Why Brexit bodes ill for the Arctic

EU headquarters in Brussels. The Arctic is high on the European Union’s foreign policy agenda. The EU Council just published new Conclusions on the Arctic (Pic: I.Quaile)

Today’s Ice Blog post was going to be about permafrost, with the the International Conference on Permafrost drawing to a close after a week in Potsdam outside Berlin today. But the Brexit decision is casting a shadow over a lot of things today – and that includes the international spirit of cooperation that is the key to successfully tackling the all-embracing challenge of climate change and its destructive impacts on Arctic ice and permafrost. And while the permafrost is melting, the political atmosphere and social climate here in Europe are definitely becoming much colder.

British breakaway bad news for science

Not that the decision in itself will necessarily have a direct, immediate impact. Scientific research will go on in Britain and other parts of the world regardless of whether or not the country is a member of the European Union. The UK has a long tradition of polar exploration and research. But research relies on international cooperation – and the EU has become one of the key funders of Arctic research in recent decades.

British Arctic marine biologist collaborating with Dutch colleagues. (Ny Alesund, Spitsbergen, Pic: I.Quaile)

Leading scientists including Stephen Hawking have said a Brexit would be a disaster for UK science in general.

A group of 13 Nobel prize-winning scientists have also warned that leaving the EU would pose a “key risk” to British science. The group, which includes Peter Higgs, who predicted the existence of the Higgs boson particle, say losing EU funding would put UK research “in jeopardy”.

“Inside the EU, Britain helps steer the biggest scientific powerhouse in the world”, the group claim in a letter to the British Daily Telegraph.

While the other side insisted leaving the EU would not be damaging, the majority of scientists appear to be in favour of Britain remaining in the EU. 83% of scientists polled opposed Brexit.

International “give-and-take”

It is not just a matter of EU funding for British science. The scientist group stressed that British scientists should also be involved in the EU as a hub of innovation and research. They say more than one in five of the world’s researchers move freely within the EU boundaries.

Restricting this free movement is one of the key aims of the Brexit campaign. As a British journalist working in Germany, I have experienced the benefits of being able to travel, study and work in other European countries for many years.

Future generations bear the brunt

The majority of young people who voted apparently voted to stay in the EU. This is the generation that stands to gain or lose by the Brexit decision. If I think of all the dedicated young scientists from Britain and other countries I have interviewed over the years, working across borders on issues that are certainly not limited to one local area, it makes me sad and even angry that they stand to lose out because of a campaign that was based on negative sentiments like the desire to keep foreign workers and refugees out of Britain, or vague and unfounded claims that everything that does not work in Britain is the fault of the EU. No, it’s not perfect, but I doubt that many of the arrangements that protect nature in the UK and other European countries would be in place without the involvement of Brussels. And how is a body like the EU going to change and reform if not through pressure from within?

Anyone who cares about the environment knows that without international cooperation, it is not possible to protect our air, land, water and atmosphere against abuse and pollution.

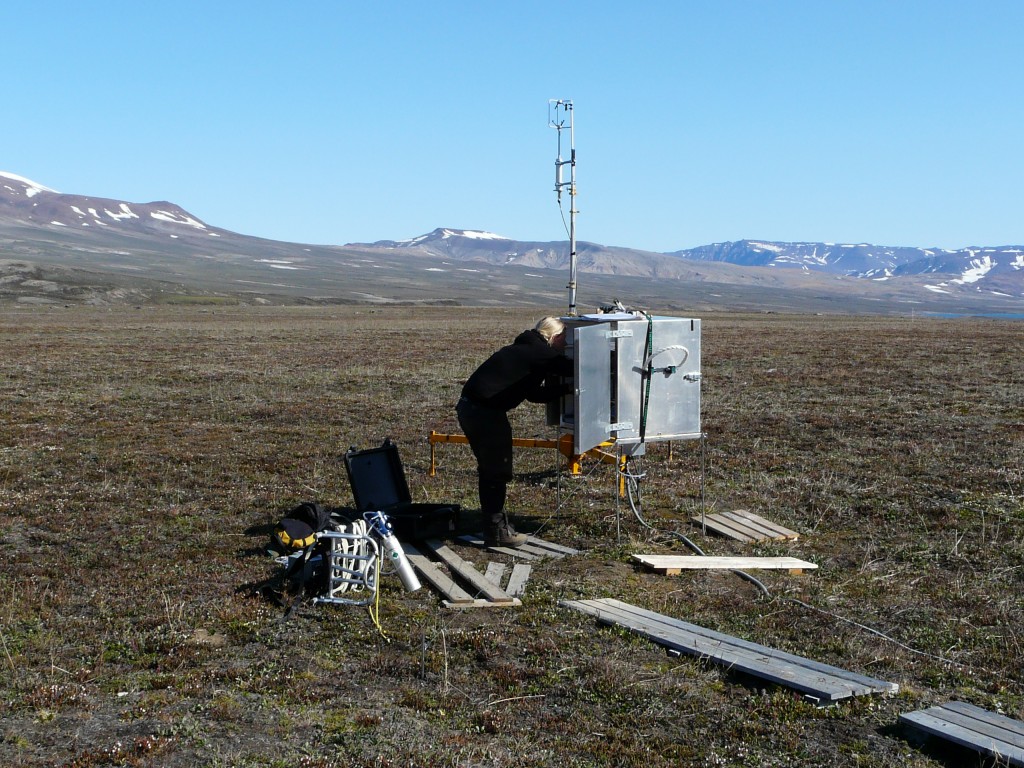

Measuring CO2 emissions from summer permafrost at Zackenberg, Greenland. GLobal emissions warm the Arctic, melting permafrost reinforces the global warming effect. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Not just about money

In an article for the MIT Technology Review, Debora MacKenzie says the EU budgeted 74.8 billion euros for research from 2014 to 2020. Brexiters, she writes, say British taxpayers should simply keep their contribution and spend it at home:

“They’d take a serious loss if they did. Britain punches above its weight in research, generating 16 percent of top-impact papers worldwide, so its grant applications are well received in Brussels. Between 2007 and 2013, it paid 5.4 billion euros into the EU research budget but got 8.8 billion euros back in grants. British labs depend on that for a quarter of public research funds, a share that has increased in recent years. A cut in that funding after Brexit could drag down every field in which British research is prominent—which is most of them.”

MacKenzie also quotes Mike Galsworthy, a health-care researcher at University College London who launched the social-media campaign Scientists for EU:

“It’s not just funding, EU support catalyzes international collaboration.” Galsworthy puts his finger on a key issue here:

“The EU funds research partly to boost European integration: for most programs you need collaborators in other EU countries to get a grant. This isn’t a bad thing, as collaborative work tends to mean more and higher-impact publications.”

Indeed.

International team measure ocean acidification off Spitsbergen, as part of EU EPOCA programme. (Pic.: I.Quaile)

One shared world

The spirit behind the vote to leave the EU is to a large extent based on nationalism and xenophobia. If it were to prevail, it would lead us backwards and result in fragmentation. That has to be bad news for those of us who believe in working together across borders for the greater good of the planet as a whole. Climate warming is a global phenomenon. We need to work together to tackle it. The icy regions of the northern hemisphere may belong geographically to individual countries like the USA, Canada, Russia or Norway. But in today’s industrialized, globalised world, no single player alone can stop the ice from melting. Or regulate the increased fishing, shipping or exploitation of natural resources in once pristine areas now becoming rapidly accessible.

Feedback