Arctic sea ice, Greenland and Europe’s weird weather

As I write this, I am sitting in a short-sleeved shirt with the window open, enjoying an unusually warm start to the month of May. It’s around 27 degrees Celsius in this part of Germany, pleasant, but somewhat unusual at this time. The first four months of this year have been the hottest of any year on record, according to satellite data.

The Arctic is not the first place people tend to think of when it comes to explaining weather that is warmer – as opposed to colder – than usual in other parts of the globe. But several recent studies have increased the evidence that what is happening in the far North is playing a key role in creating unusual weather patterns further south – and that includes heat, at times.

Why sea ice matters

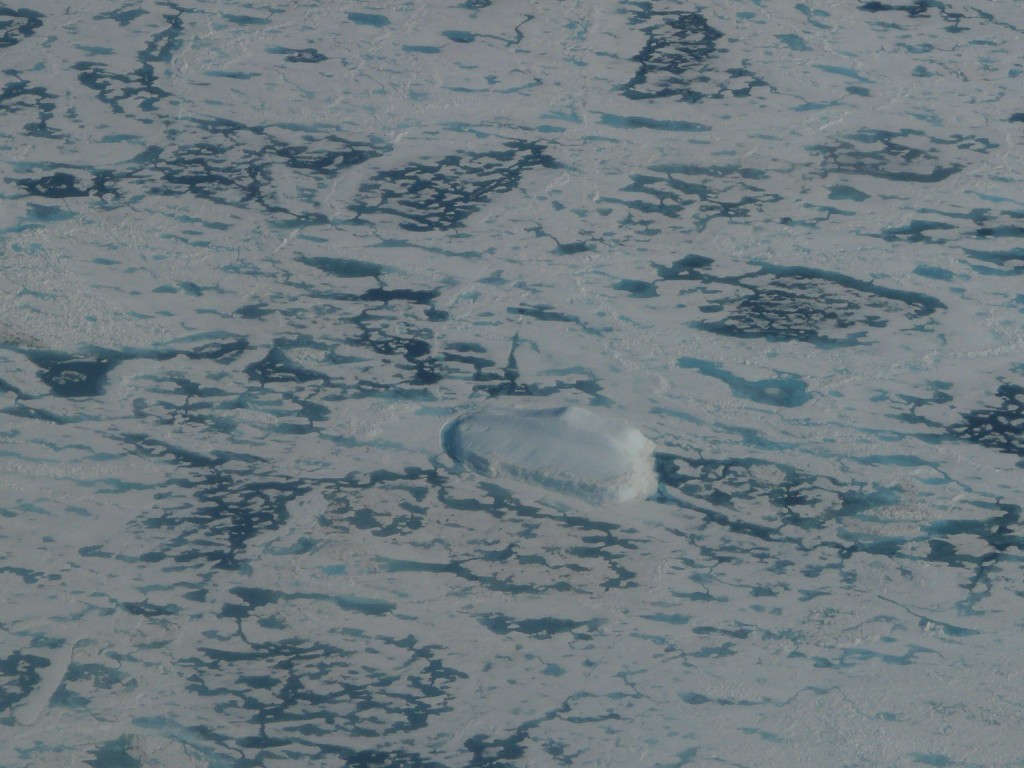

The Arctic has been known for a long time to be warming at least twice as fast as the earth as a whole. As discussed here on the Ice Blog, the past winter was a record one for the Arctic, including its sea ice. The winter sea ice cover reached a record low. Some scientists say the prerequisites are in place for 2016 to see the lowest sea ice extent ever.

Several recent studies have increased the evidence that these variations in the Arctic sea ice cover are strongly linked to the accelerating loss of Greenland’s land ice, and to extreme weather in North America an Europe.

“Has Arctic Sea Ice Loss Contributed to Increased Surface Melting of the Greenland Ice Sheet”, by Liu, Francis et.al, published in the journal of the American Meteorological Society, comes to the conclusion: “Reduced summer sea ice favors stronger and more frequent occurrences of blocking-high pressure events over Greenland.” The thesis is that the lack of summer sea ice (and resulting warming of the ocean, as the white cover which insulates it and reflects heat back into space disappears and is replaced by a darker surface that absorbs more heat) increases occurrences of high pressure systems which get “ stuck and act like a brick wall, “blocking” the weather from changing”, as Joe Romm puts it in an article on “Climate Progress”.

Everything is connected

The study abstract says the researchers found “a positive feedback between the variability in the extent of summer Arctic sea ice and melt area of the summer Greenland ice sheet, which affects the Greenland ice sheet mass balance”. As Romm sums it up:“that’s why we have been seeing both more blocking events over Greenland and faster ice melt.”

He quotes co-author Jennifer Francis of Rutgers University, New Jersey, explaining how these “blocks” can lead to additional surface melt on the Greenland ice sheet, as well as “persistent weather patterns both upstream (North America) and downstream (Europe) of the block.

“Persistent weather can result in extreme events, such as prolonged heat waves, flooding, and droughts, all of which have repeatedly reared their heads more frequently in recent years”, Romm concludes.

“Greenland melt linked to weird weather in Europe and USA” is the headline of an article by Catherine Jex in Science Nordic. People are usually interested in changes in the Greenland ice sheet because of its importance for global sea level, which could rise by around seven metres if it were to melt completely. But Jex also draws attention to the significance of changes to the Greenland ice for the Earth’s climate system as a whole.

The jet stream

“Some scientists think that we are already witnessing the effects of a warmer Arctic by way of changes to the polar jet stream. While an ice-free Arctic Ocean could have big impacts to weather throughout the US and Europe by the end of this century”.

She also notes some scientists warning of “superstorms”, if melt water from Greenland were eventually to shut down ocean circulation in the North Atlantic.

The site contains an interactive map to indicate how changes in Greenland and the Arctic could be driving changes in global climate and environment.

The jet streams drive weather systems in a west-east direction in the northern hemisphere. They are influenced by the difference in temperature between cold Arctic air and warmer mid-latitudes. With the Arctic warming faster than the rest of the planet, this temperature contrast is shrinking, and scientists say the jet streams are weakening.

Jex quotes meteorologist Michael Tjernström, from Stockholm University, Sweden: “Climatology of the last five years shows that the jet has weakened,” says. Its effect on weather around the world is a hot topic.

“We’ve had strange weather for a couple of years. But it’s difficult to say exactly why.”

One explanation, Jex writes, is that a weak jet stream meanders in great loops, which can bring extremes in either cold dry polar air or warmer wetter air from the south, depending on which side of the loop you find yourself. If the jet stream gets “stuck” in this kind of configuration, these extreme conditions can persist for days or even weeks.

Experts have attributed extreme events like the record cold on the east coast of the USA in early 2015, a record warm winter later the same year, and the summer heat waves and mild wet winters with exceptional flooding in the UK to these kind of “kinks” in the jet stream.

Greenland and the ocean

The changes to Greenland’s vast land ice sheet also have consequences for ocean circulation, because they mean an influx of the cold fresh water flowing into the salty sea. And the sea off the east coast of Greenland plays a key role in the movement of water, transporting heat to different parts of the world’s oceans and influencing atmospheric circulation and weather systems.

There have often been “catastrophe scenarios” suggesting the Gulf Steam, which brings warm water and weather from the tropics to the USA and Europe could ultimately be halted, leading to a new ice age. (Remember the “Day after Tomorrow?)

Although this extreme scenario is currently considered unlikely, research does suggest that the major influx of fresh water from melting ice in Greenland and other parts of the Arctic could slow the circulation and result in cooler temperatures in north western Europe.

Jex goes into the theory of a “cold blob” of ocean just south of Greenland, where melt water from the ice sheet accumulates. Some scientists say this indicates that ocean circulation is already slowing down. The “blob” appeared in global temperature maps in 2014. While the rest of the world saw record breaking warm temperatures, this patch of ocean remained unusually cold.

According to a recent study led by James Hansen, from Columbia University, USA, the ‘cold blob’ could become a permanent feature of the North Atlantic by the middle of this century. Hansen and his colleagues claim that a persistent ‘cold blob’ and a full shut down of North Atlantic Ocean circulation could lead to so-called ‘superstorms’ throughout the Atlantic. And there is geological evidence that this has happened before, they say. But the paper was controversial and many climate scientists questioned the strength of the evidence.

However, some scientists already attribute western Europe’s warm and wet winter of 2015 to the “cold blob”, Jex notes, which may have altered the strength and direction of storms via the jet stream.

The good old British weather

The UK’s Independent goes into a new study by researchers at Sheffield University, which indicates soaring temperatures in Greenland are causing storms and floods in Britain. The Independent’s author Ian Johnston says the study “provides further evidence climate change is already happening”.

It never ceases to amaze me that evidence is still being sought for that, but, clearly, there are still those who are yet to be convinced our human behavior is changing the world’s climate. So every bit of scientific evidence helps – especially if it relates to that all-time favourite topic of the weather.

The study also looks at the static areas of high pressure blocking the jet stream. With amazing temperature rises of up to ten degrees Celsius during winter on the west coast of Greenland in just two decades, it is not hard to imagine how this can effect the jet stream, and so our weather in the northern hemisphere.” If forced to go south, the jet stream picks up warm and wet air – and Britain can expect heavy rain and flooding. If forced north, the UK is likely to be hit by cold air from the Arctic”, Johnston writes.

The article quotes Professor Edward Hanna from the University of Sheffield, lead author of a paper about the research published in the International Journal of Climatology, and says seven of the strongest 11 blocking effects in the last 165 years had taken place since 2007, resulting in unusually wet weather in the UK in the summers of 2007 and 2012.

Hanna told the Independent computer models used 10 to 15 years ago to predict the extent of sea ice in the Arctic had significantly underestimated how quickly the region would warm.

“It’s very interesting to look at the observed changes in the Arctic … the actual observations are showing far more dramatic changes than the computer models,” Professor Hanna said.

“You do get sudden starts and jumps. It’s the sudden changes that can take us by surprise and there certainly does seem to have been an increase in extreme weather in certain places.”

Drawing conclusions (or not?)

In the Washington Post, (reprinted on Alaska Dispatch News) Chelsea Harvey sums up the conclusions of the latest research in an article entitled “Dominoes fall: Vanishing Arctic ice shifts jet stream, which melts Greenland glaciers”:

“There are a more complex set of variables affecting the ice sheet than experts had imagined. A recent set of scientific papers have proposed a critical connection between sharp declines in Arctic sea ice and changes in the atmosphere, which they say are not only affecting ice melt in Greenland, but also weather patterns all over the North Atlantic”.

So what do we learn from all of this? Sometimes I ask myself how many times we have to hear a message before we really take it in and decide to do something about it.

Here in Bonn, not far from the office where I am sitting now, the first round of UN climate talks since the Paris Agreement at the end of last year will be kicking off this coming weekend. The aim is to stop the rise in global temperature from going about two, preferably 1.5 degrees C. We have already passed the one degree mark. In an interview with the Guardian this week, the head of the IPCC Hoesung Lee says it is still possible to keep below two degrees, although the costs could be “phenomenal”. But many scientists and other experts are increasingly dubious about whether emissions can really peak in time to achieve the goal. Current commitments by countries to emissions reductions still leave us on the track for three degrees at least.

The concentration of greenhouse gases in the atmosphere is, as the Guardian puts it, “teetering on the brink of no return”, which the landmark 400 ppm measured for the first time at the Australian station at Cape Grim and unlikely to go below the mark again at the Mauna Loa station in Hawaii.

On my desk, I have a book entitled “Arctic Tipping Points”, by Carlos M. Duarte and Paul Wassmann. It was published in 2011. Before that, Professor Duarte had explained the global significance of what is happening in the Arctic to me

at an Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromso, Norway. How much more evidence do we need? Science takes a long time to research, evaluate and publish solid evidence of change and its consequences, with complex review processes. If politicians delay much longer, the pace of climate change will be so fast that action to avert the worst cannot keep up. Meanwhile, that Arctic ice keeps dwindling – and I sense another major storm on the approach.

Unbaking Alaska?

When I first went to Alaska in 2008, “Unbaking Alaska“ was the title of the reporting project on how climate change is affecting the region and what the world might be able to do about it. I had to explain the title to my German colleagues, unfamiliar with the “Baked Alaska” dessert, while my North American and British colleagues thought it was a quirky, witty little title.

This week, when I saw an article in the Washington Post entitled “As the Arctic roasts, Alaska bakes in one of its warmest winters ever”, I found the “dessert” had become a little stale .

The thing about “Baked Alaska” is that the ice cream stays cold inside its insulating layer of meringue. Unfortunately, all the information coming out of Alaska and the Arctic in general at the moment, suggest that the ice is definitely not staying frozen.

Too hot for comfort?

In the Washington Post article, Jason Samenow refers to this winter’s “shocking warmth” in the Arctic, some seven degrees above average. Alaska’s temperature, he says, has averaged about 10 degrees above normal, ranking third warmest in records that date back to 1925. Anchorage has found itself with a lack of snow.

“This year’s strong El Nino event, and the associated warmth of the Pacific ocean, is likely partly to blame, along with the cyclical Pacific Decadal Oscillation – which is in its warm phase”, Samenow writes. Lurking in the background is that CO2 we have been pumping out into the atmosphere over the last 100 years or so.

Sea ice on the wane?

Meanwhile, the Arctic sea ice is at a record low. Normally, in the Arctic, the ocean water keeps freezing through the entire winter, creating ice that reaches its maximum extent just before the melt starts in the spring. Not this time.

Yereth Rosen wrote on ADN on Feb. 24th the sea ice had stopped growing for two weeks as of Tuesday. He quotes the NSIDC as saying the ice hit a winter maximum on February 9th and has stalled since.

“If there is no more growth, the Feb. 9 total extent would be a double record that would mean an unprecedented head start on the annual melt season that runs until fall”.

This would be the earliest and the lowest maximum ever. Normally, the ice extent reaches its maximum in early or mid-March.

The most notable lack of winter ice has been near Svalbard, one of my own favourite, icy places.

The experts say it’s too early to say whether this is “it” for this season. There is probably more winter to come. But even if more ice is able to form, it will be very thin.

Toast or sorbet?

Coming back to those culinary clichés: Samenow in the Washington post writes of the second “straight toasty winter” in the “Last Frontier”. The links below his online article are listed under “more baked Alaska”. Amongst them I find the headline: “As Alaska burns, Anchorage sets new records for heat and lack of snow” and “Record heat roasts parts of Alaska”.

The trouble comes when these catchy titles become clichés and somehow stop being quirky.

Don’t we run the risk of not doing justice to the serious threat climate change is posing to the most fragile regions of our planet? Sometimes I worry that the warming of the Arctic is becoming something people take for granted, and, even more dangerous, something we can’t do much about. At times I sense a cynicism creeping in.

I for one will be keeping my oven-baked cake and chilled ice cream separate this weekend.

Is it possible to un-bake Alaska? Food for thought.

Picture gallery on “Baked Alaska” expedition.

“People power”, Shell and the Arctic

This week’s announcement that Shell is abandoning its controversial Arctic oil exploration for the “foreseeable future” provoked a wide spectrum of reactions – from disappointment, especially amongst politicians in Alaska, to the rejoicing of the environment campaigners.

Shell cites disappointing results, high operating costs – and an “unpredictable” regulatory environment as the reasons for the change in policy. The latter is the interesting one. Behind it lies an unmentioned but tangible ongoing shift in politics and society.

The tightening up of environment regulations in the USA is but one sign of the growing awareness that resources are limited, fossil fuels are harming the climate, and growth at the cost of environmental destruction is no longer acceptable.

Campaign success

Environment campaigners have run a highly visible and successful campaign drawing attention to the risks of oil drilling for one of the world’s last remaining pristine regions, which is also one of the most dangerous because of low temperature, ice and poor visibility.

Greenpeace has been campaigning online and around the globe to stop Arctic oil drilling. This summer, kayakers staged spectacular protests in Seattle against Shell’s Arctic drilling plans.

Critics have succeeded in increasing awareness of the paradox behind the increasing accessibility of the Arctic to oil and gas exploration. Warming through increased CO2 emissions from the burning of fossil fuels is melting the Arctic ice. Exploiting that harm humankind has done to the environment with a view to extracting more oil -which in turn would cause further damage to the climate and the planet we live on – is cynical at best, self-destructive at worst.

Reputation at stake

All this is harmful to the image of Royal Dutch Shell. The Guardian quotes Greenpeace Arctic campaigner Ben Ayliffe:

“It is undeniable that the protests were a factor in Shell’s decision because the Arctic had become a defining environmental story”.

The paper quotes “company sources” as accepting that Arctic oil damaged the firm. “We were acutely aware of the reputational element to this programme”.

Shell had invested around seven billion US dollars in its Alaskan operations. But investors are worried about whether the company’s business models can hold against international climate protection goals.

Not the last word

The decision does not mean Shell will stay out of the region for good. Nor is it the end of oil exploration in the Arctic in general. BP’s Prudhoe Bay field and Gazprom’s Prirazlomnoye platform in the Pechora Sea – the object of the spectacular Greenpeace protests and Russian seizure of the organization’s boat and crew in 2013 – remain.

Nevertheless, Shell’s decision has to be a milestone in the ongoing struggle to protect the environment and halt climate change through a switch to renewable energies. Greenpeace International Executive Director Kumi Naidoo told journalists:

“It’s time to make the Arctic ocean off limits to all oil companies. This may be the best chance we get to create permanent protection for the Arctic and make the switch to renewable energy instead. If we are serious about dealing with climate change we will need to completely change our current way of thinking. Drilling in the melting Arctic is not compatible with this shift.”

This week I interviewed German climate expert Mojib Latif, who is being awarded a key European Environment prize for his tireless efforts to inform people about the risks of climate warming and the need to decarbonize the economy. His key message was that we have the technology to make a real difference. But it will only work if people take that to heart and don’t leave it up to the politicians, he says.

Shell’s departure from Alaska shows what “people power” can do.

Arctic oil – still in the picture

Was it too good to be true? The euphoria over the US administration’s moves to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was dampened somewhat when, just two days later, it released a long-term plan for opening coastal waters to oil and gas exploration, including areas in the Arctic off Alaska. The plan excludes some important ecological and subsistence areas from potential drilling, but it still includes some Arctic areas, including parts of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

Margaret Williams, managing director of WWF US Arctic Programs, told Deutsche Welle, she welcomed in particular the decision to protect the biological hotspot of Hanna Shoal from risky offshore drilling. The Hanna Shoal is a key site for walruses and other animals.

But she stressed other areas of the US Arctic were still subject to oil exploration. The new program will not affect existing leases held by Shell in the Chukchi Sea. The company’s efforts have been the subject of controversy, not least since the grounding of the drill rig Kulluk.

Williams says the problem with the new proposal in general is that it “keeps drilling for oil in the US Arctic offshore in the picture”. With the US poised to take the helm of the Arctic Council, she called for protecting biodiversity to be a top priority for all Arctic nations.

Oil: valuable asset or liability?

It comes as no surprise that Alaskan state politicians and the oil industry promised to fight planned restrictions, saying they were harmful to the economy. But this brings us back to the question of whether the search for new oil in the Arctic makes any sense at all at a time when oil prices are at a record low and the USA is producing plentiful supplies of shale gas.

Bloomberg financial news group quotes financial experts as saying the world’s biggest oil producers do not have “bulletproof business models”, and cites financial cutbacks by BP, Chevrol and Shell:

“The price collapse hobbles a segment of the industry that had already been struggling with years of soaring construction costs, project delays, missed output targets and depressed returns from refining crude into fuels”, analyst Anish Kapadia told Bloomberg.

Climate paradox

Conservation groups stressed the need for a different focus, in the year when the USA has pledged to help create an effective new world climate agreement in Paris in November.

Cartoon by psychologist Per Espen Stoknes, BI Norwegian School of Management.( I photographed it at a workshop on climate change psyschology)

“Rather than opening more of the Arctic and other US coastal waters to drilling for dirty energy, the US needs to ramp-up its transition to a clean energy future. As the Administration works to rally international leaders behind a bold climate pact in 2015, decisions to tap new fossil fuel reserves off our own coasts sends mixed signals about US climate leadership abroad, ” said WWF’s Williams.

We know the Arctic is being hit at least twice as fast as the global average by climate change. The ecosystem is already under huge pressure. The Arctic itself is in turn of key importance to global weather patterns. And burning more oil would exacerbate the situation even further.

“We would like to think that we can shift our energy paradigm to clean energy so that we don’t have to take every last bit of oil out of the earth, especially out of the oceans”, said Jackie Savitz from the Oceana Campaign croup.

Studies by the group and by WWF indicate that developing renewable energy technologies such as offshore wind could create more jobs than hanging on to fossil fuel technologies.

Oil spill concern

In addition to the climate paradox of the hunt for new fossil fuels, environmentalists are concerned about the possible impact of an oil spill. Their opposition is not limited to the Arctic. Proposals to open up large areas of coastal waters including some parts of the Atlantic for the first time have also aroused anxiety about possible pollution. But the Arctic is of particular concern because of its remoteness, harsh weather conditions and seasonal ice cover, which is not likely to disappear soon even with rapid climate change:

“Encouraging further oil exploration in this harsh, unpredictable environment at a time when oil companies have no way of cleaning up spills threatens the health of our oceans and local communities they support. When the Deepwater Horizon spilled 210 million gallons of crude oil five years ago, local wildlife, communities and economies were decimated. We cannot allow that to happen in the Arctic or anywhere else,” said WWF expert Williams.

White House senior counsellor John Podesta justified the ban on oil exploration in the ANWR by saying “unfortunately accidents and spills can still happen, and the environmental impacts can sometimes be felt for many years”. The question is – why should this only be applicable in certain areas? Campaigners say it also applies to the other areas now designated by the administration as “OK” for exploration. For the Arctic in particular, limiting exploration to remote offshore areas does not protect the region against the risk of environmental disaster.

Obama stops oil in Arctic Wildlife Reserve

Back in Germany after spending a week and a half on the RV Helmer Hanssen off the coast of Spitsbergen, and then in Norway’s Arctic capital Tromso at Arctic Frontiers, I thought I might be in for a shock on my return to warmer climes and a news agenda focusing on stories non-Arctic. Instead, I found some continuity both in the weather and the media. A heavy fall of snow here kept the Arctic feeling alive, while a twitter of messages on Sunday carried on the lively debate that was happening at Arctic Frontiers over the pros and cons of oil drilling in the Arctic.

The Washington Post broke the story about President Obama proposing new wilderness protection in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). “Alaska Republicans declare war” was the second part of the headline. Clearly, emotions are running high.

The Obama administration is proposing setting aside more than 12 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska as wilderness. This stops – at least for the moment – any prospect of oil exploration in an area which has long been the subject of controversy between those who say environment protection should be the number one priority and those who say finding oil is more important.

“Alaska’s National Wildlife Refuge is an incredible place – pristine, undisturbed. It supports caribou and polar bears, all manner of marine life, countless species of birds and fish, and for centuries it supported many Alaska Native communities. But it’s very fragile”, the President says in a White House video about the proposals.

It seems this is only the first of a series of decisions to be made by the Interior Department relating to the state’s oil and gas production during the coming week. The Washington Post says the department will also put part of the Arctic Ocean off limits to drilling, and is considering whether to impose additional limits on oil and gas production in parts of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska.

Only the US Congress can actually create a wilderness area, but once the federal government has designated a place for that status, it receives the highest level of protection until Congress acts. “The move marks the latest instance of Obama’s aggressive use of executive authority to advance his top policy priorities”, writes Juliet Eilperin in the Washington Post.

The ANWR holds considerable reserves of petroleum, but is also a critical habitat for Arctic wildlife. Senator Lisa Murkowski from Alaska is the new chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Unsurprisingly, she is set to fight the Obama decision. The Governor of Alaska, Bill Walker, issued a statement saying he might have to accelerate giving permits for oil and gas on state lands to compensate for the new federal restrictions.

Can the fate of an area of such key ecological importance really be reduced to a good to be bargained for in a political tit-for-tat?

Conservation groups were over the moon about the Obama move. “Some places are simply too special to drill, and we are thrilled that a federal agency has acknowledged that the refuge merits wilderness protection”, said a statement from Jamie Williams, president of the Wilderness Society.

But apart from the danger of an oil spill and the threat to the habitat of Arctic species, we have to come back to that Tromso conference theme of Climate and Energy. The Arctic is being hit at least twice as fast as the global average by climate change. The ecosystem is already under huge pressure. The Arctic itself is of key importance to global weather patterns. And burning more oil would exacerbate the situation even further. I am reminded of the argument put forward by Jens Ulltveit-Moe, the CEO of Umoe, himself a former oil industry executive. Apart from the fact that the current low oil price means the Arctic oil hunt is too expensive, if the world is serious about emission cuts to halt climate warming, there is no need for and will be no demand for oil from the Arctic in coming decades.

That is something to be kept in mind as the debate in the USA continues over that precious piece of land and sea that is the ANWR.

Feedback