Search Results for Tag: ice

Ice paradoxes from pole to pole

Returning after a longish break with little access to news and data, there are several ice and snow stories jumping out of my mailbox at me. I’ve picked out two which those of a skeptical persuasion might say disprove some key climate assumptions, but which actually, in fact, confirm some trends and predictions.

Worrying, but not unexpected, are the latest measurements of the extent of the Arctic sea ice. In February, the experts at the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC) based in Boulder, Colorado, noted a record for the lowest observed maximum sea ice extent. Although it seems the sea ice did grow at some points during March, the overall for the month was the lowest recorded since satellite measurements began in 1979. The average extent for the month was 14.39 million square km – some 1.13 million square km below the 1981-2010 long-term average. The previous March low of 14.45 million square km was recorded in 2006.

In the Arctic Journal, Kevin McGwin quotes Andy Mahoney, a geophycisist with the Sea Ice Group at the University of Alaska Fairbanks, as saying the irregular pattern, with a kind of “double dip”, with the ice decreasing, increasing, then decreasing again, is “a pretty unusual event, regardless of the reason”. Normally, the ice levels would increase to the seasonal maximum first in March, then decline.

One reason, Mahoney says, could be the wind blowing ice into the regions where ice growth was observed, according to the NDSIC the Bering Sea, Davis Strait and around Labrador.

No contradiction to climate warming theory

The NSDIC says warm conditions in the Bering Sea and the Russian Sea of Okhotsk contributed to the record low winter ice maximum.

The overall downward trajectory, however, is clear. The brief increase in March is not a sign that the sea ice is recovering. Mahoney told the Arctic Journal parts of Alaska had seen abnormally high temperatures this winter, which was in line with the overall seasonal ice observations.

“What drives the maximum extent is what happens at the margins, and they can grow and retreat due to short-term variants. The conditions in the central Arctic, far from the action, are indicative of the warm year we’ve had in Alaska,” he said. Barrow, on Alaska’s northern coast, far away from the southern margin, for example, saw a lot of broken ice this winter, according to Maloney.

WWF expressed concerned about the latest figures:

“This is not a record to be proud of. Low sea ice can create a series of reactions that further threaten the Arctic and the rest of the globe,” said Alexander Shestakov, Director, WWF Global Arctic Programme.

“This chilling news from the Arctic should be a wakeup call for all of us,” said Samantha Smith, the leader of WWF’s Global Climate and Energy Initiative. She stresses the need to cut global emissions to halt the Arctic melt.

The proportion of thick Arctic ice that lasts multiple years has dwindled over the past two decades. A recent study shows that Arctic sea ice has thinned by 65 per cent since 1975, leaving ice that is more susceptible to melting.

Writing for Alaska Dispatch News (AND), Yereth Rosen notes that the most dramatic changes in the Arctic sea ice extent have been in the melt season, not in the period of maximum winter coverage. He quotes NSIDC scientist Julienne Strove, who led a study published last year in Geophysical Research Letters which showed the open-water season is lengthening, mostly because of extended melt in summer and autumn. So is this additional winter record a sign of more melting to come? Only time will tell, but the signs are not looking good.

Warmer temperatures, more snow? Belgian International Polar Foundation shot of director and explorer Alain Hubert in the Antarctic.

A story from the opposite pole has also attracted attention. It says climate change is actually increasing the amount of snow in the Antarctic. Puzzling? Not necessarily.

More heat, more snow?

An international study headed by Germany’s Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact research (PIK) comes to the conclusion that every degree of regional warming could increase snowfall there by around five percent. The estimate is based on ice cores and climate modeling.

The information adds a new element to calculations of how much the Antarctic will contribute to global sea level rise. Some people might assume more snow would stop the Antarctic from losing mass. In fact the increasing weight of new snow and ice can make it slide towards the coast and into the ocean faster. In this connection, you might like to read some more stories on these Antarctic issues:

Thicker-ice-in-the-antarctic-good-news-for-the-climate?

Antarctic melt could raise sea levels faster

West Antarctic ice sheet collapse unstoppable

Anders Levermann, one of the new study authors, whom I have spoken to several times on the effects of climate change on the Antarctic and global sea levels, says the latest results back up earlier conclusions that the Antarctic will lose more ice than it will gain and thus have a major influence on global sea level. Levermann, from PIK, is also one of the lead authors of the sea-level chapter of the IPCC report. He stresses that the latest study just provides yet another piece of the “jigsaw puzzle” coming together on how global sea level is likely to develop in the future.

If the world leaders called on to come up with a new world climate agreement at the end of this year need any more motivation, this scientific research from both ends of the world should really give them an extra push.

Arctic Winter Impressions

Your Iceblogger is off on a hard-earned break for the next few weeks. I’d like to leave you with some photographic impressions of my winter trip to the Arctic. Thanks again to Norway’s Arctic University in Tromso and the organisers of Arctic Frontiers for the opportunity to visit Svalbard and Tromso at this fascinating time of year. Look out for the next post in April, when spring should be well underway.

Ice floats in Kongsfjorden, Svalbard

Svalbard twilight

- Icicles on the nets aboard the Helmer Hanssen

Winter light outside Tromso

Norway’s Polar Satellite Centre

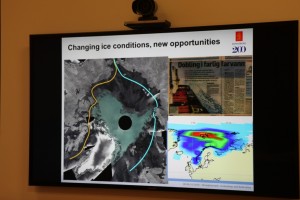

Polar orbit satellites monitor what’s happening at the ends of the planet – and, of course, the regions in between. Ice conditions, land movement, shipping, pollution – but how does that information actually make its way to the scientists and authorities who evaluate it and use it as a basis for all kinds of decisions?

During my recent visit to Arctic Norway, I had the chance to visit a facility that plays a key role in collecting and disseminating satellite data on the polar regions. On the outskirts of Tromso, Norway’s “Gateway to the Arctic”, there is a satellite ground station, run by KSat, or Kongsberg Satellite Services AS. It is a Norwegian commercial company which provides ground station and earth observation services for polar orbiting satellites. With three interconnected polar ground stations: Tromsø at 69°N, Svalbard (SvalSat) at 78°N and Antarctic TrollSat Station at 72°S, combined with a mid-latitude network of stations in South Africa, Dubai, Singapore and Mauritius, KSAT operates over 70 antennae positioned for access to polar and geostationary orbits.

The Tromso station has contact to 85 satellites every day, and every month the station monitors some 15,000 passes of these satellites overhead.

High demand for high-tech service

High demand for high-tech service

When it comes to which businesses stand to gain from climate change, the providers of satellite data have to rank high on the list. There is a huge demand for data from space, and KSat, it seems, is the biggest company worldwide carrying out this kind of activity.

While I was in town for the Arctic Frontiers conference, two colleagues and I were shown the facility on a beautiful wintry Saturday morning by Jan Petter Pedersen, the Vice President of the company, who is responsible for developing products to expand the business. He studied physics in Tromso and got into satellites during that time, he told us, going on to a PHD in remote sensing. Pedersen has been at KSat for 20 years and says the technology has come a long way in that time. These days, it’s all about remote control via pcs.

We tend to take satellite data for granted. But if you think about it, somebody has to pick up the masses of data from all those satellites circling over the poles and pass the appropriate images to those who need them. Energy, environment, security – these are key areas which make use of the data. In the Tromso station, that data is provided to those who need it more or less in real-time. The company says it can get the data down and sent on to its destination anywhere in the world within 20 minutes. So if you want to detect an oil spill in – say – the Gulf of Mexico? – The chances are, you will get information from this Arctic town.

Some companies own and operate their own satellites, and distribute the data. KSat doesn’t own any satellites, but has agreements to use data. They can access radio data from almost all satellites in operation today.

The USA and Canada are the biggest market for the company’s services, says Pedersen. Then comes Europe, followed by Asia.

The world’s largest polar ground station is the one on the Arctic island of Svalbard. I wasn’t able to visit it during my winter trip – put it must be pretty impressive, with more than 30 antennae.

Satellite monitoring as deterrent to polluters?

When it comes to oil spill detection or monitoring, satellite images play a key role.

Optical sensors have limitations in bad weather, so radar satellite data are of key importance, Pedersen explains. Oil spill detection is the most important of KSat’s earth observation activities. EMSO (European marine Safety Agency) in Lisbon is responsible for European oil spill detection. They get satellite data from 4 providers of satellite data, of which KSat is the biggest. It covers 60% of the waters from the Barents Sea to the Bay of Biscay and the Baltic.

In 2008 there were 10.77 possible reported spills per million km2. In 2011, this was down to 5.08, Pedersen told us. I asked why they talk of “possible”. It seems it is not always possible to be 100 percent sure what the satellite detects is an oil spill. The reliability is somewhere over 60 percent. Pedersen believes the satellite service plays a role in decreasing the figure. As it becomes increasingly well known that satellites are observing and collecting the data, there is a higher awareness that oil spills are being detected. Presumably this is a deterrent to deliberate discharges of oil as well as a key source of information on accidents.

From pirates to icebergs

Another key use for satellite data is in monitoring ship traffic, including detecting, tracking and identifying vessels. This means the authorities can spot illegal activities and inform the coast guards. This helps in finding pirates, for instance.

Tracking icebergs and monitoring ice development have also been aided by the growing availability of satellite data. The NSIDC is one of KSat’s most important customers. They need the data to map the extent and condition of the ice.

Satellite data shows ice changes.

Ships frozen into the ice for research purposes such as the Lance, use satellite images via Tromso. Many other ships use them to chart a course when operating in ice.

Monitoring fishing activities, offshore oil exploration, tracking land movement – all these activities rely on satellite information today.

Pedersen told us the Norwegian capital Oslo is sinking at a rate of 2 cm a year. He also mentioned a landslide risk area outside of Tromso, where a mountain is sliding into the ocean. Ultimately, it will go into the fjord and create a tsunami effect, says Pedersen. That would endanger the settlement. It is moving at 15mm per year. The satellites are keeping an electronic eye on it.

Norway, incidentally, is the country with the highest use of data per person. Most of it is maritime. So it seems fitting that the country should be the location of some of the world’s most important ground stations. There is more to the picturesque Arctic harbour town of Tromso than meets the eye – I can tell you that even without satellite data!

Arctic oil – still in the picture

Was it too good to be true? The euphoria over the US administration’s moves to protect the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge was dampened somewhat when, just two days later, it released a long-term plan for opening coastal waters to oil and gas exploration, including areas in the Arctic off Alaska. The plan excludes some important ecological and subsistence areas from potential drilling, but it still includes some Arctic areas, including parts of the Beaufort and Chukchi Seas.

Margaret Williams, managing director of WWF US Arctic Programs, told Deutsche Welle, she welcomed in particular the decision to protect the biological hotspot of Hanna Shoal from risky offshore drilling. The Hanna Shoal is a key site for walruses and other animals.

But she stressed other areas of the US Arctic were still subject to oil exploration. The new program will not affect existing leases held by Shell in the Chukchi Sea. The company’s efforts have been the subject of controversy, not least since the grounding of the drill rig Kulluk.

Williams says the problem with the new proposal in general is that it “keeps drilling for oil in the US Arctic offshore in the picture”. With the US poised to take the helm of the Arctic Council, she called for protecting biodiversity to be a top priority for all Arctic nations.

Oil: valuable asset or liability?

It comes as no surprise that Alaskan state politicians and the oil industry promised to fight planned restrictions, saying they were harmful to the economy. But this brings us back to the question of whether the search for new oil in the Arctic makes any sense at all at a time when oil prices are at a record low and the USA is producing plentiful supplies of shale gas.

Bloomberg financial news group quotes financial experts as saying the world’s biggest oil producers do not have “bulletproof business models”, and cites financial cutbacks by BP, Chevrol and Shell:

“The price collapse hobbles a segment of the industry that had already been struggling with years of soaring construction costs, project delays, missed output targets and depressed returns from refining crude into fuels”, analyst Anish Kapadia told Bloomberg.

Climate paradox

Conservation groups stressed the need for a different focus, in the year when the USA has pledged to help create an effective new world climate agreement in Paris in November.

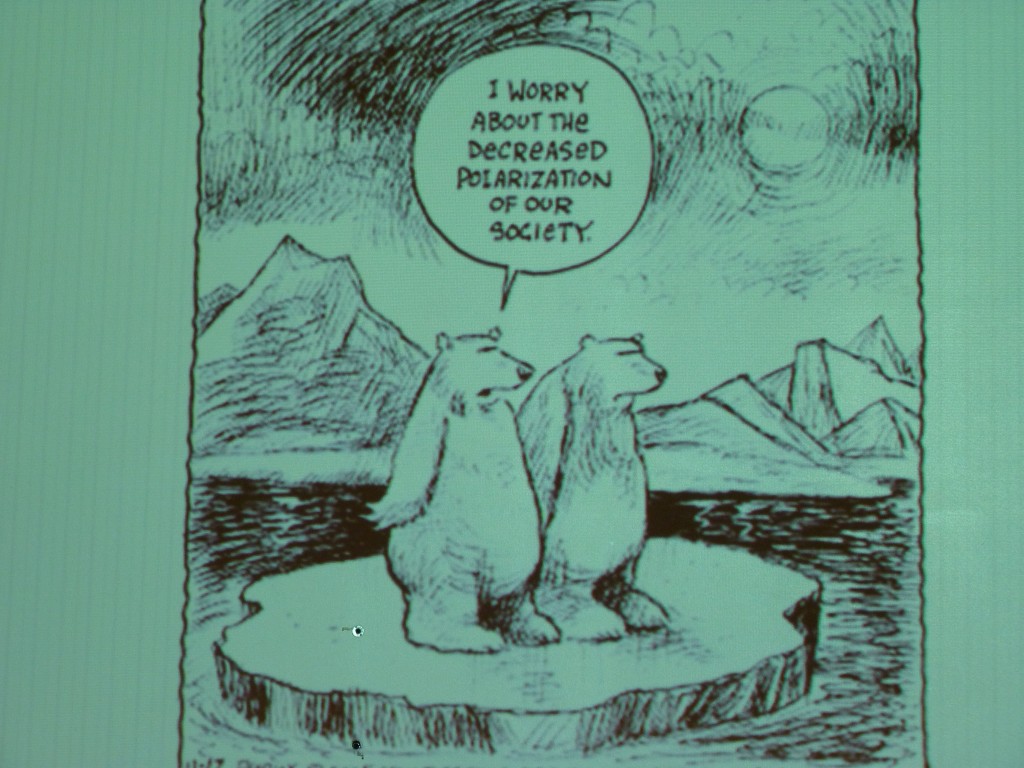

Cartoon by psychologist Per Espen Stoknes, BI Norwegian School of Management.( I photographed it at a workshop on climate change psyschology)

“Rather than opening more of the Arctic and other US coastal waters to drilling for dirty energy, the US needs to ramp-up its transition to a clean energy future. As the Administration works to rally international leaders behind a bold climate pact in 2015, decisions to tap new fossil fuel reserves off our own coasts sends mixed signals about US climate leadership abroad, ” said WWF’s Williams.

We know the Arctic is being hit at least twice as fast as the global average by climate change. The ecosystem is already under huge pressure. The Arctic itself is in turn of key importance to global weather patterns. And burning more oil would exacerbate the situation even further.

“We would like to think that we can shift our energy paradigm to clean energy so that we don’t have to take every last bit of oil out of the earth, especially out of the oceans”, said Jackie Savitz from the Oceana Campaign croup.

Studies by the group and by WWF indicate that developing renewable energy technologies such as offshore wind could create more jobs than hanging on to fossil fuel technologies.

Oil spill concern

In addition to the climate paradox of the hunt for new fossil fuels, environmentalists are concerned about the possible impact of an oil spill. Their opposition is not limited to the Arctic. Proposals to open up large areas of coastal waters including some parts of the Atlantic for the first time have also aroused anxiety about possible pollution. But the Arctic is of particular concern because of its remoteness, harsh weather conditions and seasonal ice cover, which is not likely to disappear soon even with rapid climate change:

“Encouraging further oil exploration in this harsh, unpredictable environment at a time when oil companies have no way of cleaning up spills threatens the health of our oceans and local communities they support. When the Deepwater Horizon spilled 210 million gallons of crude oil five years ago, local wildlife, communities and economies were decimated. We cannot allow that to happen in the Arctic or anywhere else,” said WWF expert Williams.

White House senior counsellor John Podesta justified the ban on oil exploration in the ANWR by saying “unfortunately accidents and spills can still happen, and the environmental impacts can sometimes be felt for many years”. The question is – why should this only be applicable in certain areas? Campaigners say it also applies to the other areas now designated by the administration as “OK” for exploration. For the Arctic in particular, limiting exploration to remote offshore areas does not protect the region against the risk of environmental disaster.

Climate worry grows at Arctic Frontiers

I have followed the past two days, the political section of the Arctic Frontiers conference, with great interest, with the thought of the Paris climate conference in November always at the back of my mind.

Clearly, in a country rich from the sale of oil, cutting climate-killing emissions is a tricky issue. The oil sector was strongly represented here, but so too were those who see the need for a transition away from fossil fuels in the interests of the global climate.

With climate change opening the Arctic to development and the search for the oil, gas and minerals thought to be locked beneath the icy region, this year’s Arctic Frontiers meeting has attracted record participation. The impact of low oil prices on development prospects, and political tensions between Russia and western Arctic states have heightened interest in listening to what experts and decision-makers have to say on the relation between climate and energy.

Arctic fan Prince Albert of Monaco and US special rep Fran Ulmer debated the feasibility of Arctic oil

With prime ministers from Norway and Finland and other ministers from Sweden and Denmark, as well as the US special Representative for the Arctic and the Russian President’s special representative for international polar cooperation addressing the meeting, media interest is high in this Arctic city, two hours flight north of the Norwegian capital, Oslo. (Looking at my flight schedule, I see Oslo is actually closer to Frankfurt than to the Arctic north of the country).

Do we need Arctic oil in a warming world?

The Norwegian premier Erna Solberg was here for the presentation of a report on sustainable growth in the north, a joint venture by Norway, Sweden and Finland. Gas is one of the four drivers named in the report. She left no doubt about her country’s continuing interest in oil and gas exploitation in the Arctic region. She told me in a brief interview she sees no contradiction between this and attempts to reach a new world climate agreement in Paris at the end of the year:

“’We have an oil and gas strategy. There are many not yet found areas where we think there is more gas. We think gas is an important part of a future energy mix, and I think we have to explore to find it.”

The same day, the Norwegian government allocated new licenses for exploration in the north-western Barents sea area of the Arctic. Many of the blocks released for petroleum licensing are close to the sea ice zone that had previously been protected. The zones have now been redefined. Conservation groups are upset. WWF Norway says the announcement is risky, as there is still a lack of knowledge about species and ecosystems in this area.

Will low oil price halt Arctic energy development?

With oil prices at a record low, environmentalists hope Arctic development will slow down or even be put “on ice” permanently. Representatives of WWF told the delegates in Tromso – including high-ranking representatives of major oil companies Statoil and Rosneft – the world does not need oil from the Arctic. And gas should be only a “transition fuel”. Samantha Smith, leader of the ngo’s Global Climate and Energy Initiative, quoted the recent study indicating that 50% of the world’s remaining gas and 30% of the oil must stay in the ground if the two degrees centigrade target for maximum global temperature rise agreed by the international community is to have any chance of being adhered to. She presented an alternative vision of “a thriving green economy in the white north”, with renewable energies replacing the search for oil and gas.

Business rethinking fossil investment?

As I wrote here on the Ice Blog after the Sunday evening opening, it is not only the environment lobby that is advocating a switch to renewable enerergy. Jens Ulltveit-Moe, the CEO of Umoe, one of the largest, privately owned companies in Norway, active amongst other things in shipping and energy, said with the current low oil price, Arctic oil was simply not viable, and this would remain the case for many years to come. And by then, he said, the EU’s climate targets and the international support for a two-degree target would make fossil fuels a non-option.

But Sjell Giæver, Director of Petroarctic and Tim Dodson, Norwegian Statoil’s Head of Global Exploration, insisted short-term price drops alone would not halt Arctic exploration. The region was the last place to discover large new reservoirs to satisfy continuing high demand for oil and gas for an increasing world population.

Oil ventures in the Arctic have not been particularly successful in recent years. Statoil’s Dobson admits the biggest ever exploration drilling programme in the Barents Sea last year had a disappointing outcome. Statoil and others have also withdrawn from the hunt for oil off the coast of Greenland.

Russia hungry for Arctic energy

But the Russian President’s Special Representative for International Cooperation in the Arctic, Arthur Chilingarov, who is also a Member of the Board of Directors at the Russian oil giant Rosneft, stressed the company had completed construction of the northernmost well in the world last September. He said a new oil and gas field has been discovered and the program of Rosneft for 2015 to 2019 provided for a large volume of prospecting and drilling in the western part of the Arctic.

The rector of Tromso UiT Arctic University of Norway Anne Husbeckk and the mayor of Tromso Jens Johan Hyort have reason to be happy with the attendance at this year’s Arctic Frontiers event.

One factor however that is slowing Russian activity the Arctic is the implementation of sanctions by European countries and the USA on account of the tensions over Ukraine. Russia has turned to China and other countries for help, but the lack of western technology is an obstacle to further development in a region where bad weather, ice, remoteness and complete darkness in the winter months make oil and gas development a risky business.

There is a clear tendency amongst those involved in Arctic cooperation to play down the sanctions and keep political tensions out of the region. Norwegian President Solberg told me: “We have a good relationship in the Arctic Council with Russia. We have said we will be in line with Europe on sanctions, although Norway is one of the countries hit most by the counter-sanctions from Russia, for instance the fact that oil and gas exploration are among the sanction areas.”

But in the meantime, on a day-to-day basis, cooperation continues, for instance in the joint management of fish resources, said Solberg.

Business as usual?

While the debate continued in the political section of Arctic Frontiers, a new, business strand of the conference opened in parallel. It focuses – on oil, gas and minerals. Olav Orheim from GRID Arendal, a centre that works with UNEP, stressed that a lot of people here are in favour of Arctic oil and gas exploration, in the interests of jobs and economic benefits.Yet after the publication of last year’s IPCC report and with climate change high on the international agenda, there seems to be a wider acceptance here in Tromso of the disconnect between burning fossil fuels and the ever more urgent need to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

Gunnar Sand is Vice President of SINTEF, the Norwegian “Foundation for Scientific and Industrial Research”, which has close ties to the oil business. From a moral point of view, “we all want to stay below the two degree limit”, says Sand. But it is not possible to change a society and an infrastructure based on fossil fuels overnight.

Technical progress too slow to stop warming

Technology for renewable energy is still not developing fast enough, says Sand. Emission reduction scenarios also rely heavily on carbon capture and storage (CCS), which would reduce emissions from fossil fuel burning and bridge the transition to a low-carbon economy. But the technology, which he himself has been involved in, is moving too slowly. I first met him during a visit to Svalbard, when he told me about a carbon capture and storage project, designed to capture emissions from Longyearbjen’s power station underground. He confirmed in Tromso that it has never been put into action.

Global warming, Sand says, is the most serious challenge of our time. This has to be reflected in political priorities. Governments have to create economic incentives to speed up change.

Salve Dahle, Chairman of the conference steering committee and master of ceremonies sporting a sealskin bow tie.

US special representative ex-Admiral Robert Papp indicated dealing with climate change would be one of the key policy drivers when the USA takes over the Chair of the Arctic Council, the international body that coordinates Arctic affairs, in April.

The Chair of the US Arctic Research Commission Fran Ulmer says a carbon tax would be the best way forward, to encourage industry and consumers to save energy and cut emissions. But she acknowledged the reluctance of governments to impose decisions that could upset their voters at the next election. That is the reality we face as countries weigh up their pledges for the November climate conference in Paris.

Feedback