Search Results for Tag: Greenland

Arctic future: not so permafrost

“A glance into the future of the Arctic” was the title of a press release I received from the Alfred Wegener Institute this week, relating to the permafrost landscape.

“Thawing ice wedges substantially change the permafrost landscape” was the sub-title.

“I felt the earth move under my feet…” was the song line that came to my mind.

The study was led by Anna Liljedahl of the University of Alaska in Fairbanks. And Fairbanks is, indeed, where I would like to have been this past week, with Arctic Science Summit Week taking place.

Arctic Council in Fairbanks

Clearly the Arctic Council thought the same and actually managed to put their wish into practice by holding a meeting of the Senior Arctic Officials (SAOs) there from March 15th to 17th. The agenda focused to a large extent, it seems, on climate change, and “placing the Council’s overall work on climate change in the context of the COP21 climate agreement” reached in Paris in December, according to a media release.

“The Council needs to consider how it can continue to evolve to meet the new challenges of the Arctic, particularly in light of the Paris Agreement on climate change. We took some steps in that direction this week”, said Ambassador David Balton, Chair of the SAOs.

Now what exactly does that mean? The Working Groups reported “progress on specific elements”. They include the release of a new report on the Arctic freshwater system in a changing climate, “cross-cutting efforts aimed at preventing the introduction of invasive alien species”, strengthening the region’s search and rescue capacity, efforts to support a pan-Arctic network of marine protected areas and promoting “community-based Arctic leadership on renewable energy microgrids”. I suppose those could be part of the process. Clearly there are a lot of interesting things going on.

NOAA’S latest – not so cheery

Against the background of NOAA’s latest revelations on global temperature development, though, they may have to speed up the pace. The combined average temperature over global land and ocean surfaces for February 2016 was the highest for February in the 137-year period of record, NOAA reports, at 1.21°C (2.18°F) above the 20th century average of 12.1°C (53.9°F). This was not only the highest for February in the 1880–2016 record—surpassing the previous record set in 2015 by 0.33°C / 0.59°F—but it surpassed the all-time monthly record set just two months ago in December 2015 by 0.09°C (0.16°F).

Overall, the six highest monthly temperature departures in the record have all occurred in the past six months. February 2016 also marks the 10th consecutive month a monthly global temperature record has been broken. The average global temperature across land surfaces was 2.31°C (4.16°F) above the 20th century average of 3.2°C (37.8°F), the highest February temperature on record, surpassing the previous records set in 1998 and 2015 by 0.63°C (1.13°F) and surpassing the all-time single-month record set in March 2008 by 0.43°C (0.77°).

Here in Germany, the temperature was 3.0°C (5.4°F) above the 1961–1990 average for February. NOAA attributes it to a large extent to strong west and southwest winds. Now that is a big difference, and I can certainly see it in nature all around. But the difference was more than double that in Alaska. Alaska reported its warmest February in its 92-year period of record, at 6.9°C (12.4°F) higher than the 20th century average.

Why worry about wedges?

So, back to Fairbanks, or at least to the changing permafrost in this rapidly warming climate, which was on the agenda there at the Arctic Science Summit Week. (See webcast.)

The study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, conducted by an international team in cooperation with the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Center for Polar and Marine Research (no wonder we prefer to call them AWI), indicates that ice wedges in permafrost throughout the Arctic are thawing at a rapid pace. The first thought that springs to my mind is collapsing buildings, remembering seeing cooling systems in Greenland to keep the foundations of buildings in the permafrost frozen and so stable. Of course that only affects areas which are built upon (certainly bad enough). The new study looks at what the melting ice wedges will mean for the hydrology of the Arctic tundra. And that impact will be massive, the scientists say.

The ice wedges go down as far as 40 metres into the ground and have formed over hundreds or even thousands of years, through freezing and melting processes. Now the researchers have found that even very brief periods of above-average temperatures can cause rapid changes to ice wedges in the permafrost near the surface. In nine out of the ten areas studied, they found that ice wedges thawed near the surface, and that the ground subsided as a result. So, once more, humankind is changing what nature created over thousands of years in a very short space of time. I am reminded of a recent study indicating that our greenhouse gas emissions have even postponed the next ice age.

A dry future for the Arctic?

“The subsiding of the ground changes the ground’s water flow pattern and thus the entire water balance”, says Julia Boike from AWI, who was involved in the study. “In particular, runoff increases, which means that water from the snowmelt in the spring, for example, is not absorbed by small polygon ponds in the tundra but rather is rapidly flowing towards streams and larger rivers via the newly developing hydrological networks along thawing ice wedges”. The experts produced models which suggest the Arctic will lose many of its lakes and wetland areas if the permafrost retreats.

Co-author Guido Grosse, also from AWI, says the thaw is much more significant that it might first appear. The changes to the flow pattern also change the biochemical processes which depend on ground moisture saturation, he says.

The permafrost contains huge amounts of frozen carbon from dead plant matter. When the temperature rises and the permafrost thaws, microorganisms become active and break down the previously trapped carbon. This in turn produces the greenhouse gases methane and carbon dioxide. This is a topic already well researched, at least with regard to slow and steady temperature rises and thawing of near-surface permafrost, the authors say. But the thawing of these deep ice wedges will lead to massive local changes in patterns. “The future carbon balance in the permafrost regions depends on whether it will get wetter or dryer. While we are able to predict rainfall and temperature, the moisture state of the land surface and the way the microbes decompose the soil carbon also depends on how much water drains off”, says Julia Boike.

Now the results of the research have to be integrated into large-scale models.

The study of the impacts of thawing ice wedges seems to me like a good metaphor for the relation between Arctic climate change and what’s happening to the planet as a whole. Something changes in a localised area, which turns out to have far greater significance for a much wider area of the planet (or even the whole).

Rising seas culprit: ice or heat?

My attention was caught this week by a study that ascertained that thermal expansion accounts for a much greater share of sea level rise than previously thought. In fact, quite a few journalists got the message wrong. They thought the researchers had found that climate change was causing sea level rise twice as high as previously thought, which would have been quite a sensation. In fact, what the scientists actually found was that the amount of sea level rise that comes from the oceans warming and expanding has been underestimated and is probably about twice as much as previously calculated. There is a clear difference, which does not make the research – using the latest available satellite data – any less interesting.

Since two of the authors of the study are based here in Bonn, I was able to drop in on them and get them to explain their findings and the implications for our Living Planet programme. That will be broadcast in the near future. I also talked to Professor Anders Levermann from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research on the phone, to get the research findings into context.

While physicists understand the workings of thermal expansion in the oceans in general, Levermann told me there is still a lot to learn about how the heat from excess warming is transported in the ocean, which is of key importance to understanding sea level rise, amongst other things. He says the new research will help make models of future sea level rise more accurate.

The Bonn researchers explained to me how satellite technology has made huge improvements in the collection of data, especially relating to the very deep areas of the ocean, which are very difficult to reach with conventional measuring gauges. Professor Kusche told me he would like to see the results of the study, published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, being used by governments and coastal planners, as sea level rise will affect a large number of people living in coastal areas in the not-too-distant future. Warming seas are also linked to the occurence of storms, making the findings doubly relevant to those involved in protecting coastal areas.

From an Iceblogger point of view, I was keen to know whether the knowledge about the amount of sea level rise ascribed to thermal expansion had any implications for the role played by melting ice in raising sea level. If thermal expansion is accounting for a higher share of the sea level rise, is melting ice from Greenland and Antarctica accounting for less? I put that question first to Professor Kusche.

“We think that less of the sea level rise is coming from melting ice and glaciers, that’s actually true,” he answered. He said he and his colleagues had done a very thorough re-analysis of all the measurements available over the last 12 or 13 years, “and we are pretty sure that our numbers are correct”.

Rietbroek came in that that point: “Less, but not that much less. If you look at pubished literature and estimates of glacier melting, and try to add those up, you won’t be that far away from what we get. So the melting of glaciers is not that different from what’s been found previously”, he added.

I put the same question to Professor Levermann from PIK, who runs an ice sheet model for the Antarctic and was lead author of the IPCC chapter on sea level change. He explained to me that the various contributions to sea level rise are measured and modelled separately by different teams of experts in particular fields. The models all have a wide range of possible variation. He told me there is still some uncertainty in the distribution of the “sea level rise budget” between thermal expansion, ice sheet melt, mountain glacier melt and groundwater mining. While the latest findings on thermal expansion could potentially shift the relative contributions and are important for improving models to project future sea level rise more accurately, they do not change the validity of predictions relating to the amount of ice going into the ocean.

Ultimately, Levermann says, one of the IPCC statements with the highest certainty is that sea level will continue to rise for centuries to come. He was one of the authors of yet another study published in Nature Climate Change this past week, led by Peter Clark from the Oregon State University. It affirms that our greenhouse gas emissions today produce climate change commitments for many centuries to millenia. Unless the Paris climate agreement is put into practice asap and we reach zero or negative emissions, up to 20 percent of the world’s population will find itself living in areas that may have to be abandoned.

We are, indeed, living in the Anthropocene. Recently, I interviewed a scientist who found that we have already postponed the next ice age by 50,000 years through our fossil fuel emissions. The latest sea level study indicates that the next few decades offer a brief window of opportunity to avoid increased ice loss from Antarctica and “large-scale and potentially catastrophic climate change that will extend longer than the entire history of human civilization thus far”.

Record permafrost erosion in Alaska bodes ill for Arctic infrastructure

At Point Barrow, the northernmost point in the USA, a whole village was lost to erosion (Pic: I.Quaile)

Sitting in my office on the banks of the river Rhine, I am trying to imagine what would happen if the fast-flowing river was eating into the river bank at an average rate of 19 metres per year. It would not belong before our broadcasting headquarters, the UN campus tower and the multi-story Posttower building collapsed, with devastating consequences.

Fortunately, Bonn is not built on permafrost, so we don’t have that particular concern.

Record erosion on riverbank

The record erosion German scientists have been measuring in Alaska probably hasn’t been making the headlines because it is happening in a very sparsely populated area, where no homes or important structures are endangered.

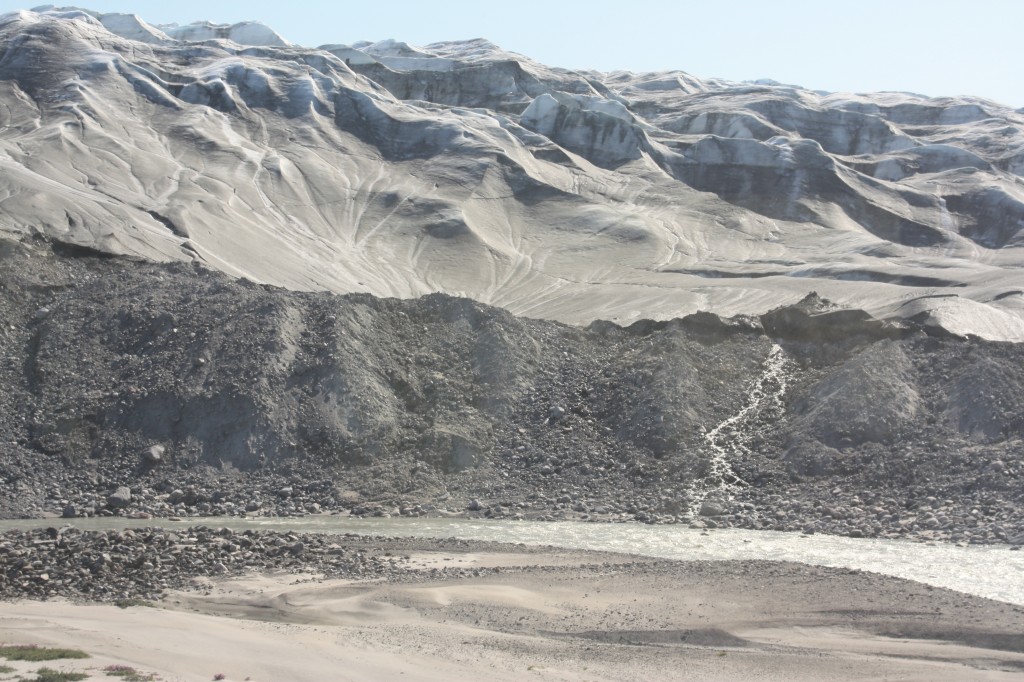

Nevertheless, it certainly provides plenty of food for thought, says permafrost scientist Jens Strauss from the Potsdam-based research unit of the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI). He and an international team have measured riverbank, erosion rates which exceed all previous records along the Itkillik River in northern Alaska. In a study published in the journal Geomorphology, the researchers report that the river is eating into the bank at 19 metres per year in a stretch of land where the ground contains a particularly large quantity of ice.

“These results demonstrate that permafrost thawing is not exclusively a slow process, but that its consequences can be felt immediately”, says Strauss.

With colleagues from the USA, Canada and Russia, he investigated the river at a point where it cuts through a plateau, where the sub-surface consists to 80 percent of pure ice and to 20 percent of frozen sediment. In the past, the ground ice, which is between 13,000 and 50,000 years old, stabilized the riverbank zone. The scientists, who have been observing the location for several years, demonstrated that the stabilization mechanisms fail if two factors coincide. That happens when the river carries flowing water over an extended period, and where the riverbank consists of steep cliff, which has a front facing south, and is thus exposed to a lot of direct sunlight.

Minus 12C average no safeguard

The warmer water thaws the permafrost and transports the falling material away, and in spite of a mean annual temperature of minus twelve degrees Celsius, summer sunlight makes it warm enough to send lumps of ice and mud flowing down the slope, according to Michail Kanevskixy from the University of Alaska Fairbanks, lead author of the study.

Overall, between 2007 and 2011, the cliff – which is 700 metres long and 35 metres high – retreated up to 100 metres, resulting in the loss of 31,000 square metres of land area. That is a large area, around 4.3 football fields, the scientists calculate.

In August 2007, they also witnessed how fissures formed within a few days, up to 100 metres long and 13 metres deep.

“Such failures follow a defined pattern”, says Jens Strauss. “First, the river begins to thaw the cliff and scours an overhang at the base. From here, fissures form in the soil following the large ice columns. The block then disconnects from the cliff, piece by piece, and collapses”.

Infrastructure under threat

Although these spectacular events happened far from populated areas and infrastructure, the magnitude of the erosion gives cause for much concern, given the rate at which temperatures are increasing in the Arctic. The scientists want their information to be used in the planning of new settlements, power routes and transport links. They also stress that the erosion impairs water quality on the rivers, which are often used for drinking water.

But what about those areas of the High North where there are settlements and key infrastructure? Russia is starting to get very worried about the effects of increasing permafrost erosion.

Last month the country’s Minister of Natural Resources, Sergey Donsjkoy, expressed grave concern. The Independent Barents Observer quoted the Minister as saying, in an interview with RIA Novosti, he feared the thawing permafrost would undermine the stability of Arctic infrastructure and increase the likelihood of dangerous phenomena like sinkholes. Russia has important oil and gas installations in Arctic regions. Clearly, any damage would have considerable economic implications. There are also whole cities built on permafrost in the Russian north.

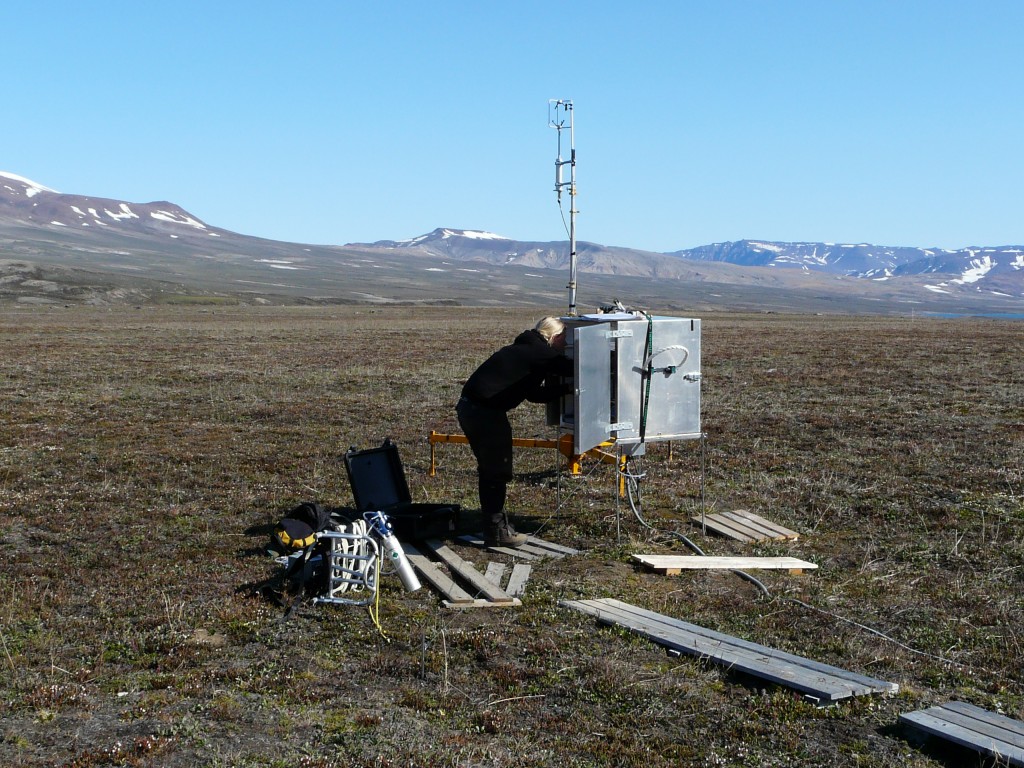

System to cool the foundations of a building on permafrost in Kangerlussuaq, Greenland (pic: I.Quaile)

High time to adapt

In 2014, I interviewed Hugues Lantuit, a coastal permafrost geomorphologist with the Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research, about an integrated database on permafrost temperature being set up as an EU project. He told me it would be very hard to halt this permafrost thaw, and stressed that permafrost underlies 44 percent of the land part of the northern hemisphere.

“The air temperature is warming in the Arctic, and we need to build and adapt infrastructure to these changing conditions. It’s very hard, because permafrost is frozen ground. It contains ice, and sometimes this ice is not distributed evenly under the surface. It’s very hard to predict where it’s going to be, and thus where the impact will be as the permafrost warms and thaws”.

I remember being shocked to see that people in Greenland were having to use refrigeration to keep the foundations of their buildings on permafrost stable. The scale of the problem is clearly much greater in cities like Yakutsk.

Then, of course comes the feedback problem, when thawing permafrost releases the organic carbon stored within it. Let me give the last word to Hugues Lantuit:

“This is a major issue, because it contains a lot of what we call organic carbon, and that is stored in the upper part of permafrost. And if that warms, the carbon is made available to microorganisms that convert it back to carbon dioxide and methane. And we estimate right now that there is twice as much organic carbon in permafrost as there is in the atmosphere. So you can see the scale of the potential impact of warming in the Arctic.”

Anthropocene: No ice age – more blizzards?

If you are sitting somewhere on the East Coast of the USA, struggling to cope with 30 inches of snow, you might be forgiven for reacting with relief to a report released by the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) indicating human-made climate change is suppressing the next ice age. With a wink in your eye, you might be very grateful that these extreme conditions are only going to last for a few days and not become the everyday normality of a new ice age.

There are those (but increasingly few of them) who might even thank the fossil fuels industries for averting a scenario like “The Day after Tomorrow” and ensuring that the relatively comfortable interglacial in which we live is likely to continue for the next 100,000 years. That is the conclusion of the study published in the scientific journal Nature.

The problem is that postponing an ice-age illustrates that human interference with natural climate cycles over a relatively short time has the potential to change the world for a hundred thousand years to come, with all the problems that come with it. And given that the increase in extreme weather events like the US snowstorm is highly probably related to anthropogenic climate change, perhaps an ice age in 50,000 years would be the lesser evil.

Burn fossil fuels, suppress the ice age

Using complex models to try to find out which factors influenced the last eight glacial cycles in earth history and what is likely to lie ahead of us, the scientists found that as well as astronomical factors like the earth’s position in relation to the sun in different stages of its orbit, the CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is a key factor.

I talked to physicist and earth systems modeler Andrey Ganopolski, lead author of the study to find out more about the research and the background.

According to Milankovich’s theory, a new ice age should occur when the earth is far away from the sun and summer is colder than usual in the northern hemisphere, at high latitudes in Canada and northern Europe. These are the areas where big ice sheets can grow. At the moment, Ganopolski explained, we have a situation where our summer occurs when the earth is far from the sun. So in principle, we have the conditions when a new ice age can potentially start. He and his colleagues wanted to understand why we are not living in an ice age when astronomically, the conditions are just right to move towards a new ice age.

Meddling with the planet

They come to the conclusion that naturally, without any anthropogenic influence, we would expect the new ice age to start around 50,000 years from now. That would mean that this interglacial, the Holocene, in which we live now, would already be unusually long. In the past, an interglacial lasted only 10 or 20,000 years, but this one is expected to last for 60,000 years.

But our emissions of greenhouse gases are postponing this even further. Relatively large anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions – say two to three times what we already emitted – would, according to the scientists’ model, additionally postpone the next ice age, so that it would only start 100, 000 years from now, so we would completely skip one glacial cycle, which never happened in the last three million years.

Humankind as a geological force

Now regardless of whether you are a fan of ice and snow or one of those who say they can happily live without any more ice ages, the study’s findings illustrate just how long anthropogenic influence on climate will continue. Humanity, it seems, has become a geological force that is able to suppress the beginning of the next ice age, according to the PIK experts. Human behavior is changing the natural cycles that have shaped the global environment and human evolution.

Over the last 3 million years, glacial cycles were more or less regular. Most of the evolution of humans occurred during those last three million years. Ganopolski says humans can be seen as a kind of product of glacial cycles, because the conditions were probably right to increase the size of our brain, because we had to be clever to survive in such a variable climate.

Who cares?

But given that it is easier and pleasanter to live in non ice-age conditions, there is still an understandable tendency to respond to the ice-age-postponement announcement with: “so what?”

Ganopolski argues one reason the study is significant is that it does away with the arguments of some climate skeptics who have argued that warming the atmosphere by burning fossil fuels is not a bad thing, because it could avert an “imminent” ice age (a theory first made popular around thirty years ago, he says). Since the research indicates there is none on the horizon for more than 50,000 years anyway, this is nonsense, says Ganopolski.

But the main reason the research findings deserve attention, he says, is that they show we can affect the climate for up to a hundred thousand years. He believes a lot of people think if we stop using fossil fuels tomorrow or the day after, everything will be fine. In fact, anthropogenic carbon dioxide will stay in the atmosphere for an extremely long time. “That means we are affecting earth’s future on a geological time scale”, he says.

Whether the next ice age comes in 50,000 or 100,000 years may seem irrelevant to a lot of people, faced with the concerns of life today. But the effects of our warming the globe are already being felt and will have considerable implications well before that, Ganopolski reminds us. He says the new study just shows how massive our interference with the earth’s systems is, and backs up the need to take action now to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

Rising CO2 emissions are influencing glacial patterns (Measuring station on Svalbard, Pic. I. Quaile)

Greenland and Antarctic in the Anthropocene

He mentions the research also deals with Greenland and Antarctica:

“What we show is that even with the CO2 concentration we have already, we can expect that a substantial fraction of these ice sheets will melt. So obviously, in this respect, any further increase of CO2 will have even more negative effects”.

Sea level rise, ocean acidification, changing food supplies, floods, droughts…and, yes, even more of those extreme blizzards, fuelled, paradoxically, by warming seas…maybe there is more to this delaying the ice age business than first seemed.

So are we living in the “Anthropocene”, i.e. an era in which not nature but humankind is determining the shape of the world we live in now and for centuries to come? Ganopolski and his colleagues say yes. He stresses what we are doing to the climate and the speed at which it is happening represent unprecedented, substantial deviation from the natural course of things.

“So if you continue to emit a substantial amount of carbon dioxide, the Anthropocene will last for hundreds of thousands of years, before systems return to anything like “normal” conditions”, he says.

Another study published in Nature today provides further evidence that human intervention is responsible for the annual heat records that have been in the news so often recently they run the risk of losing their news value. Ganopolski’s PIK colleague Stefan Rahmstorf, one of the authors, says the heat records, with 13 of the last 15 years the warmest since records began, can no longer be explained by natural climate variation. But they can be explained by human-induced climate change.

But is there any point in making potentially uncomfortable changes to the way we live today if we have already changed the atmosphere so massively, for such a long time to come? Ganopolski stresses the extent and speed of the changes and impacts are no grounds for resignation:

“There is no justification for making the climate even warmer than it is. It is a matter of how much CO2 we will emit into the atmosphere. Basically, it will affect all generations, and if we care about them, we should stop using fossil fuel as soon as possible.”

Sounds sensible to me.

Cloudy skies speed up Greenland melt

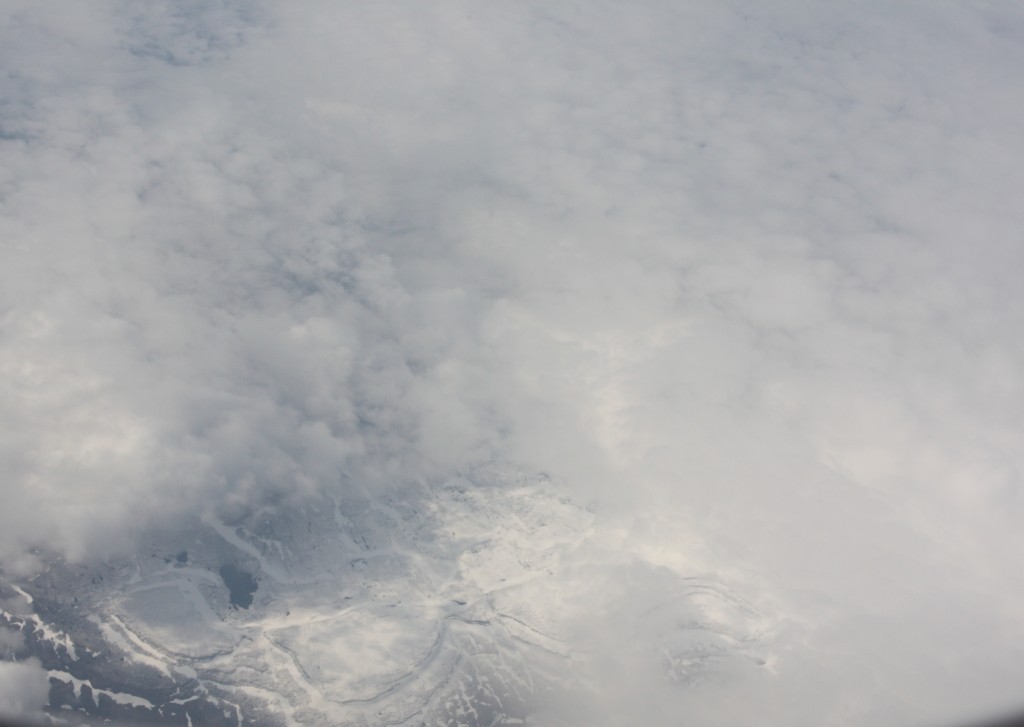

If the Greenland ice sheet were to melt completely, sea level could rise by 7 metres (pic: I.Quaile)

With Greenland known to be one of the main contributors to global sea level rise, mainly through increased meltwater runoff, it is hardly surprising that there is increasing and widespread scientific interest in finding out exactly what factors influence the melting and to what extent. Approximately half of Greenland’s current annual mass loss is attributed to runoff from surface melt.

In my last Ice Blog post, I looked at a study showing that recent atmospheric warming is reducing the ability of some layers of the Greenland ice sheet to store meltwater. That, in turn, can mean runoff is released into the ocean faster than previously assumed, rushing down a kind of icy chute.

Clouds as a night-time warmer

This week, a study led by the University of Leuven in Belgium was published in Nature Communications that suggests that clouds are playing a greater role in this whole process than previously thought. The study concludes that clouds could be enhancing meltwater runoff by about a third relative to clear skies. The scientists used a combination of satellite observations, ground observations, climate model data and snow model simulations.

The impact is not just because the radiative effect of the clouds directly increases surface melt, but because the clouds actually reduce meltwater refreezing at night. They trap heat like a kind of blanket.

Tristan L’Ecuyer, professor in the Department of Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences at the University of Wisconsin-Madison and co author of the study, is quoted on the phys. Org science website as saying we could be dealing with another foot of sea level rise around the world over the next 80 years. “Parts of Miami and New York City are less than two feet above sea level; another foot of sea level rise and suddenly you have water in the city”, he warns.

L’Ecuyer stresses that clouds are still not adequately accounted for in climate models. He also stresses that climate models have not kept pace with the rate of melting actually observed on the Greenland ice Sheet.

Viewing clouds from above

Improved satellite coverage is improving the situation. L’Eciyer is affiliated with the UW-Madison Space Science and Engineering Center, a pioneer institute in satellite meteorology. Within the last 10 years, NASA has launched two satellites which, L’Ecuyer says, have changed our view of what clouds look like around the planet. He used “X-ray images” of Greenland’s clouds taken by CloudSat and CALIPSP between 2007 and 2010 to determine the structure of clouds, how high they were in the atmosphere, their vertical thickness and whether they were composed of ice or liquid. The Belgian team combined this data with ground-based observations, snow model simulations and climate model data to map the net effect of clouds. This indicated that cloud cover prevents ice that melts in the daytime sunlight from refreezing at night. That, in turn, flows off as meltwater.

The lead author of the study, Kristof Van Tricht from the University of Leuven, who spent six weeks in Madison last year working with L’Ecuyer, uses the sponge image to describe the snowpack. “At night, clear skies make a large amount of meltwater in the sponge refreeze. When the sky is overcast, by contrast, the temperature remains too high and only some of the water refreezes. As a result, the sponge is saturated more quickly and excess meltwater drains away”.

Clouds can cool the earth’s surface by reflecting sunlight back into space. Or they can trap heat like a blanket. On Greenland, scientists agree that clouds primarily act to trap heat.

As with so many climate phenomena, clouds can both affect the climate, and be changed by it. While on the one hand cloud cover can lead to more warming and more meltwater, the resulting effect on the ice sheet can, in turn, affect the cloud cover itself.

The scientists hope studies like this one, making use of advanced satellite technology, can help make future climate models become more accurate by taking this into account. To date, different models disagree on how clouds affect the largest body of ice and so freshwater in the northern hemisphere.

Feedback