Search Results for Tag: Paris Agreement

Trump’s alternative reality? No warming, cool oceans, intact coral

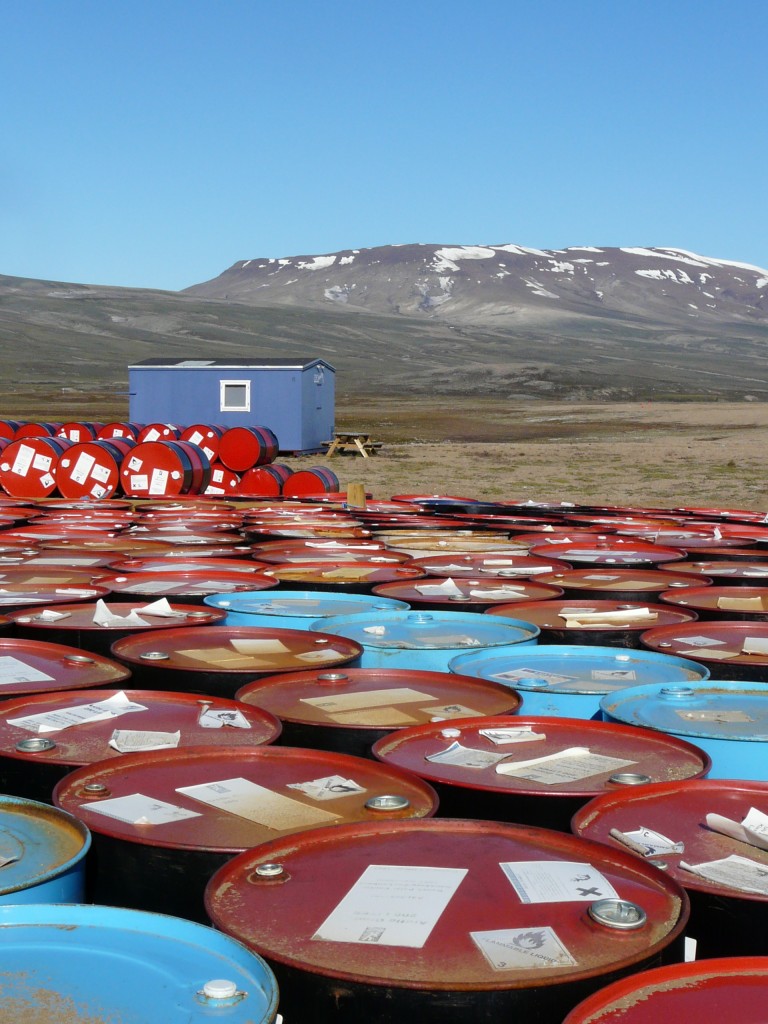

Melting or not? (I.Quaile, Greenland)

“Irene, have you heard the news? Looks like Trump has pulled out of the Paris Agreement.” While the US President kept the suspense up until Thursday night – has he, hasn’t he, will he, won’t he -I struggled to reconcile his action with what I was hearing from a wide spectrum of highly intelligent people with decades of research and experience to their credit.

I was in Kiel this week, on Germany’s Baltic coast, attending a working meeting of the scientists involved in BIOACID, a national German programme (supported by the BMBF, Federal Ministry of Education and Research) to investigate the “Biological Impacts of Ocean Acidification”. It has almost run its course, eight years of research in the bag.

And what I was hearing did nothing to allay my concern about the impacts of our greenhouse gas emissions. We are rapidly and undeniably changing the planet we live on – land and sea. And that applies particularly to the Arctic.

GEOMAR’s research vessel Alkor in Kiel getting ready for her next trip (Pic:.I.Quaile)

The scientific evidence

Can President Trump really fail to see the dangers of our human interference? Is he really oblivious to what climate change is doing to the ocean that covers 70 percent of the surface of our planet?

Maybe he lives in a parallel universe, where alternative facts prevail.

Back in 2010, I was able to witness the work of some of the scientists assembled in Kiel this week at first hand, as they lowered mesocosms, a kind of giant test tubes, into the Arctic Ocean off the coast of Svalbard. The aim was to find out how the life forms in the water would react to increasing acidification of their environment, as our greenhouse gas emissions result in more and more CO2 being absorbed into the ocean.

Drawing the threads together

Ulf Riebesell with team members deploying experiments at Svalbard (Pic.I.Quaile)

Ulf Riebesell is Professor of Professor of Biological Oceanography at, GEOMAR, the Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research in Kiel, and the coordinator of BIOACID.

When I first met him, he was kitted out in survival gear, supervising the transport and deployment of the mesocosms from Germany up to the Svalbard archipelago. He doesn’t need the cold-weather gear this week, in a summery Kiel, where he gathered representatives of the different working groups involved in the German project to draw some threads together as the project approaches its conclusion in November.

Good timing. The results will be ready to hand to the delegates attending this year’s UN climate extravaganza, COP23, in Bonn. Another key piece in the jigsaw puzzle of how climate change is affecting the world we live in and will determine the future of coming generations.

All creatures great and small

The scientists assembled represent a wide range of expertise. From the tiniest of microbes through algae, corals, fish and the myriad organisms that live in our seas- they have been trying to find out what happens when living conditions change for our fellow planetary residents – and how all this affects an ever-increasing population of humans and the complex societies we live in.

The ocean is changing at an unprecedented rate. It is becoming warmer, even in the depths, and it is becoming more acidic.

The work of Riebesell and his colleagues has shown that in our rapidly warming world, the CO2 that goes into the ocean is reducing the amount of calcium carbonate in the sea water, making life very difficult for sea creatures that use it to form their skeletons or shells. This will affect coral, mussels, snails, sea urchins, starfish as well as fish and other organisms. Some of these species will simply not be able to compete with others in the ocean of the future.

Cold water coral in the GEOMAR lab in Kiel. (Pic.I.Quaile, thanks to Janina Büscher)

The Arctic predicament

Acidification is not something that affects all regions and species equally. Once again, the Arctic is getting the worst of it. Cold water absorbs CO2 faster. Experiments in the Arctic indicate that the sea water there could become corrosive within a few decades, as Ulf Riebesell has told me on several occasions since I first met him on Svalbard in 2010. “That means the shells and skeletons of some sea creatures would simply dissolve.”

Scientists warn that a combination of acidification, warming and stressors like pollution of all sorts will ultimately affect the food chain. (Indeed that is already happening).

Warming as usual?

While the BIOACID project comes to an end and the scientists fight for new funding to carry on research into ocean acidification, which requires a combination of field-work and modelling, the world continues on course for far more than the two degrees – or 1,5 set out in the Paris Agreement.

“Ocean Warning” was the cover title on the Economist magazine this week, ahead of next week’s UN Oceans Conference in New York.

“The Paris Agreement is the single best hope for protecting the ocean and its resources”, the magazine reads. But it stresses: “the limits agreed on in Paris will not prevent sea levels from rising and corals from bleaching. Indeed, unless they are drastically strengthened, both problems risk getting much worse. Mankind is increasingly able to see the damage it is doing to the ocean. Whether it can stop it is another question”.

Seaweed and algae in experimental tanks at GEOMAR, Kiel (Pic.I.Quaile)

Bending the truth?

At the meeting in Kiel, I asked Professor Hans-Otto Pörtner, the other coordinator of BIOACID, senior scientist at the Alfred Wegener Institute and co-chair of the IPCC Working Group 2 for his view of the current situation, with US President Trump getting set to leave the Paris Agreement:

“Climate change is clearly human made, responsible leadership means that this cannot simply be denied or ignored. I think this is a call for better education and information of the public so that it cannot be misled by bending the truth – and this is what it comes down to. As the last report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) put it: “Without additional mitigation efforts beyond those in place today, and even with adaptation, warming by the end of the 21st century will lead to very high risk of severe, widespread and irreversible impacts”. In its previous analysis of decision-making to limit climate change and its effects, the IPCC also noted that climate change is a problem of the commons, requiring collective action at the global scale. Effective mitigation will not be achieved if individual agents advance their own interests independently.”

Call to action

Indeed. We are all in this together.

But there is not only bad news:

“It remains to be seen to what extent U.S. emissions will be driven by federal policy, or actions at the State and city level, or by market and technological changes”, Professor Pörtner told me.

There is, it seems to me, an upside to President Trump’s decision to live in his own alternative reality. It galvanizes those of us who live in the real world to make sure climate action goes ahead. China and the EU closed ranks this week. States, companies, civil societies and committed individuals across the USA are stressing they will press on with the green energy revolution regardless.

In the interests of the icy north – and the rest of the planet it influences so considerably – we really have no choice.

The mesocosms are used to research the effects of acidification on ocean-dwellers. (I.Quaile, Svalbard)

LISTEN:

Living Planet: STAND UP FOR THE PLANET

Living Planet: UN TALKS IN TRUMP’S SHADOW

READ:

LEAVING PARIS AGREEMENT A BREACH OF HUMAN RIGHTS?

Arctic summer sea ice cover could disappear with 2C temperature rise

The sea ice has been dwindling for decades (Photo: I Quaile)

The Arctic sea ice may disappear completely in summers this century, even if the world keeps to the Paris Agreement. That is the worrying message of a report published on Monday in the journal Nature Climate Change.

The 2015 Paris Agreement set a goal of limiting the rise in global temperature to well below two degrees Celsius (3.6 Fahrenheit) above pre-industrial times. Ideally, 1.5C (2.7F) was agreed to be the “aspirational” target. James Screen and Daniel Williamson of Exeter University in the UK, wrote, after a statistical review of ice projections, that a two degree Celsius rise would still mean a 39 percent risk that ice would disappear from the Arctic Ocean in summers. If warming is kept to 1.5 degrees Celsius, the ice was virtually certain to survive, they calculated.

Current emissions targets way too low

Looking to an uncertain future. Svalbard polar bear. (Pic. I.Quaile)

If you take the old “glass being half-full rather than half-empty” metaphor, you could see that as a positive option to hang on to. However, the scientists estimated that if we continue along current trends, temperatures will rise by three degrees C (5.4 F.). That would give a 73 percent probability that the ice would disappear in summer. To prevent it, governments would have to up their targets and make considerably larger cuts in emissions than presently planned.

The sea ice will reach its maximum winter extent some time soon. So far, the March figures rival 2016 and 2015 as the smallest for the time of year since satellite records began in the late 1970s.

“In less than 40 years, we have almost halved the summer sea ice cover”, Tor Eldevik, a professor at the Bjerknes Centre for Climate Research at the University of Bergen in Norway, told Reuters. Eldevik was not involved in the study.

He predicted that sea ice would vanish in the Arctic Ocean in about another 40 years, on current trends.

… And the ice just keeps on melting. (Pic: I. Quaile,) Greenland)

Steady melting trend

Scientists define an ice-free Arctic Ocean as one with less than one million square kilometers (386,000 square miles) of ice, because they say some sea ice will linger in bays, for instance off northern Greenland, even after the ocean is ice-free.

Despite fluctuations from year to year, long-term trends in the Arctic clearly show a decline in sea ice. The ten lowest ice extents since 1979 have all occurred since 2007.

According to the latest figures from the NSIDC (March 6), high air temperatures observed over the Barents and Kara Seas for much of this past winter moderated in February. Still, overall, the Arctic remained warmer than average and sea ice extent remained at record low levels.

Arctic sea ice extent for February 2017 averaged 14.28 million square kilometers (5.51 million square miles), the lowest February extent in the 38-year satellite record. This is 40,000 square kilometers (15,400 square miles) below February 2016, the previous lowest extent for the month, and 1.18 million square kilometers (455,600 square miles) below the February 1981 to 2010 long term average.

Good times ahead for Arctic shipping, trade and tourism? Not much of a future for polar bears struggling for survival, or for people whose livelihood and way of life depends on reliable ice cover.

Will new climate scientist on board influence Exxon?

Last year I had an interesting guest in the studio here at Deutsche Welle. We talked for a good half hour about climate change and the ocean and the need for the Paris Agreement to be put into action, and whether we can still save the Arctic ice as we have known it in our lifetimes.

Excerpts from the interview were broadcast on Living Planet and published online.

Susan Avery is an atmospheric scientist. She was President and Director of the renowned Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute from 2008 to 2015, and became a member of the scientific advisory board to UN Secretary General Ban Ki Moon in 2013. She was in Bonn for a lecture organized by Björn Müller-Bohlen from the department of strategic partnerships at the Forum of International Academic Sciences in Bonn, to explain to people here how climate change is affecting the ocean.

I was surprised to say the least when I saw that from the beginning of February Dr. Susan K. Avery had been elected to the board of directors of ExxonMobil.

Topsy-turvy world?

So the former Exxon chief Rex Tillerson has taken the key post of Secretary of State in the Trump administration, climate skeptic Scott Pruitt takes over the EPA, the world worries about the future of the climate and the environment – and a leading climate scientist has joined the “largest publicly traded international oil and gas company and one of the largest refiners and marketers of petroleum products”, as ExxonMobil describes itself. It is also at the centre of a huge controversy over claims that it denied climate change, covering up facts and funding climate skeptic bodies. Interesting times indeed. (The Dawn of the Trumpocene?) What are we to make of it all?

I emailed Dr. Avery to try to arrange another interview to discuss her motivation and expectations. She did respond swiftly, telling me she was “honored to be elected to the Board and look forward to serving in that capacity.” But interview requests are being handled by Exxon.

Reactions to her appointment have been mixed, ranging from those who see this as a mere greenwashing type of move by Exxon, and those who think this represents a gradual shift in thinking in the corporation (pragmatic shift to renewable energies given the problems ahead for fossil fuel companies?) and the optimists who think this could possibly even be a chance for a climate expert to influence the policies of the fossil fuel giant and a sign that the times are ‘a changin’.

From the “horse’s”mouth

I decided to have another look and listen to the interview I recorded with Dr. Avery last year, to remind myself and those who will be watching her actions with interest, of what she stands for when it comes to protecting the climate, the ocean and the Arctic.

She is certainly in no doubt about the human factor in climate change. When I mentioned that we humans had been “interfering” with the climate, she laughed good-naturedly at my under-statement, and went on to elaborate on how we are increasing the temperature of the atmosphere by infusing carbon into it. She clearly named fossil fuels as a cause. So what, I wonder, will she be telling the board of ExxonMobil?

Our subject was the effect of greenhouse gas emissions on the oceans in particular. She stressed that while 25 percent of the carbon dioxide we release goes into the atmosphere, a stunning 93 percent of the extra warming created is in the ocean. I went on to ask her about the impacts:

“The carbon dioxide we’ve put into the atmosphere already and the heating associated with that means that we’re already pre-destined for a certain amount of global temperature increase. Many people say we have already pre-destined at least one and a half degrees, some will say almost two degrees. That’s why it’s really important to address the warming questions. And I was really pleased to see the Paris Agreement finally signed off on.”

Fossil fuel threat to the ocean

With the future of US participation in implementing the Paris Agreement very much up in the air under the Trump administration, one wonders how Avery is going to push the decarbonisation of the economy necessary to keep anywhere near the two degree limit, on the board of one of the world’s biggest oil and petroleum concerns.

She also stressed in her talk with me the huge threat to the food chain posed by ocean acidification, as carbon dioxide emissions change the PH of the ocean.

“Our coral reef systems and a lot of our ecosystems in the ocean are having a battle with warming, and those ecosystems that involve shell production and reproduction, as in our reef systems, are also battling acidification issues. This is really critical, because it attacks a lot of the base of the food chain for a lot of these eco-systems. “

Another of the threats to the ocean and the creatures in it is pollution, and Avery told me her time as head of Woodshole was a time of “many crises in the ocean” – including the Deep Water Horizon oil spill:

“That was a real challenge for us in terms of looking at the technologies we have in a different way, solving a different type of problem, and from these crisis moments we learned a lot about our science and our technology, and how to improve it and go forward.”

Well, here’s hoping that knowledge and Dr. Avery’s expertise here will help the company where she is now on the board.

Scientists are concerned about the effects of ocean acidification. This mesocosm is monitoring in Arctic waters. (I.Quaile)

Kudos for the journos

Another point that came out of our interview was Avery’s firm belief in the key role the media have to play in explaining what is happening to our climate and environment to “ordinary people”.

“It is things like Living Planet and others that really begin to educate people and involve people in understanding their environment and their planet,” she said in the DW studio.

As host and producer of Living Planet together with my colleague Charlotta Lomas, it was good to have that acknowledgement from a leading scientist and adviser to the UN. Avery also mentioned progress in recent decades in raising public awareness of environmental issues, such as pollution or acid rain, thanks not least to media coverage.

Unfortunately that job is not made any easier – especially in the United States – with an administration that tries to gag journalists and, it seems, any organization that does not spread the information the government think should be spread.

Motives and methods

So what motivates someone like Susan Avery to take on a controversial position like board membership on a company whose main business results in harmful changes to the planet which she has been working for years to publicise? Perhaps another snippet from the interview can shed some light, when I asked my guest Avery how she had come to be a member of the board of advisors to Ban Ki Moon (not that I would compare that to joining ExxonMobil).

“I was intrigued by the opportunity to play on a stage level that was very high politically, and making sure that science was interfaced in a number of dimensions, into the policy and decision-making process at that level. The committee itself is a wonderful board in terms of the different disciplines represented, different countries represented, different perspectives we all have on the science and the environment, and on human health issues, that the UN needs to be cognizant of.”

Clearly, this is a woman who likes to be in influential positions – and to bring different camps and expertise together:

“We talked a lot about science, the policy-society interface, the role and engagement of stakeholders, those are governments at all levels, the business community, and conservation.

What about the Arctic?

Of course one of the Iceblogger’s most urgent concerns is what climate change is doing to the polar regions. With record temperatures in the Arctic and record low sea ice cover, I asked Avery to sum up the impacts for our Living Planet listeners. She expressed her concern that “we are beginning to see a very rapid increase in ice loss in the Arctic”. She cited the melting of the big land ice glaciers as a major contributor to sea level rise. She talked of how not only atmospheric temperature but warming ocean waters are degrounding glaciers and melting ice from below:

“That is a major concern for sea level rise, but also because when the land-based ice comes into the ocean, you get a freshening of certain parts of the ocean, so particularly the sub-polar north Atlantic, so you have a potential for interfacing with our normal thermohaline circulation systems and (this) could dramatically change that. Changes in salinity are beginning to be noticed. And changes in salinity are a signal that the water cycle is becoming more vigorous. So all of this is coupled together. What’s in the Arctic is not staying in the Arctic. What’s in the Antarctic is not staying in the Antarctic. I would say the polar regions are regions where we don’t have a lot of time before we see major, massive changes”.

So let us hope Dr. Avery will be able to convince her fellow board-members and the decision makers at ExxonMobil about that – and about what has to happen. Fossil fuel emissions in general have got to go down. And the fragile Arctic in particular is in need of protection. Clearly, she has her work cut out for her.

Is there still time?

Reporting Avery’s appointment to the ExxonMobil board, the news agency AFP quotes her as saying:

“Clearly climate science is telling us (to) get off fossil fuels as much as possible.”

I asked her whether she believed, given that we have already put so much extra CO2 into the atmosphere and the ocean, that there was any way we would be able to reverse what is happening in the Arctic. Her reply – unsurprisingly – was not too reassuring:

“I don’t have an answer, to be honest. I think we’re still learning a lot about the Arctic and its interface with lower latitudes, how that water basically changes circulation systems, and on what scale. (…)We know so little, about the Arctic, the life forms underneath the ice (…) And I think it’s really important, because the Arctic will be a major economic zone. We’ve already seen the North-West Passage through the Arctic waters, we’re going to see migration of certain fisheries around the world, and we don’t even know completely what kind of biological life we have below that ice. We have the ability to get underneath the ice now. I call these the frontiers, of the ocean, and that includes looking under ice. It’s a really exciting time.”

If that excitement can be put into protecting the fragile polar ecosystems rather than taking advantage of our emissions misdeeds to date to use easier access for commercial exploitation, I am all for it.

ExxonMobil remains a primary target of environmentalists. It has been the subject of investigative reports by environmental news nonprofit Inside Climate News and others, saying it “manufactured doubt” about climate science even while contradicted by research by its own climate scientists. The company says the reports are biased, but faces government investigations over the controversy. In January, a Massachusetts court ruled the oil giant must turn over 40 years of documents on climate change, in a win for Massachusetts Attorney General Maura Healey, who has described the probe as a fraud investigation. ExxonMobil has countersued against Healey, arguing she lacks jurisdiction in the matter.

As I indicated above, there are environmentalists who were not impressed by the appointment of a climate scientist to the fossil fuel giant’s board. AFP quotes Shanna Cleveland of Ceres, a nonprofit group that works on shareholder actions to pressure companies to address climate change. She called the move a “really good first step, but not much more than that”, and fears Susan Avery could be a “lone vote in the wilderness” on climate change given ExxonMobil’s record on the issue.

The climate advocacy group 350.org dismissed the appointment as “little more than a PR stunt.”

Scientists to the fore

But at a time when some critics say the Trump administration is threatening environmental democracy in the USA, I would prefer to see Dr. Avery’s new position as a move in the right direction, if a tiny one.

With scientists gearing up to march on Washington in the not-too-distant future, we can do with experts who acknowledge, understand and call for action on climate change on every level, in every corner.

Susan Avery described her time on the UN scientific advisory board in her interview with me here in Bonn as as “a fun exercise.” In the current climate, I cannot imagine the same will apply to being the climate advocate on the board of a controversial fossil fuels giant like ExxonMobil.

Hot, hot, hotter.. can UN talks in Bonn make a difference?

After all the hype surrounding the Paris Climate Agreement in December, there is a real danger of anti-climax, of feeling self-satisfied, of sitting back saying, “Yes, we did”, while the planet continues to break all temperature records and fossil fuel emissions continue to rise.

The first four months of this year were the hottest ever recorded. Even the “ice island” of Greenland has seen temperatures spiking in April, typically a cold month. NOAA says 2016 could be off to a similar start to 2012, when the surface of the ice sheet started melting early and then experienced the most extensive melting since the start of the satellite record in 1978. We have had several reports of islands being submerged by rising seas and devastating forest fires in Canada and now Russia, which experts say will be more common as the planet warms.

Close to my office here in Bonn, Germany’s UN city, the first official working meeting of all the parties to the Paris Agreement started on Monday, going on until next Friday. I have been there, on and off, talking to people, listening in, trying to get a sense of what is happening – or not, as the case may be.

But the atmosphere in Bonn’s new World Conference Centre is definitely low-key compared with the hype surrounding the Paris Climate Conference. Yet the world climate agreement will be worthless if the countries of the world do not succeed in transmitting it into actions in the very near future.

Time to deliver

The President of the Paris COP21, French Environmenent Minister Segolene Royal, and the incoming President of COP22, which will be held in Marrakech, Morocco’s Foreign Minister Salaheddine Mezouar, have made it clear that it is time to shift the focus from negotiation to implementation and rapid action.

The challenge ahead, they say, is to “operationalize the Paris Agreement: to turn intended nationally determined contributions into public policies and investment plans for mitigation and adaptation and to deliver on our promises.”

Indeed. There is no lack of evidence to support the urgent need for faster action on climate change. An increasing number of extreme weather events are being attributed to climate change. The CO2 concentration in the atmosphere is climbing steadily and is likely to cross the critical 400 ppm mark permanently in the not-too-distant future. The global temperature is already one degree Celsius higher than it was at the onset of industrialization. That means very rapid action is needed to keep it to the agreed target of limiting warming to two degrees and preferably keeping it below 1.5 degrees.

Three degrees and more?

The Paris Agreement was hailed widely as a breakthrough, with all parties finally accepting the need to combat climate change by reducing emissions of greenhouse gases. Countries have put pledges on the table, outlining their emissions reduction targets. But so far, the reductions pledged would still take the world closer to a three-degree rise in temperature.

At the Bonn meeting, the International Energy Agency (IEA), issued a warning that governments can only reach their climate goals if they drastically accelerate climate action and make full use of existing technologies and policies.

“The ambition to peak greenhouse gas emissions very soon is anchored in the Paris agreement, but we don’t see the actions right now to make this happen”, said Takashi Hattori, Head of the IEA’s Environment and Climate Change Unit. “At the same time, there are ‘GDP-neutral’ ways and means to get emissions to peak and then fall whilst maintaining economic growth, and that’s what we need to focus on.”

GDP-neutral means that a technology or policy does not negatively impact the economic growth of a country, and can actually contribute to the growth of that country.

In Bonn, Hattori presented what the IEA calls a “bridge scenario” involving the use of five technologies and policies which it says can bridge the gap between what has been pledged by governments so far and what is required to keep the global average temperature to as low as 1.5 degrees Celsius as part of what the agency terms a “well below 2 degrees world”

The five key measures which the IEA say could achieve a peak in emissions around 2020 are energy efficiency, reducing inefficient coal, renewables investment, methane reductions and fossil-fuel subsidy reform. That sounds to me like a very sensible – and practicable set of measures. But that doesn’t mean it will be easy.

Takashi Hattori stressed that “one size does not fit all” when it comes to climate and energy policies. Different measures will be required in different parts of the world. In the Middle East, for example, the greatest potential to reduce emissions is through reducing fossil fuel subsidies, he argued, while energy efficiency would have the greatest potential in Europe and China. He recommended the “massive deployment of renewables” in India and Latin America.

Other solutions outlined include smart grids, hydrogen as fuel that can be generated with renewable sources of energy, and “smart” agriculture.

The IEA says governments should make the energy transition not only because of rising temperatures, but because of other benefits, such as a reduction of air pollution. That makes sense. People in congested cities are more worried about pollution damaging their health than about climate change, the experts say.

I am reminded of an interview I conducted recently with Chinese expert Lina Li, when she told me she thought China’s air pollution problem would speed up the country’s ratification and implementation of the Paris Agreement.

Lina Li from the Adelphi think-tank told me pollution concerns could speed up China’s climate action (Pic. I.Quaile)

The cost argument

Although many scientists are alarmed at the slow pace of emissions reductions, IPCC chief scientist Hoesung Lee told the Guardian in an interview it was still possible to keep to the two-degree target. The current UN climate chief Christina Figueres, who will hand over to Mexican Patricia Espinosa later this year, has said emissions would have to peak by 2020 if that limit is to be kept to. But Lee is keen to keep the options open, saying it would still be possible to keep to the limits if emissions peaked later. But he warned the costs could be “phenomenal”. He believes expensive and controversial geoengineering methods may be necessary to withdraw CO2 from the atmosphere and store it.

A report published this week by UNEP says the cost for assisting developing countries to adapt to climate change could reach up to 500 billion dollars annually by 2050. This is five times higher than previous estimates, the report says.

UNEP urged countries to channel more funds towards adaptation, saying the costs would rise “sharply”, even if countries succeed in limiting global temperature increase to two degrees Celsius.

I asked Mattias Söderberg, Co-Chair of the Climate change advisory group with the climate justice ACT alliance, how he felt about the progress of climate action and the role of the current Bonn meeting. He said the UNEP report, along with the alarming news about islands disappearing under rising seas in the Pacific, highlighted the urgent need for action. “Climate change is not a matter of tomorrow, but a crisis we need to deal with today.”

Time to ratify!

So far, 177 parties have signed the Agreement. But only 16 parties have ratified the treaty. It must be ratified by 55 parties representing 55 percent of total global emissions to enter into force. Söderberg called on wealthy, industrialized countries to move ahead with ratification:

“I am happy to see many of the poor and vulnerable countries moving fast with their ratification, and I hope other countries will follow soon. I am worried about the EU, which seems to be delayed”. Söderberg says the EU, could find itself on the sidelines, overtaken by others.

But the increasing concern over refugees and migration here in Europe could make a lot of countries look more closely at climate change, which is likely to increase the number of people having to leave their homes and look for a better life elsewhere.

“Go, world, go!”

NGO representatives stress that the Bonn talks can only help kick off the series of measures necessary to halt global climate change. Greenpeace climate policy chief Martin Kaiser told me the main work had to be done in the countries themselves, which have to work out their timetables to reach the goals agreed in Paris. That means an early transition to a fossil-free future. Kaiser called on host country Germany in particular, often cited as a model for its shift to renewable energy, to come up with a binding exit strategy for coal by 2030.

“Without an exit from coal, Germany’s signature under the Paris Agreement is worthless”, he told me.

The world’s top emitters, the USA and China, will also have to take major steps to halt climate warming. The delegates meeting in Bonn until May 26 have their work cut out for them. I have always been skeptical about the mass jubilation over the Paris Agreement. Yes, we needed it. But the proof of every pudding is in the eating. All the indications are that 2016 will be the hottest year on record, and probably by the largest margin ever. If the Paris document is to be more than a lot of pieces of paper, we will have to see things happening very soon – and definitely not just in the conference rooms of Bonn and elsewhere.

Earth Day, Climate pact signing – and the Arctic?

How are you feeling this Earth Day? In some ways it could mark a turning point for the planet, with some 165 countries signing the Paris climate treaty at UN headquarters in New York. But, as, always, the proof of the pudding will be in the eating. And so far, I’m not sure it is quite tasty enough.

The trouble is, signing agreements alone is not enough. They have to be turned into action. The world is heating up way too fast, and the transition to an emissions-free world is far too slow. Yes, we can do it, I am convinced. But as well as the political will to sign an agreement, we need the political will to implement measures which will be unpopular with businesses and consumers because they mean major changes to how we work, trade and live.

In the meantime, the Arctic is facing a decline in sea ice that could equal or even beat the negative record of 2012.

Sea ice physicists from the Alfred Wegener Institute, Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research (AWI), have evaluated current satellite data on the thickness of the ice cover. The data show that the Arctic sea ice was already extraordinarily thin in the summer of 2015 and comparably little new ice formed during the past winter. Speaking at the annual General Assembly of the European Geosciences Union in Vienna, AWI sea ice physicist Marcel Nicolaus said data collected by the CryoSat-2 satellite revealed large amounts of thin ice that are unlikely to survive the summer.

Hard to forecast

Predicting the summer extent of the Arctic sea ice several months in advance still poses a major challenge to scientists and meteorologists. Between now and the end of the melting season, the fate of the ice will ultimately be determined by the wind conditions and air and water temperatures during the summer months. However, conditions during the preceding winter lay the foundations.The AWI scientists say this spring, conditions are as “disheartening as they were in 2012”, when the sea ice surface of the Arctic went on to reach a record low of 3.4 million square kilometres.

At the end of March, the Arctic sea ice was at a record low winter maximum extent for the second straight year, according to scientists at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) and NASA. Air temperatures over the Arctic Ocean for the months of December, January and February were 2 to 6 degrees Celsius (4 to 11 degrees Fahrenheit) above average in nearly every region.

This year’s maximum winter extent was 1.12 million square kilometers (431,000 square miles) below the 1981 to 2010 average of 15.64 million square kilometers (6.04 million square miles) and 13,000 square kilometers (5,000 square miles) below the previous lowest maximum that occurred last year.

The September Arctic minimum began drawing attention in 2005 when it first shrank to a record low extent over the period of satellite observations. It broke the record again in 2007, and then again in 2012. The March Arctic maximum tended to attract less attention until last year, when it was the lowest ever recorded by satellite.

Ice conditions “catastrophic”

Recently, here on the Ice Blog, I published an account by Larissa Beumer, one of a team of Arctic experts on board the Greenpeace ship the Arctic Sunrise, which has been checking the ice conditions the Arctic archipelago of Spitsbergen. From the ship, she told me the ice conditions were “catastrophic and way outside of normal variations”. She reported transport problems, with many of the usual routes inaccessible by dog sled or snow mobile. She talked of a lack of ice in places where navigation is usually impossibly up to June or July.

Ice and open water, photographed by Nick Cobbing for Greenpeace, from the Arctic Sunrise, off Spitsbergen.

On thin ice

AWI scientist Marcel Nicolaus says new ice only formed very slowly in many regions of the Arctic, on account of the particularly warm winter.

“If we compare the ice thickness map of the previous winter with that of 2012, we can see that the current ice conditions are similar to those of the spring of 2012 – in some places, the ice is even thinner,” he told journalists at the Vienna Geosciences meeting.

Nicolaus and his colleague Stefan Hendricks evaluated the sea ice thickness measurements taken over the past five winters by the CryoSat-2 satellite for their sea ice projection. They also used data from seven autonomous snow buoys, which they placed on ice floes last autumn. These measure the thickness of the snow cover on top of the sea ice, the air temperature and air pressure. A comparison of their temperature data with AWI long-term measurements taken on Spitsbergen has shown that the temperature in the central Arctic in February 2016 exceeded average temperatures by up to 8 °Celsius.

Breaking ice record

In previously ice-rich areas like the Beaufort Gyre off the Alaskan coast or the region south of Spitsbergen, the sea ice is considerably thinner now than it normally is during the spring. “While the landfast ice north of Alaska usually has a thickness of 1.5 metres, our US colleagues are currently reporting measurements of less than one metre. Such thin ice will not survive the summer sun for long,” Stefan Hendricks said.

The scientists say all the available evidence suggests that the overall volume of the Arctic sea ice will be decreasing considerably over the course of the coming summer. They suspect the extent of the ice loss could be great enough to undo all growth recorded over the relatively cold winters of 2013 and 2014. “If the weather conditions turn out to be unfavourable, we might even be facing a new record low,” Stefan Hendricks said.

So the AWI researchers fear we are going to see a continuation of the dramatic decline of the Arctic sea ice throughout 2016. From that point of view, the signing of Paris climate pact comes way too late. UN Secretary-General Ban ki-Moon is stressing that this can only be the beginning, and that the mammoth task of decarbonising the economy still lies ahead. Here’s hoping the Paris Agreement will not just be a piece of paper which governments use to salve their consciences. Here in Germany, people are concerned that the government will not reach its ambitious climate targets at the present pace. Given that this country has already made remarkable progress in the transition to renewable energy for its electricity production, that is a worrying trend. And other major emitters still have even more to do if that two degree, let alone the 1.5 degrees Celsius limit to global warming is to be more than a very hot piece of pie in the steadily warming sky.

Feedback