Search Results for Tag: CO2

Climate action from Peru to Paris

Today is the first of December. It’s the start of the meteorological winter in the northern hemisphere, towards the end of what looks set to be the warmest year since records began. It is also the day when the annual UN climate conference gets underway in Lima, Peru. Negotiators from around the world will try to hammer out the details of a new World Climate Agreement to halt global warming by reducing CO2 emissions. For our polar ice, that agreement can’t come fast enough.

After five years of frustration following the failure of the Copenhagen climate summit in 2009, 2014 may well go down in history as the year when climate change made a comeback onto the international agenda. Although there is still one year to go until the key Paris meeting which is scheduled to come up with a new World Climate Agreement to replace the Kyoto Protocol, 2014 has seen several milestones on the path to a low-carbon future.

In September, the UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon gave the issue top priority, by holding his own special climate summit in New York. It was accompanied by marches in the USA and other parts of the world, organized by a growing grassroots movement to combat climate change. Meanwhile, the world’s biggest emitters, China and the USA, finally signaled their intention to commit to action on climate change.

No time for delay

The latest report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the IPCC, has left no doubt about the need for urgent action, says Professor Stefan Rahmstorf from Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research:

“We see that global temperatures have risen by almost one degree centigrade in the last 100 years, we see that global sea level has risen by nearly 20 centimeters in the last 100 years. We see that the mountain glaciers and the Arctic ice cover is in retreat, the continental ice sheets in Greenland and Antarctica are shrinking, losing mass, contributing to sea level rise, we see extreme events on the rise. For example the number of record-breaking hot months has increased five fold as compared to what you get by chance in a stationary climate.”

The international community has agreed, based on the scientific evidence available, that a temperature rise of two degrees is the maximum possible without exposing the world to potentially devastating climate change. That means limiting the greenhouse gas emissions that are warming the planet. But with those emissions still on the rise, that goal is nowhere in sight, says Rahmstorf, and climate change is already having an impact after just under one degree of warming:

“If we don’t stop this process, we will go well beyond two degrees centigrade, and we will leave the range we are familiar with throughout human history. We will be way outside that into uncharted and I think very dangerous waters.”

Peru prepares the way for Paris

Experts see the world on track for a temperature rise of at least four degrees, unless emissions are reduced substantially in the very near future. The latest figures indicate that to stay within the two degree limit, emissions would have to peak within the next ten years and the world become virtually carbon-neutral in the second half of this century.

Peru’s Environment Minister and COP 20 President Manuel Pulgar-Vidal told me in Bonn this summer he was optimistic about the Lima meeting. (Pic: Quaile)

That is why Peru, like every climate conference, is important, says UN climate chief Christiana Figueres. She stresses that climate protection is an ongoing process. Countries have until March 2015 to put their planned contributions on the table. The EU made a start by announcing its targets last month. The USA and China went on to give encouraging signals:

“The fact is that most countries around the world are currently doing their homework and figuring out on a national scale what is financially, politically, economically, technically possible for them to contribute towards the solution,” says Figueres.

But while that homework continues in the countries of the world, the negotiators assembling in Lima will have to make progress on drafting the universal climate agreement, which is scheduled to be agreed in Paris in December 2015 and to come into effect in 2020.

A price on CO2

Ottmar Edenhofer is the chief economist at the Potsdam Climate Institute. He is also co-chair of the IPCC group concerned with ways of tackling climate change. He says the world has only around 20 to 30 years left to solve the emissions problem. He stresses it is not a question of technology. Alternative energy technologies are there to solve the problem. Yet fossil fuels have been enjoying a renaissance, says the climate expert. The key, he says, is to put a price on carbon, making it too expensive to pump CO2 into the atmosphere. The world only have a limited carbon budget. That means we can only put another one thousand gigatonnes of CO2 into the atmosphere to keep temperature rise below the two-degree threshold and avoid the risk of what Edenhofer describes as “very severe climate change impacts”.

“Space to store CO2 in the atmosphere is becoming scarce”, Edenhofer explained to me recently during a visit to Potsdam. “And when things are scarce, you have to put a price on them. That is the only way to show investors, consumers and companies where they should be investing their money.” The window of opportunity is closing, says Edenhofer. If we keep on with business as usual, we will have used up all our carbon budget in two to three decades.

UN climate chief Figueres agrees that putting a price on pollution by CO2 is a very important component of the shift towards a low carbon economy.

“What we have done over the past 150 years is assumed there is no cost to the irresponsible use of the environment, and we have proceeded as though the environment were constantly renewable, where it is not”, Figueres told me in an interview conducted in her office here in Bonn, right next to our Deutsche Welle building. Putting a price tag on CO2 emissions would mean they could be costed in economic decision-making.

Haggling out the details

The negotiators in Lima have their work cut out for them. Countries with large fossil fuel reserves are reluctant to agree to emissions reductions which would destroy their source of revenue. But Edenhofer is optimistic that ultimately all countries will realize that climate change will pay off in the end.

„We have to assume that people will see sense. They will realize that the long-term consequences of business as usual will be irreversible climate change, with all the problems that brings with it”.

The economist says protecting the climate would also bring the kind of short-term benefits politicians are looking for. He cites the change in China’s policies as an example:

“The drastic air pollution in Beijing is already making it less attractive as a business location. And the reason the Chinese government is thinking very seriously about reducing emissions is because it would also be a step towards improving their air quality.”

Funding boost for UN talks

After years of stagnation and frustration, there are signs that progress is being made on climate change. At a key meeting in Berlin this month, countries pledged a total of almost 10 billion dollars to the Green Climate Fund, which was set up to help poorer countries adapt to climate change. This could motivate developing countries and emerging economies to sign up to a new world climate agreement. So far, many of them have been reluctant to limit their own emissions, as the wealthy industrialized states are the ones who have caused the problem by emissions in the past.

Although both the money pledged for adaptation and the emissions cuts proposals currently on the table are still insufficient and things are moving slowly, German scientist Rahmstorf compares the likelihood of a breakthrough to the fall of the Berlin Wall, 25 years ago.

“If you had asked people just a few months before that how likely it was that the wall comes down, nobody would have said it’s going to happen”, says the Potsdam expert and IPCC author. He says these kind of processes in society are hard to predict – and the signs are encouraging.

He cites the “huge success story” of renewable energies and the considerable emissions reductions by the EU countries since 1990 as encouraging signs. This did not hamper economic growth, says Rahmstorf:

“It shows that your can decouple emissions from economic growth and welfare”.

Ultimately, halting climate change is not something which can be achieved solely within the UN negotiations. This year for the first time a pre-conference meeting was held in Peru to involve non-governmental groups in the process. The transition to a climate-saving low-carbon society requires action across the board. But it is the governments of the world who have to enter into binding agreements, and that means plenty of hard work ahead for the negotiators in Peru over the next two weeks.

Listen to my Peru conference preview on Living Planet.

Acid Arctic Ocean and Russell Brand?

Is ocean acidification a term you are familiar with? If you are a regular Ice Blog reader, I would like to think you will be. But I am prompted to ask this question because the term came up during a discussion at a weekly evening class I attend, and I was flabbergasted that none of the people there had a clue what it meant. These were all university-educated professionals. That means we in the media have our work cut out for us explaining how climate change is making the seas more acidic, and why this is something we should be worried about.

This incident has reminded me that we journalists have to avoid assuming that everyone is familiar with the terms we use in our coverage on a regular basis. Climate change is the kind of topic where you want to reach a specialist audience, but also the vast majority of the population. We all have to change our habits to reduce CO2 emissions, and we all have to vote for the politicians who have the responsibility for energy and environment policy. That means we need to talk about the problems in a way everybody understands.

I am encouraged to see the BBC website had a longer article on the threat of ocean acidification a few days ago. I don’t think it has made its way into the tabloids though, correct me if I am wrong.

I was made very aware of the issue during a trip to Arctic Spitzbergen in 2010 with a team of scientists monitoring just what happens to the life forms in the sea when it becomes more acidic because it is absorbing so much of the CO2 we emit. The polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster.

Greenpeace provided scientists with logistic support for the ocean acidification experiments off the coast at Ny Alesund, Spitzbergen. (Pic: Irene Quaile)

Towards the end of last year, I interviewed Professor Alex Rogers from the University of Oxford, who is also the scientific director of the International Programme on the State of the Oceans, which had just published a major study on acidification.

Listen to the interview:

He told me: “The oceans are taking up about a third of the carbon dioxide we’re producing at the moment. While this is slowing the rate of earth temperature rise, it is also changing the chemistry of the ocean in a very profound way.”

Carbon dioxide reacts with sea water to form carbonic acid. Gradually, this makes oceans more acidic.

Threat to marine life

Sea water is already 26 percent more acidic than it was before the onset of the Industrial Revolution. According to the IPSO report, it could be 170 percent more acidic by 2100.

Over the last 20 years, scientists around the world have been conducting laboratory experiments to find out what that would mean for the flora and fauna of the oceans. Ulf Riebesell of the Helmholtz Institute for Ocean Research in Kiel, a lead author of the report, conducted the world’s first experiments in nature, off the coast of the Arctic island of Svalbard in 2010. This was the project I visited.

Giant test-tubes were lowered into the ocean to capture a water column with living organisms inside it. Different amounts of CO2 were added to simulate the effects of different emissions scenarios in the coming decades. The experiments showed that increasing acidification decreases the amount of calcium carbonate in the sea water, making life very difficult for sea creatures that use it to form their skeletons or shells. This will affect coral, mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish as well as fish and other organisms. Scientists say some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future.

Hard times for coastal residents

All this will have severe economic and social consequences. Ultimately, acidification will affect the food chain. Tropical and sub-tropical areas with warm-water corals are going to suffer. Coral reefs are home to numerous species, serve as nurseries for fish and are a valuable tourist attraction. They also protect coastlines against waves and storms.

At the same time, the polar regions are suffering more than others, as cold water absorbs CO2 faster. Riebesell told me the experiments in the Arctic indicate that the sea water there could become corrosive within a few decades. “That means the shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve.” What a horrific prospect.

The Antarctic is already affected. IPSO’s Alex Rogers told me: “We’re seeing instances where we’re finding tiny shelled molluscs, tiny snails that swim in the surface of the oceans, with corroded shells.”

These creatures play a key role in the marine food chain, supporting everything from tiny fish to whales. “One of our primary sources of marine-derived protein is in rapid decline,” says Monty Halls, manager of the UK-based Shark and Coral Conservation Trust. He describes ocean acidification as the “most serious threat to our children’s welfare.” Monty is working to produce video and cartoon material to interest the younger generation in the need to change our behavior to protect marine life.

Two German scientists Antje Funcke and Konstantin Mewes have written and illustrated a children’s story called Tipo and Tessi to make kids aware of the need to protect the ocean. So far, it has only been published in German. The English translation is available, but so far there is a lack of funding for publication.

Vicious circle of climate change

Scientists are also concerned about a feedback effect that will further exacerbate global warming. In the long run, the ocean will become the biggest sink for human-produced CO2, but it will absorb it at a slower rate. That means the more acidic the ocean becomes, the less capacity is has to act as a buffer.

Alex Rogers sees a further problem: “Carbonate structures actually weigh down particular organic carbon. In other words, they help carbon to sink out of the surface layers of the ocean into the deep sea. Anything that interferes in that process can potentially accelerate the rate of CO2 increase in the atmosphere.”

And that would be very dangerous. “The rates of CO2 increase we are seeing at the moment are probably as high as they’ve been for the last 300 million years,” says Rogers.

The IPSO scientists draw an unsettling comparison between conditions today and climate change events in the past that have resulted in mass extinctions. They say a lot of these major extinction events occurred in connection with high temperatures and acidification, similar effects to the ones that we are experiencing today.

The BBC article I mentioned earlier also mentions new research by scientists at Exeter University, indicating that increasing acidity creates conditions for animals to take up more coastal pollution, like copper. That would mean not only creatures with calcium-based shells would be endangered.

Find a celebrity champion?

The experts stress that it is not too late to halt the acidification process, although the CO2 will remain in the oceans for thousands of years. This brings me back to the topics of recent Ice Blog posts: the UN climate negotiations and the need for urgent action. And of course, to the mention in the title above of the British comedian Russell Brand. This relates to another issue I have been writing about recently: the question of celebrity involvement and whether that can help inform people about and interest them in topics like climate change and the acidification of our oceans. My commentary on this, with regard to Leonardo di Caprio at Ban Ki-moon’s September summit in New York, sparked some interesting discussions.

Just this morning I was reading about Russell Brand and how his new book calling for a revolution on all kinds of issues is attracting huge interest. I have noticed that people otherwise completely uninterested in politics and social issues are at least paying some attention because their favourite comedian is talking about them. Maybe we have to get Russell Brand on board. I’m not sure what kind of action he would advocate, but there would certainly be a lot fewer people who could say they’d never heard of ocean acidification.

Can UN and EU take the heat off Alaska?

It is with a heavy heart that I write this first blog post since my holiday, catching up with the latest climate news. A piece by Alex Kirby of Climate News Network drews my attention to the fact that temperatures in Barrow, Alaska, one of the first places to feature on the Ice Blog when it was created in 2008, have risen by an astonishing 7°C in the last 34 years (looking at the average October temperature). As Alex Kirby puts it, “an increase that, on its own, makes a mockery of international efforts to prevent global temperatures from rising more than 2°C above their pre-industrial level”. We need more climate action

![]() read more

read more

The Arctic on the UN agenda

US icon sinking in melting ice? The photo was taken in the Arctic Ocean northwest of Svalbard the 7th of September 2014.

(Christian Auslund / Greenpeace)

To those of us who deal with the Arctic on a regular basis, the significance of the melting ice for the UN climate negotiations and vice versa is abundantly clear. But not everybody understands all the connections. A major media event like this week’s New York climate summit hosted by the UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon in person was a fine chance to focus attention on the need to protect the Arctic. Greenpeace made good use of it, handing over a petition with six million signatures just ahead of the big event, and with hundreds of thousands gathered in New York for the Climate March.

It was timely in more ways than one, just as the latest sea ice figures were published to confirm the melting trend.

The petition calls for long-term protection of the Arctic, with the region warming more than twice as fast as the global average and opening the high north to shipping and commercial exploitation. Greenpeace and other groups are calling for a ban on oil exploration, which could endanger the fragile ecosystem. Experts also have safety concerns about increased shipping.

Ban Ki-moon receives the Greenpeace delegation with the petition. The delegation consists of Indigenous rights activist, youth leader and Saami politician Josefina Skerk, Margareta Malmgren-Koller, Greenpeace Senior Political Advisor Neil Hamilton and Greenpeace International Executive Director Kumi Naidoo. Photo: Michael Nagle / Greenpeace

Commercial development versus environment

Earlier this month, a survey showed that 74% of people in 30 countries support the creation of a protected Arctic Sanctuary in the international waters surrounding the North Pole. The study was commissioned by Greenpeace and carried out by Canadian company, RIWI. Around the same time, the Arctic Council, which combines the Arctic states and indigenous peoples’ representatives, currently chaired by Canada, supported the founding of a new business grouping, the Arctic Economic Council. Its aim is to promote the commercial development of the Arctic region. I wrote about this here on the Ice Blog and on the DW website.

Global responsibility for the Arctic

The UN Secretary General accepted the Greenpeace petition saying:

“I receive this as a common commitment toward our common future, protecting our environment, not only in the Arctic, but all over the world.”

Ban Ki-moon said he would consider convening an international summit to discuss the issue of Arctic protection. He also expressed a desire to travel aboard one of the organisation’s campaigning ships in the Arctic in the near future.

Greenpeace Executive Director Kumi Naidoo, who was part of the delegation, said: “The Arctic represents a defining test for those attending the summit in New York”.

He said leaders should bear in mind that concern for the rapid warming of the world was not consistent with planning oil and gas development in the melting Arctic.

The small delegation that met Ban Ki Moon included Indigenous rights activist and Saami politician Josefina Skerk, who last year trekked to the North Pole to declare the top of the world ‘the common heritage of everyone on earth’.

Skerk, a member of the Saami Parliament, said: “We, who want to continue living in the North, are gravely concerned about climate change and the destructive industries that are closing in. My people know and understand the Arctic, and it is changing in a manner, which threatens not just our survival, but the survival of people all over the world.”

Skerk said humans had created the crisis and had to take action to solve it.

“I urge the Arctic countries in particular to take a giant step up and I think the world needs to pay much closer attention to ensure that it happens. They might as well start here in New York.”

From Kiribati to Svalbard and New York

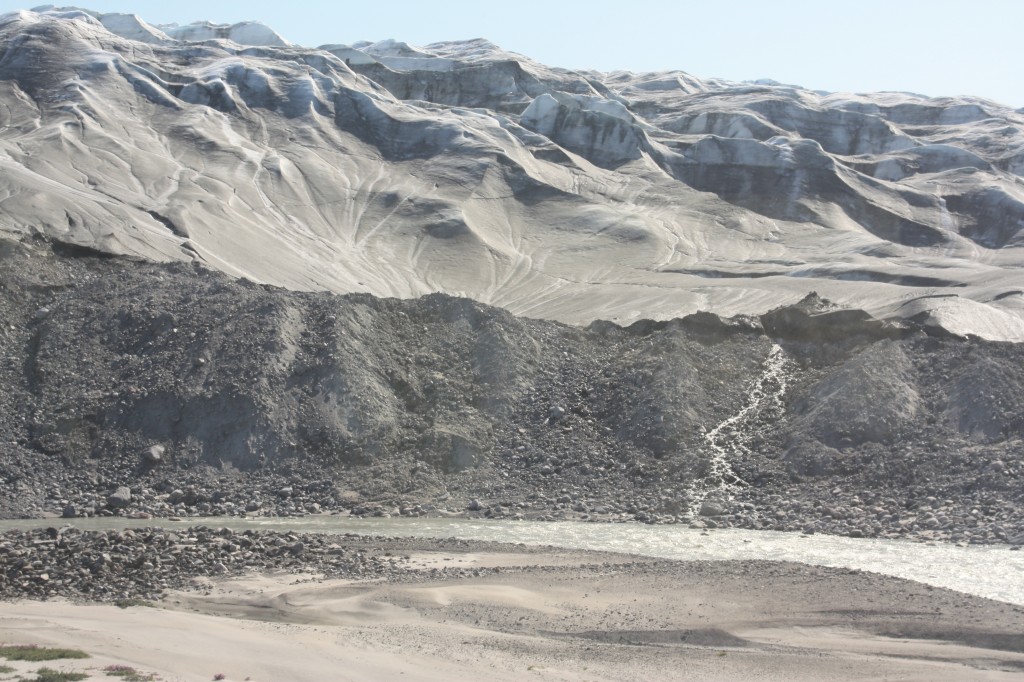

Melting ice especially from the Arctic Greenland ice sheet is raising sea levels around the globe, endangering low-lying areas. At the weekend, the President of Kiribati, Anote Tong, ended a Greenpeace-organized tour of glaciers in Norway’s Svalbard Archipelago. He said the trip to the Arctic ice had made a deep impression on him, which he would share with world leaders at the U.N. climate summit:

“It’s a very fascinating sight. In spite of that, what I feel very deeply is the sense of threat,” Tong said. “If all of that ice would disappear, it would end up eroding our shores.”

Kiribati is a group of 33 coral atolls located about halfway between Hawaii and Australia. Many of its atolls rise just a few feet above sea level.

In last year’s report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), experts concluded oceans could rise by as much as 1 meter (3.3 feet) by the end of this century if no action is taken to cut the greenhouse gas emissions causing global warming.

“It won’t take a lot of sea level rise to affect our islands,” Tong said. “We are already having problems.”

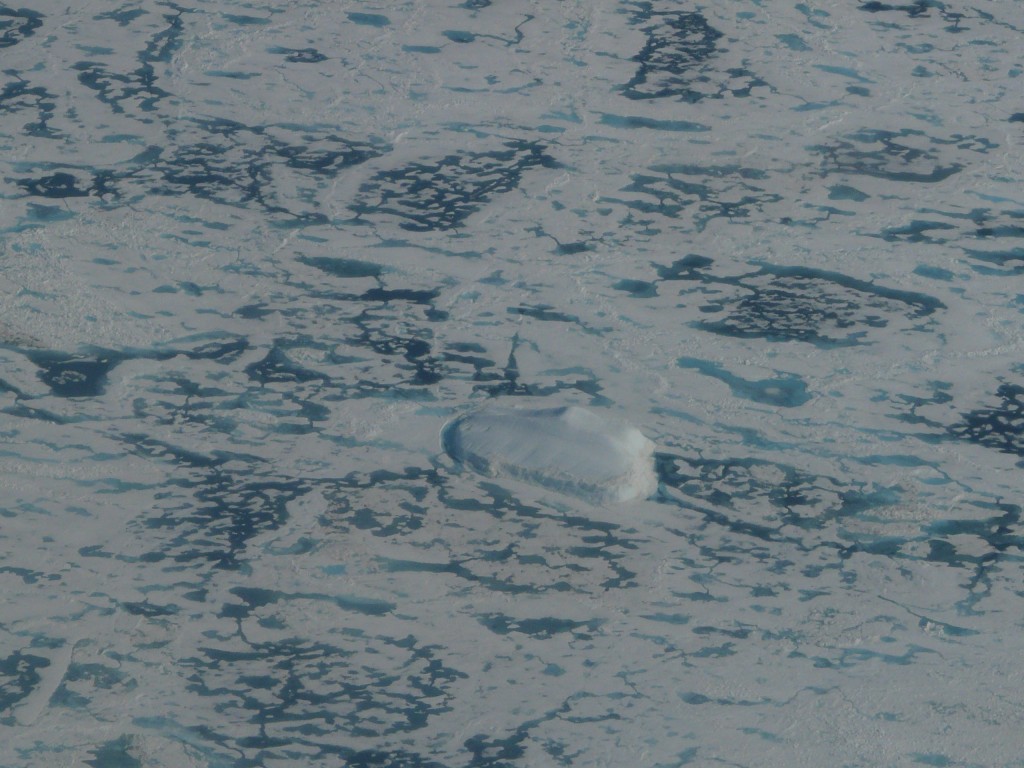

Sea ice minimum confirms melting trend

The New York summit coincides with the annual announcement of the minimum sea ice for the year, as the summer season comes to an end. The sea ice – in contrast to glaciers on land – does not influence global sea level, but is regarded as a key indicator of how climate change is affecting the region. This year the figure announced by the US National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC) was 5.01 million square kilometers. The figure is the sixth lowest extent since records began.

The minimum ever recorded at the North Pole was 3.29m sq km in 2012 – and the eight lowest years have been the last eight years.

Ice levels in the Arctic have recovered from their all-time low, but are still on a shrinking trend, said Julienne Stroeve of the National Snow and Ice Data Centre. ”We have been telling this story for a long time, and we are still telling it,” she said.

NSIDC records showed that, this year, ice momentarily dipped below 5million sq km to 4.98m on 16 September, but the official figure is taken from a five day average.

Satellite data shows that one part of the Laptev Sea was completely clear from sea ice for the first time this summer. One of the most important questions for climate scientists is how soon the Arctic will experience its first sea ice-free summer.

Rod Downie, head of WWF UK’s polar programme, said that this year’s new Arctic minimum should prompt new action from the leaders meeting in New York. He stressed the connection between the Arctic and weather conditions in other parts of the world:

“As David Cameron prepares to meet other global leaders at the UN climate change summit in New York, the increased frequency of extreme weather that is predicted for the UK as a result of a warming Arctic should serve as a reminder that we need urgent action now to tackle climate change,” he said.

The summit was a major PR event to draw attention to the need for urgent and substantial climate action. The accompanying protests around the globe show people are not happy with the slow pace of the climate talks and their governments’ efforts to reduce emissions. Of course there was little in the way of concrete pledges. Still, on the whole, I see it as a successful step on the way to a new climate agreement because it has put the spotlight on climate change at a time where international conflicts are dominating the news agenda.

More commentary on the summit from me here:

World leaders must act as climate takes centre stage

All-star gala puts climate back on the agenda

Coal, climate, cryosphere

The Greenland ice sheet is melting faster. Scientists also report a decreasing albedo with snow becoming darker. (Pic: I.Quaile)

Fossil fuel power plants are still on the increase – committed carbon emissions are rising fast. At first glance you might respond to that with “so what’s new”? Well, a study is new, which indicates that in spite of all the political rhetoric in a lot of places about switching to renewable energies and moving away from fossil fuels, we are building more fossil fuel power plants than ever before. Unsurprisingly, that is leading to an increase of carbon dioxide emissions, which is bad news for plans to keep global temperature rise below 2°Celsius. It is extremely bad news for those of concerned about the cryosphere and the increasing melt rates of Greenland and parts of Antarctica. The main problem, the authors tell us, is that we have already committed to huge emissions by investing in polluting technologies.

Steven Davis of the University of California, Irvine and Robert Socolow of Princeton University in the US, report in the journal Environmental Research Letters that existing power plants will emit 300 billion tons of additional carbon dioxide into the atmosphere during their lifetimes. In this century alone, emissions from these plants have grown by 4% per year.

The two scientists have already reported on the increasing costs of delay in phasing out fossil fuel sources of energy, notes Tim Radford of the Climate News Network. Thanks again to you people for drawing attention to the study. Their latest research looks at the steady future accumulation of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere from power stations.

“Despite international efforts to reduce CO2 emissions, total remaining commitments in the global power sector have not declined in a single year since 1950 and are in fact growing rapidly,” the report states.

Massive emissions already committed

Governments worldwide have in principle accepted that greenhouse gas emissions should be reduced and average global warming limited to a rise of 2°C.

At the current pace though, scientists have warned that the world is on track for at least 4° Celsius by the end of the century. That could mean drastic rises in sea levels and catastrophic drought in some areas of the world.

“We are flying a plane that is missing a crucial dial on the instrument panel,” said Socolow. The needed dial would report committed emissions. Right now, as far as emissions are concerned, the only dial on our panel tells us about current emissions, not the emissions that capital investment will bring about in future years.”

In the latest study, scientists asked: once a power station is built, how much carbon dioxide will it emit, and for how long? They assumed a functioning lifetime of 40 years for a fossil fuel plant and then tallied the results.

The fossil fuel-burning stations built worldwide in 2012 alone will produce 19 billion tons of carbon dioxide over their lifetimes. The entire world production of the greenhouse gas from all of the world’s working fossil fuel power stations in 2012 was 14 billion tons.

“Far from solving the problem of climate change, we’re investing heavily in technologies that make the problem worse,” the experts stress.

The US and Europe between them account for 20% of committed emissions, but these commitments have been declining in recent years. Facilities in China and India account for 42% and 8% respectively of all committed future emissions, and these are rapidly growing in number. Two-thirds of emissions are from coal-burning stations ad the share from gas-fired stations had risen to 27% by 2012.

Fossil fuel wind-down not fast enough

Davis says more fossil fuel-burning facilities have to be retired than new ones built. “But worldwide we’ve built more coal-burning power plants in the past decade than in any previous decade, and closures of old plants aren’t keeping pace with this expansion”, he added.

According to Socolow, a high-carbon future is being locked in by the world’s capital investments: “current conventions for reporting data and presenting scenarios for future action need to give greater prominence to these investments,” he said.

The current draft of a summary report to the International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) due to be released in November and viewed by the Times this week, warns of “severe, pervasive and irreversible impacts” unless carbon emissions are brought under control. The IPCC stresses that human-induced climate change will lead to the devastation of homes and property, a scarcity of food and water and human mass migration, as sea levels rise through warming temperatures and – alas – melting ice.

Feedback