Search Results for Tag: Antarctic

Polar ice tipping points

As I get ready to head up to Tromso for the Arctic Frontiers conference and prepare my accreditation for the next routine round of climate talks here in Bonn in March, I find myself with plenty of food for thought.

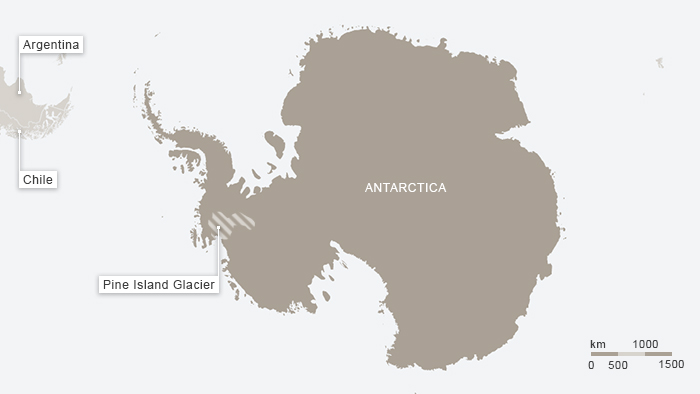

It seems like not that long ago that scientists were telling us that although the Arctic is clearly melting fast, there was no need to worry about the Antarctic ice melting. But for the past 15 years or so, scientists have been observing that glaciers in West Antarctica are out of balance. Ice shelves have been breaking off and the calving fronts of glaciers have been retreating, draining huge amounts of ice into the ocean. This week I was interested and concerned to read about the results of a modelling effort, using 3 different types of model, indicating a key Antarctic glacier was melting irreversibly.

(Map courtesy of Deutsche Welle)

The Pine Island Glacier in the Antarctic hit the headlines last year when a giant iceberg broke off it. It is a key glacier because it is actually responsible for some 20 percent of the total ice loss from the region. Now scientists have found the glacier is melting irreversibly – with dramatic consequences for global sea levels. For an article for DW entitled Antarctic’s glacier retreat unstoppable, I interviewed Gael Durand of the French University of Grenoble, one of a team of scientists who have just published the new study: “We show that the Pine Island Glacier will continue to retreat and that this retreat is self-sustaining. That means it is no longer dictated by changes in the ocean or the atmosphere, but is an internal, dynamic process”, Durand told me. This will mean an increasing discharge of ice and a greater contribution to global sea level rise. “It was estimated at around 20 gigatons per year during the last decade, and that will probably increase by a factor of three or five in the coming decade. That means this glacier alone should contribute to the sea level by 3.5 to 10 millimetres a year, accumulating to up to one centimetre sea rise over the next 20 years. For one glacier, that is colossal”, says Durand.

I called up Angelika Humbert from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) to get an expert opinion on the significance of the new research. She told me 1cm over 20 years would be an “extremely high” amount. The glaciologist, who is also working on models for the Pine Island Glacier, stresses that all models include a degree of abstraction and uncertainty. However, her work also indicates that the glacier will make an increasing contribution to sea level rise in the coming years and describes the new study as a “considerable advance on the results of research to date.” Humbert says the results could well be applied to other glaciers of the same type.

Angelika Humbert from AWI took this picture flying over the Pine Island Glacier in a NASA DC8 as part of the IceBridge campaign in 2011

Durand’s new study shows that the glacier is now flowing at a rate and in a way that makes the process irreversible. Even if the air and ocean temperatures cooled off to what they were a hundred years ago – which is in no way likely – Durand is convinced the glacier would not recover. Durand says the study should arouse concern because the glacier has passed a “tipping point”, a much discussed concept in climate science. “That means because of our behaviour, our climate is changing and will continue to change a lot. I think it is one of the first times we are passing these tipping points.”

The scientist compares the situation to that of a cyclist coming down from the top of a mountain and unable to brake: “We have to fear that the retreat will continue, that other glaciers in the region will start to do the same, and that we will have a collapse of this part of the ice shelf. That would take centuries, but it would mean a rise of several metres in sea level.”

The last report by the Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change (IPCC) warned of the implications if the glaciers of West Antarctica were to become unstable. “Here,” says Durand, “we have proof that that is already happening with this one.”

At the Arctic Frontiers conference two years back, I heard a lot of interesting discussions about climate tipping points. Professor Carlos Duarte Directorof the Oceans Institute at The University of Western Australia and Research Professor with the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) talked to me at length about tipping points. Let me quote him briefly:

“Tipping Points – or thresholds – are levels of pressures beyond which small response of a property of interest becomes abrupt. Once a system or ecosystem or earth system crosses beyond a threshold, the changes, e.g. in the extent of ice or rate of warming, accelerate greatly, and once the threshold is crossed, it is sometimes very difficult to return to the original state even if pressure is released or reduced.”

We discussed the possible tipping points and warning signs outlined in a key piece of research by Timothy Lenton and others. Some would argue that tipping points have already been crossed in the Arctic region, which is known to be warming at least twice as fast as the rest of the earth. One of Lenton’s other key factors is the West Antarctic ice sheet becoming unstable. Now the “eternal ice” down south could be reaching a kind of “tipping point” in places. Yes, I know this only applies to a particular region of the West Antarctic, but the implications of irreversible glacier melt there are already huge. Greenland and that West Anarctic ice sheet play a key role in storing masses of fresh water, which would have huge implications if they melted. With marine glaciers, like the Pine Island Glaciers, the melt of white ice to expose more dark ocean surface underneath would further increase warming by absorbing solar heat instead of reflecting it back.

With the EU in the news today for considering moving away from binding climate targets, and little progress in sight towards an effective new climate agreement scheduled to be agreed in Paris in 2015, this all puts me in a pensive mood, as I get ready to head north and focus on the implications of the changing climate for “Humans in the Arctic”.

“On Thin Ice” at Warsaw climate talks

Did you know it was the “Day of the Cryosphere” at the Warsaw climate talks COP 19 in Warsaw yesterday? If not, you might be forgiven. I haven’t seen it making the headlines in the mainstream media. That is a pity, given that what climate change is doing to our ice, snow and permafrost has repercussions for the whole planet.

![]() read more

read more

“Penguins” ask Berlin to save Antarctic

Today, it seems, is World Penguin Day. If you happened to be in the German capital, Berlin, this would have been drawn to your attention by largish “penguins” visiting the embassies of Russia, China and Norway, as well as the German Agriculture Ministry, which, it may surprise you to know, is responsible for the protection of the Antarctic on behalf of the German government

Activists from “The Antarctic Ocean Alliance“, (AOA) made use of the occasion to draw attention to the need to protect the pristine ice region at the south of the world. The background is that Germany will be host to a meeting of the Commission for the Conservation of Antarctic Marine Living Resources (CCALMR) in July this year. The meeting, in Bremerhaven, home of Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for polar and marine research, will be discussing the possible creation of two Marine Protected areas (MPAs) in the Antarctic. The alliance, made up of WWF, Greenpeace, Deepwave, Whale and Dolphin Conservation (WDC) and others, is calling on Germany to play a leading role and on other key countries to support a decision in favour of the protected areas.

Steve Campbell, Campaign Director of the AOA, stressed Germany’s long tradition of scientific polar research and the key role the country could play in Antarctic protection. The alliance stresses that the Southern ocean is under increasing pressure from climate change and resource depletion. The areas the AOA want protected now are described by the campaigners as one of the world’s last wildernesses and an essential “living laboratory” for the planet.

Antarctic Peninsula is thawing faster

Ice in parts of the Antarctic Peninsula is now melting during the summer faster than at any time during the last thousand years, according to new research results. The scientists have reconstructed changes in the intensity of ice-melt, and the mean temperature on the northern Antarctic Peninsula since AD 1000, based on the analysis of ice cores.

According to the study, published in the journal Nature Geoscience, the coolest conditions and lowest melt occurred from about AD 1410 to 1460, when mean temperature was 1.6 °C lower than that of 1981–2000. Since the late 1400s, there has been a nearly tenfold increase in melt intensity from 0.5 to 4.9%. The warming has occurred in progressive phases since about AD 1460, but the melting has intensified, and has largely occurred since the mid-twentieth century. The study concludes that “ice on the Antarctic Peninsula is now particularly susceptible to rapid increases in melting and loss in response to relatively small increases in mean temperature”.

Paul Brown of Climate News Network says the findings explain a series of sudden collapses of ice shelves in the last 20 years, which scientists studying them had not expected. He also quotes the researchers as saying the current melting could lead to “further dramatic events, making the loss of large quantities of ice on the Peninsula more likely, and adding to sea level rise”.

The study is also of interest against the background of the debate going on over the last 20 years on whether the Antarctic would gain mass through extra snow falling and so REDUCE sea level rise, or would lose ice because of higher sea and air temperature and so exacerbate the effect.

The scientists use a 364-metre ice core from James Ross Island to get in insight into both past temperatures and ice melt. Layers in the core show periods when summer snow on the ice cap thawed and then refroze. By measuring the thickness of the layers, they could tell how the history of the melting related to changes in temperature at the site over the last thousand years.

Lead author Dr. Nerilie Abram of the Australian National University and the British Antarctic Survey (BAS) said: “Summer melting at the ice core site today is now at a level that is higher than at any other time over the last 1,000 years. And whilst temperatures at this site increased gradually in phases over many hundreds of years, most of the intensification of melting has happened since the mid-20th centrtury.

Dr. Robert Mulvaney from the BAS, who led the drilling expedition and co-authored the paper said: “Having a record of previous melt intensity for the Peninsula is particularly important because of the glacier retreat and ice shelf loss we are now seeing in the area. Summer ice melt is a key process that is thought to have weakened ice shelves along the Antarctic Pensinsula leading to a succession of dramatic collapses, as well as speeding up glacier ice loss across the region over the last 50 years”.

The changes on the Antarctic Peninsula do not necessarily apply to other parts of Antarctica, such as the West Antarctic ice Sheet. Melting is also occurring there and could have an even greater risk of large-scale sea level rise.

Paul Brown from Climate News Network notes “it is not clear that the levels of recent ice melt and glacier loss in West Antarctica are exceptional or are caused by human-driven climate changes.”

Lead author Abram says: “This new ice core record shows that even small changes in temperature can result in large increases in the amount of melting in places where summer tempearatures are near to 0°C, such as along the Antarctic Peninsula, and this has important implications for ice instability and sea level rise in a warming climate”.

I interviewed Andrew Shepherd, Professor of Earth Observation at the British University of leeds, on a major satellite sutdy of the polar ice melt towards the end of last year. It makes interesting listening to complement this latest development:

Interview with Andrew Shepherd

See also:

Polar ice sheets melting faster than ever

Are warming seas changing the Antarctic ice?

Photo gallery: High season for Antarctic researchers

China to step up polar activities in 2013

I am finding people increasingly interested in the Arctic and Antarctic as climate change opens up more prospects of getting at the natural resources in the region or using it for transport. The latest example of top-level international interest is an announcement by China. Beijing is planning to launch its 30th expedition to the Antarctic region this year as well as its 6th Arctic expedition. This interest is not new, but clearly intensifying. (See China’s Arctic ambitions spark concern).

According to China Daily, quoting a document released at a maritime work conference on Thursday, the country is also planning to build more Antarctic research bases. There are plans to put more resources into planes for scientific expeditions and to “ensure the quality of newly-built icebreakers”.

The paper also refers in particular to “the protection of the country’s strategic interests in the Arctic region”. Now there is some food for thought.

Increasing international political and strategic interest in the Arctic will be on the agenda at the Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromsö, Norway, starting January 21st. Watch this space.

Feedback