How adaptable are Arctic ecosystems?

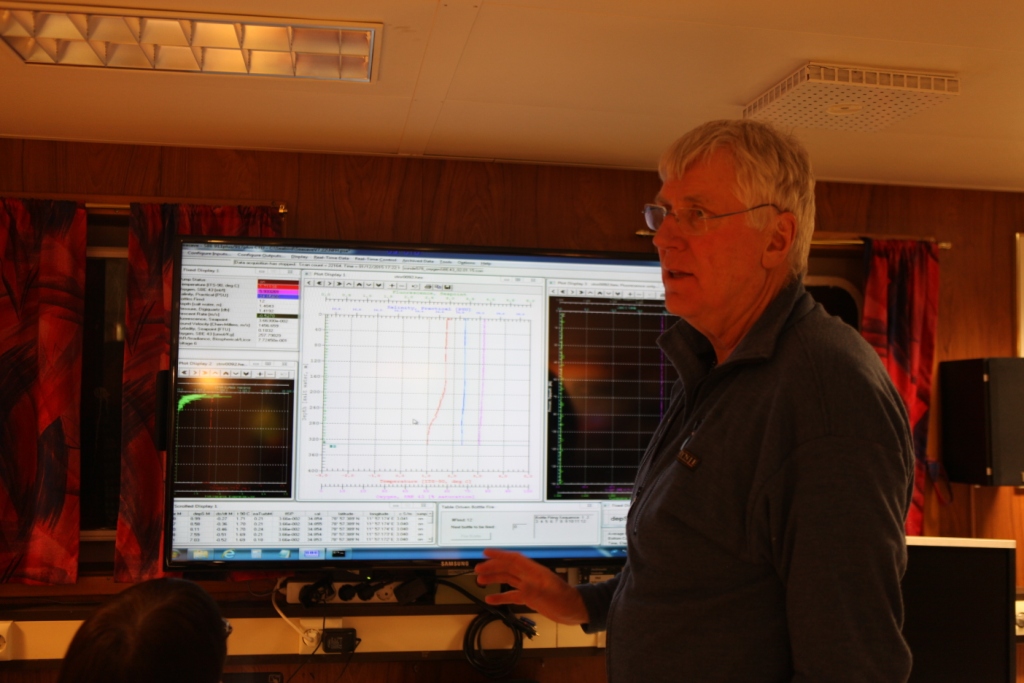

The man in charge of this scientific cruise is Stig Falk-Petersen, Professor at the Arctic University of Norway in Tromso and research advisor at Akvaplan-niva, a research consultancy working on environment monitoring. Originally from the Lofoten islands, he is a fountain of knowledge on marine life but also on history, especially relating to changes in the Arctic and indeed the European climate in general. He makes climate history of warm and cold periods more understandable by relating it to events like the Napoleonic wars, or the battle of Stalingrad. He stresses how that kind of approach shows just how important the climate is to society. He also knows a lot about the history of Arctic research. We owe a lot to Russia, where most of the Arctic research came from for a long time, says Stig.

Filling the winter gaps

I had a long talk with him, getting the background to this whole Polar Night project, which started in 2012. Apart from Nansen’s famous ice drift with the Fram (currently being repeated, but that’s a story for later), and the Russian North Pole drift stations, there had been few expeditions to the Arctic ocean in winter. Especially with regard to the southern part of the Arctic Ocean and the Fram strait, there were (and still are) huge gaps in our knowledge, Stig told me. In 2012 conditions were right for winter expeditions to the north and north west of Svalbard, to study the ecosystems. This was to complement a set of permanent observatories set up in the fjords here, measuring temperature, salinity, oxygen, light, chlorophyll and the movement of plankton.

Easier access through climate change?

I wanted to know why this has become possible. Is it because of climate change? Stig told me we actually have a climate record from 1550 until today about the ice around Spitsbergen, going back to accounts of Dutch whalers, which cover around 150 years, then to British expeditions. Since 1979 we have satellite records. All of this shows a large variation in the ice cover. Around 1680, he says, the whole of Spitsbergen was actually ice free. This lasted until 1800, when the ice expanded again from 82 degrees north to 76 degrees north – a huge and fast expansion of the ice cap. Then all this area was ice cold until approximately 1939. Since the year 2000, the region where we are now has been open again. “So you have this large variation of ice cover, driven by various climate factors, – temperature, pressure system, and that means a dramatic change for animals living in this area”, says Stig. To him, this shows the ecosystem up here is able to adapt to considerable change.

Ice, less ice, no ice?

“If you look back 50 years, this was all ice covered, so there was no primary production, so there were very few of these marine animals. Now, since the ice has retreated, the year 2000 approximately, we have a huge bloom of phytoplankton in the spring. So we have nutrients there, and we see that the calumus species, which is important for whales, is there. The bowhead whale, which was more or less extinct in this region for 150 years, is now back”. So, clearly, there are some winners – at least temporarily – in the course of climate change..

Our expedition leader was involved in one research project which could indicate that even some ice- dependent creatures have their own ways of coping with ice-free spells. He and his colleagues found that some tiny creatures which eat off the ice algae under the ice, float out with the ice. When it melts in summer in the Fram Strait, the egg-carrying females migrate down into the North Atlantic current, which then flows up into the Arctic Ocean, then migrate upwards in the water again. “Exactly when the ice algae blooms, in March April, their offspring is back and feeding again,” says Stig. So does that indicate that ecosystems here in the Arctic are well able to adapt to large variations in the climate, I want to know. Stig is reluctant to make anything that could be interpreted as a prediction of what future climate change could hold in store for the High North. But he stresses the temperature has increased in the Arctic by 2 degrees since 1987, much higher than the global increase. His impression is that the ecosystem has adapted well even to such a huge change in a short period. He doesn’t see himself as an optimist. But this view is certainly more optimistic than a lot of other people I talk to about the Arctic.