is also affected by climate change, with increasing variability in temperature and conditions having an impact on the seasons.

This May also sees the publication of the “Arctic Biodiversity Assessment“. It was released at the meeting of the Arctic Council in Kiruna on May 15th. Let me quote a little from the intro, which sums up why Arctic biodiversity is so special:

“The Arctic holds some of the most extreme habitats on Earth, with species and peoples that have adapted through biological and cultural evolution to its unique conditions. A homeland to some, and a harsh if not hostile environment to others, the Arctic is home to iconic animals such as polar bears Ursus maritimus, narwhals Monodon monoceros, caribou/reindeer Rangifer tarandus, muskoxen Ovibos moschatus, Arctic fox Alopex lagopus, ivory gull Pagophila eburnea and snowy owls Bubo scandiaca, as well as numerous microbes and invertebrates capable of living in extreme cold, and large intact landscapes and seascapes with little or no obvious sign of direct degradation from human activity. In addition to flora and fauna, the Arctic is known for the knowledge and ingenuity of Arctic peoples, who thanks to great adaptability have thrived amid ice, snow and winter darkness… The Arctic is made up of the world’s smallest ocean surrounded by a relatively narrow fringe of island and continental tundra. Extreme seasonality and permafrost, together with an abundance of freshwater habitats ranging from shallow tundra ponds fed by small streams to large deep lakes and rivers, determine the hydrology, biodiversity and general features of the Arctic’s terrestrial ecosystems. Seasonal and permanent sea ice are the defining features of the Arctic’s marine ecosystems.”

Biodiversity loss is happening at a frightening rate all over the globe, and the Arctic is no exception. On the contrary, with the climate there warming so much faster than the global average, Arctic biodiversity is under terrific pressure. As a contribution to halting the loss of biodiversity, the Arctic Council initiated the Arctic Biodiversity Assessment, consulting scientists on what could be done to alleviate pressures on Arctic biodiversity. The report gives an overview of the stress factors putting Arctic biodiversity and suggests possible actions to enhance biodiversity conservation.

The authors stress that there are substantial gaps in our knowledge of Arctic biodiversity. There is a huge need for continuing research.

Climate change is clearly a major problem. Melting ice, melting permafrost, warmer ocean – clearly such changes to some of the defining factors influence living conditions for flora and fauna too. With warming paradoxically making it easier to indulge in activities in the far north which could exacerbate climate change even further, the situation is complex and the time pressure huge.

Reports of this kind are usually very hard to read. I must commend the authors for the online presentation of this one. It’s divided into readable chapters and has some spectacular pictures. Some were taken by Lars Holst Hansen at Zackenberg, Greenland. I met and interviewed Lars at Zackenberg Station in north-eastern Greenland in 2009. The radio feature I made at that time is still very relevant and describes work at the remote research station, which monitors a wide range of environmental parameters, including of course, lots of biodiversity.

LISTEN: Changing Arctic, Changing World: Greenland’s Changing Climate.

I went counting musk oxen with Lars while I was at the station. One of his photos of the “big hairy beasties” is actually being used on a stamp incidentally. Congratulations Lars for the brilliant picture and for this contribution to spreading the word about the need to protect the fragile Arctic environment and its biodiversity.

Feedback