Search Results for Tag: wildlife

Arctic oil – still in the picture

Was it too good to be true? The euphoria over the US administration’s moves to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was dampened somewhat when, just two days later, it released a long-term plan for opening coastal waters to oil and gas exploration, including areas in the Arctic off Alaska. The plan excludes some important ecological and subsistence areas from potential drilling, but it still includes some Arctic areas, including parts of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

Margaret Williams, managing director of WWF US Arctic Programs, told Deutsche Welle, she welcomed in particular the decision to protect the biological hotspot of Hanna Shoal from risky offshore drilling. The Hanna Shoal is a key site for walruses and other animals.

But she stressed other areas of the US Arctic were still subject to oil exploration. The new program will not affect existing leases held by Shell in the Chukchi Sea. The company’s efforts have been the subject of controversy, not least since the grounding of the drill rig Kulluk.

Williams says the problem with the new proposal in general is that it “keeps drilling for oil in the US Arctic offshore in the picture”. With the US poised to take the helm of the Arctic Council, she called for protecting biodiversity to be a top priority for all Arctic nations.

Oil: valuable asset or liability?

It comes as no surprise that Alaskan state politicians and the oil industry promised to fight planned restrictions, saying they were harmful to the economy. But this brings us back to the question of whether the search for new oil in the Arctic makes any sense at all at a time when oil prices are at a record low and the USA is producing plentiful supplies of shale gas.

Bloomberg financial news group quotes financial experts as saying the world’s biggest oil producers do not have “bulletproof business models”, and cites financial cutbacks by BP, Chevrol and Shell:

“The price collapse hobbles a segment of the industry that had already been struggling with years of soaring construction costs, project delays, missed output targets and depressed returns from refining crude into fuels”, analyst Anish Kapadia told Bloomberg.

Climate paradox

Conservation groups stressed the need for a different focus, in the year when the USA has pledged to help create an effective new world climate agreement in Paris in November.

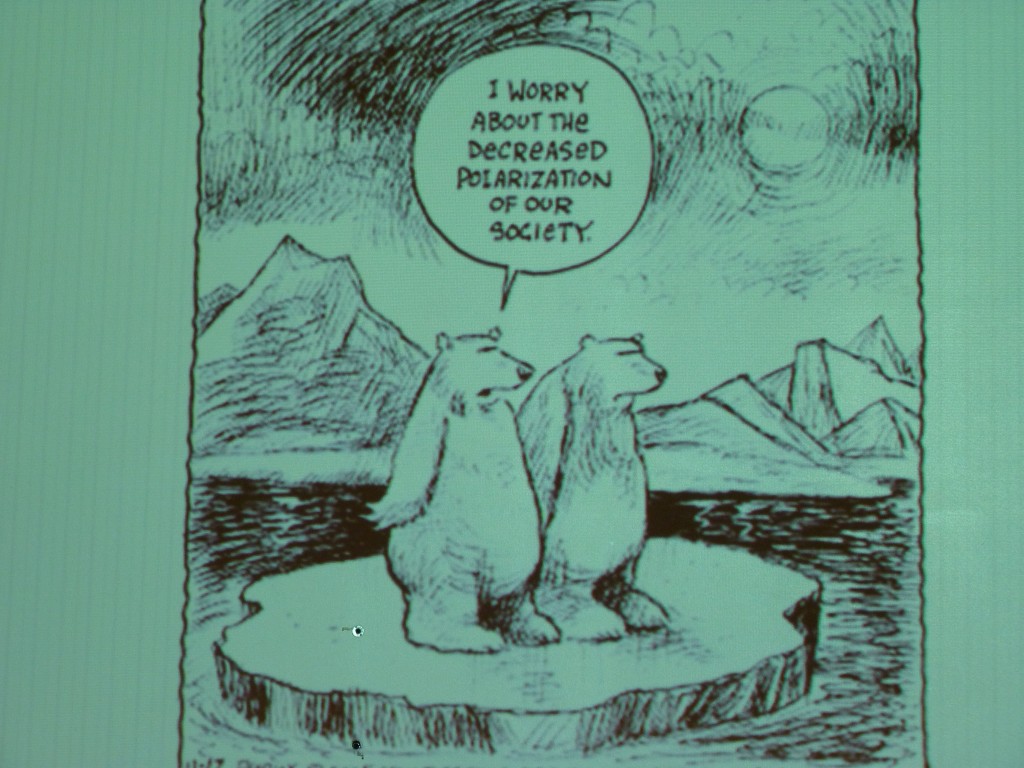

Cartoon by psychologist Per Espen Stoknes, BI Norwegian School of Management.( I photographed it at a workshop on climate change psyschology)

“Rather than opening more of the Arctic and other US coastal waters to drilling for dirty energy, the US needs to ramp-up its transition to a clean energy future. As the Administration works to rally international leaders behind a bold climate pact in 2015, decisions to tap new fossil fuel reserves off our own coasts sends mixed signals about US climate leadership abroad, ” said WWF’s Williams.

We know the Arctic is being hit at least twice as fast as the global average by climate change. The ecosystem is already under huge pressure. The Arctic itself is in turn of key importance to global weather patterns. And burning more oil would exacerbate the situation even further.

“We would like to think that we can shift our energy paradigm to clean energy so that we don’t have to take every last bit of oil out of the earth, especially out of the oceans”, said Jackie Savitz from the Oceana Campaign croup.

Studies by the group and by WWF indicate that developing renewable energy technologies such as offshore wind could create more jobs than hanging on to fossil fuel technologies.

Oil spill concern

In addition to the climate paradox of the hunt for new fossil fuels, environmentalists are concerned about the possible impact of an oil spill. Their opposition is not limited to the Arctic. Proposals to open up large areas of coastal waters including some parts of the Atlantic for the first time have also aroused anxiety about possible pollution. But the Arctic is of particular concern because of its remoteness, harsh weather conditions and seasonal ice cover, which is not likely to disappear soon even with rapid climate change:

“Encouraging further oil exploration in this harsh, unpredictable environment at a time when oil companies have no way of cleaning up spills threatens the health of our oceans and local communities they support. When the Deepwater Horizon spilled 210 million gallons of crude oil five years ago, local wildlife, communities and economies were decimated. We cannot allow that to happen in the Arctic or anywhere else,” said WWF expert Williams.

White House senior counsellor John Podesta justified the ban on oil exploration in the ANWR by saying “unfortunately accidents and spills can still happen, and the environmental impacts can sometimes be felt for many years”. The question is – why should this only be applicable in certain areas? Campaigners say it also applies to the other areas now designated by the administration as “OK” for exploration. For the Arctic in particular, limiting exploration to remote offshore areas does not protect the region against the risk of environmental disaster.

Obama stops oil in Arctic Wildlife Reserve

Back in Germany after spending a week and a half on the RV Helmer Hanssen off the coast of Spitsbergen, and then in Norway’s Arctic capital Tromso at Arctic Frontiers, I thought I might be in for a shock on my return to warmer climes and a news agenda focusing on stories non-Arctic. Instead, I found some continuity both in the weather and the media. A heavy fall of snow here kept the Arctic feeling alive, while a twitter of messages on Sunday carried on the lively debate that was happening at Arctic Frontiers over the pros and cons of oil drilling in the Arctic.

The Washington Post broke the story about President Obama proposing new wilderness protection in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). “Alaska Republicans declare war” was the second part of the headline. Clearly, emotions are running high.

The Obama administration is proposing setting aside more than 12 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska as wilderness. This stops – at least for the moment – any prospect of oil exploration in an area which has long been the subject of controversy between those who say environment protection should be the number one priority and those who say finding oil is more important.

“Alaska’s National Wildlife Refuge is an incredible place – pristine, undisturbed. It supports caribou and polar bears, all manner of marine life, countless species of birds and fish, and for centuries it supported many Alaska Native communities. But it’s very fragile”, the President says in a White House video about the proposals.

It seems this is only the first of a series of decisions to be made by the Interior Department relating to the state’s oil and gas production during the coming week. The Washington Post says the department will also put part of the Arctic Ocean off limits to drilling, and is considering whether to impose additional limits on oil and gas production in parts of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska.

Only the US Congress can actually create a wilderness area, but once the federal government has designated a place for that status, it receives the highest level of protection until Congress acts. “The move marks the latest instance of Obama’s aggressive use of executive authority to advance his top policy priorities”, writes Juliet Eilperin in the Washington Post.

The ANWR holds considerable reserves of petroleum, but is also a critical habitat for Arctic wildlife. Senator Lisa Murkowski from Alaska is the new chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Unsurprisingly, she is set to fight the Obama decision. The Governor of Alaska, Bill Walker, issued a statement saying he might have to accelerate giving permits for oil and gas on state lands to compensate for the new federal restrictions.

Can the fate of an area of such key ecological importance really be reduced to a good to be bargained for in a political tit-for-tat?

Conservation groups were over the moon about the Obama move. “Some places are simply too special to drill, and we are thrilled that a federal agency has acknowledged that the refuge merits wilderness protection”, said a statement from Jamie Williams, president of the Wilderness Society.

But apart from the danger of an oil spill and the threat to the habitat of Arctic species, we have to come back to that Tromso conference theme of Climate and Energy. The Arctic is being hit at least twice as fast as the global average by climate change. The ecosystem is already under huge pressure. The Arctic itself is of key importance to global weather patterns. And burning more oil would exacerbate the situation even further. I am reminded of the argument put forward by Jens Ulltveit-Moe, the CEO of Umoe, himself a former oil industry executive. Apart from the fact that the current low oil price means the Arctic oil hunt is too expensive, if the world is serious about emission cuts to halt climate warming, there is no need for and will be no demand for oil from the Arctic in coming decades.

That is something to be kept in mind as the debate in the USA continues over that precious piece of land and sea that is the ANWR.

Climate worry grows at Arctic Frontiers

I have followed the past two days, the political section of the Arctic Frontiers conference, with great interest, with the thought of the Paris climate conference in November always at the back of my mind.

Clearly, in a country rich from the sale of oil, cutting climate-killing emissions is a tricky issue. The oil sector was strongly represented here, but so too were those who see the need for a transition away from fossil fuels in the interests of the global climate.

With climate change opening the Arctic to development and the search for the oil, gas and minerals thought to be locked beneath the icy region, this year’s Arctic Frontiers meeting has attracted record participation. The impact of low oil prices on development prospects, and political tensions between Russia and western Arctic states have heightened interest in listening to what experts and decision-makers have to say on the relation between climate and energy.

Arctic fan Prince Albert of Monaco and US special rep Fran Ulmer debated the feasibility of Arctic oil

With prime ministers from Norway and Finland and other ministers from Sweden and Denmark, as well as the US special Representative for the Arctic and the Russian President’s special representative for international polar cooperation addressing the meeting, media interest is high in this Arctic city, two hours flight north of the Norwegian capital, Oslo. (Looking at my flight schedule, I see Oslo is actually closer to Frankfurt than to the Arctic north of the country).

Do we need Arctic oil in a warming world?

The Norwegian premier Erna Solberg was here for the presentation of a report on sustainable growth in the north, a joint venture by Norway, Sweden and Finland. Gas is one of the four drivers named in the report. She left no doubt about her country’s continuing interest in oil and gas exploitation in the Arctic region. She told me in a brief interview she sees no contradiction between this and attempts to reach a new world climate agreement in Paris at the end of the year:

“’We have an oil and gas strategy. There are many not yet found areas where we think there is more gas. We think gas is an important part of a future energy mix, and I think we have to explore to find it.”

The same day, the Norwegian government allocated new licenses for exploration in the north-western Barents sea area of the Arctic. Many of the blocks released for petroleum licensing are close to the sea ice zone that had previously been protected. The zones have now been redefined. Conservation groups are upset. WWF Norway says the announcement is risky, as there is still a lack of knowledge about species and ecosystems in this area.

Will low oil price halt Arctic energy development?

With oil prices at a record low, environmentalists hope Arctic development will slow down or even be put “on ice” permanently. Representatives of WWF told the delegates in Tromso – including high-ranking representatives of major oil companies Statoil and Rosneft – the world does not need oil from the Arctic. And gas should be only a “transition fuel”. Samantha Smith, leader of the ngo’s Global Climate and Energy Initiative, quoted the recent study indicating that 50% of the world’s remaining gas and 30% of the oil must stay in the ground if the two degrees centigrade target for maximum global temperature rise agreed by the international community is to have any chance of being adhered to. She presented an alternative vision of “a thriving green economy in the white north”, with renewable energies replacing the search for oil and gas.

Business rethinking fossil investment?

As I wrote here on the Ice Blog after the Sunday evening opening, it is not only the environment lobby that is advocating a switch to renewable enerergy. Jens Ulltveit-Moe, the CEO of Umoe, one of the largest, privately owned companies in Norway, active amongst other things in shipping and energy, said with the current low oil price, Arctic oil was simply not viable, and this would remain the case for many years to come. And by then, he said, the EU’s climate targets and the international support for a two-degree target would make fossil fuels a non-option.

But Sjell Giæver, Director of Petroarctic and Tim Dodson, Norwegian Statoil’s Head of Global Exploration, insisted short-term price drops alone would not halt Arctic exploration. The region was the last place to discover large new reservoirs to satisfy continuing high demand for oil and gas for an increasing world population.

Oil ventures in the Arctic have not been particularly successful in recent years. Statoil’s Dobson admits the biggest ever exploration drilling programme in the Barents Sea last year had a disappointing outcome. Statoil and others have also withdrawn from the hunt for oil off the coast of Greenland.

Russia hungry for Arctic energy

But the Russian President’s Special Representative for International Cooperation in the Arctic, Arthur Chilingarov, who is also a Member of the Board of Directors at the Russian oil giant Rosneft, stressed the company had completed construction of the northernmost well in the world last September. He said a new oil and gas field has been discovered and the program of Rosneft for 2015 to 2019 provided for a large volume of prospecting and drilling in the western part of the Arctic.

The rector of Tromso UiT Arctic University of Norway Anne Husbeckk and the mayor of Tromso Jens Johan Hyort have reason to be happy with the attendance at this year’s Arctic Frontiers event.

One factor however that is slowing Russian activity the Arctic is the implementation of sanctions by European countries and the USA on account of the tensions over Ukraine. Russia has turned to China and other countries for help, but the lack of western technology is an obstacle to further development in a region where bad weather, ice, remoteness and complete darkness in the winter months make oil and gas development a risky business.

There is a clear tendency amongst those involved in Arctic cooperation to play down the sanctions and keep political tensions out of the region. Norwegian President Solberg told me: “We have a good relationship in the Arctic Council with Russia. We have said we will be in line with Europe on sanctions, although Norway is one of the countries hit most by the counter-sanctions from Russia, for instance the fact that oil and gas exploration are among the sanction areas.”

But in the meantime, on a day-to-day basis, cooperation continues, for instance in the joint management of fish resources, said Solberg.

Business as usual?

While the debate continued in the political section of Arctic Frontiers, a new, business strand of the conference opened in parallel. It focuses – on oil, gas and minerals. Olav Orheim from GRID Arendal, a centre that works with UNEP, stressed that a lot of people here are in favour of Arctic oil and gas exploration, in the interests of jobs and economic benefits.Yet after the publication of last year’s IPCC report and with climate change high on the international agenda, there seems to be a wider acceptance here in Tromso of the disconnect between burning fossil fuels and the ever more urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Gunnar Sand is Vice President of SINTEF, the Norwegian “Foundation for Scientific and Industrial Research”, which has close ties to the oil business. From a moral point of view, “we all want to stay below the two degree limit”, says Sand. But it is not possible to change a society and an infrastructure based on fossil fuels overnight.

Technical progress too slow to stop warming

Technology for renewable energy is still not developing fast enough, says Sand. Emission reduction scenarios also rely heavily on carbon capture and storage (CCS), which would reduce emissions from fossil fuel burning and bridge the transition to a low-carbon economy. But the technology, which he himself has been involved in, is moving too slowly. I first met him during a visit to Svalbard, when he told me about a carbon capture and storage project, designed to capture emissions from Longyearbjen’s power station underground. He confirmed in Tromso that it has never been put into action.

Global warming, Sand says, is the most serious challenge of our time. This has to be reflected in political priorities. Governments have to create economic incentives to speed up change.

Salve Dahle, Chairman of the conference steering committee and master of ceremonies sporting a sealskin bow tie.

US special representative ex-Admiral Robert Papp indicated dealing with climate change would be one of the key policy drivers when the USA takes over the Chair of the Arctic Council, the international body that coordinates Arctic affairs, in April.

The Chair of the US Arctic Research Commission Fran Ulmer says a carbon tax would be the best way forward, to encourage industry and consumers to save energy and cut emissions. But she acknowledged the reluctance of governments to impose decisions that could upset their voters at the next election. That is the reality we face as countries weigh up their pledges for the November climate conference in Paris.

From Alaska to Ottawa

Ottawa has been the setting for “Arctic Change”, another major Arctic conference this week. It is organised by the research network ArcticNet. I was not able to attend, but have been interviewing various people for an article on DW about the meeting, and about what is happening in the Arctic at the moment. One of the people I spoke to was George Divoky, who went to the meeting to put his own work into context and get the “big picture” of how climate change is having an impact on the Arctic. George is the mainstay of Friends of Cooper Island

He has a bird research station on Cooper Island, off Barrow, Alaska. For 45 years, he has been there every summer, observing a colony of black guillemots, who breed there. As he told me when I first met him during a trip to Alaska in 2008, his ornithological observation widened out into an observation of climate change over the years, witnessing some dramatic changes. I would like to share his views with you here on the Ice Blog.

Iceblogger: Why are you attending the conference and what do you expect from it?

As someone who has spent the past 45 summers studying seabirds in the Alaskan Arctic, I am very interested in hearing the findings of arctic researchers working in other disciplines and geographic areas.

I expect to be brought up to date on the most recent findings of how warming and development is affecting the ecosystems and people of the Arctic. The information I obtain allows me to put my work (which is on a single species breeding on one island) in a much larger context.

Has the Canadian chairmanship of the Arctic Council affected Canada’s interest in the Arctic?

I know little of the international politics of the Arctic but my feeling is that Canada has always had a major interest in the Arctic because of the extent of their arctic lands and the large number of villages and settlements. With all that is now going on in the Arctic, Canada’s chairmanship certainly provides an opportunity for the country to focus on the region even more.

Are there differences in attitudes to the Arctic in the various countries involved? US; Canada, Russia, Norway…?

I feel that the US (with the exception of the indigenous people who live there) tends to treat its small part of the Arctic as a place to exploit natural resources and conduct research while Canadians have a much more organic (holistic) approach to the region. My impression is that is also true for Scandinavian countries.

What has been your experience of Arctic change on Cooper Island this year?

The 2014 breeding season on Cooper Island had the lowest number of breeding pairs of Black Guillemots in the last 20 years. Breeding success in 2014 was low as all of the younger siblings in then nests died from starvation during a major windstorm that occurred in August after ice retreat and parent birds could not find sufficient prey. We also had more polar bears on the island and interactions with them than during the last few years. Polar bears were rare visitors to the island until 2002.

What impacts of the above-average rise in temperature have you seen over your years on Cooper island?

Warming first aided the guillemots (1970s and 1980) as the summer snow-free period increased and was better suited for the 90 days it takes guillemots to breed. The size of the breeding colony increased during the initial stages of warming. Continued warming (1990s to present) caused the sea ice to rapidly retreat in July and August when guillemots are feeding nestlings and the loss of ice reduced the amount and quality of prey resulting in widespread starvation of nestlings. Reduced sea ice also forced polar bears to seek refuge on the island with large numbers of nestlings being eaten by bears.

How serious is the problem of thawing permafrost?

Thawing of permafrost has the potential to drastically change terrestrial ecosystems due to changes in drainage and plant communities. The large shorebird and waterfowl populations breeding on the tundra require large areas of ponds and lakes for breeding. Melting permafrost is allowing water to drain from the surface decreasing the extent of aquatic habitats while increasing the depth for root growth which facilitates shrubs replacing tundra plants.

Do you have a sense that there is a “rush for the Arctic’s resources” or is this just media hype?

It is clear to me that there is a rapidly increasing interest in arctic resources from government and industry.

Where should the priorities of Arctic research and Arctic policy be in coming years?

While there will certainly be increased research in the Arctic in coming years I think it is important to realize that just because humans know more about a region or ecosystem it does not necessarily follow that they will be any better at protecting it from impacts – or likely to do so. Pre-development ecological research is something most governments feel they must do to satisfy concerns about environmental degradation, but the ways in which that research can limit the effects of the post-development degradation – or assist in mitigating that degradation – is unclear. Similarly, researching climate change and its effects are important but of little practical use if the research does not inform government officials and result in policies that address the causes of climate change.

With the climate conference going on in Peru – do you have the feeling the world takes the changes in the Arctic seriously?

I feel that the entire issue of current and predicted climate change is now being taken more seriously and, as a result, there is more focus on what is occurring in the Arctic since people and government now see the changes in the Arctic as being less removed from their own experience.

Are you optimistic about the future of the Arctic?

I am not optimistic that what used to be considered the “Arctic” will persist into the future. The Arctic where I do research now bears little resemblance to the Arctic I first went to in 1970. With models showing summer sea ice may soon disappear and predictions for increasing temperatures and development, it is likely that current and future generations of researchers will also be taken aback with the pace of change during their time in the region. Clearly, the Arctic as a geographic region will persist but the characteristics that are evoked by the word “arctic” (i.e. snow and ice dominated landscapes far from human industrial development) will no longer apply to the region. And, of course, the biota adapted to the arctic ecosystems of the past will have very uncertain futures given the pace of change.

What will it look like in 20, 30, 50 years?

Much of the Arctic became technically subarctic during the last 20 years. At least for the near future, winters will always be cold in the Arctic so some seasonal snow and ice cover will be present but the annual period when snow and ice are present will decrease. The rate at which these changes will take place is unclear as an Arctic that is ice free in summer (and losing land ice in Greenland) might cause more rapid changes.

Can anything happen to save it?

I was very lucky to be able to be in the Arctic in the late 20th Century but it now seems clear that with the projected increases in atmospheric CO2 and resulting increases in temperatures and ocean acidifcation that the Arctic (as well as many of the earth’s natural areas) could be unrecognizable by the middle of the 21st Century.

Emperor Penguins in Distress

It has been a busy week for me here at DW, and unfortunately I was not able to do justice to the latest research on the likely fate of the Emperors down at the far south of the planet in the form of some interviews or a detailed article. Before I head off to a seminar tomorrow, I want to make sure the Ice Blog does not neglect our majestic friends in the Antarctic. Fortunately, Tim Radford from the Climate News Network has summed up the story: ” Loss of Antarctic sea ice through climate change threatens the emperor penguin’s habit to such an extent that scientists say it should now be made an iconic symbol – like China’s endangered giant panda – of the wildlife conservation movement” . Thanks Tim, Alex and all at the Climate News Network who keep us up-to-date on so many important climate issues. Thanks also to Dave Walsh for alerting to me to this study which, I am pleased to say, made its way into a lot of media outlets, if only briefly. Thanks also to Dave for the Belgian International Polar Foundation picture.

Allow me to quote at length from Tim’s summary:

“Global warming will this century take its toll of Antarctica’s most regal predator, the emperor penguin. There are now 45 colonies of this wonderful bird, but by 2100 the populations of two-thirds of these colonies will have fallen by half or more.

Stéphanie Jenouvrier, a biologist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institution in the US, and colleagues from France and the Netherlands report in Nature Climate Change that changes in the extent and thickness of sea ice will create serious problems for a flightless, streamlined , survival machine that can live and even breed at minus 40°C, trek across 120 kilometres of ice, and dive to depths of more than 500 metres. The researchers took all the data from 50 years of intensive observation of one colony in Terre Adélie and used climate models to project a future for the other 44 colonies known in the Antarctic.

Decisive factor

They found that the decisive factor in emperor penguin survival was the sea ice. If the seas warmed and there wasn’t enough ice, then that affected the levels of krill in the southern ocean, and therefore reduced the available prey. It also made the penguins more vulnerable to other predators. If the opposite happened and there was too much sea ice, then foraging trips took longer and penguin chicks were less likely to survive.

Aptenodytes forsteri – the Linnean name for the emperor – is not in trouble yet, and its numbers may even grow in the years up to 2050. But this growth won’t last, and decline is likely everywhere. Climate change has already begun to affect penguin species much further north, in Argentina, by taking toll of young chicks.

Endangered class

For different reasons, the average rise in global temperatures forecast by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) could push the emperor into the endangered class.

“If sea ice declines at the rates projected by the IPCC climate models, and continues to influence emperor penguins as it did in the second half of the 20th century in Terre Adélie, at least two-thirds of the colonies are projected to have declined by greater than 50% from their current size by 2100,” Dr Jenouvrier said. “None of the colonies, even the southernmost locations in the Ross Sea, will provide a viable refuge by the end of the 21st century.”

The researchers end their paper by arguing that the emperor should – like the giant panda in China – become an icon for the conservation movement. They conclude: “We propose that the emperor penguin is fully deserving of Endangered status due to climate change, and can act as an iconic example of a new global conservation paradigm for species threatened by future climate change.” – Climate News Network.

– Yet another worrying piece of evidence on how human-made climate change is threatening the biodiversity of the planet, even in that “last bastion” of the Antarctic. The question is whether those iconic examples of species under threat from climate change like the penguins and their northern counterparts the polar bears are doomed to disappearance or whether their plight can really prompt the kind of lifestyle change and political and economic turnaround we need to put the brakes on climate change. I wish I could say I felt optimistic and had heard more than a lot of sympathetic “awwww”s in response to this latest distressing piece of penguin news.

See also:

West Antarctic Ice Sheet collapse unstoppable

Climate Risk to Icy East Antarctica

Ice Blog Post: Will the Antarctic share the Arctic’s Fate?

Feedback