“People power”, Shell and the Arctic

This week’s announcement that Shell is abandoning its controversial Arctic oil exploration for the “foreseeable future” provoked a wide spectrum of reactions – from disappointment, especially amongst politicians in Alaska, to the rejoicing of the environment campaigners.

Shell cites disappointing results, high operating costs – and an “unpredictable” regulatory environment as the reasons for the change in policy. The latter is the interesting one. Behind it lies an unmentioned but tangible ongoing shift in politics and society.

The tightening up of environment regulations in the USA is but one sign of the growing awareness that resources are limited, fossil fuels are harming the climate, and growth at the cost of environmental destruction is no longer acceptable.

Campaign success

Environment campaigners have run a highly visible and successful campaign drawing attention to the risks of oil drilling for one of the world’s last remaining pristine regions, which is also one of the most dangerous because of low temperature, ice and poor visibility.

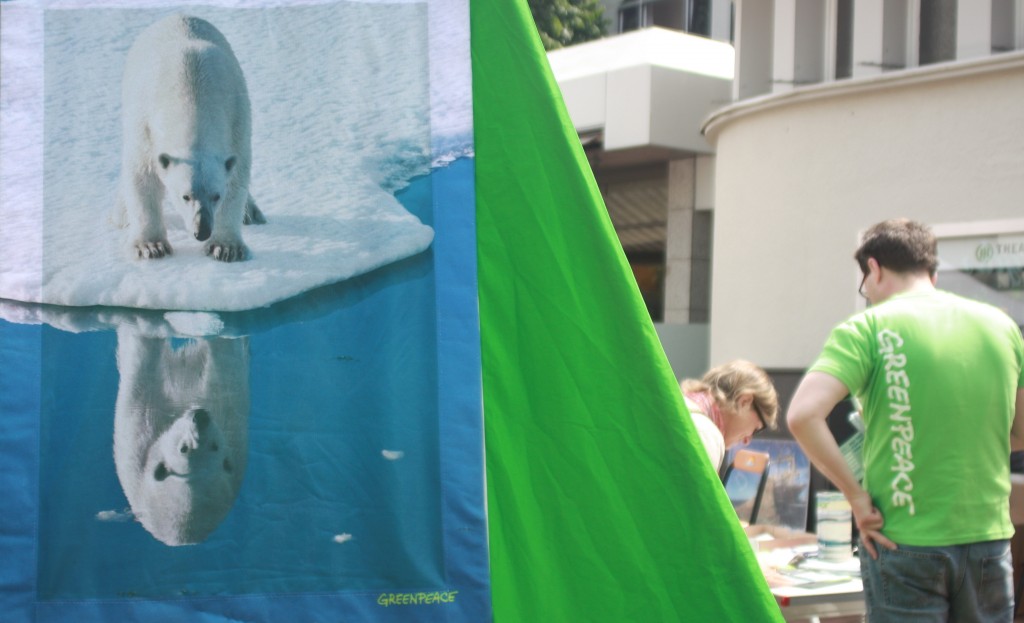

Greenpeace has been campaigning online and around the globe to stop Arctic oil drilling. This summer, kayakers staged spectacular protests in Seattle against Shell’s Arctic drilling plans.

Critics have succeeded in increasing awareness of the paradox behind the increasing accessibility of the Arctic to oil and gas exploration. Warming through increased CO2 emissions from the burning of fossil fuels is melting the Arctic ice. Exploiting that harm humankind has done to the environment with a view to extracting more oil -which in turn would cause further damage to the climate and the planet we live on – is cynical at best, self-destructive at worst.

Reputation at stake

All this is harmful to the image of Royal Dutch Shell. The Guardian quotes Greenpeace Arctic campaigner Ben Ayliffe:

“It is undeniable that the protests were a factor in Shell’s decision because the Arctic had become a defining environmental story”.

The paper quotes “company sources” as accepting that Arctic oil damaged the firm. “We were acutely aware of the reputational element to this programme”.

Shell had invested around seven billion US dollars in its Alaskan operations. But investors are worried about whether the company’s business models can hold against international climate protection goals.

Not the last word

The decision does not mean Shell will stay out of the region for good. Nor is it the end of oil exploration in the Arctic in general. BP’s Prudhoe Bay field and Gazprom’s Prirazlomnoye platform in the Pechora Sea – the object of the spectacular Greenpeace protests and Russian seizure of the organization’s boat and crew in 2013 – remain.

Nevertheless, Shell’s decision has to be a milestone in the ongoing struggle to protect the environment and halt climate change through a switch to renewable energies. Greenpeace International Executive Director Kumi Naidoo told journalists:

“It’s time to make the Arctic ocean off limits to all oil companies. This may be the best chance we get to create permanent protection for the Arctic and make the switch to renewable energy instead. If we are serious about dealing with climate change we will need to completely change our current way of thinking. Drilling in the melting Arctic is not compatible with this shift.”

This week I interviewed German climate expert Mojib Latif, who is being awarded a key European Environment prize for his tireless efforts to inform people about the risks of climate warming and the need to decarbonize the economy. His key message was that we have the technology to make a real difference. But it will only work if people take that to heart and don’t leave it up to the politicians, he says.

Shell’s departure from Alaska shows what “people power” can do.