Climate action from Peru to Paris

Today is the first of December. It’s the start of the meteorological winter in the northern hemisphere, towards the end of what looks set to be the warmest year since records began. It is also the day when the annual UN climate conference gets underway in Lima, Peru. Negotiators from around the world will try to hammer out the details of a new World Climate Agreement to halt global warming by reducing CO2 emissions. For our polar ice, that agreement can’t come fast enough.

After five years of frustration following the failure of the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009, 2014 may well go down in history as the year when climate change made a comeback onto the international agenda. Although there is still one year to go until the key Paris meeting which is scheduled to come up with a new World Climate Agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol, 2014 has seen several milestones on the path to a low-carbon future.

In September, the UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon gave the issue top priority, by holding his own special climate summit in New York. It was accompanied by marches in the USA and other parts of the world, organized by a growing grassroots movement to combat climate change. Meanwhile, the world’s biggest emitters, China and the USA, finally signaled their intention to commit to action on climate change.

No time for delay

The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, has left no doubt about the need for urgent action, says Professor Stefan Rahmstorf from Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:

“We see that global temperatures have risen by almost one degree centigrade in the last 100 years, we see that global sea level has risen by nearly 20 centimeters in the last 100 years. We see that the mountain glaciers and the Arctic ice cover is in retreat, the continental ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are shrinking, losing mass, contributing to sea level rise, we see extreme events on the rise. For example the number of record-breaking hot months has increased five fold as compared to what you get by chance in a stationary climate.”

The international community has agreed, based on the scientific evidence available, that a temperature rise of two degrees is the maximum possible without exposing the world to potentially devastating climate change. That means limiting the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet. But with those emissions still on the rise, that goal is nowhere in sight, says Rahmstorf, and climate change is already having an impact after just under one degree of warming:

“If we don’t stop this process, we will go well beyond two degrees centigrade, and we will leave the range we are familiar with throughout human history. We will be way outside that into uncharted and I think very dangerous waters.”

Peru prepares the way for Paris

Experts see the world on track for a temperature rise of at least four degrees, unless emissions are reduced substantially in the very near future. The latest figures indicate that to stay within the two degree limit, emissions would have to peak within the next ten years and the world become virtually carbon-neutral in the second half of this century.

Peru’s Environment Minister and COP 20 President Manuel Pulgar-Vidal told me in Bonn this summer he was optimistic about the Lima meeting. (Pic: Quaile)

That is why Peru, like every climate conference, is important, says UN climate chief Christiana Figueres. She stresses that climate protection is an ongoing process. Countries have until March 2015 to put their planned contributions on the table. The EU made a start by announcing its targets last month. The USA and China went on to give encouraging signals:

“The fact is that most countries around the world are currently doing their homework and figuring out on a national scale what is financially, politically, economically, technically possible for them to contribute towards the solution,” says Figueres.

But while that homework continues in the countries of the world, the negotiators assembling in Lima will have to make progress on drafting the universal climate agreement, which is scheduled to be agreed in Paris in December 2015 and to come into effect in 2020.

A price on CO2

Ottmar Edenhofer is the chief economist at the Potsdam Climate Institute. He is also co-chair of the IPCC group concerned with ways of tackling climate change. He says the world has only around 20 to 30 years left to solve the emissions problem. He stresses it is not a question of technology. Alternative energy technologies are there to solve the problem. Yet fossil fuels have been enjoying a renaissance, says the climate expert. The key, he says, is to put a price on carbon, making it too expensive to pump CO2 into the atmosphere. The world only have a limited carbon budget. That means we can only put another one thousand gigatonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere to keep temperature rise below the two-degree threshold and avoid the risk of what Edenhofer describes as “very severe climate change impacts”.

“Space to store CO2 in the atmosphere is becoming scarce”, Edenhofer explained to me recently during a visit to Potsdam. “And when things are scarce, you have to put a price on them. That is the only way to show investors, consumers and companies where they should be investing their money.” The window of opportunity is closing, says Edenhofer. If we keep on with business as usual, we will have used up all our carbon budget in two to three decades.

UN climate chief Figueres agrees that putting a price on pollution by CO2 is a very important component of the shift towards a low carbon economy.

“What we have done over the past 150 years is assumed there is no cost to the irresponsible use of the environment, and we have proceeded as though the environment were constantly renewable, where it is not”, Figueres told me in an interview conducted in her office here in Bonn, right next to our Deutsche Welle building. Putting a price tag on CO2 emissions would mean they could be costed in economic decision-making.

Haggling out the details

The negotiators in Lima have their work cut out for them. Countries with large fossil fuel reserves are reluctant to agree to emissions reductions which would destroy their source of revenue. But Edenhofer is optimistic that ultimately all countries will realize that climate change will pay off in the end.

„We have to assume that people will see sense. They will realize that the long-term consequences of business as usual will be irreversible climate change, with all the problems that brings with it”.

The economist says protecting the climate would also bring the kind of short-term benefits politicians are looking for. He cites the change in China’s policies as an example:

“The drastic air pollution in Beijing is already making it less attractive as a business location. And the reason the Chinese government is thinking very seriously about reducing emissions is because it would also be a step towards improving their air quality.”

Funding boost for UN talks

After years of stagnation and frustration, there are signs that progress is being made on climate change. At a key meeting in Berlin this month, countries pledged a total of almost 10 billion dollars to the Green Climate Fund, which was set up to help poorer countries adapt to climate change. This could motivate developing countries and emerging economies to sign up to a new world climate agreement. So far, many of them have been reluctant to limit their own emissions, as the wealthy industrialized states are the ones who have caused the problem by emissions in the past.

Although both the money pledged for adaptation and the emissions cuts proposals currently on the table are still insufficient and things are moving slowly, German scientist Rahmstorf compares the likelihood of a breakthrough to the fall of the Berlin Wall, 25 years ago.

“If you had asked people just a few months before that how likely it was that the wall comes down, nobody would have said it’s going to happen”, says the Potsdam expert and IPCC author. He says these kind of processes in society are hard to predict – and the signs are encouraging.

He cites the “huge success story” of renewable energies and the considerable emissions reductions by the EU countries since 1990 as encouraging signs. This did not hamper economic growth, says Rahmstorf:

“It shows that your can decouple emissions from economic growth and welfare”.

Ultimately, halting climate change is not something which can be achieved solely within the UN negotiations. This year for the first time a pre-conference meeting was held in Peru to involve non-governmental groups in the process. The transition to a climate-saving low-carbon society requires action across the board. But it is the governments of the world who have to enter into binding agreements, and that means plenty of hard work ahead for the negotiators in Peru over the next two weeks.

Listen to my Peru conference preview on Living Planet.

Arctic icon in decline

As I plan my coverage of this year’s annual UN climate conference, this time in Peru, a news item from WWF pops up in my mail box. The organization is concerned that the number of polar bears in the Beaufort See in Alaska and in north-western Canada has dropped by around 40 percent in the last ten years. Now that is a very worrying statistic.

It is based on a study published in the journal Ecological Applications: Polar bear population dynamics in the southern Beaufort Sea during a period of sea ice decline.

In 2004, it seems 1,500 polar bears were counted. The latest count showed just 900. Declining sea ice and a lack of prey seem to be the likeliest causes. Another piece of evidence to justify the decision in 2008 to list polar bears under the US Endangered Species Act.

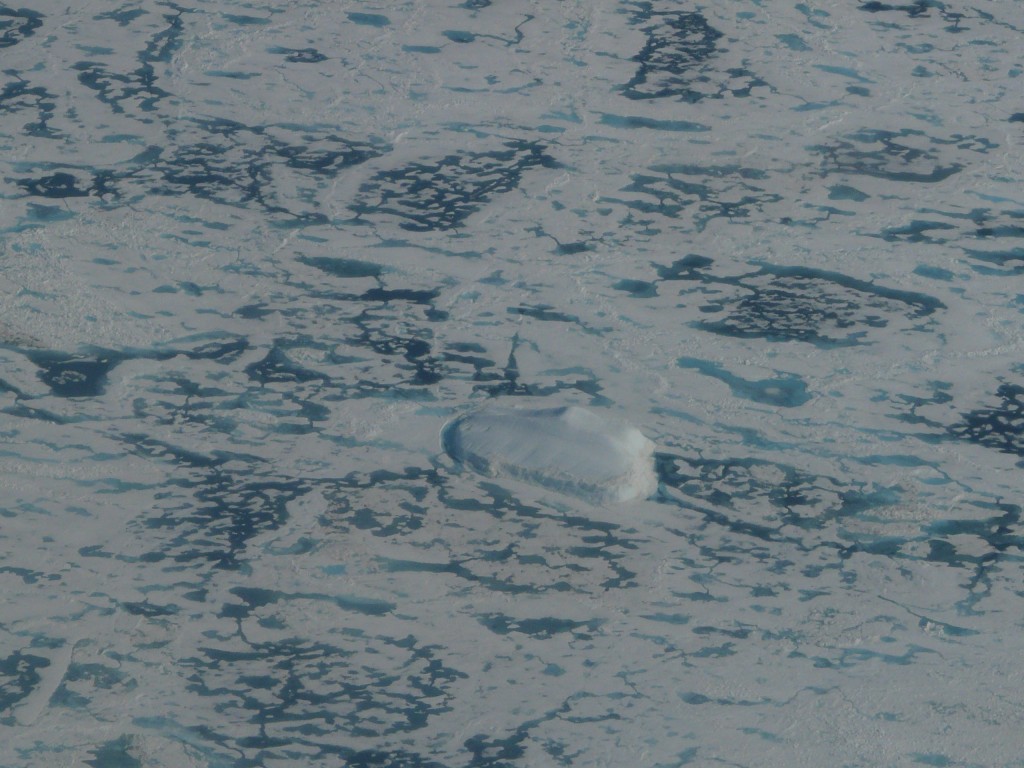

WWF fears the worrying trend will continue if climate change is not halted. There are only between 20,000 and 25,000 polar bears left in the world. With the average air temperature in the Arctic a good five degrees centigrade higher than it was a hundred years ago, it is hardly surprising that nature is struggling to cope. As the sea ice declines, the bears are losing their habitat. You might also remember the pictures of all those walruses on the beach a few weeks ago. They too, were affected by the decline of the sea ice where they usually rest between dives.

So what can we do to halt the decline in the polar bear population? This brings me back to the forthcoming climate conference in Peru. I am finding it difficult to arouse interest in this year’s meeting. “Paris next year is the important one”, I hear. So does climate action just get put on hold for another 12 months? Tell that to the polar bears. One single conference cannot save the world from the climate catastrophes that could lie ahead if the world does not manage to reduce its emissions drastically in the next few years. UNEP’s “Emissions Gap Report 2014”, just published yesterday, says we have to be carbon-neutral by the 2nd half of this century to keep temperature rise below two degrees centigrade. There is still a huge gap between the pledges made by countries within the UNFCCC framework and what is necessary for that. Emissions would have to peak within the next ten years, says the UNEP report, based on the latest IPCC data. Otherwise we risk severe and irreversible climate change with all the droughts, floods and other impacts that come with it.

Given the need for urgent action, I fail to understand how anyone can say “forget Peru, wait for Paris”. I would be the first to stress that these conferences alone cannot halt climate change. The switch to renewable energy is already underway. But ultimately, governments have to agree to binding targets. We have seen encouraging signs from the top emitters China and the USA. Without those international negotiations, this is unlikely to have happened. Let us take the Peru conference as an opportunity to focus world interest on the urgency of climate action. Countries have to keep doing there homework. I don’t know if we will be able to turn our energy policies around in time to save the bears. But if they are to have any chance – at the risk of sounding clichéd: the time for action is now, and any major climate event is a chance to say so.

Berlin Wall – Hope for Arctic?

The statement by veteran Arctic researcher Peter Wadhams that the Arctic could be ice-free in summer as early as 2020 sparked a lot of discussion. Recently I had the chance to talk to Professor Stefan Rahmsdorf, Professor of Physics of the Oceans and head of Earth System Analysis at Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) about Wadham’s forecast.

![]() read more

read more

Acid Arctic Ocean and Russell Brand?

Is ocean acidification a term you are familiar with? If you are a regular Ice Blog reader, I would like to think you will be. But I am prompted to ask this question because the term came up during a discussion at a weekly evening class I attend, and I was flabbergasted that none of the people there had a clue what it meant. These were all university-educated professionals. That means we in the media have our work cut out for us explaining how climate change is making the seas more acidic, and why this is something we should be worried about.

This incident has reminded me that we journalists have to avoid assuming that everyone is familiar with the terms we use in our coverage on a regular basis. Climate change is the kind of topic where you want to reach a specialist audience, but also the vast majority of the population. We all have to change our habits to reduce CO2 emissions, and we all have to vote for the politicians who have the responsibility for energy and environment policy. That means we need to talk about the problems in a way everybody understands.

I am encouraged to see the BBC website had a longer article on the threat of ocean acidification a few days ago. I don’t think it has made its way into the tabloids though, correct me if I am wrong.

I was made very aware of the issue during a trip to Arctic Spitzbergen in 2010 with a team of scientists monitoring just what happens to the life forms in the sea when it becomes more acidic because it is absorbing so much of the CO2 we emit. The polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster.

Greenpeace provided scientists with logistic support for the ocean acidification experiments off the coast at Ny Alesund, Spitzbergen. (Pic: Irene Quaile)

Towards the end of last year, I interviewed Professor Alex Rogers from the University of Oxford, who is also the scientific director of the International Programme on the State of the Oceans, which had just published a major study on acidification.

Listen to the interview:

He told me: “The oceans are taking up about a third of the carbon dioxide we’re producing at the moment. While this is slowing the rate of earth temperature rise, it is also changing the chemistry of the ocean in a very profound way.”

Carbon dioxide reacts with sea water to form carbonic acid. Gradually, this makes oceans more acidic.

Threat to marine life

Sea water is already 26 percent more acidic than it was before the onset of the Industrial Revolution. According to the IPSO report, it could be 170 percent more acidic by 2100.

Over the last 20 years, scientists around the world have been conducting laboratory experiments to find out what that would mean for the flora and fauna of the oceans. Ulf Riebesell of the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, a lead author of the report, conducted the world’s first experiments in nature, off the coast of the Arctic island of Svalbard in 2010. This was the project I visited.

Giant test-tubes were lowered into the ocean to capture a water column with living organisms inside it. Different amounts of CO2 were added to simulate the effects of different emissions scenarios in the coming decades. The experiments showed that increasing acidification decreases the amount of calcium carbonate in the sea water, making life very difficult for sea creatures that use it to form their skeletons or shells. This will affect coral, mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish as well as fish and other organisms. Scientists say some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future.

Hard times for coastal residents

All this will have severe economic and social consequences. Ultimately, acidification will affect the food chain. Tropical and sub-tropical areas with warm-water corals are going to suffer. Coral reefs are home to numerous species, serve as nurseries for fish and are a valuable tourist attraction. They also protect coastlines against waves and storms.

At the same time, the polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster. Riebesell told me the experiments in the Arctic indicate that the sea water there could become corrosive within a few decades. “That means the shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve.” What a horrific prospect.

The Antarctic is already affected. IPSO’s Alex Rogers told me: “We’re seeing instances where we’re finding tiny shelled molluscs, tiny snails that swim in the surface of the oceans, with corroded shells.”

These creatures play a key role in the marine food chain, supporting everything from tiny fish to whales. “One of our primary sources of marine-derived protein is in rapid decline,” says Monty Halls, manager of the UK-based Shark and Coral Conservation Trust. He describes ocean acidification as the “most serious threat to our children’s welfare.” Monty is working to produce video and cartoon material to interest the younger generation in the need to change our behavior to protect marine life.

Two German scientists Antje Funcke and Konstantin Mewes have written and illustrated a children’s story called Tipo and Tessi to make kids aware of the need to protect the ocean. So far, it has only been published in German. The English translation is available, but so far there is a lack of funding for publication.

Vicious circle of climate change

Scientists are also concerned about a feedback effect that will further exacerbate global warming. In the long run, the ocean will become the biggest sink for human-produced CO2, but it will absorb it at a slower rate. That means the more acidic the ocean becomes, the less capacity is has to act as a buffer.

Alex Rogers sees a further problem: “Carbonate structures actually weigh down particular organic carbon. In other words, they help carbon to sink out of the surface layers of the ocean into the deep sea. Anything that interferes in that process can potentially accelerate the rate of CO2 increase in the atmosphere.”

And that would be very dangerous. “The rates of CO2 increase we are seeing at the moment are probably as high as they’ve been for the last 300 million years,” says Rogers.

The IPSO scientists draw an unsettling comparison between conditions today and climate change events in the past that have resulted in mass extinctions. They say a lot of these major extinction events occurred in connection with high temperatures and acidification, similar effects to the ones that we are experiencing today.

The BBC article I mentioned earlier also mentions new research by scientists at Exeter University, indicating that increasing acidity creates conditions for animals to take up more coastal pollution, like copper. That would mean not only creatures with calcium-based shells would be endangered.

Find a celebrity champion?

The experts stress that it is not too late to halt the acidification process, although the CO2 will remain in the oceans for thousands of years. This brings me back to the topics of recent Ice Blog posts: the UN climate negotiations and the need for urgent action. And of course, to the mention in the title above of the British comedian Russell Brand. This relates to another issue I have been writing about recently: the question of celebrity involvement and whether that can help inform people about and interest them in topics like climate change and the acidification of our oceans. My commentary on this, with regard to Leonardo di Caprio at Ban Ki-moon’s September summit in New York, sparked some interesting discussions.

Just this morning I was reading about Russell Brand and how his new book calling for a revolution on all kinds of issues is attracting huge interest. I have noticed that people otherwise completely uninterested in politics and social issues are at least paying some attention because their favourite comedian is talking about them. Maybe we have to get Russell Brand on board. I’m not sure what kind of action he would advocate, but there would certainly be a lot fewer people who could say they’d never heard of ocean acidification.

Can UN and EU take the heat off Alaska?

It is with a heavy heart that I write this first blog post since my holiday, catching up with the latest climate news. A piece by Alex Kirby of Climate News Network drews my attention to the fact that temperatures in Barrow, Alaska, one of the first places to feature on the Ice Blog when it was created in 2008, have risen by an astonishing 7°C in the last 34 years (looking at the average October temperature). As Alex Kirby puts it, “an increase that, on its own, makes a mockery of international efforts to prevent global temperatures from rising more than 2°C above their pre-industrial level”. We need more climate action

![]() read more

read more

Feedback