Farewell to ‘Last Ice’ victims in a rapidly warming world

Ice Blog readers may remember the story of the two ice researchers and polar explorers who died when they broke through unexpectedly thin ice in the Canadian Arctic earlier this year. This week I had the chance to join friends and admirers of Marc Cornelissen and Philip de Roo at a ceremony held in their home country, the Netherlands. The unusually warm November weather, with people sitting out eating ice cream, seemed oddly apt for a tribute to two people who died doing climate research.

![]() read more

read more

Ice melt to motivate whizzkids?

And understanding that ice cores can tell us about 800,000 years of climate history tends to fascinate even the most unscientific of youngsters.

Not that the 160 young folk assembled recently in Bonn by the Hans-Riegel Foundation were lacking in scientific interest or talent.

The foundation, set up by the highly successful businessman who created HARIBO, (comes from HAnsRIegelBOnn, by the way) the “gummy bear” brand name, supports innovative educational projects with a view to encouraging talented young people to go into research. It awards prizes to school pupils in Germany and Austria for scientific projects.

Recently, 160 prizewinners were invited to a “Science Slam” in Bonn and a series of workshops and presentations – including a talk by renowned climate expert Mojib Latif. Mojib Latif is a professor for oceanology and climate dynamics at GEOMAR, the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, in northern Germany.

He has just been chosen as one of two winners of this year’s Deutscher Umweltpreis or German Environment Prize by the “Deutsche Bundesstiftung Umwelt”, one of Europe’s largest foundations. It’s the first time the award has been given to a climate scientist.

Latif, whose family background is Indian, is a well-known face on television. He has a talent for explaining complex climate phenomena in a way that ordinary people with no scientific background can grasp. As I listened to him addressing the young scientists, I could see how they were spellbound by his stories and anecdotes. And that makes it easier to digest the diagrams and figures that illustrate the workings of the global climate.

Latif holds his audience’s attention with a mixture of humour and examples from everyday life. He anticipates questions of the “skeptical” type, explaining the existence of natural trends and variations as well as human-made warming, and the wide range of scenarious covered by climate models.

When he turned to Greenland and to the Antarctic, I could see the fascination and curiosity in the eyes of the young audience.

The main message of this expert’s message was a mixture of concern at the rate of climate change and optimism that we have the technology to replace fossil fuels by renewables – and that the up-and-coming generation will use it to avert the worst.

Although he’s fairly certain we won’t be able to keep to the two-degree target, Latif says humankind just cannot be “so stupid” as to keep burning fossil fuels and heating up the atmosphere. If the applause of those representatives of the younger generation could be translated into positive action to combat climate change, his optimism may well be justified.

You can read what he told me in an interview after the encounter with Germany’s science whizzkids here:

“People power”, Shell and the Arctic

This week’s announcement that Shell is abandoning its controversial Arctic oil exploration for the “foreseeable future” provoked a wide spectrum of reactions – from disappointment, especially amongst politicians in Alaska, to the rejoicing of the environment campaigners.

Shell cites disappointing results, high operating costs – and an “unpredictable” regulatory environment as the reasons for the change in policy. The latter is the interesting one. Behind it lies an unmentioned but tangible ongoing shift in politics and society.

The tightening up of environment regulations in the USA is but one sign of the growing awareness that resources are limited, fossil fuels are harming the climate, and growth at the cost of environmental destruction is no longer acceptable.

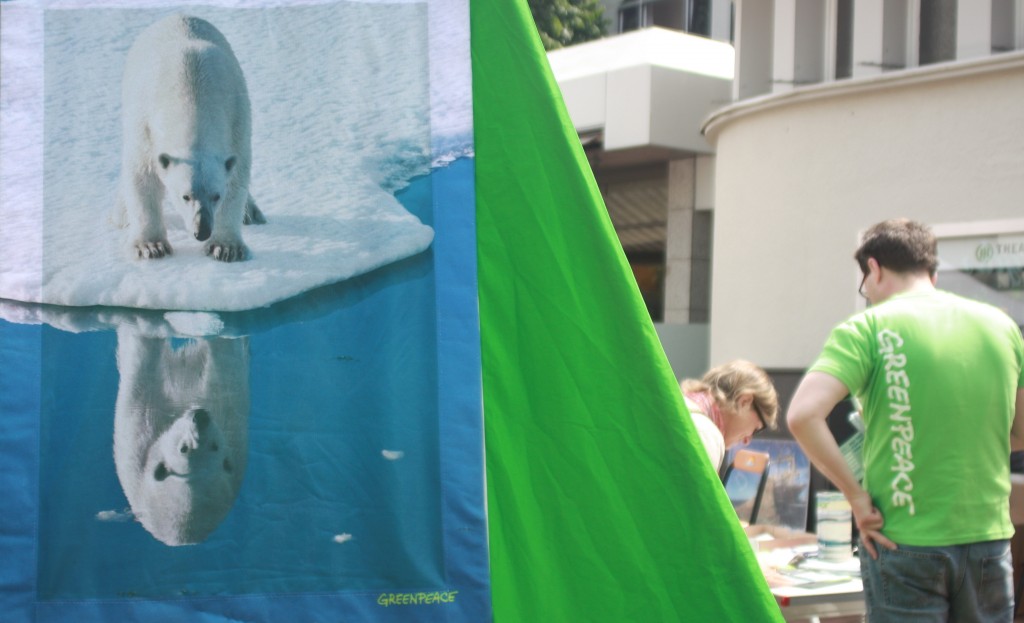

Campaign success

Environment campaigners have run a highly visible and successful campaign drawing attention to the risks of oil drilling for one of the world’s last remaining pristine regions, which is also one of the most dangerous because of low temperature, ice and poor visibility.

Greenpeace has been campaigning online and around the globe to stop Arctic oil drilling. This summer, kayakers staged spectacular protests in Seattle against Shell’s Arctic drilling plans.

Critics have succeeded in increasing awareness of the paradox behind the increasing accessibility of the Arctic to oil and gas exploration. Warming through increased CO2 emissions from the burning of fossil fuels is melting the Arctic ice. Exploiting that harm humankind has done to the environment with a view to extracting more oil -which in turn would cause further damage to the climate and the planet we live on – is cynical at best, self-destructive at worst.

Reputation at stake

All this is harmful to the image of Royal Dutch Shell. The Guardian quotes Greenpeace Arctic campaigner Ben Ayliffe:

“It is undeniable that the protests were a factor in Shell’s decision because the Arctic had become a defining environmental story”.

The paper quotes “company sources” as accepting that Arctic oil damaged the firm. “We were acutely aware of the reputational element to this programme”.

Shell had invested around seven billion US dollars in its Alaskan operations. But investors are worried about whether the company’s business models can hold against international climate protection goals.

Not the last word

The decision does not mean Shell will stay out of the region for good. Nor is it the end of oil exploration in the Arctic in general. BP’s Prudhoe Bay field and Gazprom’s Prirazlomnoye platform in the Pechora Sea – the object of the spectacular Greenpeace protests and Russian seizure of the organization’s boat and crew in 2013 – remain.

Nevertheless, Shell’s decision has to be a milestone in the ongoing struggle to protect the environment and halt climate change through a switch to renewable energies. Greenpeace International Executive Director Kumi Naidoo told journalists:

“It’s time to make the Arctic ocean off limits to all oil companies. This may be the best chance we get to create permanent protection for the Arctic and make the switch to renewable energy instead. If we are serious about dealing with climate change we will need to completely change our current way of thinking. Drilling in the melting Arctic is not compatible with this shift.”

This week I interviewed German climate expert Mojib Latif, who is being awarded a key European Environment prize for his tireless efforts to inform people about the risks of climate warming and the need to decarbonize the economy. His key message was that we have the technology to make a real difference. But it will only work if people take that to heart and don’t leave it up to the politicians, he says.

Shell’s departure from Alaska shows what “people power” can do.

Can we still avert irreversible ice sheet melt?

Earlier this week, I was able to follow up my last talk with Professor Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), after he returned from the Paris climate science forum. After the publication of the study he was involved in on paleoclimatic data linking global temperature with sea level rise, and having heard his views on the science consensus ahead of the December UN summit in Paris, I wanted to know how he views the prospects for the polar ice sheets.

A question I return to often is whether anything we do to reduce emissions from now onwards – given that huge damage has already been done by our fossil fuel emissions and that the CO2 will remain in the atmosphere for a very long time to come – can prevent the ice sheets in the Antarctic and Greenland from reaching a “tipping point”.

Professor Rahmstorf gives this definition of a “tipping point” – which can mean different things to different people in different contexts:

“Climate tipping points are points of no return, where you cannot stop a process that has been set in motion. It’s a bit analogous to the situation where you are sitting in a rowing boat and you lean over a bit to one aside and not much happens. Then you lean a bit more and a tipping point comes where the boat simply tips over. One of these points of no return is with our continental ice sheets, where their further melt-down becomes inevitable and unstoppable. And we have to realize that we have enough continental ice on this planet to raise global sea level by more than 60 metres. That means we cannot afford to lose even a very small fraction of that ice without drowning coastal cities and small island nations.”

Is the boat still afloat?

But, of course, we are already losing ice at a worrying rate. Rahmstorf cites recent research showing that at least a part of the West Antarctic ice sheet has already been destabilized.

“We probably have already crossed the tipping point for a part of West Antarctica. That is probably going to already commit us to about three metres of sea level rise.”

Of course this is not likely to happen in the very near future. But the problem with the tipping points is, of course, that there is no going back, as Rahmstorf explains:

“Sea level has already risen 20 centimetres globally since the late 19th century, due to modern global warming, which is very basic physics. It’s melting continental ice sheets. And also the oceans are being heated up, which expands the ocean water, because warm water takes up more space. And by the year 2100, with unmitigated emissions, we are looking at one meter of sea level rise, which already, for vulnerable coastal areas like delta regions, like Bangladesh for example, will dramatically increase the storm surge risk. But sea level rise will not stop in the year 2100, because the ice sheets are actually quite slow to melt, and within the next decades, we will be causing a long-term sea level rise commitment by several metres for every degree of global warming that we cause.”

Greenland – and Miami, St. Petersburg, Bangladesh…

Record melting appears to be happening on Greenland at the moment. I asked Rahmstorf how safe the world’s biggest island and the largest area of freshwater ice in the northern hemisphere (See also the Ice Island in Pictures) is from reaching a point of no return. He wasn’t able to give a reassuring answer:

“We don’t know exactly where the tipping point is for the Greenland ice shield is. The IPPC estimates anywhere between one and four degrees of global warming. We are already at one degree warming, so we may well cross that tipping point in the next decades.

In the review of the relation between global temperature and sea level rise from polar ice disintegration I discussed in the last blog post, Rahmstorf and his colleagues found that just a slight further rise in temperature might equate to a rise in global sea level of up to six metres. I asked him what that would mean for the world right now:

“There would be quite a number of large coastal cities I cannot imagine could still be defended. Think of New York city for example. Or Miami would be one of the first cities to go. St. Petersburg, Alexandria, Manila – you name them. Once you are talking about metres of sea-level rise, the consequences would be quite catastrophic. Especially as it is to be feared that people will not react proactively by move away from the danger zone, but will probably stay in their cities until a major storm surge hits. Like Hurricane Katrina hitting New Orleans, which also was a case where experts had warned for a long time that the city was in danger, once the next hurricane strikes, but people still didn’t act according to the precautionary principle. As they should have, and as we must do to prevent a climatic disaster in future.”

Can we keep the ice chilled?

So what would we have to do to keep sea level in check?

“Emissions would have to be close to zero by mid-century, so we are not talking about small cosmetic adjustments, but a transformation of our energy system, decarbonization, that is getting out of the carbon-based energy system. The good news is that the technologies to do that are available. It’s all about mustering the political will. And, of course, fighting the particular interests which are opposing this transformation.”

Stefen Rahmstorf is not one of those scientists who prefer to sit on the fence and leave the interpretation of his research and their implications up to the politicians. He is convinced only rapid action to stop emissions can prevent catastrophic climate change – including the melt of the polar ice.

I have interviewed him on previous occasions in the last few years. This time, I was surprised by his optimistic stance on whether the international community can still do anything in time to stop global warming from reaching the dangerous level of two degrees (or even one point five, as Rahmstorf and others say would be far preferable):

“There’s still a good chance that a strong agreement coming out of the Paris summit in December could mean we could avoid the Greenland tipping point. I am cautiously optimistic that Paris will reach a meaningful agreement, not necessarily one that guarantees that we will stay below two degrees global warming, but one that will be seen in hindsight as a real turning point, from where emissions started to fall soon after. The key point is – the sooner we stop global warming, the better the chances are that we avoid future critical tipping points.”

All we need, says Rahmstorf, is the political will to make use of the technologies available, take on the fossil fuels lobby, and clean up our energy system.

Listen to my interview with Stefan Rahmstorf on DW’s Living Planet this week.

Polar ice set for six-metre sea level rise?

Small increases in global average temperature may eventually lead to sea level rise of six metres or more, according to evidence from past warm periods in Earth’s history.

That was the worrying message from a paper published in the journal Science this week. The researchers, part of the international “Past Global Changes” project, analysed sea levels during several warm periods in Earth’s recent history, when global average temperatures were similar to today or slightly warmer – around 1°C above pre-industrial temperatures.

I was able to talk briefly to one of the authors, Stefan Rahmstorf from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), who was in Paris at the international scientific conference “Our common future under climate change” this week. (The article I wrote on that event, billed as the biggest climate science gathering ahead of the key COP in Paris in December, and the full interview with Rahmstorf are online now).

Rahmstorf described the new study on polar ice sheet disintegration and sea level as “a review of our state of knowledge about past changes in sea level in earth’s history, especially looking at all the data we have on past warm periods, due to the natural cycles of climate – the ice age cycles – that come from the earth’s orbit.”

He went on: ”We have had warmer times in the past, the last one was about 120,000 years ago, and we find that invariably, during these warmer times, the sea level was much higher. It was at least about six meters higher than today, even though temperatures were only a little bit higher, maybe one to three degrees warmer – depending on what period you are looking at – compared to the pre-industrial climate.”

Bad news for coastal dwellers

Not happy reading for anyone living close to the coast, if you look at temperature development today:

“Basically the message is: the kind of climate we are moving towards now – even if we limit warming to two degrees – has in the past always been associated with a sea level several metres higher, which would of course have catastrophic consequences for many coastal cities and small island nations.”

With warming currently on course to reach four degrees and more by the end of this century if greenhouse gas emissions continue on their present trajectory, this message adds yet another piece of evidence to motivate the world’s governments to come up with a new World Climate Agreement at the UN Paris summit at the end of the year – and to get moving towards a zero-carbon economy asap.

The interdisciplinary team of scientists concluded that during the last interglacial warm period between ice ages 125,000 years ago, the global average temperature was similar to the present, and this was linked to a sea-level rise of 6 to 9 metres, caused by melting ice in Greenland and Antarctica. Around 400,000 years ago, when global average temperatures were estimated to be between 1 to 2 degrees Celsius higher than –pre-industrial levels, sea level reached 6 to 13 meters higher. The lead author of the study, Andrea Dutton from the University of Florida, told journalists global average temperatures were similar to today during these recent interglacial periods, but polar temperatures were slightly higher. However, she stressed: “The poles are on course to experience similar temperatures in the coming decades”.

The Arctic is currently warming faster than the global average. IPCC estimates indicate that it could be almost two degrees warmer by 2100 compared with the temperature from 1986 to 2005 – IF the two-degree target is adhered to. Otherwise, it could rise by as much as 7.5°C.

Speed of sea level rise hard to predict

The authors of the study stress that the further back you go (they tried to estimate sea level as long as three million years ago), the more difficult it gets to calculate precisely how high sea level was, given that geological forces push and pull the Earth’s surface and can also cause vertical movement measuring tens of metres. This makes it hard to separate the geological changes in shoreline position from sea level rise caused by polar ice sheet disintegration.

Still, the authors point out that small temperature rises of between one and three degrees were, in the past, like today, linked with magnified temperature increases in the polar regions, which lasted over many thousands of years.

They conclude that even keeping to the overall two-degree warming limit is no guarantee: “Even this level sustained over a long period of time carries substantial risk of unmanageable sea level rise, not least because carbon dioxide remains in the atmosphere for over a thousand years”.

The researchers are not able to say how fast sea levels rose in the past, which would be a key piece of information for planning adaptation. Further research will be necessary for that.

Co-author Anders Carlson of Oregon State University says by confirming that our present climate is warming to a level associated with significant polar ice-sheet loss in the past, the study us providing “perhaps the most societally relevant information the paleo record can provide”.

Carlson heads the PALSEA2 Working Group, hosted by the Past Global Changes (PAGES) project, which used computer models and evidence from around the globe to come up with the conclusions in the study.

Stefan Rahmstorf draws a clear conclusion from the results of this research and other recent studies on instabilities in the Antarctic ice sheet and changes in ocean currents:

“This really calls for limiting warming to 1.5 degrees. And it is still feasible to limit warming to 1.5 degrees. But that requires a much stronger political will than we currently have”.

Still, the Potsdam professor is more optimistic than he used to be that advances in renewable energy and other technologies and growing awareness of the negative impacts climate change is already having around the globe could mean the UN Paris conference at the end of the year will mark a turning point.

Not that he thinks Paris can “do it all”. As you’ll see if you read my interview with him, he is hoping for the start of a process similar to the Montreal Protocol, where the original agreement was not too strong, but worked eventually by toughening up as it went along. Now that would be really good news. He told me it was time to “turn the tide of rising emissions”. Here’s hoping it happens in time to keep the sea level around the world well below that six metres that were there in the past.

Feedback