Search Results for Tag: Media

New report sees Arctic melt on course to tip global climate

Scientists say the Arctic archipelago of Svalbard has seen such extreme warmth this year that the average annual temperature could end up above freezing for the first time on record. Ketil Isaksen of the Norwegian Meterological Institute said today the average temperature in Longyearbyen, the main settlement in Svalbard, is expected to be around 0 Celsius with a little over a month left of the year. He called the abnormal warmth “shocking” and beyond anything he could have imagined 10 years ago. The normal yearly average is minus 6.7 C.

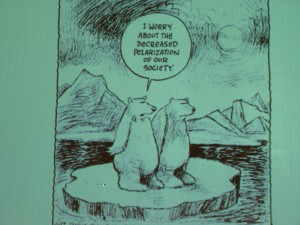

And that is not the only shocking thing going on up north. The Arctic sea ice is melting in November. Temperatures in the region are 20 degrees Celsius above usual. Reindeer are dying across Siberia. Polar bears are stranded on land. It’s hard to keep up with the extent and speed of climate change in the far north of the planet. And we in the media have to be aware of the danger that the reports become so commonplace the “new normal” no longer arouses interest.

Svalbard’s sturdy reindeer are adapting to climate change. In Siberia, thousands of animals have died of starvation. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Warming, warming, hot

Yet the ever faster melting of our Arctic ice could spell disaster even for distant regions of the planet. What happens in the Arctic doesn’t stay in the Arctic, as discussed here on the Ice Blog many times before. But a new, key report launched today indicates that the effects of increasingly rapid Arctic warming could be set to push global climate change out of control.

The Arctic Resilience Assessment (ARA) is an Arctic Council project led by the Stockholm Environment Institute and the Stockholm Resilience Centre. It is based on collaboration with Arctic countries and Indigenous Peoples in the region, as well as several Arctic scientific organizations. The ARA (previously Arctic Resilience Report) was initiated by the Swedish Ministry of the Environment as a priority for the Swedish Chairmanship of the Arctic Council (May 2011 to May 2013) and is being presented under the US Chairmanship. It aims to synthesize knowledge on Arctic change and how people and the ecosystem are coping with it, bringing the wide range of different factors together.

“Environmental, ecological, and social changes are happening faster than ever in the Arctic, and are accelerating. They are also more extreme, well beyond what has been seen before. This means the integrity of Arctic ecosystems is increasingly challenged, threatening the sustainability of current ways of life in the Arctic and disruption of global climate and ecosystems”, the report says.

Beyond the tipping point

The researchers issue a stark warning: “Some changes are so substantial (and often abrupt), that they fundamentally alter the functioning of the system: an ecological “tipping point” has been crossed. The report examines 19 of these “tipping points” or “regime shifts”, as they are also known: “They affect many ecosystem services that are important to people within and outside the Arctic: from regulating the climate, to providing sustenance (e.g. through fishing)”, the experts tell us.

“The consequences of some of these shifts are likely to be surprising and disruptive – particularly when multiple shifts occur at once. By altering existing patterns of evaporation, heat transfer and winds, the impacts of Arctic regime shifts are likely to be transmitted to neighbouring regions such as Europe, and impact the entire globe through physical, ecological and social connections”, the report says.

The tipping points discussed in the report include the replacement of white ice and snow, which reflect heat back into space, by darker green vegetation or ocean water, which absorbs more heat, higher releases of methane and changes to ocean circulation and so weather patterns around the globe caused by an influx of melting snow and ice.

Major impacts inevitable?

Johan Rockström, director of the Stockholm Resilience Centre and co-chair of the five-year study said in a statement: “If multiple regime shifts reinforce each other, the results could be potentially catastrophic.… The variety of effects that we could see means that Arctic people and policies must prepare for surprise. We also expect that some of those changes will destabilize the regional and global climate, with potentially major impacts”.

The report stresses that many of the changes and feedback effects in process are poorly understood and in need of much more research.

“Arctic ecological protection is now a global concern, and worldwide monitoring is inadequate”, the authors write.

Political “regime shift”?

To reduce the risk of these tipping points, strong action would have to be taken to mitigate climate change, the authors conclude. Aha. Now there’s the rub.

In the Guardian, Fiona Harvey notes the report comes at a critical time in politics, with Donald Trump’s announcement this week that he plans to take away NASA’s budget for climate science and put it into space exploration. She quotes Marcus Carson of the SEI, co-editor of the report:

“That would be a huge mistake…It would be like ripping out the aeroplane’s cockpit instruments while you are in mid-flight”.

If Mr. Trump also makes good his pledge to revive the US coal industry and abandon the Paris Climate Agreement, the chances of halting warming and the climate feedback mechanisms which could spell disaster would seem to be melting away along with that Arctic ice. Not so tasty food for thought this weekend. Well, I could distract myself by getting out the lawnmower. It has been so warm here this week the birds are chirping like spring and the grass has started to grow again.

Can Paris avert climate threat to cryosphere?

To those of us who work on polar subjects, there is no question about the relevance of the cryosphere to the annual UN climate negotiations. But in the run-up to the annual mega-event – especially in a year dubbed by some to be the “last chance” for climate – it was not easy to get attention for the Arctic, Antarctic and high-altitude peaks and glaciers of the world.

I had a discussion with some of my colleagues who focus on Africa and Asia. With problems like political unrest, wars, famine and drought to cope with, the fate of polar bears, one told me, is completely irrelevant.

You could say this colleague is suffering from a kind of tunnel vision. But it also prompts me to wonder whether the way we communicate the threat of climate change is partly to blame.

Not just polar bears

Earlier this week I read about a study indicating that people were more likely to donate to campaigns which focus on people, on social injustice rather than on conservation and environmental degradation. Somehow, we journalists have to make the connection between the two. When you remind people that increasing sea levels caused to a large extent by changes in our ice sheets pose a huge threat not only to small island states but to many of the world’s megacities, the cryosphere takes on a new relevance. Not to mention the fact that the ice, snow and permafrost covered regions of our planet play a major role in regulating the world’s climate and water supplies.

One organization that works to bring the attention of delegates at the UN climate talks to our icy regions is the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative, ICCI. In time for this year’s COP21, it commissioned a report from leading scientists: “Thresholds and closing windows. Risks of irreversible cryosphere climate change”. The report summarizes the levels of risk in five key areas: ice sheets loss and related sea-level rise, polar ocean acidification, land glacier loss, permafrost melt, and the loss of Arctic summer sea ice. The report is based on the last IPCC assessment plus literature published in the three years since.

Bringing the ice closer

Pam Pearson is the director and founder of ICCI. I have interviewed her on various occasions, including during visits she made to Bonn, the home of the UNFCCC, to brief delegates. This time we were not able to meet in person, but we have been in Email contact. I asked her how difficult it was to arouse interest within the negotiations at the moment, with so much going on. She told me it was difficult mainly because very few people globally actually live near cryosphere.

“Yet we are all deeply connected to these regions, because of their role in the Earth climate system — especially through sea-level rise, water resources from land glaciers, and permafrost release that will make it harder to meet carbon budgets. “

The Arctic, parts of Antarctica and many mountain regions have already warmed two to three times faster than the rest of the planet, between 2 and 3.5 degrees Celsius up on pre-industrial levels. Climate change is also affecting high altitude areas such as the Himalayas and the Andes, where seasonal glacier melt provides water for drinking and irrigation, especially in dry periods.

When the outside risk becomes the norm

The changes are far more extreme than those forecast in even the most pessimistic scenarios of a few years ago. In the IPCC’s 2007 Fourth Assessment, the outer extreme estimate for sea level rise (mostly from glacier ice melt) was about one meter by the end of this century. Today, the experts say even if we could halt warming now, it would be impossible to avoid sea-level rise of one meter from glaciers, ice sheets and the natural expansion of warming waters, within the next two hundred years. Most scientists also agree that the West Antarctic ice sheet has already been destabilized by warming to the extent where this probably cannot be halted, which will increase sea level further.

Pearson used to be a climate negotiator herself, so she knows the pressures and constraints. She told me that while participants in the climate conferences were broadly aware of issues like ice melt at the poles and on high-altitude glaciers, they tended to lack awareness of two key aspects:

“First, that we have already passed, or are close to passing temperature levels that will cause certain processes to begin; and second, that some of these processes cannot be stopped once they get started.”

She says a “sense of urgency” is lacking, and stresses that although some of the most damaging consequences will only occur in hundreds or even thousands of years, they will be determined by our actions or inactions in the coming few decades. That includes the 2020-30 commitment period that is the focus of the agreement being worked on in Paris Pearson stresses.

The cryosphere needs more ambitious targets

The report analyses the implications of the INDCs, or current pledges put on the table by the countries of the world for the Paris climate talks. The scientists come to the conclusion that these will not be enough to prevent the onset of many irreversible cryosphere processes.

Even the two-degree pathway agreed by the international community translates into a peak cryosphere temperature of between 4 and 7 degrees above pre-industrial levels, according to the ice experts. Yet the UN and others say current commitments would lead to global temperatures 2.7 to 3.5 degrees Celsius above pre-industrial levels by 2100, rising later to between 3.4 and 4.2 degrees. The peak in global carbon emissions would occur well after 2050. The associated temperatures would trigger permanent changes in our ice and snow that cannot be reversed, including the complete loss of most mountain glaciers, the complete loss of portions of West Antarctica’s Ice Sheets and parts of Greenland. This would ultimately equate to an unstoppable sea level rise of a minimum four to ten meters, the scientists find.

In addition, the increase of CO2 being absorbed in the Southern Ocean around Antarctica and the Arctic Ocean is turning the water more acidic and so threatening fisheries, marine ecosystems and species.

Another of the key issues which is often neglected is that of permafrost. About a quarter of the Northern Hemisphere’s land area contains ground that remains frozen throughout the year. This holds vast amounts of ancient organic carbon. So when it thaws, carbon dioxide and methane are released, which fuel further warming. Even a temperature rise of 1.5 degrees could result in a 30% loss of near-surface permafrost. This would mean 50 Gigatonnes of additional carbon emissions by 2100. Given that the total carbon budget allocated to a two-degree temperature rise is only 275 Gigatonnes, that would be a huge factor. The ICCI experts say this thaw would not be reversible, except on geological time scales.

Dwindling Arctic sea ice

Arctic summer sea ice has declined rapidly, especially since 2000. Only about half the sea ice survives the summer today compared to 1950. This is “both a result and a cause of overall Arctic and global warming”, according to the ICCI report. White ice reflects heat into space. When it melts, it is replaced by dark water, which absorbs the heat, exacerbating warming further.

The Arctic sea ice has a tempering effect on global temperatures and weather patterns. It would only be possible to reverse the disappearance of the ice in summer with a return to regular global temperatures of 1 to 2 degrees above pre-industrial times, according to the report.

Andes and Himalayas

Receding mountain glaciers in the European Alps, American Rockies, Andes and East Africa were among the first identified, visible impacts of climate change, originally from natural factors. Sometime in the past 50 years, anthropogenic climate change surpassed natural warming as the main driver of retreat, and caused about two-thirds of glacier melt between 1991 and 2010, according to the ICCI report.

Glaciers – beautiful but highly endangered, like this one I visit regularly in the Swiss alps. (Pic. I.Quaile)

Glaciers are important to nearby communities as a source of water for drinking or irrigation. Some are especially important in dry seasons, heat waves and droughts. Melting glaciers provide an increase in water for a limited time. But ultimately, the lack of water could make traditional agriculture impossible in some regions of the Himalayas or the Andes.

So unless governments in Paris move fast to increase their commitments and bring the deadlines for emissions reductions forward, the windows to prevent some of these irreversible impacts on the polar and high mountain regions may close during the 2020-2030 commitment period.

It is not too late

However, the scientists stress that it is still possible to reduce emissions to the required level, if the political will becomes strong enough. Pam Pearson says the world has to get onto the path towards the two-degree goal now. Like many experts, she says this in itself is risky enough for the cryosphere, and a 1.5 degree pathway would be safer:

“So if countries indeed agree with UNFCCC chief Christiana Figueres’ proposal to meet every five years to strengthen INDCs, moving onto these lower-temperature pathways should be a concrete goal. Perhaps even more important, I understand the French COP presidency may be aiming at strengthening actions PRIOR to 2020, in the 2015-2020 period. This kind of earlier action is really vital, and will make the job of keeping temperatures as low as possible easier”

Without much more ambitious targets, the ICCI study concludes it will be “close to impossible” to avoid rapid deterioration of our snow and ice regions.

The challenge is to make the delegates in Paris understand that that does not just mean cosmetic changes to distant parts of the globe, but that it would also destabilize the global climate, displace millions of people and endanger food and water supplies in many parts of the world.

Keeping Greenland in focus

Two interesting publications relating to Greenland caught my eye over the past few days. But it has not proved easy to get them onto the international news agenda. Given the huge importance of the Greenland ice sheet to the planet’s future, this is frustrating to say the least. Fortunately there is the Ice Blog.

The first research relates to a study about the role of ash from fires in bringing about large-scale surface melting. The other predicts Greenland will be a far greater contributor to sea rise than expected.

Let me start with the latter, published in Nature Geoscience. Scientists from the University of California – Irvine and NASA glaciologists have found previously uncharted long deep valleys under the Greenland Ice Sheet. Since these bedrock canyons are well below sea level, they are much more vulnerable to warm ocean waters than previously thought. When warmer Atlantic water hits the fronts of hundreds of glaciers, the edges will erode much further than previously assumed, releasing far greater amounts of water.

Ice melt from the subcontinent has already accelerated, as warmer marine currents have migrated north, the authors say. Older models predicted that once higher ground was reached in a few years, the ocean-induced melting would halt. Greenland’s frozen mass would stop shrinking, and its effect on higher sea waters would be curtailed.

“That turns out to be incorrect. The glaciers of Greenland are likely to retreat faster and farther inland than anticipated – and for much longer – according to this very different topography we’ve discovered beneath the ice,” says lead author Mathieu Morlighem, a UC Irvine associate project scientist, on the university website. “This has major implications, because the glacier melt will contribute much more to rising seas around the globe.”

To obtain the results, Morlighem developed what he says is a breakthrough method that for the first time offers a comprehensive view of Greenland’s entire periphery. It’s nearly impossible to accurately survey at ground level the subcontinent’s rugged, rocky subsurface, which descends as much as 3 miles beneath the thick ice cap.

Since the 1970s, limited ice thickness data has been collected via radar pinging of the boundary between the ice and the bedrock. Along the coastline, though, rough surface ice and pockets of water cluttered the radar sounding, so large swaths of the bed remained invisible.

Measurements of Greenland’s topography have tripled since 2009, thanks to NASA Operation IceBridge flights. But Morlighem says he quickly realized that while that data provided a fuller picture than the earlier radar readings, there were still major gaps between the flight lines.

To reveal the full subterranean landscape, he designed a novel “mass conservation algorithm” that combined the previous ice thickness measurements with information on the velocity and direction of its movement and estimates of snowfall and surface melt.

The difference was dramatic, says Morlighem. What appeared to be shallow glaciers at the very edges of Greenland are actually long, deep fingers stretching more than 100 kilometers (almost 65 miles) inland.

“We anticipate that these results will have a profound and transforming impact on computer models of ice sheet evolution in Greenland in a warming climate,” the researchers conclude.

“Operation IceBridge vastly improved our knowledge of bed topography beneath the Greenland Ice Sheet,” said co-author Eric Rignot of UC Irvine and NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory. “This new study takes a quantum leap at filling the remaining, critical data gaps on the map.”

Other co-authors are Jeremie Mouginot of UC Irvine and Helene Seroussi and Eric Larour of JPL. Funding was provided by NASA.

This is the same team that reported on accelerated glacial melt in West Antarctica, as discussed in an earlier Ice Blog post. Together, the papers “suggest that the globe’s ice sheets will contribute far more to sea level rise than current projections show,” Rignot said.

Indeed. These scientists are telling us the IPCC forecasts were way too low. This could have huge consequences for coastal communities all around the globe.

Unfortunately, a lot of people (even those you would expect to know better) tend to mix up “Arctic” and “Antarctic”. It all goes into the category of “melting ice”, and they think they have heard it all before. What they still don’t realize is that this is something that concerns us all, and that these two polar areas are of huge significance to the world climate as a whole and global sea level. When those two Antarctic studies were released, there was a flurry of news coverage. The challenge for us journalists is how to follow this up and stop the attention curve from dropping.

The other interesting piece of recent Greenland research was conducted by the Dartmouth College Thayer School of Engineering and the Desert Research Institute and reported in the Proceedings of the National Academy of

Sciences. It concludes that ash from Northern hemisphere forest fires combined with rising temperatures to cause large-scale surface melting of the Greenland ice sheet in 1889 and 2012.

The researchers say their findings contradict conventional thinking that the melting was driven by warming alone.

The findings suggest that continued climate change will result in nearly annual widespread melting of the ice sheet’s surface by the year 2100.

Melting in the dry snow region does not contribute to sea level rise, but when the meltwater percolates into the snowpack and refreezes, the surface is less reflective. This reduces the albedo.

Let me give the (almost) last word to the study’s lead author Kaitlin Keegan.

“With both the frequency of forest fires and warmer temperatures predicted to increase with climate change, widespread melt events are likely to happen much more frequently in the future”.

It figures.

Climate change back on the agenda?

Trawling the media for climate-related stories over the weekend, I began to see some signs that the message might be getting across after all. I had just put the finishing touches to my story on “Why we don’t want to hear about climate change“, based on interviews with sociologist Kari Marie Norgaard from the University of Oregon and psychologist Per Stoknes from the Norwegian Business school, when I heard US Secretary of State John Kerry’s announcement that the USA and China would be cooperating and exchanging data in the run-up to the 2015 Paris climate talks, where a new climate deal is supposed to be agreed. I found myself feeling just a little bit more optimistic. If these two key players really put climate protection into action, maybe we will be able to get somewhere. A report on a study by the Chinese government on the disastrous air pollution in Beijing is not happy reading, but gives grounds to assume the Chinese government has to be serious about taking emissions in hand.

Arctic ambassador – a sign of the times?

Another announcement by the US Sec of State leaves me with mixed feelings. There is going to be a US ambassador for the Arctic. On the one hand, it is always good to see the Arctic getting attention. On the other hand, the motivation does not make me jump for joy. An item from the news agency AFP writes of “a region increasingly coveted by several countries for its oil and other raw materials”. Indeed. That is the worrying bit. In case you missed it, (the Arctic announcement did not get huge coverage), Kerry said in his statement:

“The Arctic region is the last global frontier and a region with enormous and growing geostrategic, economic, climate, environment and national security implications for the United States and the world…President Obama and I are committed to elevating our attention and effort to keep up with the opportunities and consequences presented by the Arctic’s rapid transformation – a very rare convergence of almost every national priority in the most rapidly-changing region on the face of the Earth”. It is good to see climate and environment get a mention at least.

A “Stern” warning

The Guardian had a guest article by Nicholas Stern, the author of that famous Stern Report on the economics of climate change back in 2006 (yes, it really is that long ago).The background to this, of course, is the wild weather in the UK. Now I do not wish that kind of weather on anyone, but in terms of drawing attention to climate change it has certainly been very important. Stern writes “The record rainfall and storm surges that have brought flooding across the UK are a clear sign that we are already experiencing the impacts of climate change”. He makes a clear case for linking the two. He also brings in the other extreme weather around the globe, including Australia, Argentina and Brazil and the devastating typhoon Haiyan in the Philippines last year. Stern has clear advice for the politicians:

“This is a pattern of global change that it would be very unwise to ignore.” Stern says the risks are even bigger than when he wrote the 2006 report. “Since then, annual greenhaouse gas emissions have increased steeply and some of the impacts, such as the decline of Arctic sea ice, have started to happen much more quickly.”

I hope a lot of decision-makers and influential business people have read or will still read Stern’s article. He calls for rapid action and investment. He has a clear message for the European Union, currently not the most popular international organisation with the British government. “The UK whould work with the rest of the EU to create a unified and much better functioning energy market and power grid structure. ‘this would also increase energy security, lower costs and reduce emissions. What better was is there to bring Europe together?” Other measures recommended would be to implement a “strong price on greenhouse gas pollution across the economy”. This, remember, is a renowned economist, not an environmental campaigner. He also warns against the temptation to cut overseas aid to fund adaptation to climate change. “It would be deeply immoral to penalise the 1.2 billion people around the world who libve in extreme poverty…In fact, the UK should be increasing aid to poor countries to help them develop economically in a climate that is becoming more hostile largely because of past emissions by rich countries”- Yes. Yes. Yes.

Don’t let the weather distract from your climate awareness!

The other piece of writing which inspired me over the weekend was in the ImaGeo blog by Tom Yulsman: “Move over polar vortex“. He looks at the new analysis produced by the UK’s Met Office:

“If a new scientific analysis is correct, the repeated bouts of extreme weather on either side of the Atlantic are indeed unusual – and both are manifestations of a chain of climatic teleconnections that reach half way around the globe and all the way to the tropics”.

There is a lot of talk in this piece of whether the polar vortex is weak (as discussed in my article More Arctic Weather in a Warming World?) Or actually “particularly intense”. I would recommend you read Tom’s blog for yourselves for the details and his views. But the insight I would leave you with here as “food for thought” is where he quotes a paper in the journal Science.

“They conclude that the recent discourse focusing on the possible connections between winter weather and climate change distracts from the bigger issue: that is, regardless of extreme winter weather, climate change is undoubtedly real, and that harsh winters are not what we really need to be concerned about going forward as the climate continues to change”.

People love to talk about the weather. But if we use every instance of unusual weather to question the overall trend of global warming, with all the complex effects that has on our climate, winds, oceans etc, we run the risk of losing a necessary sense of urgency when it comes to reducing emissions. I am reminded, as I often am, of a young climate ambassador from the Netherlands during a fact-finding trip to Alaska in 2008. As we stood at the Visitor’s Centre for a glacier which is now no longer visible from that spot because it has retreated so far, he said that just brought home to him how “everything is connected”. Our everyday lifestyle in the industrialised world is melting the Arctic ice – and that, in turn, is contributing to the changing climate patterns which can radically alter the planet.

Climate Change: Arctic in denial?

If there is one place you would imagine people would have to be conscious of climate change, it would be the Arctic, where the temperature is rising around twice as fast as the global average. As I mentioned in the Ice Blog yesterday and in my article on dw.de from here in Tromsö, changes to the sea ice and temperature are altering life rapidly and visibly for people in the high north. So I was intrigued by a side-event here at Arctic Frontiers, which made it clear that this does not necessarily mean people are aware of climate change and what it involves – at least not consciously or actively.

“How to Create a Climate for Change” was the subject of the workshop organised by UArctic, the University of the Arctic. (That is not the same as Tromsö University, which is called Norway’s Arctic University. UArctic is a cooperative network of northern universities and other educational institutions.)

The workshop was looking at awareness of climate change in Norway and other Arctic regions. Kari Marie Norgaard is Professor of Sociology at the University of Oregon in the USA. She spent ten months researching in Bygdaby,a community in northern Norway and told us she had actually monitored an “incredible disconnect between the moral, social, and environmental crisis of climate change and people not realising it is happening.”

This is not limited to the Arctic, although it seems particularly striking in an area undergoing such major changes. There seems to be a widespread paradox in that climate change is leading to dramatic alterations to ecology systems and significant social consequences, but that there is no widespread sense of a need for urgent action.

This is not limited to the Arctic, although it seems particularly striking in an area undergoing such major changes. There seems to be a widespread paradox in that climate change is leading to dramatic alterations to ecology systems and significant social consequences, but that there is no widespread sense of a need for urgent action. Humans, says Norgaard, are “not getting it”. They are carrying on regardless, acting as if nothing were happening.

Denial but not climate scepticism

She speaks of “denial”, but not in the sense that people do not accept that climate change is happening. Norgaard told me she has come under a lot of pressure from the extreme right in the USA, who do not understand her distinction. Her hypothesis is that we know climate change is happening just as we know violence, rape or massacres happen. But we do not perceive it as psychologically disturbing or carrying a moral imperative to act. Norgaard is interested in how and why people collectively resist information about climate change. She focuses on Norway rather than her home country USA because this is a country with a high rate of newspaper readership, high levels of political participation,and where climate change is more visible in the northern region, and people know it is happening.

But in spite of the fact that Bygdaby is highly dependent on farming and tourism, where the climate is important, the fact that the winter had been warm, the snow was two months late and artificial snow had to be used for skiing, did not result in a heightened interest in climate change. In fact, she says, it was invisible in social or political life. One of her conclusions is that people want to protect themselves to some extent and so prefer to live as if climate change was not happening. Her theory is that people don’t want to feel guilty about their lifestyle and also try to avoid fear of the future and feeling helpless.

The greatest communication failure of all time?

Althouth Norgaard did her research in Norway, she says the findings apply equally elsewhere, including the USA, where regions are already experiencing climate impacts with economic consequences, but people don’t want to accept that it could have something to do with their lifestyle and require unpleasant action.

Per Espen Stoknes is Associate Professor at the Center for Climate Strategy of the Norwegian Business Institute NBI. He says surveys going back to 1989 in Norway show a decrease in people’s concern about the greenhouse effect and climate change .Only

4 in 10 see it as a problem and only 8% see it as being of importance. Espen stresses this is not because of a lack of knowledge. In fact, he thinks the better the facts get, the less people care.

Stoknes came up with an interesting figure. Apparently the public has the impression only 55% of climate scientists agree on global warming. In realty, it is 97%.Getting the message about climate change across is the ““Greatest communication failure of all time”, says Stoknes.

Who’s to blame?

Some of the responsibility lies with the scientists in his view. He says scientists need to lecture people less and discuss more. Another problem is that people tend to think of climate as being very distant in time and space. An IPCC estimate for 2100 seems a long way away. For people outside the Arctic, melting sea ice also seems geographically very remote. The same applies to places like Bangladesh or the Maldives.

Stoknes suggestions for improving the situation are not new. But evidently, the message has not got across – or the suggestions proved not effective. He says the media should have less gloom and doom and present more positive stories and examples of practicable action. If only it were that simple.

I remember numerous heated discussions on this topic at a Global Media Forum on Climate Change and the Media in Bonn in 2010, and atvarious other events I was involved in. Communicating climate change in a way that will make people take action in their everyday lives and put pressure on governments to do the same, remains a priority and a challenge.

One idea Stoknes has strikes me as being useful. He stresses the power of social norms to change behaviour, and suggests campaigns that make people compete with their peers – neighbours, other towns, friends, relatives, for being climate-conscious, can be effective. He talked about the success of an app where people can record and compare their energy saving.

Another possibility is to make “greener” options the default, something I was talking further about with some US colleagues today. If the normal way a printer works is to use both sides of the paper, for instance, people will do that. Not though if they have to change a setting

Plenty of food for thought here. The psychological and social dimensions of climate change awareness clearly deserve more consideration.

![6418.3[1]](http://blogs.dw.com/ice/files/6418.31.jpg)

Feedback