Search Results for Tag: glaciers

Greenland’s icecap losing stability

Catching up on the last few weeks of icy news after a spring holiday, my eye was caught by an item by Tim Radford from the Climate News Network, dated April 13th. I quote: “Greenland is losing ice from part of its territory at an accelerating rate, suggesting that the edges of the entire ice cap may be unstable”. This caught my attention not just because anything relating to Greenland tends to do that, but because the development could have major significance for the future world climate and sea level- and because it doesn’t seem to have made its way into the mainstream media at a time when sensitivity to the issue should have been high after the IPCC report.

The Greenland ice sheet is the largest terrestrial ice mass in the northern hemisphere. Radford draws attention to a study in Nature Climate Change by Shfaqat Khan from the Technical University of Denmark and colleagues, which indicates that the ice sheet could be melting faster than previously thought. This would mean Greenland’s contribution to sea level rise has been under-estimated (once again!), and oceanographers may need to think again about their projections.

The scientists used more than 30 years of surface elevation measurements of the entire ice sheet to discover that overall loss is accelerating. Previous studies had identified melting of glaciers in the island’s south-east and north-west, but the assumption had been that the ice sheet to the north-east was stable, Radford writes:

“It was stable, at least until about 2003. Then higher air temperatures set up the process of so-called dynamic thinning. Ice sheets melt every Arctic summer, under the impact of extended sunshine, but the slush on the glaciers tends to freeze again with the return of the cold and the dark, and since under historic conditions glaciers move at the proverbial glacial pace, the loss of ice is normally very slow.”

But with global warming, Greenland’s southerly glaciers have been in retreat and one of them, Jakobshavn Isbrae or Sermeq Kujalleq, is now flowing four times faster than it did in 1997. I first reported on this during a trip to Greenland in 2010, and have presented various new studies on it here on the Ice Blog since.

The new research by the Danish-led team considers changes linked to the 600 kilometre-long Zachariae ice stream in the north-east, using satellite measurements. It has retreated by some 20 kilometres in the last DECADE, whereas Sermeq Kujalleq has retreated about 35 kms in 150 years. The Zachariae stream drains around one-sixth of the Greenland ice sheet, and because warmer summers have meant significantly less sea ice in recent years, icebergs have more easily broken off and floated away, which means that the ice stream can move faster. “North-east Greenland is very cold. It used to be considered the last stable part of the Greenland ice sheet,” said one of the team, Michael Bevis of Ohio State University in the US, in an interview with the Climate News Network.

“This study shows that ice loss in the north-east is now accelerating. So now it seems that all of the margins of the Greenland ice sheet are unstable.”

The scientists used a GPS network to calculate the loss of ice. Glacial ice presses down on the bedrock below it: when the ice melts, the bedrock rises in response to the drop in pressure, and sophisticated satellite measurements help scientists put a figure on the loss of ice. They calculate that between April 2003 and April 2012, the region was losing ice at the rate of 10 billion tons a year.

“This implies that changes at the margin can affect the mass balance deep in the centre of the ice sheet,” said Dr Khan. Sea levels are creeping up at the rate of 3.2 mm a year. Until now, Greenland had been thought to contribute about half a mm. The real figure may be significantly higher, according to the report.

This is a very worrying development, but it seems to me it did not get a lot of public attention. This brings me back to the question of the discrepancy between what we know about the impacts of climate change and the widespread lack of political and consumer action. (See my article Denial or Disconnect: Why don’t we act on climate change?)

Are people sticking their heads in the sand (or melting snow)? Have we just been assured so many times that the Greenland ice sheet will never melt that we don’t sit up and take notice? Is it too far away in time and space to bother us? Are too many people giving up and resigning themselves to the fact that climate change is inevitable? Is it just so much easier to hold on to the status quo instead of having to make changes to our 21st century lifestyles?

Greenland glacier at record speed

I have been working on a story about whether the Arctic infrastructure would be able to cope with a shipping or oil spill accident, which is increasingly likely to occur as development speeds ahead. During the Arctic Frontiers conference in Tromso, I attended an interesting workshop on the topic, where the organisers, the Arctic Institute Center for Circumpolar Security Studies, came to what their experts describe as “worrisome” conclusions. Malte Humpert, Kathrin Keil and Marc Jacobsen presented three incident scenarios involving shipping and oil exploration in the Arctic. Jacobsen’s scenario involved a giant cruise boat with 3000 people on board hitting an iceberg off the West Greenland Coast, near Ilulissat.

In 2009 I was in Ilulissat, working on radio features on climate change in Greenland. This is the Greenland of the tourist brochures, with a constantly changing panorama of icebergs floating past your hotel window – or porthole if you are on a ship. While I was there, the fragility of that beautiful glacier ice was brought home to me.

The Sermeq Kujalleq glacier, also still known by its Danish name “Jakobshavn Isbrae”, is the fastest flowing glacier in Greenland (or Antarctica, these two major ice sources being of key importance to global sea level). The icebergs which create the spectacle floating past the brightly coloured houses of Ilulissat, are breaking off from the glacier. Beautiful to look at, extremely worrying if you think about the background. Back in 2009, scientists were already telling me the glacier was speeding up. Now the latest research published in The Cryosphere (the journal of the European Geosciences Union) confirms that the summer flow of the ice mass has reached a record speed. The scientists, from the University of Washington in Seattle and the German Aerospace Center DLR, say the speeding up in 2013 was 30 to 50 percent higher than previous summers. The scientists analysed satellite images taken every 11 days from early 2009 to spring 2013. Satellite technology plays a key role in observing the ice. Two German radar satellites TerraSAR-X und TanDEM-X provide high resolution data that facilitates precise calculations, according to DLR. One of the authors, Dana Floricioiu from the DLR Earth Observation Center in Oberpfaffenhofen, told journalists it had been striking to see how much the glacier was changing within a very short time.

The researchers found that the glacier’s average speed peaked at 46 metres per day during the summer of 2012. This is the fastest ever recorded for a glacier in Greenland or Antarctica. The big surges take place in summer, but the researchers say the average annual speed of the glacier over the last two years is almost three times what was measured in the 1990s. It is retreating by around 17 kilometres per year. The scientists say these speeds were achieved “as the glacier terminus appears to have retreated to the bottom of an over-deepened basin with a depth of around 1300 m below sea level. The terminus is likely to reach the deepest section of the trough within a few decades, after which it could rapidly retreat to the shallower regions some 50 km farther upstream, potentially by the end of this century”.

The huge volume of ice going into the sea from the Sermeq Kujalleq glacier is already influencing sea level. The glacier drains around 6 percent of the massive Greenland ice sheet Scientists estimate it added about 1 millimetre to global sea levels from 2000 to 2010. The increased speed of the discharge will exacerbate this further.Badnews for people in low-lying coastal areas around the globe. And this is not the only Greenland glacier melting increasingly.

Coming back to the subject of disaster-preparedness – this glacier is thought to be the source of the iceberg that sank the Titanic in 1912. The Arctic Institute’s scenario indicates that an accident like the “Costa Concordia”, which happened in an easily accessible region with no ice or dangerous weather conditions, would have devastating consequences if it happened, say, off the coast of Ilulissat. Search and rescue, accommodation and medical treatment, lack of transport facilities, poor communications infrastructure, no adequate oil spill response technology for icy waters…. food for thought for companies looking to profit from the changing climate of the Arctic – and the governments that should be responsible for protecting humans, wildlife and that beautiful but fragile Arctic ecosystem.

Polar ice tipping points

As I get ready to head up to Tromso for the Arctic Frontiers conference and prepare my accreditation for the next routine round of climate talks here in Bonn in March, I find myself with plenty of food for thought.

It seems like not that long ago that scientists were telling us that although the Arctic is clearly melting fast, there was no need to worry about the Antarctic ice melting. But for the past 15 years or so, scientists have been observing that glaciers in West Antarctica are out of balance. Ice shelves have been breaking off and the calving fronts of glaciers have been retreating, draining huge amounts of ice into the ocean. This week I was interested and concerned to read about the results of a modelling effort, using 3 different types of model, indicating a key Antarctic glacier was melting irreversibly.

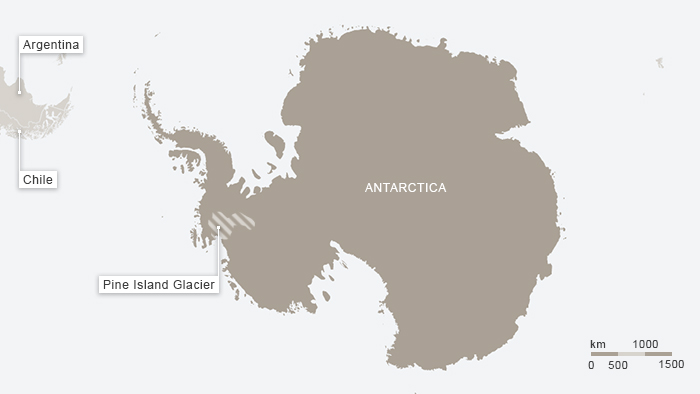

(Map courtesy of Deutsche Welle)

The Pine Island Glacier in the Antarctic hit the headlines last year when a giant iceberg broke off it. It is a key glacier because it is actually responsible for some 20 percent of the total ice loss from the region. Now scientists have found the glacier is melting irreversibly – with dramatic consequences for global sea levels. For an article for DW entitled Antarctic’s glacier retreat unstoppable, I interviewed Gael Durand of the French University of Grenoble, one of a team of scientists who have just published the new study: “We show that the Pine Island Glacier will continue to retreat and that this retreat is self-sustaining. That means it is no longer dictated by changes in the ocean or the atmosphere, but is an internal, dynamic process”, Durand told me. This will mean an increasing discharge of ice and a greater contribution to global sea level rise. “It was estimated at around 20 gigatons per year during the last decade, and that will probably increase by a factor of three or five in the coming decade. That means this glacier alone should contribute to the sea level by 3.5 to 10 millimetres a year, accumulating to up to one centimetre sea rise over the next 20 years. For one glacier, that is colossal”, says Durand.

I called up Angelika Humbert from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute for Polar and Marine Research (AWI) to get an expert opinion on the significance of the new research. She told me 1cm over 20 years would be an “extremely high” amount. The glaciologist, who is also working on models for the Pine Island Glacier, stresses that all models include a degree of abstraction and uncertainty. However, her work also indicates that the glacier will make an increasing contribution to sea level rise in the coming years and describes the new study as a “considerable advance on the results of research to date.” Humbert says the results could well be applied to other glaciers of the same type.

Angelika Humbert from AWI took this picture flying over the Pine Island Glacier in a NASA DC8 as part of the IceBridge campaign in 2011

Durand’s new study shows that the glacier is now flowing at a rate and in a way that makes the process irreversible. Even if the air and ocean temperatures cooled off to what they were a hundred years ago – which is in no way likely – Durand is convinced the glacier would not recover. Durand says the study should arouse concern because the glacier has passed a “tipping point”, a much discussed concept in climate science. “That means because of our behaviour, our climate is changing and will continue to change a lot. I think it is one of the first times we are passing these tipping points.”

The scientist compares the situation to that of a cyclist coming down from the top of a mountain and unable to brake: “We have to fear that the retreat will continue, that other glaciers in the region will start to do the same, and that we will have a collapse of this part of the ice shelf. That would take centuries, but it would mean a rise of several metres in sea level.”

The last report by the Intergovernmental Panel on climate Change (IPCC) warned of the implications if the glaciers of West Antarctica were to become unstable. “Here,” says Durand, “we have proof that that is already happening with this one.”

At the Arctic Frontiers conference two years back, I heard a lot of interesting discussions about climate tipping points. Professor Carlos Duarte Directorof the Oceans Institute at The University of Western Australia and Research Professor with the Spanish National Research Council (CSIC) talked to me at length about tipping points. Let me quote him briefly:

“Tipping Points – or thresholds – are levels of pressures beyond which small response of a property of interest becomes abrupt. Once a system or ecosystem or earth system crosses beyond a threshold, the changes, e.g. in the extent of ice or rate of warming, accelerate greatly, and once the threshold is crossed, it is sometimes very difficult to return to the original state even if pressure is released or reduced.”

We discussed the possible tipping points and warning signs outlined in a key piece of research by Timothy Lenton and others. Some would argue that tipping points have already been crossed in the Arctic region, which is known to be warming at least twice as fast as the rest of the earth. One of Lenton’s other key factors is the West Antarctic ice sheet becoming unstable. Now the “eternal ice” down south could be reaching a kind of “tipping point” in places. Yes, I know this only applies to a particular region of the West Antarctic, but the implications of irreversible glacier melt there are already huge. Greenland and that West Anarctic ice sheet play a key role in storing masses of fresh water, which would have huge implications if they melted. With marine glaciers, like the Pine Island Glaciers, the melt of white ice to expose more dark ocean surface underneath would further increase warming by absorbing solar heat instead of reflecting it back.

With the EU in the news today for considering moving away from binding climate targets, and little progress in sight towards an effective new climate agreement scheduled to be agreed in Paris in 2015, this all puts me in a pensive mood, as I get ready to head north and focus on the implications of the changing climate for “Humans in the Arctic”.

Ice Blog back online!

Apologies for the absence of icy news on the blog over the past three months. I was collecting new stories and pictures of glacier development in the Swiss Alps during a hiking holiday and unfortunately slipped on some ice. It has taken me three months to recover, but before that I did take plenty of pictures, some of which will be appearing on the blog at some point in the next few weeks. I first visited that particular area in 1984, so have photos as well as memories of the glaciers as they looked then, and now. A comparison shows major changes. Many areas which were then iced over are now completely ice free.

In the meantime, of course, there has been no shortage of news and stories in the world at large relating to the polar regions and climate, including the annual sea-ice minimum measurements and the IPCC report.

As for the sea-ice measurements, the scientists from Germany’s Alfred Wegener Institute say the fact that the sea ice covered a bigger area than last year does not mean the ice pack is recovering. Its extent is still very low compared to the long-term average, and is in line with an overall trend towards less of the stable, thicker multi-year ice. A new study published this week suggests the Arctic will be ice-free in summer within 25 years. See this summary and context from the Climate News Network: Ocean damage is worse than thought.

The IPCC report includes a lot more data on developments at the poles, which was lacking in the last report. Ice melt from the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets are shown to be playing a much greater role in increasing sea levels than previously thought. There’s a brief summarizing article on the DW environment page.

More on the “state of the ice” in the coming week. Please look out for regular posts from your Ice Blogger again from now on. It’s great to be back in action.

Earth Hour, Vancouver and the Arctic

WWF has named the City of Vancouver in Canada as the first ever “Global Earth Hour Capital“. The city was awarded the distinction for its “innovative actions on climate change and dedication to create a sustainable, pleasant urban environment for current and future residents.” It is encouraging to see a Canadian city getting this climate award at a time when Canada is about to take over leadership of the Arctic Council and appears to be pushing hard for the economic development of the Arctic region. At the same time, the country’s glaciers are melting fast.

WWF writes:” Vancouver has been recognised by the jury for its ambition to be global leader on climate-smart urban development in spite of low national ambitions.” Those ambitions refer to the Canadian government’s lack of commitment to binding climate protection targets.

Well done to the City of Vancouver for making its own efforts to promote climate action and to reduce its carbon footprint. The activities include making new buildings carbon-neutral, encouraging people to make more than half their trips on foot, on their bicycles or by public transport. The city also wants to double the number of green jobs.

![]() read more

read more

Feedback