117 Search Results for: Quaile

“Last Ice” claims lives of researchers

This post was to be about a trip I just made to St. Petersburg to talk to students and fellow journalists about reporting climate change. Instead, I am shocked and saddened to be writing of the apparent loss of one of the people whose work featured prominently in my talks there. Polar explorer and researcher Marc Cornelissen, who led our Alaskan Arctic expedition in 2008, the first to be documented on the fledgling “Ice Blog”, disappeared in the Canadian Arctic this week and is presumed drowned after breaking through unseasonably thin ice.

In workshops and discussion panels in St. Petersburg, I found myself recounting, as I often seem to do, some of my experiences during that trip. This was the expedition which strengthened my conviction that reporting on climate change in the polar regions and its relevance for the whole world had to be a main focus of my work in coming years. I have been in the Arctic many times, but somehow that trip seems to be the one I always come back to. Dutch polar explorer and researcher Cornelissen was taking a group of young Europeans to Arctic Alaska, to find out how scientists measure sea ice thickness and other parameters – and how climate change was affecting the local indigenous population. In a talk last week, while I told students and environment journalists in St. Petersburg how that group of young Europeans found out about climate change first-hand during the “Climate Change College” project, I was unaware that the charismatic leader of that trip would not be returning from his latest Arctic expedition.

Marc Cornelissen shows climate ambassadors how to drill to measure ice thickness (i.Quaile, Alaska, 2008)

“Search and rescue” becomes “recovery”

Back in Germany I opened my Ipad one morning this week to find urgent messages from two friends I first met during that Alaskan trip – one in the USA, one in Europe – telling me Marc and his colleague Philip de Roo had gone missing on their latest climate fact-finding mission in the Canadian High Arctic. Since then, the search and rescue operation has been called off, the two researchers presumed drowned.

Marc, founder of the organisation Cold Facts, which supports scientific research in polar areas, was travelling on skis with his colleague, for a mission called the “Last Ice Survey“. That title was to become tragically apt in a way they had not anticipated. The two were measuring the thickness of the ice in the “Last Ice Area”,, which is thought to be the place where summer sea ice will continue longest as climate change progresses.

Arctic conditions “tropical”

In his last audio message, sent on April 28th, Marc Cornelissen, always with a great sense of humour, recounts how the weather had been so hot he had to ski in his underpants. He talks of thin ice ahead, and of the likely need to alter course to avoid it.

“We think we see thin ice in front of us, which is quite interesting, and we’re going to research some of that if we can”, Marc said in the last voice mail. Tragically, it seems that research was to prove fatal for the two curious travellers.

Next day the Royal Canadian Mounted Police in Resolute Bay was alerted by a distress signal from the pair, approximately 200 kilometres soiuth of Bathurst Island. The search aircraft sighted one of their sleds, partly unpacked, on the ice with their sled dog, close to a hole in the ice. The other sled was in the water with various bits of equipment.The search and rescue venture was eventually abandoned. The dog has been rescued, but the operation to locate Marc, Philip and their equipment and bring it home, has been halted by bad weather.

The remote, cold, Arctic is a risky place to travel at the best of times. Cornelissen and de Roo were experienced polar explorers. They knew the risks. What they presumably did not know, was just how thin that “last ice” had become.

Cornelissen’s team drills to measure methane emissions from melting permafrost (I.Quaile, Denali, 2008)

Climate change is affecting the Arctic faster than any other area of the world. That was the message behind the work of the two researchers . Perhaps it was changing faster than they could have imagined.

Beautiful, fragile, perilous

I am deeply moved by the loss of these two talented and committed fellow Arctic-enthusiasts, who would still have had so much to offer the world. How ironic that the rapid ice melt they were out to document was, it seems, to claim their lives. How sad if these two had to die to underline the point.

A year and a half ago, I narrowly escaped with my life when I slipped off an icy mountain ledge in the alps. Since then, I have been more keenly aware than ever of that ambivalent nature of ice – the attraction of its beauty and the unpredictable dangers. I remember the feeling “this cannot be happening to me”, as I thought the ice I loved was throwing me to my death. I am somehow haunted by images of what Marc and Philip might have sensed in those final, precarious moments in their beloved Arctic.

Marc Cornelissen was a charismatic character, full of stories and enthusiasm for the polar regions. I remember how we laughed as he told us the tale of the “polar bear that caught me with my pants down”, during one of his expeditions. But humour and positive outlook never detracted from his concern for the safety and well-being of his charges, as he guided them onto the sea ice or frozen Arctic lakes. Cornelissen was also a motivating guide and mentor to many who have gone on to make their professions in the fields of climate, environment and sustainability.

He also had an unerring sense of the issues that would emerge ever larger in the polar climate debate in the years to come: sea ice melt, coastal erosion, melting permafrost, methane emissions.

“Everything is connected”.

Why is it I always come back to that particular Arctic trip? It is partly because it was an encounter between commited, idealistic, prosperous young Europeans, with their first climate-saving projects already in the bag, and the “locals” of Barrow, the northernmost – and so very different – settlement in the USA. These were a mixture of Inupiat traditional whale-hunters, who depended on stable sea ice to hunt – and oil workers, who owed their livelihood to the fossil fuels which are helping to melt it.

“Everything is connected” was the conclusion that dawned on the young Danish member of the group, as we stood by a visitors’ centre to look at glaciers further south – which had retreated so far, they were no longer visible from that point.

Irish “climate ambassador” Cara Augustenborg, posted her own moving tribute to Cornelissen earlier this week.

The network that was born during that Alaskan trip is still thriving. The climate ambassadors have gone on to make their ways and play their parts in the effort to understand the workings of the planet and create a low-carbon future.

For all that, you need inspiring leaders, and people who are not afraid to take on the risks of the remote, icy, unpredictable and rapidly changing Arctic. In the last personal message I got from Marc Cornelissen, he had been looking at the Ice Blog and said how pleased he was that I had “stayed with the Arctic”. Me too, Marc. And I am sorry I will never be able to interview him on what seems to have been his final expedition to the “Last Ice”.

Ice paradoxes from pole to pole

Returning after a longish break with little access to news and data, there are several ice and snow stories jumping out of my mailbox at me. I’ve picked out two which those of a skeptical persuasion might say disprove some key climate assumptions, but which actually, in fact, confirm some trends and predictions.

Worrying, but not unexpected, are the latest measurements of the extent of the Arctic sea ice. In February, the experts at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) based in Boulder, Colorado, noted a record for the lowest observed maximum sea ice extent. Although it seems the sea ice did grow at some points during March, the overall for the month was the lowest recorded since satellite measurements began in 1979. The average extent for the month was 14.39 million square km – some 1.13 million square km below the 1981-2010 long-term average. The previous March low of 14.45 million square km was recorded in 2006.

In the Arctic Journal, Kevin McGwin quotes Andy Mahoney, a geophycisist with the Sea Ice Group at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, as saying the irregular pattern, with a kind of “double dip”, with the ice decreasing, increasing, then decreasing again, is “a pretty unusual event, regardless of the reason”. Normally, the ice levels would increase to the seasonal maximum first in March, then decline.

One reason, Mahoney says, could be the wind blowing ice into the regions where ice growth was observed, according to the NDSIC the Bering Sea, Davis Strait and around Labrador.

No contradiction to climate warming theory

The NSDIC says warm conditions in the Bering Sea and the Russian Sea of Okhotsk contributed to the record low winter ice maximum.

The overall downward trajectory, however, is clear. The brief increase in March is not a sign that the sea ice is recovering. Mahoney told the Arctic Journal parts of Alaska had seen abnormally high temperatures this winter, which was in line with the overall seasonal ice observations.

“What drives the maximum extent is what happens at the margins, and they can grow and retreat due to short-term variants. The conditions in the central Arctic, far from the action, are indicative of the warm year we’ve had in Alaska,” he said. Barrow, on Alaska’s northern coast, far away from the southern margin, for example, saw a lot of broken ice this winter, according to Maloney.

WWF expressed concerned about the latest figures:

“This is not a record to be proud of. Low sea ice can create a series of reactions that further threaten the Arctic and the rest of the globe,” said Alexander Shestakov, Director, WWF Global Arctic Programme.

“This chilling news from the Arctic should be a wakeup call for all of us,” said Samantha Smith, the leader of WWF’s Global Climate and Energy Initiative. She stresses the need to cut global emissions to halt the Arctic melt.

The proportion of thick Arctic ice that lasts multiple years has dwindled over the past two decades. A recent study shows that Arctic sea ice has thinned by 65 per cent since 1975, leaving ice that is more susceptible to melting.

Writing for Alaska Dispatch News (AND), Yereth Rosen notes that the most dramatic changes in the Arctic sea ice extent have been in the melt season, not in the period of maximum winter coverage. He quotes NSIDC scientist Julienne Strove, who led a study published last year in Geophysical Research Letters which showed the open-water season is lengthening, mostly because of extended melt in summer and autumn. So is this additional winter record a sign of more melting to come? Only time will tell, but the signs are not looking good.

Warmer temperatures, more snow? Belgian International Polar Foundation shot of director and explorer Alain Hubert in the Antarctic.

A story from the opposite pole has also attracted attention. It says climate change is actually increasing the amount of snow in the Antarctic. Puzzling? Not necessarily.

More heat, more snow?

An international study headed by Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research (PIK) comes to the conclusion that every degree of regional warming could increase snowfall there by around five percent. The estimate is based on ice cores and climate modeling.

The information adds a new element to calculations of how much the Antarctic will contribute to global sea level rise. Some people might assume more snow would stop the Antarctic from losing mass. In fact the increasing weight of new snow and ice can make it slide towards the coast and into the ocean faster. In this connection, you might like to read some more stories on these Antarctic issues:

Thicker-ice-in-the-antarctic-good-news-for-the-climate?

Antarctic melt could raise sea levels faster

West Antarctic ice sheet collapse unstoppable

Anders Levermann, one of the new study authors, whom I have spoken to several times on the effects of climate change on the Antarctic and global sea levels, says the latest results back up earlier conclusions that the Antarctic will lose more ice than it will gain and thus have a major influence on global sea level. Levermann, from PIK, is also one of the lead authors of the sea-level chapter of the IPCC report. He stresses that the latest study just provides yet another piece of the “jigsaw puzzle” coming together on how global sea level is likely to develop in the future.

If the world leaders called on to come up with a new world climate agreement at the end of this year need any more motivation, this scientific research from both ends of the world should really give them an extra push.

Sharing Arctic ocean data

This week I had an interesting conversation with Professor Karen Wiltshire, who is deputy director of Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research. Last time I talked to Karen was on the German North Sea Island of Helgoland, where she is also head of AWI’s Biological Institute. “Jellyfish and chips” is the theme of the article I wrote then about the institute’s research into the impacts of climate change on the North Sea. Tasty?

This time, I was interviewing her on a wider issue, which also has direct relevance to the Arctic. She has taken over the chair of the “Partnership for Observation of the Global Oceans”, or POGO for short, for the next two years. The Directors of the group just had their annual meeting in Tenerife, on the Canary Islands. POGO, Karen told me, is one of the oldest international organizations set up to link partners interested in observing the world’s oceans. It includes all the world’s key marine institutes, including AWI, Woods Hole, Scripps and institutes from China, Korea and Russia.

The directors meet once a year to discuss issues which can be tackled in a coordinated manner. This includes things like research vessels and monitoring marine protected areas.

Exchanging Arctic Data

But one issue which could bring a lot of benefits in particular to scientists working on the Arctic, is the decision taken at the Tenerife meeting to set up a new platform to link up all the long-term ocean data sets in the world. At the moment, Professor Wiltshire says scientists often don’t know of the existence of a lot of data:

“Some of it is very high quality. For example in northern Russia, in the Arctic Ocean, there’s a lot of data that’s not so easily accessible and available. But if our Russian partners just put a flag on the map saying we have this data, and you can come to us if you need it, it would already help us scientists a lot.

“It’s kind of like making a giant inventory of what’s out there, and of what has been measured for the last hundred years. The next step would be to link important oceans with one another, the Arctic and the Atlantic, and look how they have changed relative to one another, and set up hydrographic models linking these oceans. Those models already exist, but with a better data base we might be able to check the rigor of these models, also relative to the melting ice caps. So the first step is to inventorize what’s out there, and then link data sets, variables and ocean areas.”

Russian data is key

This brings me back to conversations I had on my recent Arctic expedition on the RV Helmer Hanssen. Stig Falk-Petersen, the cruise leader, from Norway’s Arctic University of Tromso, stressed to me just how much research on the Arctic has actually been conducted by Russian scientists. In the past, this was rarely translated, so not available to the majority of the international research community. Things have changed since the end of the Soviet Union, Stig told me, and it became easier for western scientists to work with their Russian colleagues.

“And what we discovered then, was that the Russians know all about our famous polar explorers Nansen and Amundsen, but we new nothing about the Russians. Yet the Russians have a fantastic record of science in the Arctic. Since 1937 they have had these drifting stations, they flew out from Novaya Zemlya and landed on North Pole with four engines, Antonov planes, and established an ice camp. And they drifted out the Fram Strait. They have done this nearly every year until recently. So all we know about the Arctic , the topography, situation of water masses, animal life, benthic life, is actually based on Russian expeditions. And this is still poorly known in the west.”

Modern ice drift

Stig is a great fan of a current drift venture, the Fram 2013-2014 expedition, which is more or less repeating that of the first Russian drift station.

The Norwegian scientists Yngve Kristoffersen and Audun Tholfsen are living and working on their ice drift station, including the hovercraft “Sabvabaa”. It was taken and placed on the ice by the AWI’s research vessel the Polarstern, demonstrating once more the benefits of international cooperation in science. The two men have been taking sediment cores to learn about the polar environment more than 60 million years ago. Since August 2014 they have moved northwards along the submarine Lomonosov Ridge. You can follow their progress online at Geonova. Let me just quote a little from their latest diary:

“The length of Lomonosov Ridge ( ̴1.800 km) is roughly equal to the length of Norway. We have now spent 5 months drifting over the Lomonosov Ridge and been able to get new scientific data over a section which constitutes 1/4 of the total length of the ridge. Our drift shows a pattern with periods of very slow ice drift interrupted by events of fast drift. The fast drift is forced by cells of low surface air pressure moving in to the Arctic Ocean over the Canadian Arctic Islands as lately or through the Fram Strait. As they move in, the wind direction drives the ice to the west. These events, unpredictable on a time scale of months, make it impossible to estimate with some degree of confidence where we will be when it is time for Audun to rotate off in late March/April or when we will approach the ice edge in the Fram Strait.”

The data recorded by the scientists is transferred automatically to the Nansen Centre in Bergen. Stig tells me it includes some spectacular underwater videos going right down to the sea bottom, 2000 metres. He and his colleagues are eagerly awaiting a look at the data.

Data from polar orbit satellites is received and processed at KSAT in Tromso. I was able to visit in January. (Pic. I Quaile)

These days, modern technology, from satellite monitoring to a network of buoys moored around the world’s oceans, some with remote data transmission, provide an increasing amount of new data to be shared and analysed. But to understand properly how the oceans are changing, we need data from the past to compare it with. This brings me back to my interview with Karen Wiltshire.

I asked her whether there wasn‘t a danger that research is not able to keep up with the speed of change? Here is her answer:

“There’s very much the danger of that. One of the most important things is having consistent long-term observation. We need to link up old observations, be it whether somebody stood at the end of a dock and measured salinity for a time, in the late 1800s or so, through to now, where we have modern ways of measuring. These things need to be linked and compared to each other to find out whether what you are looking at is related to a real trend or shift, or is just an anomaly in the system. One has to be very mathematically oriented and creative in doing so. Very often, for example in the Wadden Sea, (off the coasts of Germany, Denmark and the Netherlands), we even use historical anecdotes written down in the annals of churches, for example, to look at how the weather was at a certain time, whether we had an ice winter or not. The more information we have from the past, the better it is. Then we’re in a better position to interpret modern-day data, which might be of very short duration in comparison to the long sets of data out there.”

So the new project to link the world’s oceanic data could be a very important step forward. Here’s to success for the latest POGO venture!

You can listen to the interview with Karen Wiltshire on this week’s Living Planet programme, or by itself here.

Arctic oil – still in the picture

Was it too good to be true? The euphoria over the US administration’s moves to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was dampened somewhat when, just two days later, it released a long-term plan for opening coastal waters to oil and gas exploration, including areas in the Arctic off Alaska. The plan excludes some important ecological and subsistence areas from potential drilling, but it still includes some Arctic areas, including parts of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

Margaret Williams, managing director of WWF US Arctic Programs, told Deutsche Welle, she welcomed in particular the decision to protect the biological hotspot of Hanna Shoal from risky offshore drilling. The Hanna Shoal is a key site for walruses and other animals.

But she stressed other areas of the US Arctic were still subject to oil exploration. The new program will not affect existing leases held by Shell in the Chukchi Sea. The company’s efforts have been the subject of controversy, not least since the grounding of the drill rig Kulluk.

Williams says the problem with the new proposal in general is that it “keeps drilling for oil in the US Arctic offshore in the picture”. With the US poised to take the helm of the Arctic Council, she called for protecting biodiversity to be a top priority for all Arctic nations.

Oil: valuable asset or liability?

It comes as no surprise that Alaskan state politicians and the oil industry promised to fight planned restrictions, saying they were harmful to the economy. But this brings us back to the question of whether the search for new oil in the Arctic makes any sense at all at a time when oil prices are at a record low and the USA is producing plentiful supplies of shale gas.

Bloomberg financial news group quotes financial experts as saying the world’s biggest oil producers do not have “bulletproof business models”, and cites financial cutbacks by BP, Chevrol and Shell:

“The price collapse hobbles a segment of the industry that had already been struggling with years of soaring construction costs, project delays, missed output targets and depressed returns from refining crude into fuels”, analyst Anish Kapadia told Bloomberg.

Climate paradox

Conservation groups stressed the need for a different focus, in the year when the USA has pledged to help create an effective new world climate agreement in Paris in November.

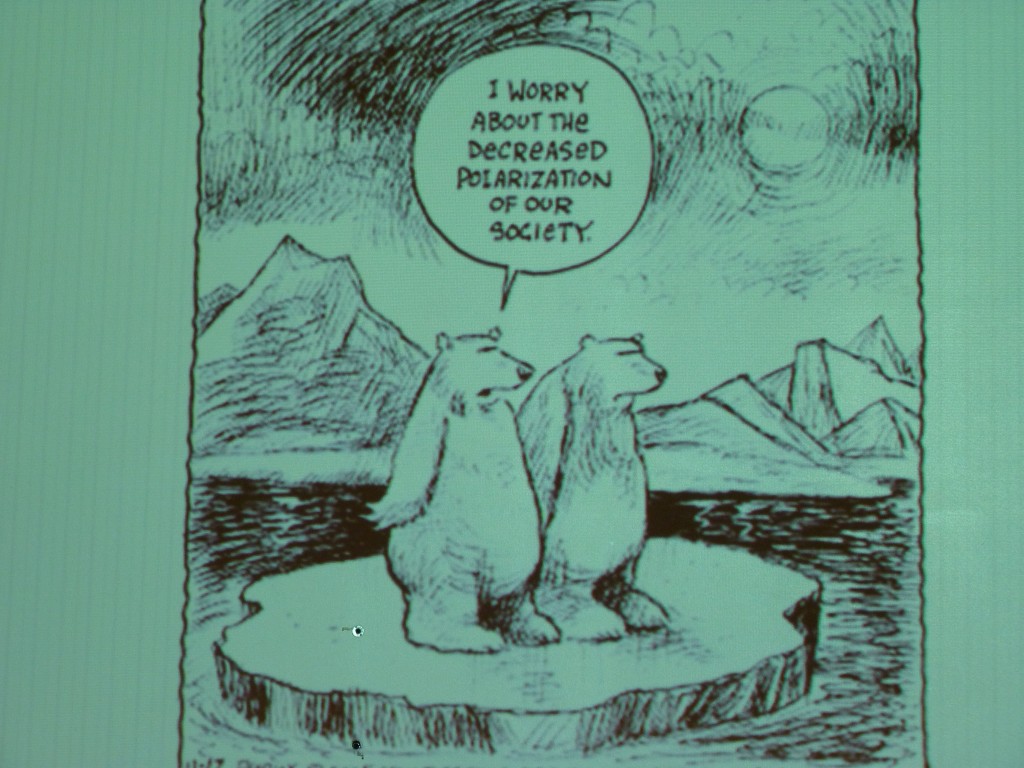

Cartoon by psychologist Per Espen Stoknes, BI Norwegian School of Management.( I photographed it at a workshop on climate change psyschology)

“Rather than opening more of the Arctic and other US coastal waters to drilling for dirty energy, the US needs to ramp-up its transition to a clean energy future. As the Administration works to rally international leaders behind a bold climate pact in 2015, decisions to tap new fossil fuel reserves off our own coasts sends mixed signals about US climate leadership abroad, ” said WWF’s Williams.

We know the Arctic is being hit at least twice as fast as the global average by climate change. The ecosystem is already under huge pressure. The Arctic itself is in turn of key importance to global weather patterns. And burning more oil would exacerbate the situation even further.

“We would like to think that we can shift our energy paradigm to clean energy so that we don’t have to take every last bit of oil out of the earth, especially out of the oceans”, said Jackie Savitz from the Oceana Campaign croup.

Studies by the group and by WWF indicate that developing renewable energy technologies such as offshore wind could create more jobs than hanging on to fossil fuel technologies.

Oil spill concern

In addition to the climate paradox of the hunt for new fossil fuels, environmentalists are concerned about the possible impact of an oil spill. Their opposition is not limited to the Arctic. Proposals to open up large areas of coastal waters including some parts of the Atlantic for the first time have also aroused anxiety about possible pollution. But the Arctic is of particular concern because of its remoteness, harsh weather conditions and seasonal ice cover, which is not likely to disappear soon even with rapid climate change:

“Encouraging further oil exploration in this harsh, unpredictable environment at a time when oil companies have no way of cleaning up spills threatens the health of our oceans and local communities they support. When the Deepwater Horizon spilled 210 million gallons of crude oil five years ago, local wildlife, communities and economies were decimated. We cannot allow that to happen in the Arctic or anywhere else,” said WWF expert Williams.

White House senior counsellor John Podesta justified the ban on oil exploration in the ANWR by saying “unfortunately accidents and spills can still happen, and the environmental impacts can sometimes be felt for many years”. The question is – why should this only be applicable in certain areas? Campaigners say it also applies to the other areas now designated by the administration as “OK” for exploration. For the Arctic in particular, limiting exploration to remote offshore areas does not protect the region against the risk of environmental disaster.

Obama stops oil in Arctic Wildlife Reserve

Back in Germany after spending a week and a half on the RV Helmer Hanssen off the coast of Spitsbergen, and then in Norway’s Arctic capital Tromso at Arctic Frontiers, I thought I might be in for a shock on my return to warmer climes and a news agenda focusing on stories non-Arctic. Instead, I found some continuity both in the weather and the media. A heavy fall of snow here kept the Arctic feeling alive, while a twitter of messages on Sunday carried on the lively debate that was happening at Arctic Frontiers over the pros and cons of oil drilling in the Arctic.

The Washington Post broke the story about President Obama proposing new wilderness protection in the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge (ANWR). “Alaska Republicans declare war” was the second part of the headline. Clearly, emotions are running high.

The Obama administration is proposing setting aside more than 12 million acres of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge in Alaska as wilderness. This stops – at least for the moment – any prospect of oil exploration in an area which has long been the subject of controversy between those who say environment protection should be the number one priority and those who say finding oil is more important.

“Alaska’s National Wildlife Refuge is an incredible place – pristine, undisturbed. It supports caribou and polar bears, all manner of marine life, countless species of birds and fish, and for centuries it supported many Alaska Native communities. But it’s very fragile”, the President says in a White House video about the proposals.

It seems this is only the first of a series of decisions to be made by the Interior Department relating to the state’s oil and gas production during the coming week. The Washington Post says the department will also put part of the Arctic Ocean off limits to drilling, and is considering whether to impose additional limits on oil and gas production in parts of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska.

Only the US Congress can actually create a wilderness area, but once the federal government has designated a place for that status, it receives the highest level of protection until Congress acts. “The move marks the latest instance of Obama’s aggressive use of executive authority to advance his top policy priorities”, writes Juliet Eilperin in the Washington Post.

The ANWR holds considerable reserves of petroleum, but is also a critical habitat for Arctic wildlife. Senator Lisa Murkowski from Alaska is the new chairman of the Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee. Unsurprisingly, she is set to fight the Obama decision. The Governor of Alaska, Bill Walker, issued a statement saying he might have to accelerate giving permits for oil and gas on state lands to compensate for the new federal restrictions.

Can the fate of an area of such key ecological importance really be reduced to a good to be bargained for in a political tit-for-tat?

Conservation groups were over the moon about the Obama move. “Some places are simply too special to drill, and we are thrilled that a federal agency has acknowledged that the refuge merits wilderness protection”, said a statement from Jamie Williams, president of the Wilderness Society.

But apart from the danger of an oil spill and the threat to the habitat of Arctic species, we have to come back to that Tromso conference theme of Climate and Energy. The Arctic is being hit at least twice as fast as the global average by climate change. The ecosystem is already under huge pressure. The Arctic itself is of key importance to global weather patterns. And burning more oil would exacerbate the situation even further. I am reminded of the argument put forward by Jens Ulltveit-Moe, the CEO of Umoe, himself a former oil industry executive. Apart from the fact that the current low oil price means the Arctic oil hunt is too expensive, if the world is serious about emission cuts to halt climate warming, there is no need for and will be no demand for oil from the Arctic in coming decades.

That is something to be kept in mind as the debate in the USA continues over that precious piece of land and sea that is the ANWR.

Feedback